Epidemiology and Incidence

APSGN is most prevalent in developing countries,

9 and it may occur sporadically or in epidemic form. Although the sporadic form is more common, analysis of epidemics has been particularly revealing.

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25 It affects children more than adults, with peak age from 2 to 6 years (

Table 46.2). Approximately 5% of cases are found among children younger than 2 years, with a slightly greater incidence (5%-10%) in adults older than 40. Spread between family members is common, and nephritogenic streptococci have been isolated from household pets.

26 Males have overt nephritis more commonly, and females tend to have more subclinical disease.

15,

27 Cases of subclinical nephritis outnumber those of overt nephritis (4:1 to 10:1).

2,

28 In temperate zones, APSGN occurs more commonly in winter months, and typically after pharyngitis; whereas in the tropics, skin infections during the summer are the initiating event.

29 Cyclical outbreaks of epidemic forms have been observed, although the reason for these cycles has not been fully explained.

21,

30,

31APSGN follows infection with only certain groups of streptococci, termed “nephritogenic.” Group A streptococci are responsible for the majority of cases, and certain types predominate.

5,

32,

33 Nephritogenic group A streptococci have been characterized serologically by their cell wall proteins, M and T.

5,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40 The risk of nephritis following infection with nephritogenic strains depends on the location of infection. For example, with type-49 streptococci, the risk of nephritis is five times greater with skin infections than with pharyngitis.

Nephritis following pyoderma with types 47, 55, 57, and 60 is also common.

5,

15 The identification of nephritogenic strains suggests that there are factors unique to these

strains that are pathogenically relevant (see later). However, host factors also play a role, as only approximately 10% of patients infected with nephritogenic strains develop overt disease. ASPGN has been reported following renal transplantation, although these patients are at no greater risk for the disease.

41

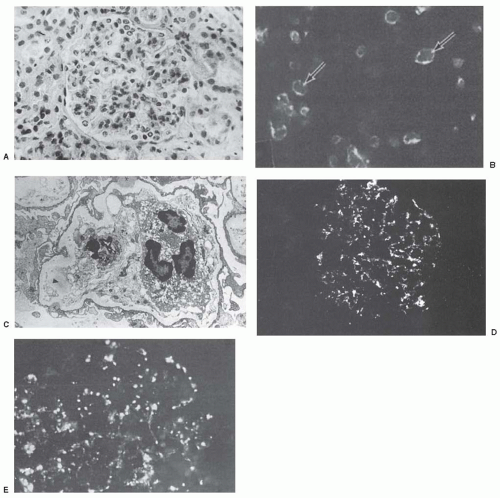

Typically there is diffuse glomerulonephritis, with variable severity.

41,

44,

56,

60,

61,

62 On light microscopy, there is cellular infiltration and glomerular cellular proliferation.

63 The predominant cell types depend on the timing of the biopsy. Within the first 2 weeks of disease, neutrophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes are present in the capillary lumen and in the mesangium, and endothelial and mesangial cell proliferation is prominent.

5,

35,

42 CD4 T cells usually exceed CD8 cells early on, whereas later CD8 cells predominate. Periglomerular accumulation of T cells may also be observed.

45 Occlusion of capillary lumen is not unusual, and mesangial expansion is typical.

44 Intracapillary fibrin thrombi and deposits and/or necrosis are observed in some cases. This pattern characterizes the so-called “exudative phase.” During this period, intermittent thickening of capillary walls, corresponding to large subepithelial immune deposits, or “humps,” are often observed (i.e., by trichrome staining). Focal capsular adhesions or segmental crescents are relatively common. Abundant crescent formation is unusual, but has been seen in more severe situations.

5,

46 Over 4 to 6 weeks, polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) are no longer present, and hypercellularity with mononuclear cells (mesangial cells and/or infiltrating monocytes) predominates. During this latter phase, capillary lumens are usually patent. Glomerular hypercellularity usually slowly resolves, although mesangial hypercellularity may persist for months. Extraglomerular abnormalities are usually not as prominent

during either phase; however, interstitial edema, tubular necrosis, scattered mononuclear interstitial infiltrates, and/or mild arteriolitis have been observed.

48 Severe vasculitis has been reported but is unusual.

49,

50,

51By immunofluorescence microscopy, deposits of immunoglobulin G (IgG) and C3 are distributed in a diffuse granular pattern within the mesangium and capillary walls.

44,

53,

54,

55,

64 C3 is invariably present, whereas the quantity of IgG depends on the timing of the biopsy, and it is not uncommon to see only C3 deposits very early or late in disease. IgM can be present early in disease but may also be observed in smaller amounts later on. Significant amounts of IgA suggest an alternative diagnosis (e.g., IgA nephropathy or Henoch-Schönlein purpura). Clq and C4 are not usually detected; however, properdin and terminal complement components (C5b-9) are often present and in a granular pattern. Fibrin deposits can be detected in more severe cases. Different patterns of immune deposition have been observed, usually related to the timing of the renal biopsy. Early in the disease (the first few weeks), the fine granular appearance of immune deposits resemble a “starry-sky” appearance; this pattern is associated with glomerular hypercellularity.

53,

54,

55 With resolution of the disease (after 4-6 weeks), the immune deposits take on a more mesangial pattern, prior to

disappearing. C3 may be present in the absence of detectable Ig, either very early in the disease (less than 2 weeks) or with disease resolution (i.e., with resolution of the IgG deposits). In about one fourth of cases, the deposits are large, and they aggregate in a rope or garlandlike pattern, and this pattern may be associated with persistent mesangial hypercellularity on light microscopy. When these type deposits are present, they may last for months and be associated with heavy proteinuria and development of glomerulosclerosis.

52,

53,

54,

55 By contrast, transition to a mesangial pattern is usually associated with clinical and pathologic resolution. Immune deposits in small vessels may occur in the setting of vasculitis.

Dome-shaped subepithelial electron-dense Ig deposits, which resemble camel “humps,” are the hallmark feature on electron microscopy.

42 These humps are most abundant within the first month, and frequently observed near epithelial slit pores.

12,

55,

56,

57 They have been associated with heavy proteinuria, and resolve within 4 to 8 weeks. In later stages of the disease, they may be absent; however, remnant electron-lucent areas are occasionally observed and provide diagnostic clues.

58 Subendothelial, mesangial, and intramembranous deposits (along with smaller subepithelial deposits) are often present in variable amounts, and they usually persist after resolution of subepithelial humps.

58 Patients with large subendothelial deposits, without me-sangial deposits, were found to have more proteinuria and edema.

59 Large intramembranous deposits are associated with the garlandlike pattern of immune deposits.

55 The basement membrane is usually of normal diameter, although thickening has occasionally been observed.

48 Cellular infiltration and proliferation relates to the timing of the biopsy, as described.

The symptoms of the disease are characteristic; however, most patients present with only a few features of the

acute nephritic syndrome.88 Typical presentations include edema, gross hematuria, and hypertension.

5,

11,

12,

14,

15,

17,

21,

25,

61,

64,

89 Anasarca is more common among children.

5 Occasionally, patients with gross hematuria will complain of dysuria. Hypertensive encephalopathy is unusual, but if untreated may be associated with seizures.

5,

12 Encephalopathy may occur in the absence of significant hypertension due to cerebral vasculitis.

90 Some patients present with signs and symptoms of congestive heart failure; however, coexistence of rheumatic fever is rare.

15 Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis with acute renal failure is unusual but well documented.

91 Hypertension and heart failure usually resolve after diuresis.

Children are more frequently affected than adults, although diagnosis may be delayed in the elderly.

5,

15,

21,

27,

31 During epidemics, most infected individuals develop only subclinical evidence of nephritis.

27,

29,

61,

92 Nephrotic syndrome occurs in 5% to 10% of children and ˜20% of adults,

5 and may occur either initially or later with improvement in glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis occurs infrequently in children (˜2%), and it is slightly more common in adults. In children, the clinical symptoms of acute glomerulonephritis usually resolve within 1 to 2 weeks; in adults, resolution may be more prolonged with a higher incidence of progressive renal disease.