- Imaging is essential when evaluating the patient with suspected hepatobiliary disease.

- Ultrasound is the first choice when imaging the majority of these patients.

- Ultrasound is widely available, portable, inexpensive, and does not use ionizing radiation.

- Ultrasound will frequently answer the clinical question alone or will direct the next most appropriate imaging investigation.

- Computed tomography, magnetic resonance, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, endoscopic ultrasound, and image-guided biopsy may be necessary beyond ultrasound, either alone or in combination for certain diagnoses.

Radiologic Examination in Liver Disease

Acute Hepatic Failure

Acute hepatic failure is an uncommon but devastating syndrome that leads to death or a need for liver transplantation in greater than 50% of cases.1 There are numerous causes with viral hepatitis, drug toxicity, and idiosyncratic reactions amongst the most common. Frequently, imaging of the liver will be normal in these cases but should be performed to investigate the possibility of an acute event such as hepatic vein or portal vein thrombosis. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy and diffuse tumor infiltration of the liver by hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), metastases, leukemia, or lymphoma may also rarely present with acute hepatic decompensation and will be suggested by imaging.

Acute hepatic vein thrombosis (Budd–Chiari syndrome) is a rare condition that occurs with or without thrombosis of the inferior vena cava (IVC). The typical patient in the developed world is a young adult woman taking the birth control pill. Other causes include coagulation abnormalities, trauma, pregnancy, and tumor extension from HCC, renal cell cancer, adrenal cortical cancer, and leiomyosarcoma of the IVC. There are also congenital causes and obstructing membranes. The clinical course is dictated by the acuity of onset, degree of occlusion, and the presence of a collateral circulation to drain blood from the liver. These patients are generally well evaluated by ultrasound with Doppler. In the acute phase, the liver is enlarged and ascites is invariably present. The caudate lobe is often spared and hypertrophy will occur over time due to its independent venous drainage through the emissary veins directly into the IVC. Evaluation of the hepatic veins may show acute thrombosis or possibly stricturing, fibrosis, or complete obliteration. Doppler ultrasound will document flow direction in patent segments of the hepatic veins and IVC, and will also document the development of venous collaterals. Portal blood flow may also be affected and can be slowed or reversed. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may give a more global picture of the liver, including vascular anatomy and may aid in treatment planning.

Assessment of Steatosis, Fibrosis, and Cirrhosis

Imaging is part of the work-up of patients found to have elevated liver enzymes during medical assessment. Ultrasound is the most appropriate initial imaging investigation. Diffuse fatty infiltration of the liver is suggested by increased echogenicity of the liver relative to the kidney. If severe there will be poor penetration of the liver with poor visualization of the hepatic vessels and diaphragm. Often there are areas of focal fatty sparing, which help support the diagnosis. The interpretation of fatty infiltration with ultrasound remains subjective, even in experienced hands, and it is not possible to quantify the degree of fatty infiltration beyond mild, moderate, or severe.

Fatty infiltration of the liver can also be diagnosed with CT scan as reduced attenuation of the liver relative to the spleen. Unenhanced images are the most accurate. Again, it is possible to grade the infiltration as mild, moderate, or severe but it is not possible to accurately quantify the degree of fatty infiltration with routine CT, particularly with milder degrees of fatty infiltration. Research is being conducted on the benefits of dual energy CT in quantifying the degree of fatty infiltration but to date the results are not promising.2

Chemical shift MR imaging and MR spectroscopy are the most accurate non-invasive methods to detect fatty infiltration of the liver and to date are the most sensitive non-invasive methods of quantifying the degree of fatty infiltration, particularly in patients with milder involvement.3 MR is not as widely available as the other modalities and MR spectroscopy is not available at every center. However, chemical shift MR imaging is routinely used as a first-line fat quantification method in specialized centers for specific clinical settings, such as in live liver donor assessment.

Patients with elevated liver enzymes may be found to have unsuspected changes of cirrhosis. Also, patients with known risk factors for chronic liver disease are at risk of developing cirrhosis and imaging may be performed to detect changes of cirrhosis and portal hypertension. In general, early stages of cirrhosis are difficult to diagnose but once cirrhotic changes are confidently identified imaging has a high specificity. Morphologic changes of cirrhosis can be confidently detected with ultrasound, CT, and MRI. The common signs of cirrhosis include surface nodularity of the liver (better appreciated in the presence of ascites), nodularity of the hepatic vein/parenchymal interface, heterogeneous liver parenchyma and lobar redistribution with typically atrophy of segments 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8, and hypertrophy of segments 1, 2, and 3. Signs of portal hypertension are also important and if detected are highly suggestive of cirrhosis in the correct clinical context. Findings include ascites, splenomegaly, patency of the parumbilical vein, dilation of the portal vein, loss of phasicity in flow in the hepatic veins, and once advanced reversed flow in segments of, or the entire, portal venous system. Ultrasound with Doppler is excellent at demonstrating these features but if in doubt CT and MR will give a more global picture of the liver morphology and may demonstrate additional features including siderotic nodules in the liver and, in the case of MRI, Gamna–Gandy bodies in the spleen. Liver biopsy remains the gold standard for early stages of cirrhosis. It is, however, an invasive procedure, which can be associated with significant morbidity and rarely mortality making it less acceptable to patients. The accuracy may also be as low as 80% because of specimen size and fragmentation, sampling error, and interobserver variability.

There is currently much interest in developing elastography as a non-invasive method of detecting and grading fibrosis. The principle of these methods is to non-invasively measure liver stiffness as a predictor of fibrosis. Both ultrasound and MR elastography hold much promise4,5 and when used in conjunction with serological markers are clinically useful in reducing the number of liver biopsies. With transient elastography (FibroScan, Echosens, France) an ultrasound transducer is located at the end of a vibrating piston that produces a vibration of low amplitude and frequency, which generates a shear wave that passes through the skin and liver tissue. The ultrasound then detects the propagation of the shear wave through the liver at a depth of 2.5 to 6.5 cm from the skin surface by measuring its velocity. The shear wave velocity is directly related to tissue stiffness with a higher velocity equating to higher tissue stiffness, corresponding to an increasing severity of fibrosis; its great advantage is it can be done in the clinic.

MR elastography uses a similar principle but instead of ultrasound, magnetic resonance is used to follow the propagation of the shear wave through the liver, ultimately producing a computer-generated, color-coded elastogram of the liver showing the stiffness in various areas of the organ. Higher tissue stiffness corresponds to increasing severity of fibrosis.

Portal vein thrombosis is an important complication of cirrhosis and can result in sudden hepatic decompensation. The thrombosis may be bland or result from tumor infiltration from hepatocellular carcinoma. As in Budd–Chiari syndrome, ultrasound with Doppler is an excellent initial means of evaluation and can distinguish between benign and malignant thrombus in cirrhotic patients. Pulsatile arterial flow from within the thrombus has 95% specificity for the diagnosis of malignant thrombus.

Hepatic cirrhosis can be mimicked by several conditions. Congenital hepatic fibrosis, nodular regenerative hyperplasia, hepatic schistosomiasis, diffuse hepatic metastasis, and so-called pseudocirrhosis of the liver can all morphologically appear as cirrhosis. Congenital hepatic fibrosis is often manifest by complications of portal hypertension, but despite abnormal hepatic morphology and occasional regenerative nodules which may mimic malignancy, it is not associated with liver failure or hepatocellular carcinoma. It is associated with medullary sponge kidneys, cystic renal diseases, and Caroli disease. When chemotherapy leads to regression of certain hepatic metastases, especially breast carcinoma, a residual fibrotic scar with adjacent liver hyperplasia is seen. If the metastatic disease was diffuse, the regressed disease appearance mimics cirrhosis, and is called “pseudocirrhosis”.

Surveillance for Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Surveillance for HCC has been shown to improve survival, particularly in individuals chronically infected with hepatitis B or in any cirrhotic patient, and is advocated by the American, European, and Asian–Pacific societies for the study of liver diseases.6–8 Populations at risk that benefit from surveillance have been defined, with some differences for each region; however, all advocate use of ultrasound primarily as the imaging surveillance technique. Surveillance frequency is recommended at 6-month intervals. Due to the difficulty in detection of malignancy in a diseased liver and operator dependence of ultrasound, it is important to perform surveillance at centers with established expertise.

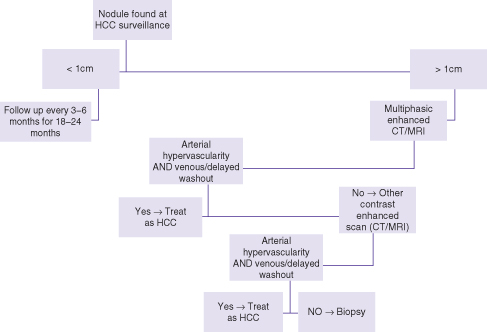

The algorithm for work-up of nodules found on surveillance depends on their size (Fig. 26.1). Nodules under 1 cm can be followed by ultrasound in 3–6 months for 18–24 months. Practically speaking, such nodules can be followed on routine surveillance, provided that it is at no longer than 6-month intervals. A nodule measuring 1 cm or more is considered significant and requires contrast-enhanced imaging work-up. While any of contrast-enhanced CT, MRI, or ultrasound is advocated as the initial work-up scan, our preference is MRI since it consistently covers the whole of the liver (compared to contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) in some patients), does not use ionizing radiation (compared to CT scan), and may provide slightly improved specificity due to additional means of tissue characterization unique to MRI.

Fig. 26.1 Algorithm for management of nodules found at HCC surveillance.

Modified from Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology 2011; 53: 1020–2.

A nodule is considered malignant when it demonstrates, relative to the adjacent liver, higher enhancement in the arterial phase (i.e. arterialized) and lower enhancement in the venous or equilibrium phases (i.e. relative washout).7 In a known cirrhotic patient or individual with chronic viral hepatitis, this pattern is considered sufficiently specific for HCC and treatment can commence without tissue biopsy. Otherwise, the scan is equivocal and a second contrast-enhanced scan is recommended (e.g. CT or CEUS).7,9 If both scans are equivocal then biopsy is advocated, which is almost always by ultrasound guidance. Follow-up by imaging is reserved for nodules that cannot be biopsied due to inaccessible location or “indeterminate” biopsy results. In the course of imaging work-up, additional nodules are sometimes found, which were not visible on ultrasound. These too need to be followed by the imaging modality that discovered them if their enhancement characteristics are not typical for malignancy.

The recommended follow-up of nodules by imaging is for a period of 18–24 months.7 If a nodule is unchanged in size and enhancement characteristics during this interval or resolves, it is considered benign and the patient can return to routine surveillance. Also, when a nodule seen on surveillance is shown to be benign in its work-up (e.g. hepatic lobulation, hemangioma, or enhancing similar to the background liver in all phases) the patient can return to routine surveillance by ultrasound.

Assessment of Liver Masses

Liver masses are often well characterized by imaging, and biopsy is rarely required. Contrast enhancement is required for CT, MRI, and ultrasound to substantially improve both sensitivity and specificity of imaging. The dual vascular supply of the liver is used to advantage with multiphase studies using intravenous contrast bolus injection; the arterial and portal vein supply of masses relative to the liver is thus used to characterize lesions. A scan prior to injection (unenhanced phase) determines the relative attenuation of the mass and also allows measuring relative enhancement upon contrast instillation. After injection of contrast material into a peripheral vein it first enters the liver through the hepatic artery (arterial phase). Relatively more contrast material enters the liver when enhanced blood returns from the gut through the portal vein (portovenous phase). After about 3 min, the concentration of contrast in the vascular system has equalized (equilibrium phase) and imaging at this late phase reflects the relative vascular volume, which indirectly indicates the fibrotic component of lesions.

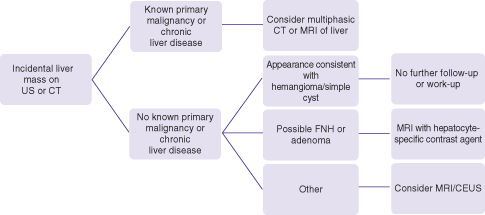

The incidental liver mass is commonly discovered when an unenhanced ultrasound or single (often portovenous) phase CT of the abdomen is performed for unrelated reasons (Fig. 26.2). Incidental asymptomatic masses are almost always benign and care should be taken not to perform extensive imaging or follow-up unless deemed necessary. Also, contrast-enhanced MRI and ultrasound are preferable when working up such lesions in order to minimize ionizing radiation of CT scan. The initial imaging scan often can characterize cysts and hemangiomas with relative high specificity and in patients without a history of prior malignancy or of chronic liver disease, further imaging work-up or follow-up is not necessary. The contrast enhancement pattern of hemangiomas is highly specific and can make the diagnosis when the initial imaging with ultrasound is equivocal. The hepatobiliary phase of hepatocyte-specific MRI contrast agents is highly specific for focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) and is primarily recommended when these common lesions (in 3% of the population) are to be differentiated from hepatocellular adenoma.

Fig. 26.2 Algorithm for the work-up of incidental masses found on abdominal ultrasound or CT scan.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree