- Obesity rates are increasing worldwide. Adults with a body mass index (BMI) of more than 30 (Caucasian) or more than 27 (Asian) are classified as obese and have a 10-fold increased risk of cirrhosis over the general population. Waist size may be even more relevant.

- Liver disease secondary to obesity accounts for one-third of all chronic liver disease in adults in North America.

- Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a spectrum of liver disorders, in order of severity: simple steatosis (fat only), non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH: fat + inflammation ± fibrosis), and cirrhosis.

- The prevalence of NAFLD varies according to ethnicity (greater in Asians than Caucasians) and may cluster in families, which suggests a genetic disposition.

- NAFLD is present in 70% of people who are obese but may also affect lean individuals.

- NAFLD may be associated with obesity, insulin resistance, and hyperlipidemia (in the absence of regular alcohol consumption). These three components are the main elements of the “metabolic syndrome”.

- Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which requires liver biopsy for diagnosis, is present in 18.5% of those who are obese. In severely obese individuals (BMI >40), the rate of NASH is 30%, with 2–3% having cirrhosis (if diabetic, 10–25% have cirrhosis).

- NASH is progressive: approximately 30% develop severe fibrosis after 10 years of follow-up. Regression of cirrhosis may occur with sustained weight loss.

- Nevertheless, patients with NASH more often die from coronary heart disease (10%) or extrahepatic malignancy (5%) than from a complication of cirrhosis (2%).

- NAFLD is the most common chronic liver disease in children in North America.

- Cirrhosis associated with NAFLD may occur in childhood.

- The “insulin resistance syndrome” characterizes children with NAFLD. Insulin resistance is probably acquired through an interaction of genetic make-up and environmental factors (diet, lack of exercise, poor sleep habits). The “metabolic syndrome” has not been defined in children.

- Waist circumference is highly informative for diagnosing NAFLD in children. Most, but not all, children with NAFLD have a BMI in the overweight or obese range for their age/sex.

- NAFLD must be distinguished from all other causes of fatty liver not associated with hyperinsulinemia/insulin resistance. Wilson disease is an important consideration.

- Liver biopsy is required for complete diagnosis and helps to eliminate competing diagnoses.

- No effective pharmacological treatment has been established for children. Dietary intervention with a low-glycemic-index diet and lifestyle changes to incorporate regular exercise are effective in improving the liver disease as weight loss is achieved.

Definition

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) denotes a spectrum of liver disorders associated with abnormal insulin action. The spectrum is comprised of simple steatosis (accumulation of large droplets of fat in hepatocytes without inflammation), non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH; accumulation of large droplet fat along with inflammation and/or fibrosis), and the resulting cirrhosis in which steatosis may no longer be obvious. Most people who have NAFLD are overweight or obese.

Liver test abnormalities as a consequence of obesity in the absence of excess alcohol intake are most often due to simple hepatic steatosis, which is usually not associated with advanced liver disease. NASH is a more severe liver disease associated with infiltration of the liver with inflammatory cells and progressive fibrosis. In adults, NASH is more likely to be present in older individuals (>50 years old) with a high body mass index (BMI), type 2 diabetes and elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and/or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) values, although the latter may fall to normal with disease progression.

Pathogenesis

Hyperinsulinemia is essential to the disease mechanism. Insulin resistance is the main feature, which may be a response to sustained hyperinsulinemia. Varying degrees of insulin resistance between the liver and extrahepatic tissues may account for some of the abnormalities in NAFLD. The hepatic response to insulin appears to be more disordered for lipid metabolism than for glucose metabolism. Hyperinsulinemia leads to mobilization of stored lipid (and adipocytokines) from adipose tissue and promotes hepatic steatosis. Free fatty acids (FFA) contribute to the development of hepatic steatosis and liver damage. FFA are highly toxic; they damage intracellular membranes through lipid peroxidation. FFA-mediated damage to mitochondria inhibits α-oxidation of hepatic FFA. Since insulin inhibits oxidation of FFA, hyperinsulinemia may enhance FFA damage to hepatocytes. FFA also activate hepatocellular signaling pathways related to inflammation and apoptosis. Insulin up-regulates hepatocellular SREBP-1c (sterol response element binding protein-1c). With the excess of FFA available, up-regulating SREBP-1c probably generates increased hepatocellular production of triglycerides and very-low-density lipoproteins, and thus the hypertriglyceridemia characteristic of NAFLD. Finally, insulin up-regulates a hepatocellular protein known as suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS)-3, which down-regulates hepatocellular insulin receptors. Thus, the hyperinsulinemia itself is capable of promoting acquired insulin resistance in the liver and sustaining a vicious cycle.

The transition from simple steatosis to NASH suggests contribution of additional types of hepatic injury. Possibly, FFA toxicity to hepatocellular organelles accumulates and, additionally, FFA activate various inflammatory or fibrogenic pathways. It is unclear why most obese individuals have simple hepatic steatosis rather than NASH. Oxidant stress, inflammatory cytokines, and low-grade systemic inflammation may play a role. Some inflammatory cytokines may exacerbate hepatocellular insulin resistance and mitochondrial dysfunction. In individuals with NASH the cell injury in the lipid-laden hepatocytes promotes oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation. It has been suggested that the abnormal disposal of hepatic fat in obese individuals is a result of impaired autophagy. Accumulation of fatty acids in hepatocytes promotes endoplasmic reticulum stress, which induces proinflammatory cytokines, which promote the deposition of collagen in the liver causing progression of hepatic fibrosis associated with impaired generation of new hepatocytes.

In children, an important question is how this disease process gets started. It is most likely that over-nutrition and lack of physical exercise lead to critical metabolic changes, which involve sustained hyperinsulinemia and consequently hepatic steatosis. The prevalent “junk-food diet” of developed countries is delicious and fun to eat, and it is high in calories from sugars (notably sucrose and fructose) and saturated fats, and low in antioxidants and fiber. Studies in rodents have demonstrated repeatedly that this kind of diet creates hyperinsulinemia and hepatic steatosis. Children who spend much of their time in front of screens (television, computer, or hand-held games), who are chauffeured from one place to another, or who have no opportunities for sports and safe playgrounds are at risk. Likewise, for reasons not yet clear, children who do not get enough sleep are likely to be overweight/obese with attendant metabolic abnormalities.

Genetic predispositions clearly exist, although identification of relevant genes is incomplete. Some of these genes regulate metabolic processes. Some genes may relate to inflammatory injury.

Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Adults

Epidemiology

The risk of NAFLD in adults correlates with BMI. In those who are obese, simple steatosis can be found in 70% (whereas hepatic steatosis is reported present in liver tissue in 3.5% of individuals with a normal BMI) (Table 17.1). NASH is present in 18.5% of those who are obese, but 2.7% of cases are lean individuals who may have been obese when younger. In those with severe obesity (BMI > 40), typically 60% have simple steatosis, 30% have NASH, and 1% cirrhosis, but the percentage with cirrhosis increases if diabetes is present.

Table 17.1 Epidemiology of liver disease related to obesity in adults

| Ethnicity | Greatest in Asians, least in African Americans |

| Prevalence | Responsible for 1/3 of all chronic liver disease in the non-alcoholic in North America |

| Obesity (BMI > 30 in Caucasians, >27 in Asians) | 70% hepatic steatosis, 20% steatohepatitis, rate of cirrhosis unknown |

| Severe obesity (BMI > 40) | 90% steatosis, 30% steatohepatitis (2–3% cirrhosis) |

| Diabetes (type 2) | 75% have hepatic steatosis |

| Hyperlipidemia | ↑ Triglycerides, 60% NAFLD ↑ Cholesterol, 30% NAFLD |

| Familial | Genetic, also related to common eating habits and exercise pattern |

BMI, body mass index; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Individuals of Asian origin are at the highest risk of NAFLD whereas African Americans are at least risk. For Hispanics the risk is between that for Asians and African Americans. It is unclear whether familial disease is genetic or related to common eating and exercise habits, but it is obvious that NAFLD is highly influenced by an imbalance between overall calorie consumption and systemic calorie utilization.

Clinical Features

As in most with a chronic liver disease, the affected individual remains free of symptoms or signs, although some may have acanthosis nigricans and/or a buffalo hump (Box 17.1). Thus physicians need to have a high index of suspicion in obese subjects (particularly in those with abdominal obesity), who are physically inactive with or without elevation of serum aminotransferase levels.

- Eating pattern (including soft drinks/fruit juice)

- Exercise pattern

- Alcohol intake

- Body weight, current and past

- Family history of liver disease and metabolic syndrome (diabetes)

- Hirsutism (polycystic ovary syndrome)

- Body mass index and waist circumference

- Buffalo hump

- Acanthosis nigricans

- Skin stigmata of cirrhosis (unusual)

- Systemic blood pressure

- Evidence of peripheral vascular disease

- Hepatomegaly—texture

- Splenomegaly (if present check for varices)

- Ascites, hepatic encephalopathy

Individuals with NAFLD may not be obese at the time of diagnosis; thus it is important to establish prior body weight in all individuals with abnormal liver tests.

Sometimes the individual gives a history of non-specific abdominal pain (often in the right upper quadrant). Associated disorders include systemic hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and type 2 diabetes.

A frequent misunderstanding is that the degree of elevation of the serum aminotransferase values is a guide to the severity of the underlying liver disease. In the setting of probable NAFLD, this misunderstanding compromises diagnosis of this disease. Thus any individual who is overweight, particularly with central obesity, should be a “suspect” for NAFLD and worked up appropriately. Liver enzyme levels may be within the normal range, especially in those with advanced disease.

Before the diagnosis of NAFLD can be made, it is essential to make an in-depth evaluation of both current and past alcohol intake (see Chapter 15). Women are more susceptible to alcohol-mediated liver disease than men. In women, more than 20 g alcohol/day and men more than 30–40 g alcohol/day may be hepatotoxic regardless of the type of alcohol consumed (see Chapter 8).

Associated Disorders in Adults

Individuals found to have a fatty liver may also have type 2 diabetes, and 75% of those with type 2 diabetes have a fatty liver. In individuals with elevated serum triglycerides, 60% have a fatty liver whereas only 30% of those with an isolated elevation of serum cholesterol have a fatty liver.

Fatty liver is often associated with systemic hypertension, less often with hyperuricemia, polycystic ovary syndrome, sleep apnea, and small bowel bacterial overgrowth (Box 17.2). Most individuals with a fatty liver will have impaired exercise tolerance, as measured by oxygen consumption during exercise.

- Metabolic syndrome (↑ uric acid, ↑ BP, ↑ lipids, ↑ cholesterol)

- Polycystic ovarian syndrome

- Sleep apnea

Those who have had chemotherapy for blood dyscrasias or other tumors and those who undergo surgery on the pituitary gland may be at an increased risk for developing NAFLD. Whether women with hypothyroidism are at increased risk for NAFLD remains unknown.

Differential Diagnosis

The major disease entity in adults is alcoholic fatty liver disease. Other causes of hepatic steatosis are intake of specific hepatotoxins, certain medications such as methotrexate, total parenteral nutrition, kwashiokor, and some genetic disorders (Box 17.3).

- Total parenteral nutrition

- Drugs: methotrexate, stavudine, didanosine, amiodarone, prednisone, L-asparaginase

- Toxins (industrial)

- Kwashiokor

- Small bowel bacterial overgrowth

- Genetic diseases: Wilson disease

Reye syndrome and fatty liver of pregnancy are very different; their clinical presentation is highly specific and liver histology shows only microvesicular fat.

Evaluation of Liver Disease

Severity of liver disease in adults with NAFLD is in part age dependent, cirrhosis being unusual before the age of 50. Not uncommonly, cirrhosis is a chance finding at the time of abdominal surgery. In this situation, volume and/or salt overload postoperatively is a frequent complication, which may precipitate the onset of ascites. Other manifestations of portal hypertension, such as bleeding varices, may be problematic. As is the case with all cirrhotic patients, there is an increased chance of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). As both the early detection of HCC using 6-monthly liver ultrasound examinations and its treatment markedly improve survival, it is most important to evaluate the severity of liver disease in everyone suspected of having fatty liver disease.

NASH cannot be diagnosed accurately without a liver biopsy and those at greatest risk of NASH are the elderly and those with very high BMI, type 2 diabetes, or abnormal AST : ALT (ratio > 1).

Laboratory Features

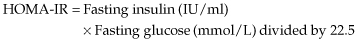

Most individuals with NAFLD will have an elevation (often very minimal) in AST and/or ALT values (Box 17.4). Simultaneous measurement of fasting glucose and insulin is used to estimate insulin resistance by employing the HOMA-IR formula, a well-validated surrogate for direct testing of insulin resistance.

- CBC (low platelet count is a marker of cirrhosis)

- Liver biochemistry AST : ALT ratio; and electrolytes

- Liver function tests: INR, serum albumin, and bilirubin

- Fasting glucose and insulin (to compute HOMA-IR)

- Fasting (12 h) cholesterol and triglycerides

- Serum uric acid

- Ultrasound of the liver (regardless of above results)

The HOMA-IR is abnormal in adults if it is greater than 2. Other possible laboratory abnormalities include hypertriglyceridemia, hypercholesterolemia, hyperuricemia, elevated IgA levels, and detectable antinuclear antibody (ANA) in 25–30% of those with NASH.

Investigations

Although examination of liver tissue is the gold standard, it is clearly not feasible to perform this in everyone thought to have NAFLD! However, in those who are most at risk of progressive liver disease, such as type 2 diabetic patients who are obese, liver biopsy is the preferred test for correct diagnosis if NAFLD is suspected. The new non-invasive tests used to measure degree of hepatic fibrosis are not reliable in obese individuals and do not allow evaluation of the degree of hepatic inflammation.

Any patient with suspected NAFLD and at high risk for cirrhosis requires a thorough preoperative work-up prior to any surgery. It is important to know preoperatively whether cirrhosis is present or not. Numerous precautions are necessary in any patient with cirrhosis of any etiology before, during, and following any surgical intervention so as to prevent postoperative hepatic decompensation with ascites, variceal hemorrhage, and/or hepatic coma (see Chapters 4 and 6).

Natural History

The outcome of patients identified as having a fatty liver obviously depends on the severity of their background liver disease, but even in those with cirrhosis death is more likely to be a consequence of concurrent vascular disease, that is coronary artery disease. Those with simple steatosis have been thought to normally run a benign course. However, these figures are from patients diagnosed with NAFLD 20–30 years ago and may not represent the outcome of those diagnosed with NAFLD in the 21st century simply because the management of coronary artery disease has improved greatly.

Of those found to have NASH without prominent fibrosis on their first liver biopsy, one-third will progress to severe fibrosis, or even cirrhosis, over 5–10 years, particularly those who also have inflammation in the portal tracts. Hepatic failure in those with cirrhosis due to NASH occurs in 17% at 1 year, 23% at 3 years, and 52% at 10 years. Liver failure is frequently precipitated by surgery (see Chapters 5, 6, and 8), particularly if this is abdominal or cardiac. However, bariatric surgery for gross obesity is not necessarily contraindicated as the consequent weight loss can lead to reduction of insulin resistance and diabetes. An additional 10–12% will die (often of other causes) over a 10 to 15-year follow-up. Hepatocellular carcinoma is confined to patients with NASH, usually those with cirrhosis.

Management

The most effective therapy is to institute dietary changes, as well as promote a regular exercise program (Box 17.5). In those who make these changes in lifestyle, a 10–15% weight reduction promotes loss of fat within the liver and will also reduce inflammation and liver cell injury. This is accompanied by a reduction in insulin resistance. Success with this relatively simple intervention lowers both liver and cardiac risk. Most important among the dietary changes is the need to eliminate the intake of concentrated fructose syrup (present in most soft drinks and in many other foods) which increases triglycerides. It remains unproven as to whether increasing the intake of omega-3 fatty acids improves fatty liver. Regular exercise improves glucose disposal in skeletal muscle mitochondria regardless of whether or not the exercise is accompanied by weight loss, hence the term “fit–fat”.