- Any acute viral hepatitis may present in three main ways: asymptomatic, symptomatic, or as a fulminant hepatitis.

- There are five well-characterized hepatitis viruses (HAV, HBV, HCV, HDV, HEV), and each of these viruses is distinct. HBV is a DNA virus; the others are RNA viruses, and HDV is an incomplete virus.

- Serological markers are used to differentiate individuals with acute viral hepatitis from those with chronic viral hepatitis.

- Treatment consists mainly of general supportive measures although some virus-specific therapies are available.

- Vaccinations are available for protection against HAV and HBV infection, and a vaccine against HEV is being developed. Immunity to HBV also provides protection against HDV infection. In North America, universal vaccination of infants/young children against HAV and HBV is the standard policy. There is no vaccine against HCV currently available.

- Standard public health measures such as clean water, single use of all medical/dental equipment that pierces the skin, and the practice of safer sex can impact global outcomes.

Introduction

Several viruses, such as adenovirus, cytomegalovirus, echoviruses, Epstein–Barr, herpes simplex, varicella, and rubella, may cause “hepatitis” as a component of a systemic disease, but certain viruses, namely hepatitis viruses A, B, C, D, and E, cause a hepatitis of variable severity as their primary effect (Box 12.1). Inoculation of a non-immune host with any of these five unrelated viruses results in one of three clinical syndromes: (1) asymptomatic disease; (2) acute hepatitis; or (3) fulminant hepatitis (Table 12.1). The risk for development of these different manifestations of acute viral hepatitis depends upon both virus and host factors.

Table 12.1 Definition of syndromes associated with acute viral hepatitis

| Syndrome | Clinical manifestations | Biochemical manifestations |

| Asymptomatic infection | Absence of symptoms | Mild elevation in aminotransferases Normal liver function (INR, bilirubin, albumin) |

| Acute hepatitis | Preicteric symptoms including fatigue, nausea, anorexia, flu-like symptoms Hepatomegaly and liver tenderness Can progress to icteric illness (more severe symptoms) | Mild–moderate elevation in aminotransferases Mild–moderate elevation in bilirubin |

| Fulminant hepatitis | Initial symptoms resemble acute hepatitis but then rapid development of jaundice, edema, ascites, confusion (encephalopathy), bleeding | Presence of active infection Moderate–severe elevation in aminotransferases Markers of liver failure (high INR, high bilirubin) |

Hepatitis A

Virology

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) was first characterized in 1973. HAV contains a single-stranded RNA molecule and lacks an envelope. Only one serotype of HAV is known, and there is no antigenic cross-reactivity with hepatitis B, C, D, or E. HAV can survive acidic environments (down to pH 3) and high temperatures (60°C for 60 min). HAV is capable of surviving in dried feces for up to 4 weeks.

Epidemiology

HAV transmission is by the fecal–oral route. It is primarily transmitted either person-to-person or by ingestion of contaminated food and water. Only very rarely does transmission take place by blood-to-blood contact such as via transfusion or injection drug use. It is also present in all bodily fluids of an infected person and can be transmitted via contact.

HAV infection follows one of three epidemiologic patterns.

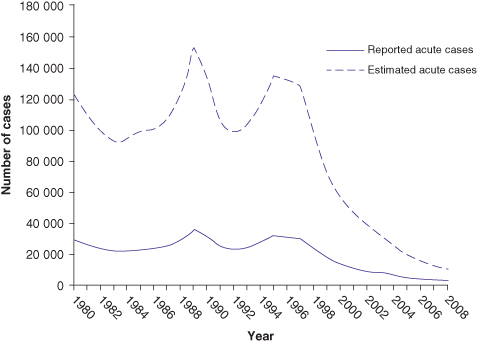

Fig. 12.1 Incidence of acute HAV infection in the United States

(data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

Clinical Features

HAV infection results in an acute self-limited episode of hepatitis and never results in chronic infection. There are usually five different clinical patterns:

The clinically silent incubation (preclinical) phase is usually 2 to 4 weeks during which time viral transmission is likely as HAV is readily detectable in stool and blood. A prodromal illness can include fatigue, anorexia, nausea, weakness, and right upper quadrant abdominal pain. Eventually, jaundice and dark urine may develop. Symptoms, if present, last from a few days to 2 weeks. Complete clinical recovery is observed in 60% of affected individuals in 2 months and nearly all individuals by 6 months. The overall prognosis is excellent. After full recovery the anti-HAV antibody is protective against reinfection.

In general, the severity of clinical illness increases with increasing age. Children under 2 years are typically asymptomatic and jaundice occurs in only 20%. After age 5 years, most (80%) infected individuals will experience symptoms. A relapsing course is observed in about 10% of patients with HAV infection. Profound cholestasis may complicate acute HAV infection especially in those taking estrogens (including the very-low-dose oral contraceptive formulations). Approximately one-third of individuals infected after age 60 years will require hospitalization. Women past middle age seem to be at greater risk for a more severe course of acute hepatitis A, including some predisposition to acute liver failure. Overall the risk for acute liver failure with acute hepatitis A is approximately 1%. In endemic areas, young children are at excess risk for acute liver failure from acute hepatitis A, despite the usual pattern of trivial or unapparent infection. Consequently, it has been a leading indication for liver transplantation in pre-school-aged children in these countries, for example, Argentina. Universal vaccination programs for young children have been established to eliminate this avoidable indication for liver transplant. A further, very rare, complication with acute hepatitis A is the development of aplastic anemia.

Making the Diagnosis

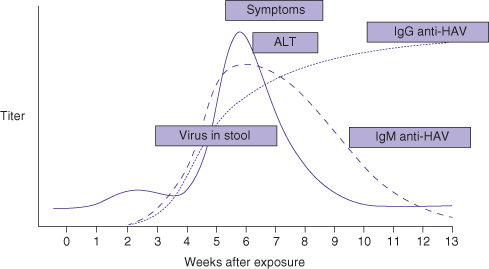

Acute HAV infection cannot be clinically distinguished from other types of acute hepatitis (viral or otherwise). The diagnosis is based on detection of specific antibodies against HAV in serum. Diagnosis of acute infection is made by the detection of IgM anti-HAV antibodies in serum. This test result is positive at the onset of symptoms (Fig. 12.2). IgM anti-HAV antibodies can be detectable at low level up to 1 year after infection. IgG anti-HAV antibodies are often also detectable at the onset of disease and usually remain present for life. Testing for HAV RNA is not widely available and is unnecessary. It is worth noting that in many parts of the world IgM and IgG anti-HAV antibodies are tested together so a specific request for IgM anti-HAV antibodies is necessary to test for acute disease. Relapse with or without cholestasis may recur.

Fig. 12.2 Course of acute HAV infection

(adapted from Hoofnagle JH, DiBisceglie AM. Serologic diagnosis of acute and chronic viral hepatitis. Semin Liver Dis 1991; 11: 73).

Prevention and Therapy

Because HAV is transmitted by the fecal–oral route, adherence to sanitary practices, including heating of foods, hand-washing, and avoidance of unsanitized water, in endemic areas is very effective for prevention of disease.

Vaccination

Several effective and safe vaccines are available for HAV. Live vaccines are available, but inactivated vaccines are highly effective and are used almost exclusively. These include HAVRIX (Smith–Kline Beecham), VAQTA (Merck Sharp Dohme), and TWINRIX (Glaxo Smith–Kline). While HAVRIX and VAQTA are single HAV vaccines, TWINRIX is a combination HAV and HBV vaccine. Inactivated vaccines have high immunogenicity and studies of efficacy report a nearly 100% seroconversion rate after a single course in healthy adults and children (Box 12.2).

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended HAV vaccination for adults with medical, occupational, and lifestyle risk factors (see Table 12.2 for a modified version of this table). Note that vaccine is contraindicated for children less than 12 months old because it is generally ineffective in young infants.

Table 12.2 Groups requiring HAV vaccination

(adapted from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

| Persons with chronic liver disease |

| Persons with close personal contact with an international adoptee from a country of high or intermediate HAV endemicity within first 60 days following arrival of adoptee |

| Persons working in day care, nursing home, or residential care for the mentally challenged |

| Persons traveling to countries with high or intermediate endemicity |

| Any person wishing to obtain immunity |

Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis

Passive immunization with polyclonal serum immunoglobulin can decrease the incidence of HAV infection by 90%. Passive immunity lasts up to 6 months. It should be considered for non-immune individuals who are at risk of HAV exposure or who are allergic to HAV vaccine.

Postexposure Prophylaxis

Immediate postexposure prophylaxis should be considered in individuals (particularly those over age 60 years) who have been exposed to HAV infection and have not been previously immunized. These include individuals who are close personal contacts of an infected person, anyone present in child care centers where HAV is present, or who work with or persons have received food from a food handler with HAV infection. The immediate administration of HAV vaccine or immunoglobulin is equally effective for healthy individuals. For children less than 12 months old, immunocompromised persons, or those with chronic liver disease, immunoglobulin (0.02 mL/kg) is preferred.

Hepatitis B

Virology

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a DNA virus that belongs to the Hepadnaviridae family. The HBV genome has a relaxed, circular, partially double-stranded configuration. Despite its being a DNA virus, replication occurs through an RNA intermediate. There are eight well-characterized genotypes with varying geographic distributions (classified by letters A to H). While HBV replicates primarily in hepatocytes, its presence is found in all body fluids of infected individuals.

Epidemiology

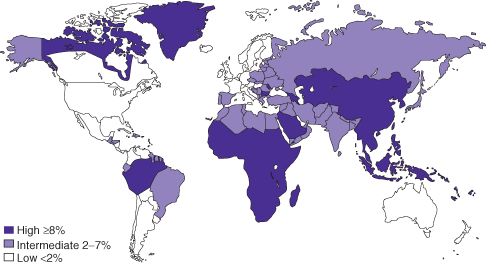

The prevalence of hepatitis B varies markedly around the world (Fig. 12.3). In highly endemic regions such as China, Africa, and Southeast Asia, over 8% of the population are chronically infected, with lifetime risk of infection between 60 and 80%. In these regions, perinatal transmission and horizontal spread amongst children are the major sources of spread leading to chronic infection. Areas of intermediate endemicity (2 to 8% of population chronically infected) include the Middle East, Japan, parts of Southern and Eastern Europe, the former Soviet Union, the Indian subcontinent, and Northern Africa. In these regions, the lifetime risk of infection is 20 to 60%. Spread is similar to that in high endemicity regions. Regions of low prevalence are North America, Western Europe, and parts of South America; sexual contact and injection drug use are the main modes of transmission in these areas.

Fig. 12.3 Worldwide prevalence of hepatitis B

(data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook).

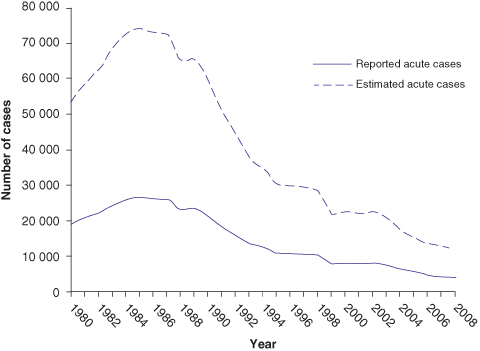

Although hepatitis B virus (HBV DNA) can be detected in most body fluids, it is spread by blood and sexual exposure only. HBV is 100 times as infectious as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and 10 times as infectious as hepatitis C virus. Rates of acute HBV infection are decreasing since the 1990s in the United States, attributed to routine childhood vaccination (Fig. 12.4).

Fig. 12.4 Rates of acute HBV infection in the United States

(data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

Clinical Features

The age at which an individual is infected with HBV is the primary determinant of the clinical outcome (Box 12.3). Infection prior to age 1 year is highly likely to result in chronic infection (see Chapter 13). Infection in adults is likely to cause clinically apparent acute hepatitis B but only 1 to 5% of these individuals become chronically infected, though this is higher in those who are immunosuppressed.

The incubation period of HBV is 1 to 4 months. In adults, the incubation period may be followed by a prodromal serum-sickness-like syndrome, which consists of constitutional symptoms, anorexia, arthralgias, nausea, and right upper quadrant discomfort. However, 70% of individuals infected with HBV as an adult have a subclinical (non-icteric) course and only 30% develop icteric hepatitis. Laboratory testing during this acute phase reveals alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) elevations up to 1000 to 2000 IU/L. In patients who clear the virus, the serum aminotransferases normalize over 1 to 4 months. A serum sickness illness syndrome may accompany (albeit rarely) acute infection with hepatitis, which can include severe generalized arthralgias that last no more than a few weeks.

Fulminant hepatic failure is unusual, occurring in approximately 0.5 to 1% of individuals with acute hepatitis B. Fulminant hepatitis B results from massive immune-mediated destruction of infected hepatocytes and thus affected patients may have no evidence of HBV replication at the time of presentation as they seroconvert to anti-HBs (IgM) very rapidly. The reasons for developing fulminant HBV are not well understood. Fulminant disease should always prompt testing for a superinfection with hepatitis D virus (“delta virus”). “Fulminant” hepatitis may also occur at time of HBeAg seroconversion in someone with a chronic hepatitis B infection.

During recovery from non-fulminant acute hepatitis B, normalization of biochemical tests (ALT and AST) occurs prior to loss of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and the development of anti-HBs antibodies. However, complete eradication of HBV within hepatocytes does not occur and profound immunosuppression (e.g. with rituximab) can lead to reactivation of virus.

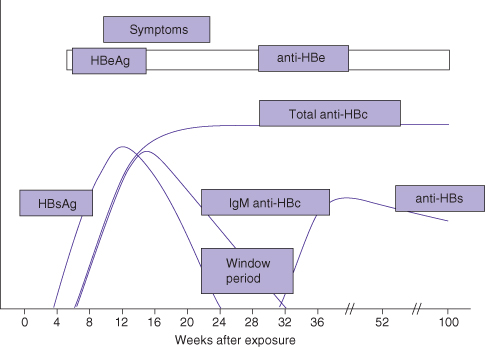

Making the Diagnosis

After infection, hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and HBV DNA become detectable within days. Several weeks later, hepatitis B core antibodies (anti-HBc IgM) and hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) become detectable (Fig. 12.5). In cases where hepatitis B resolves after acute infection, HBsAg disappears after a few weeks. The disappearance of HBsAg is followed by the appearance of antibodies to surface antigen (anti-HBs). However, there may be a “window period” lasting several weeks to months before anti-HBs antibody is detected. During this time, the serologic diagnosis must be made by the detection of anti-HBc IgM antibody. As symptoms resolve, serum ALT improves over several weeks.

Fig. 12.5 Course of acute HBV infection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree