- Investigation of masses in the liver is largely radiological and biopsy is only necessary if radiological investigations fail to identify a cause with certainty.

- Hemangiomas are harmless and once diagnosed do not need any further follow-up.

- Hepatocellular carcinoma is no longer the universal death sentence it once was.

- Regular screening liver ultrasound can identify the majority of cancers at a size that is amenable to cure.

- Therefore all patients with cirrhosis of any cause should undergo 6-monthly surveillance.

- Patients with hepatitis B at risk for hepatocellular carcinoma should be identified using published nomograms.

- Regular screening liver ultrasound can identify the majority of cancers at a size that is amenable to cure.

There are many different tumors that may grow in the liver. Apart from metastases from other organs, most are rare and do not merit more than a passing mention. Liver abscesses are not common, but are potentially fatal and so deserve mention. This discussion will therefore be limited to abscesses and to the three most common benign masses or tumor-like lesions, hemangioma, focal nodular hyperplasia, and hepatic adenoma, and the two most common malignant tumors of the liver, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC). These five entities account for the vast majority of nodular lesions found on radiological examination of the liver in children and adults.

Liver Abscess

Patients with a liver abscess usually present with fever and pain in the right upper quadrant. They are more frequent in areas of the world where hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is also prevalent—a simple clinical test to differentiate the two is to “spring” the lower chest—the individual with an abscess will feel sudden pain whereas this is unlikely if the liver mass is an HCC.

Amoebic Liver Abscess

Entamoeba histolytica may exist in an environment in a “vegetative” form. When consumed it excysts in the colon to the trophozoite form and may invade the mucosa (possible over several years) causing “flask-shaped” ulcers, which lead to systemic infection, initially via the portal system to the liver but may also be transported to the lungs and brain. The organism produces proteolytic enzymes, which causes the microabscesses to coalesce to a large abscess, generally in the right lobe of the liver.

The patient may present just with fever or just weight loss and/or abdominal pain. Typically, the patient is found to have an elevated serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) without anemia. Ultrasound shows the presence of an intrahepatic fluid collection. If the edge of the abscess is close to the liver surface rupture is imminent, and treatment needs to be instituted quickly. Diagnosis can be confirmed serologically with antibody tests—EIA and fluorescent antibodies (IgG). But, since this takes time, often treatment has to be instituted before these test results are available. The radiological appearances (ultrasound or CT scan) are often typical and allow rapid diagnosis. Aspiration of the abscess may be necessary for diagnosis if radiology is not typical. It is important to drain all of the red/brown necrotic material (“anchovy paste”) because the amoebae are found in or close to the abscess wall, and are often only found in the last samples taken. Treatment with metronidazole 750 mg t.i.d. for 5–10 days is curative and the outcome is excellent. If drainage for diagnosis has not been required, drainage is not standard therapy but may be required in abscesses that are at risk of rupture.

Pyogenic Liver Abscess

Pyogenic liver abscess is much harder to diagnose as it has an insidious onset and often complicates other intra-abdominal or systemic diseases. The risk factors include:

- recent surgical, endoscopic, or radiologic procedures;

- chronic biliary disease, e.g. primary sclerosing cholangitis, Caroli disease;

- damage to the hepatic artery, e.g. following infusions of chemotherapy to ablate liver tumors;

- neonatal umbilical sepsis;

- portal pyemia/septic embolus, e.g. secondary to gallbladder infection, diverticulitis, or pancreatitis;

- immunocompromised patients—those with organ transplant, leukemia, HIV infection.

The diagnosis is easy to miss as the patient is often already unwell and then further deterioration may be slow. A fall in hemoglobin and/or serum albumin commonly accompanies development of a liver abscess (or abscesses) but may be thought to be secondary to their primary disease. Abdominal pain with or without fever has an insidious onset. Leukocytosis is common, though jaundice is unusual. The diagnosis should be confirmed by ultrasound, CT scan, and/or MRI—sharp borders between normal liver and abscess become obvious. Aspiration under ultrasound guidance is required and cultures for both aerobic and anaerobic organisms should be requested.

Treatment

Treatment should be relief of biliary obstruction if present and systemic antibiotics. The prognosis for those with multiple abscesses is poor, whereas that for a single abscess is better.

Hemangioma

Epidemiology

Hemangioma is the most common liver tumor, found in up to 20% of autopsy series. They occur more frequently in women for unknown reasons. They may be single or multiple and may vary in size from a few millimeters to 10 cm or more, although most are smaller than 5 cm in diameter. They consist of vascular channels lined by a single endothelial layer, supported by fibrous tissue. The vascular spaces may contain thrombi, which may calcify.

Hemangioma is a benign lesion, and never develops into malignancy. Whether the lesion is hormone sensitive is controversial. There are case reports of enlargement of hemangiomas with pregnancy or exogenous estrogen administration. However, hemangiomas may enlarge in the absence of these stimuli. Despite this, the vast majority of hemangiomas are clearly not hormone sensitive and do not grow significantly, either spontaneously or under hormonal influences.

Diagnosis

Because the majority of hemangiomas are clinically silent, they most commonly present as an incidental finding on an ultrasound done for unrelated purposes. The diagnosis of hemangioma is radiological.1 Typically, hemangiomas are described as brightly echogenic on ultrasound. The nature of the lesion can be confirmed by one of several methods. A labeled red blood cell scan shows pooling of the label in the lesion that persists into the delayed phases (late portal phase). However, the sensitivity of this nuclear medicine study is dependent on the size of the lesion. This technique is not highly sensitive or specific, and its use is declining. Hemangiomas that are smaller than about 2 cm may not be detected by labeled red blood cell scanning. All forms of dynamic imaging, that is contrast ultrasound, tri- or four-phase CT scanning or MRI are more sensitive and specific for the detection of hemangioma2 than red cell scans. The characteristic features are centripetal filling of the lesion with contrast agent, and peripheral nodularity in the venous or late phases.

Clinical Features

Hemangiomas of the liver rarely cause symptoms. Thrombosis of very large lesions may present as pain. This can be diagnosed radiologically, using a dynamic contrast-enhanced study. Usually analgesia is the only treatment required, since once the thrombus has formed and is stable the pain will subside. Occasionally giant hemangiomas may bleed, either into the liver or into the peritoneal cavity. Rupture has also been reported associated with enlargement during pregnancy. These are exceptionally rare events, and are the only indications for resection of these lesions.

Large hemangiomas may rarely be associated with thrombocytopenia (Kasabach–Merritt syndrome), particularly in children. Fibrin deposition within the lesion has been reported to cause hypofibrinogenemia.

Practice Point.

Ultrasound is frequently the only test necessary to confirm hemangioma.

Practice Point.

Hemangioma virtually never causes symptoms and do not need to be followed at all.

Focal Nodular Hyperplasia

Focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) is a tumor-like lesion that consists mainly of normal hepatocytes and fibrous stroma. It has no malignant potential. FNH occurs more frequently in women. The etiology is unknown. Some believe that the FNH is a hypertrophic lesion that grows in response to the development of a spider-like arterial vascular abnormality. The cause of the initial vascular abnormality is unknown. In most instances, the lesion presents as an incidental finding on an imaging study ordered for other reasons. While there are reports of apparent enlargement of FNH in response to estrogen exposure it is difficult to know whether the association is real or due to selective reporting. There are few prospective series that included sufficient subjects to completely exclude the possibility that some FNHs do develop in relation to sex hormone exposure, but the vast majority of FNH are not hormone sensitive2 and do not enlarge, and the presence of an FNH is not a contraindication to pregnancy.

FNH may vary in size from smaller than 2 cm to many cm in diameter. Very large lesions may infarct or may bleed. External rupture into the peritoneum is rare. Occasionally, FNH may shrink in size or even regress completely.3

Pathology

The lesion consists of normal hepatocytes in plates two to three cells thick (compared to the single or double cell plates in normal liver). The arteries drain directly into the sinusoids between adjacent plates. In the center of the lesion there is usually a fibrous stellate scar, carrying the vascular supply (arterial only), which, if present, is characteristic of FNH.

Diagnosis

FNH can usually be diagnosed radiologically without having to resort to biopsy. Perhaps the most sensitive and specific imaging technique is contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS).3 In this technique microbubbles are injected peripherally and scanned as they flow through the liver. The microbubbles provide multiple surfaces for the incoming sound waves to reflect off, giving a very bright pattern and outlining the blood vessels. CEUS can often clearly demonstrate the feeding artery and the central stellate scar which, if present, is a diagnostic finding. Dynamic MRI and three-phase CT scan can also often show the central scar. However, even in the absence of the scar pattern the enhancement characteristics can distinguish FNH from HCC.

Treatment

Since FNH does not undergo malignant transformation only symptomatic lesions need treatment. Occasionally, very large lesions causing pressure symptoms may need to be resected. Arterial embolization is effective in reducing the size of the lesion, but may not eradicate it completely. Large FNH lesions are at risk for rupture, and may require prophylactic treatment. Lesions that do rupture also require surgical intervention, although embolization has also been used to treat these lesions.

Hepatic Adenoma

Epidemiology

This is a rare, benign liver tumor. That adenomas are frequently hormone dependent is now well established.3 The evidence of a causal association rests on small case series and the temporal relationship between the introduction of the oral contraceptive pill and a sudden significant increase in the number of case reports of hepatic adenoma appearing in the literature. The association was enforced by the finding that hepatic adenoma may enlarge during pregnancy, and may regress after delivery or on withdrawal of the oral contraceptives. Similarly, adenoma associated with androgen use may regress once the androgen therapy is withdrawn. Today’s oral contraceptives have much lower estrogen concentrations than those that were in use when the association was first recognized, and some do not even contain the C17-alkyl-substituted estrogens that have been incriminated.

Although development of hepatic adenoma is usually associated with longer-term oral contraceptive use, the development of adenoma has been described after as little as 6 months of use. Hepatic adenomas in men are seen in association with use of anabolic steroids, initially reported with therapeutic use of anabolic steroids for Fanconi anemia or aplastic anemia, and more recently following illicit use of androgens by athletes. Glycogen storage disease type 1A is associated with the development of multiple hepatic adenomas. These are usually multiple, and need to be monitored for malignant conversion. Multiple hepatic adenomatosis is a rare condition, in which the liver may contain 10 or more lesions of various sizes. This may occur in the setting of exogenous hormone administration, although there may be no such history. Hepatic adenomas tend to enlarge over time and have the potential to become malignant. The development of HCC in a pre-existing hepatic adenoma, although well described, is a rare event. Adenomas with malignant potential have a typical staining pattern for β-catenin. Therefore all adenomas should undergo biopsy to look for this staining and the malignant potential that it infers. If this staining is present this may be an indication for resection, particularly if there is no response to estrogen or androgen withdrawal.

Diagnosis

Hepatic adenomas are often incidental findings in patients undergoing radiological imaging, usually ultrasound, for other reasons. Large lesions may cause pressure symptoms, a palpable right upper quadrant mass, or rarely may present with pain due to bleeding into the tumor or rupture into the peritoneum.

Radiological diagnosis is moderately specific. Technetium-labeled liver spleen scans may show a cold area, because the adenoma contains relatively few Kupffer cells. However, this is not a highly sensitive or specific test. The ultrasound appearances are not specific. The lesion may be hyper- or hypoechoic, or of mixed echogenicity. CEUS is useful to exclude the differential diagnoses of HCC and focal nodular hyperplasia, but the appearances are not highly specific for adenoma. CT and MRI may also show rapid arterial enhancement. Other features that may be detected radiologically include the presence of fat in the lesion, abnormal vessels, or intratumoral hemorrhage. Because the radiologic features are not sufficiently specific, needle biopsy of the lesion is always required for a definitive diagnosis.

Pathology

The hallmark of the hepatic adenoma is that it consists solely of hepatocytes, arranged in chords that are seldom more than three cells wide, separated by very narrow sinusoids. The hepatocytes are often larger than normal hepatocytes and may contain fat. Kupffer cells are variably present, although usually in reduced numbers. Bile ducts are absent. Mitoses are rare. The differential diagnosis is primarily with HCC, in which the chords are usually more than three cells wide, and the overall architecture is more disorganized.

Treatment

Hepatic adenomas diagnosed in the setting of exogenous hormone administration often regress when the offending drug is withdrawn, and this constitutes the treatment of choice. Stable lesions can be watched, but growing lesions should be treated, because of the risk of complications related to bleeding or rupture, or to malignant transformation. The usual therapy in the past has been resection, but today local ablation with radiofrequency probes is more commonly used for smaller lesions.

Hepatic adenoma is not a contraindication to pregnancy. Whether treatment of the lesion is required prior to or during pregnancy is controversial. Some advocate ablation or resection of all adenomas prior to pregnancy, or in early pregnancy. This is because of the risk of rupture, which although it is usually associated with larger adenomas, can also occur with smaller lesions. However, an alternative approach would be to monitor the growth of the lesion by frequent ultrasonography and only intervene if the lesion is seen to grow. For those women who are first diagnosed with adenoma during pregnancy the same considerations apply.

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Epidemiology

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the 10 most common tumors in the world, accounting for more than 300 000 deaths each year.4 There are close epidemiological links with several diseases that predispose to the development of HCC. The vast majority of HCCs develop on the background of chronic liver disease, usually cirrhosis. HCC arising in a previously normal liver accounts for less than 10% of all HCCs. Worldwide, the most frequent underlying cause of HCC is chronic hepatitis B, followed by hepatitis C. The incidence of HCC is rising in many countries in the West. In some countries, for example Italy, there was a silent epidemic of hepatitis C infection in the period between about 1945 and 1970. In other countries epidemics of hepatitis C occurred as a result of injection drug use, a practice that became widespread during the 1960s and 1970s. Those cohorts have now been infected for up to 40 or more years and are now at risk for the development of HCC. Finally, immigration from parts of the world where hepatitis B and hepatitis C are common is also contributing to the pool of infected individuals in many Western countries, and hence also to the rising incidence of HCC.

Other causes of cirrhosis that predispose to HCC include alcoholic cirrhosis, cirrhosis associated with genetic hemochromatosis, and α1-antitrypsin deficiency, primary biliary cirrhosis, and more recently it has been recognized that cirrhosis following steatohepatitis is also a risk factor for HCC. Hepatitis B is common in South East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. In these parts of the world the incidence of HCC is more than 5/100 000 per year, and may be as high as more than 50/100 000 per year in parts of China. In contrast, in parts of the world where chronic viral hepatitis is less common, for example Northern Europe and North America, the incidence of HCC is closer to 1–5/100 000 per year and hepatitis C is the commonest cause.

Practice Point.

The high prevalence in the West of fatty liver disease and diabetes means that in future these diseases will be the most common causes of HCC.

HCC can also develop in precirrhotic chronic liver injury. This has been well documented in hepatitis B, but also occurs in hepatitis C and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. The incidence of HCC in these patients is lower than in cirrhosis.

Surveillance for HCC

Surveillance for HCC has become standard of care. This is based on several lines of evidence. A randomized controlled trial in hepatitis B carriers in China that showed that 6-monthly screening with ultrasound and α-fetoprotein resulted in a reduction in mortality of 37%.5 Several cost–efficacy analyses in various at risk populations have suggested that screening for HCC is cost effective. Patients who undergo surveillance have their HCC diagnosed at an earlier stage.6 Small HCC can be cured with appreciable frequency (>90%). However, it has become apparent that most of the benefit of surveillance comes from ultrasound, and that the use of serum measurement of α-fetoprotein adds little except cost. Overall, α-fetoprotein screening is insufficiently sensitive and insufficiently specific for general use as a screening test.7 These results have led to the recommendation by many different groups that patients at risk for HCC should undergo surveillance with ultrasound alone.8 The screening interval should be 6 months. This is based on the anticipated tumor doubling time, which on average is about 3–5 months. Patients deemed at higher than average risk do not need to be screened more frequently, since the screening interval depends on tumor growth rate, not degree of risk.

With a good ultrasound examination it is possible to detect lesions smaller than 1 cm. With appropriate follow-up and intervention, it is at least theoretically possible to cure the majority of HCC at this size (see below). Thus it is essential to identify patients at risk for HCC, to provide regular surveillance, and to thoroughly investigate lesions discovered on ultrasound to determine whether they are malignant or not.

Practice Point.

In order to achieve the best outcomes from HCC screening it is important to find the lesions when they are smaller than 2–2.5 cm in diameter, hence 6-monthly screening is better than annual. The cure rate of these lesions is better than 98%.

Diagnosis

Patients whose tumors are diagnosed through screening present with small lesions and are asymptomatic. Unfortunately, even in parts of the world where HCC is common, the majority of patients do not undergo screening, and present with late-stage disease.

HCC can be diagnosed radiologically in the majority of patients, so that biopsy is not necessary. If the typical radiological appearances are present the diagnosis is confirmed. These are that the lesion enhances in the arterial phase of a dynamic contrast study, and is less enhancing than the surrounding liver in the portal venous and late phases of the study. The mechanism is that the tumor is fed exclusively by arterial flow, whereas the liver is fed by arterial and portal venous blood. Thus, in the arterial phase the arterial blood containing contrast is diluted by portal venous blood in the liver but not in the tumor. However, in the venous and delayed phases, the tumor is fed by arterial blood that no longer contains contrast, whereas the portal venous blood in the liver now contains contrast. Lesions that do not match these criteria (and are not clearly FNH, hemangioma, or metastasis) require biopsy.

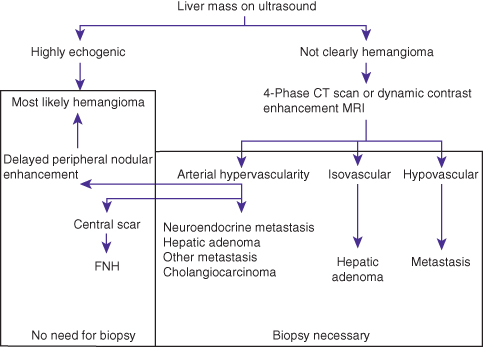

With improvements in ultrasonography in the recent past we are now able to find lesions that are smaller than 1 cm. However, the smaller the lesion, the more difficult it is to distinguish a benign from malignant nodule, either radiologically or on biopsy. Therefore the algorithm that has been developed to help distinguish these two possibilities has stratified lesions by size, either smaller or larger than 1 cm in diameter. Most lesions smaller than 1 cm are not HCC. The larger the lesion, the more likely it is to be HCC. This algorithm is shown in Figs 7.1 and 7.2.

Fig. 7.1 Algorithm for the diagnosis of a liver mass in a patient who does not have any risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma. FNH, focal nodular hyperplasia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree