Chapter 24 Acute Colonic Pseudo-obstruction

Introduction

Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction (ACPO) is a disorder characterized by massive dilation of the colon in the absence of mechanical obstruction. This severe motility disturbance, also known as Ogilvie’s syndrome,1 usually develops in hospitalized patients and is associated with various medical and surgical conditions. The tension on the colon wall resulting from the extreme dilation can lead to ischemic necrosis and perforation, especially in the cecum. The rate of spontaneous perforation has been reported to be 3% to 15% with an attendant 40% to 50% mortality rate.2–5 Despite the potential risk of perforation, approximately 75% of patients with ACPO recover over an average of 3 to 5 days when treated with a variety of conservative measures.3,4 During the sometimes prolonged recovery phase, however, ACPO contributes greatly to patients’ discomfort and immobilization and may delay institution of enteral nutrition.

For the minority (about 25%) of patients who fail to respond to conservative therapy and for patients who have severe, prolonged colonic dilation risking perforation, more active interventions are instituted. In the past, surgical cecostomy and hemicolectomy were the main options in severe or refractory cases. Subsequently, colonoscopy and various radiologic procedures were reported to help decompress the colon.5–10 More recently, medications such as neostigmine have been shown to be effective.11 The timing and combination of conservative and more active interventions must be individualized according to the severity of ACPO and the patient’s comorbidities.

Epidemiology

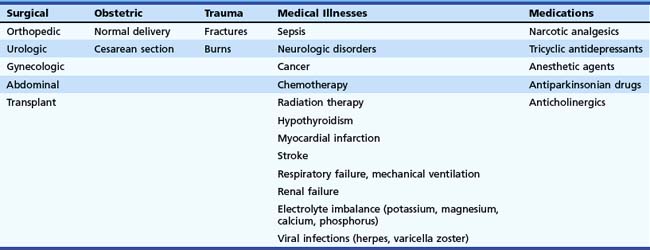

ACPO is relatively uncommon. It can be triggered by various acute medical and surgical illnesses. Typically, rapid-onset abdominal distension begins within a few days of the onset of the underlying illness.2 Because ACPO is uncommon, one must look at reviews that examine several years of reported cases to be able to draw conclusions about the epidemiology of the condition. Numerous case reports and reviews describe specific triggers. However, each proposed underlying condition seems to be associated with the development of ACPO in only a very small percentage of cases. ACPO has been reported after various surgeries, including orthopedic, urologic, gynecologic, neurologic, and organ transplants.3,4,12–21,22 It is seen in obstetrics after vaginal deliveries and cesarean sections.3,23,24 Trauma and burn patients sometimes develop ACPO.3,4,12,25 Various medical illnesses are known to cause ACPO, including sepsis, respiratory failure, mechanical ventilation, renal failure, myocardial infarction, vascular emergencies, sickle cell crisis, and cancer.3,4,12,26–37 Many medications can precipitate ACPO, especially narcotic analgesics and any medication that decreases peristalsis, such as tricyclic antidepressants or anticholinergic drugs.5,7,38–40 Table 24.1 lists these associated conditions. Although the connection between any of these causes and ACPO is most likely through a disturbance in the autonomic innervation of the bowel, other variables, such as patient age; comorbidities; and factors such as immobility, medications, and electrolyte imbalances, are thought to help precipitate the onset in an individual patient.2

In one review of 351 ACPO cases from 1948–1980, 88% followed surgery, trauma, or acute medical illnesses.3 The remaining 12% were classified as idiopathic. This review reported a 15% perforation rate, with a 45% mortality in patients with colonic perforation. This high mortality was attributed in part to the fact that these patients already had serious underlying medical or surgical problems.

In another review of 400 patients from 1970–1985, 95% of the cases had identifiable underlying medical, surgical, or obstetric conditions4; this left only 5% to be categorized as idiopathic. ACPO usually developed within 5 days of onset of the underlying condition. The median patient age was about 60 years, and the male-to-female ratio was 1.5:1. Perforation rate was 20%, and mortality in patients with perforation was about 40%. Overall, mortality in the group was 15%. Mortality rate was affected by age, cecal diameter, length of dilation of colon, presence of ischemia in bowel wall, and patient comorbidities. One important observation in this review was that patients with cecal diameter 8 to 25 cm usually had viable colon without significant ischemia. Cecal size alone is not the only factor in the risk of perforation. Other variables, such as the acuity of the onset and the duration of distention, were also potentially important factors.

Pathogenesis

In 1948, Ogilvie1 first described massive colonic distention in two patients who had the onset of abdominal distention over a few weeks, rather than the more acute presentation that we currently refer to as Ogilvie’s syndrome. Ironically, by today’s criteria, neither would be categorized as ACPO. Both patients were ultimately found to have widespread intraabdominal malignancy with retroperitoneal involvement of nerve plexuses, leading Ogilvie to speculate that disruption of the autonomic innervation of the colon was the underlying cause of the disorder.1

Despite the variety of possible triggers of ACPO, the presentation is remarkably consistent. Generally, patients develop severe abdominal distention within 5 days of the onset of the medical or surgical insult. The intestinal dilation is usually most pronounced in the colon, especially proximal to the splenic flexure. On x-ray examination, the appearance is very similar to that of a patient who actually has an obstruction near the upper left colon, leading to the term pseudo-obstruction. These facts led to the hypothesis that the final common pathway of the development of the disease is an acute cessation of effective colonic motility resulting from a disruption of the autonomic supply of the left side of the colon. One hypothesis was that excess sympathetic stimulation of the colon was inhibiting contraction. This hypothesis seemed to be supported by the observation that this distention occurred in any sort of severe physical stress. In addition, epidural anesthesia to decrease sympathetic output has been reported to be beneficial treatment for ACPO.41 However, when guanethidine was used to block sympathetic tone, there was very little effect on colonic function in ACPO patients.42

The leading current theory about the pathogenesis of ACPO is that a decrease in parasympathetic stimulus to the colon is more important than an excess of sympathetic input.43 In the study of guanethidine mentioned previously, patients first were given guanethidine and then were treated with neostigmine to block acetylcholinesterase. Patients had a prompt return of colonic contraction only after the neostigmine, leading to the idea that a loss of parasympathetic tone is important in the development of ACPO. Some authors speculate that the parasympathetic deficiency is most pronounced in the left colon because of disruption of supply from the sacral plexus; this may explain why the left colon is contracted and aperistaltic in ACPO. Since these pioneering studies, the one medical treatment that has had the most consistent success in treatment of ACPO has been the use of neostigmine to cause a sudden increase in acetylcholine concentration at parasympathetic nerve synapses and an increase in colon peristalsis.

Other factors that likely contribute to the pathogenesis of ACPO are chronic underlying bowel motility disorders and constipation, patient immobility, electrolyte imbalance, medications such as narcotics, and mechanical ventilation. These other factors may contribute to the autonomic imbalance, directly suppress muscular function of the colon, or simply increase the amount of gas that is entering the digestive tract. At least 50% of patients with ACPO have significant electrolyte abnormalities, especially low potassium, magnesium, and calcium.4 Secretory diarrhea (with high potassium and low sodium concentration in the stool) can occur in ACPO. This is thought to be due to the effect of autonomic nervous system disturbance and of colonic distension on the activity of the apical (BK) potassium channels in the colonic mucosa.44

Usually the perforation risk is not very high in patients with cecal diameter less than 12 cm. Paradoxically, studies have shown that patients with ACPO and cecal diameter greater than 25 cm can recover without incident. Other variables, such as elasticity of the muscle wall, adequacy of blood supply, and time course of distention must be important as well in determining whether the colon remains viable. Some studies indicate an association between the duration of ACPO and perforation risk and indicate that patients with persistence of distention for more than 5 days have higher perforation rates.45

Clinical Features

ACPO is seen mainly in patients who are hospitalized for an acute medical, surgical, obstetric, or traumatic event. The condition progresses at a variable rate, usually over 2 to 7 days. The nearly universal symptom is progressive abdominal distention. The reported frequency of other symptoms is quite varied. Abdominal pain (10% to 80%), nausea (10% to 60%), vomiting (10% to 60%), diarrhea (30% to 40%), constipation (40% to 50%), and respiratory compromise resulting from distention all have been reported.3–57 Patients with ischemia and perforation are much more likely to have abdominal pain and fever.

Laboratory abnormalities include an elevated white blood cell count in up to 25% of patients without perforation and in almost 100% of patients with perforation.4 Abnormalities in electrolytes such as potassium, calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus and abnormalities in thyroid function are not caused by ACPO but are thought to contribute to colonic dysfunction. These laboratory values should be checked and corrected, if abnormal.

Abdominal x-ray films show colonic distention, usually most pronounced in the cecum, ascending, and transverse colon. In contrast to patients with severe obstipation, the colon is distended primarily with gas, not stool. There is often an apparent “cutoff” near the splenic flexure with a collapsed left colon. The location of the cutoff varies. In one review, the cutoff was at the splenic flexure in 56% of patients, at the hepatic flexure in 18%, and at the descending or sigmoid colon in 27%. Although the small bowel is said usually to have less dilation in ACPO, one report indicated 80% of patients had some small bowel dilation. Air-fluid levels have been reported in 40%. X-ray evidence of gas in the bowel wall or free intraperitoneal air is indicative of colonic perforation. Radiographic water-soluble contrast enemas are often needed to rule out a true mechanical obstruction. As discussed in the treatment section, the use of water-soluble contrast material has been reported to have a therapeutic effect in some patients.46

Differential Diagnosis

Toxic megacolon resulting from infections such as Clostridium difficile should be considered in patients who have been exposed to antibiotics or prolonged care in a hospital or nursing facility, where they may have contracted the infection. Generally, such patients had severe diarrhea before the onset of the abdominal distention. Other colonic infections leading to toxic megacolon have been reported, particularly in immunosuppressed patients. In some cases, these patients seem to have a presentation indistinguishable from classic ACPO. However, when the colonic distention is due to infection, patients usually have an elevated white blood cell count; thickening of bowel wall on x-ray films; and endoscopic evidence of severe colonic erythema, edema, ulceration, or pseudomembranes on flexible sigmoidoscopy. Stool studies for enteric pathogens and C. difficile toxin are important in this setting.47

Similarly, toxic megacolon resulting from IBD can usually be differentiated from ACPO by a review of clinical history, laboratory results, x-ray films, and findings on sigmoidoscopy.48 Patients with IBD should have had a history of diarrhea (often bloody) and abdominal cramps before the development of colonic distention. Blood test results usually show leukocytosis. Abdominal x-ray films often show bowel wall edema. Sigmoidoscopy should show changes consistent with IBD. Lastly, the presence of chronic pseudo-obstruction can often be excluded by a careful review of the patient’s history, old records, and prior abdominal radiographs when available.

Treatment

Because ACPO is uncommon, there have been few controlled trials of the treatments that are currently considered the standard of care. Most data are from reviews, observational studies, and case presentations. Therapy is generally divided into conservative measures and active interventions. Because at least 75% of patients with ACPO experience resolution with a combination of conservative measures, these are generally tried first for at least 24 to 48 hours in most patients before more active interventions are considered.49 The reported success from these measures ranges from 33% to 100%.25–27

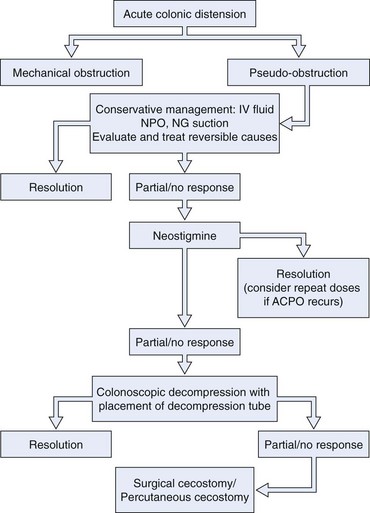

The following sections describe conservative therapy, medication therapy, colonoscopy, and surgical approaches for ACPO. These treatments are often combined. Conservative measures are typically continued when more active interventions are added. The order and combination of these measures must be individualized to a patient’s clinical presentation and course. There have been a number of excellent recent reviews on the topic of treatment of ACPO.50–56 Fig. 24.1 outlines a proposed treatment algorithm for most patients with ACPO, modified from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy practice guideline on treatment of this condition.49

Conservative Therapy

Conservative measures for treatment of ACPO include most, if not all, of the following, depending on individual circumstances.38 The patient is made nil per os (NPO), and nasogastric suction is used to prevent more gas from entering the gastrointestinal tract. Patients are mobilized as much as possible. If the patient is bed-bound, the patient’s position should be changed often from side to side and, when possible, into the prone and knee-to-chest position. A search for contributing factors should be done with correction of as many as possible. One should withdraw medications that interfere with colonic motility, such as narcotic analgesics, anticholinergics, and calcium channel blockers. Electrolyte imbalance (especially potassium, calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus) should be corrected. Regular rectal examinations every 6 hours have been advocated as a way to encourage passage of colonic gas. Placement of a rectal tube is more often used for this purpose. Gentle tap water enemas are controversial but are advocated by some authors as a way to liquefy remaining stool. A water-soluble contrast enema, which can liquefy stool, is commonly performed to exclude mechanical obstruction. Some authors have reported a stimulant effect on motility that sometimes speeds recovery.46 Prophylactic antibiotics have not been studied and are not common practice. If a patient has a fever or elevated white blood cell count, broad-spectrum antibiotics can be considered while a careful evaluation is under way for signs of colonic ischemia, perforation, or other infections.

Conservative measures are continued for 24 to 48 hours before more active intervention is initiated. This recommendation is not based on controlled data but rather on the observation that patients whose severe colon dilation (>12 cm) persists for 4 to 5 days have a higher risk of ischemia and perforation.4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree