- Cirrhosis may be entirely asymptomatic with no clinical signs.

- Routine laboratory tests that may suggest underlying cirrhosis include: thrombocytopenia, hyperbilirubinemia, and hypoalbuminemia.

- Non-invasive tests (serum panels and transient elastography) are valuable to rule in or rule out cirrhosis.

- Decompensation of cirrhosis is often precipitated by infection, medications, and medical procedures (especially surgery).

- Child–Pugh–Turcotte Score and MELD score are used to assess prognosis in cirrhotic patients regardless of etiology.

- All patients with cirrhosis require screening for esophageal varices and ultrasound surveillance for hepatoma.

- Control of the underlying cause of liver disease may lead to fibrosis regression with “resolution” of cirrhosis; however, risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) persists.

Introduction

The diagnosis of cirrhosis is often first made when a patient develops overt signs of portal hypertension or liver failure; however, cirrhosis will usually have been present in an asymptomatic form for many years prior to the onset of clinical manifestations. Patients with well-compensated cirrhosis may have entirely normal liver synthetic function and no history of complications. Nevertheless, the presence of cirrhosis, even if clinically silent, has important prognostic implications and may significantly affect the course and management of other diseases. Thus a high index of suspicion is needed to recognize cirrhosis. The gold standard for the diagnosis remains liver biopsy with demonstration of discrete nodules surrounded by fibrous tissue. However, clinical and laboratory parameters can also be very suggestive of cirrhosis, as can radiological imaging. Recently, non-invasive assessments of hepatic fibrosis using panels of serum tests and transient elastography have been developed. Both correlate fairly well with liver biopsy, particularly in ruling in or ruling out cirrhosis. The advantages and disadvantages of the different diagnostic modalities will be discussed, followed by a description of the natural history of patients with cirrhosis, both with and without treatment of the underlying liver disease.

Diagnosis

History and Physical Examination in Someone Suspected of Having Cirrhosis

In patients with decompensated cirrhosis, the diagnosis is usually clinically obvious with the presence of ascites/edema, hepatic encephalopathy, and/or jaundice, whereas in well-compensated cirrhosis many patients have no symptoms or signs and therefore a high index of suspicion is necessary to recognize cirrhosis.

Even in patients with previous episodes of hepatic decompensation, the diagnosis may not be clear if neither the patient nor their physician relate their past symptoms to the liver. As a result, all patients with possible liver disease should be asked specifically about past or present:

- ascites

- ankle edema

- jaundice

- GI bleeding (melena, hematemesis)

- encephalopathy

- pruritus

- dyspnea

- non-specific symptoms (fatigue, unexplained weight loss/gain).

Patients may have difficulty distinguishing “abdominal bloating” from ascites. Increasing belt/pant size associated with increasing weight, persistence of the “abdominal swelling,” and ankle edema are suggestive that the abdominal swelling is due to ascites. Patients and even family members may also not recognize jaundice, particularly when it develops slowly over time. However, the onset of darkening of the urine (± staining of underwear) is typically noticed. This is a useful clue to the first appearance of jaundice, which may help clarify if a specific incident occurred that may have precipitated worsening of the clinical condition. Hepatic encephalopathy may also be difficult to appreciate in its early stages. A reversal of the day/night sleep pattern with insomnia at night and daytime somnolence is often the first sign. Subtle impairments in memory and/or executive function should be corroborated by friends or family members. Focal neurological deficits are uncommon with encephalopathy but can occur and reverse with treatment. Persistence of the deficits despite improvement in cognition suggests other etiologies, such as a cerebrovascular event. Pruritus in patients with cirrhosis is most common in biliary diseases but may develop in patients with cirrhosis (or even acute hepatitis). Liver-related pruritus is generalized with no associated rash (although skin markings from excessive scratching may develop) and may be very severe. Pruritus may be exacerbated by certain medications, particularly estrogens and any other medications associated with cholestasis. Dyspnea is not a common symptom of cirrhosis but its presence may have important implications. Patients with ascites who develop shortness of breath may have progressed to hepatic hydrothorax due to defects in the diaphragm with resultant translocation of fluid from the abdomen to the thorax due to the lower intrathoracic pressure. Dyspnea may also signify the presence of hepatopulmonary syndrome1 with intrathoracic right to left shunts. Classically in this setting, patients describe improvement in shortness of breath with lying down, so-called platypnea, thought to be due to a predominance of shunts in the lower lung fields. Dyspnea may also occur in portopulmonary hypertension, a condition in which pulmonary hypertension develops due to primary portal hypertension. Dyspnea may also be unrelated to cirrhosis. Patients may also complain of non-specific symptoms such as fatigue.

Physical examination should include a full examination with a particular focus on signs of chronic liver disease:

- hands: clubbing, Terry’s nails (hypoalbuminemia), palmar erythema, muscle wasting, Dupuytren’s contracture

- head and neck: scleral icterus (best seen in natural sunlight), parotid enlargement, temporal muscle wasting, hepatic fetor

- chest: spider nevi, pleural effusion (hydrothorax usually right-sided)

- cardiac: non-specific findings (low JVP, tachycardia, relative hypotension)

- abdomen: ascites (bulging flanks sensitive test, fluid wave specific test, other tests including shifting dullness), caput medusa (dilated superficial periumbilical veins), liver size (may be large or small), splenomegaly (by percussion using Castell’s test or by palpation), hepatic bruit (may indicate HCC)

- neurological: asterixis, focal deficits

- extremities: pitting edema.

When evaluating patients who have signs of cirrhosis, it is important to consider the context in choosing the tests to perform. If the clinical suspicion for cirrhosis is low, the goal should be to use sensitive tests to rule out cirrhosis, with a move to more specific tests as the diagnosis seems more likely. This is best illustrated with tests for ascites and splenomegaly. Almost all patients with ascites have bulging flanks and thus this test has a high sensitivity, but many patients with bulging flanks are just obese without ascites and therefore this sign is not very specific. In contrast, only patients with fairly tense ascites have a positive fluid wave test meaning that it is not very sensitive, but this finding is present only in patients with peritoneal fluid and therefore is very specific. If a patient does not have bulging flanks, the examination for ascites can stop there, as this is the most sensitive test for the condition. There is no need to assess for shifting dullness or a fluid wave, both of which are more specific but less sensitive. In a patient with a protuberant abdomen, the fluid wave test is very helpful for confirming the presence of ascites. If available, a bedside ultrasound done by an experienced operator is both sensitive and specific. Similarly, Castell’s sign (dullness to percussion in the last intercostal space in the midaxillary line upon inspiration) has a high sensitivity for splenomegaly but modest specificity, while palpation of the spleen is very specific but only possible with significant splenic enlargement and therefore is not very sensitive. Therefore if Castell’s sign, the sensitive test, is negative, there is no need to try to palpate the spleen.

Liver Biopsy

Biopsy remains the gold standard for assessing hepatic fibrosis and diagnosing cirrhosis. Biopsy may also provide information on the etiology of the underlying liver disease. Because of the small size of the sample, liver biopsy specimens are subject to sampling error. Biopsies of at least 2 cm in length (after fixation, i.e. 3–4 cm of fresh tissue) are required for accurate diagnosis. Although very significant fibrosis may be seen on the H&E stain, fibrosis is best appreciated on the Masson trichrome stain, which stains collagen green. The pattern of fibrosis differs by etiology of liver disease, but once cirrhosis is established the patterns may look very similar. Occasionally, if a biopsy is performed in the middle of a large macronodule, it may be difficult to appreciate the degree of fibrosis and cirrhosis may be missed; however, an experienced pathologist should recognize the histologic asymmetry. Alternatively, a superficial biopsy involving mostly liver capsule may overestimate the degree of fibrosis.

Liver biopsy may be performed percutaneously, with or without ultrasound guidance, or via the transjugular route. Transjugular biopsy allows liver tissue to be obtained in patients with impaired coagulation or thrombocytopenia because the biopsy site is within the liver and thus any bleeding will be tamponaded by the surrounding liver. With a percutaneous approach, a tract is made from the liver to the skin and thus if bleeding occurs, it may be very severe. The disadvantages of the transjugular approach are the use of smaller-gauge needles and the need to pass the catheter via the heart, increasing the risk of other complications. A major utility of the transjugular approach is the ability to measure free and wedged hepatic vein pressures to estimate portal pressure. The wedged hepatic vein pressure is an estimate of the transmitted portal vein pressure, similar to the concept of a pulmonary artery pressure approximating the left atrial pressure with a Swan–Ganz catheter. The difference in free and wedged hepatic vein pressure is referred to as the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG). HVPG greater than 5 mmHg indicates the presence of sinusoidal portal hypertension, the most common cause of which is cirrhosis. HVPG also correlates with the risk of complications. HVPG of greater than10 mmHg is associated with development of ascites and increased likelihood of the presence of esophageal varices. Variceal hemorrhage does not occur with HVPG less than 12 mmHg in the setting of cirrhosis. HVPG may underestimate the degree of portal hypertension in patients with cirrhosis if they also have a cause for presinusoidal portal hypertension, such as portal vein thrombosis or granulomatous liver disease (e.g. primary biliary cirrhosis or sarcoidosis). This is because the HVPG focuses only on the gradient across the liver. If the portal pressure is elevated before it reaches the liver (e.g. portal vein thrombosis), the gradient across the liver will still be normal despite the presence of presinusoidal portal hypertension. Similarly, patients with postsinusoidal portal hypertension (e.g. IVC web, heart failure, constrictive pericarditis, pulmonary hypertension) will have elevated free and wedged pressures but a normal gradient (HVPG) across the liver.

Imaging

Cirrhosis may be suggested by the contour and appearance of the liver on abdominal imaging; however, in early cirrhosis, the liver may look entirely normal on all types of imaging. Although fairly specific, imaging is quite insensitive for the diagnosis of cirrhosis. The diagnostic accuracy of imaging is improved if other factors are also taken into account. The presence of signs of portal hypertension suggesting cirrhosis include: splenomegaly, increased portal vein diameter, intra-abdominal varices, and patent umbilical vein.

Non-Invasive Testing

Serum Tests

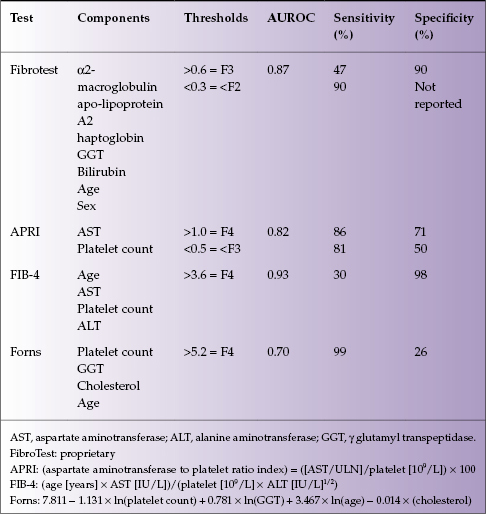

Numerous panels of serum tests have been developed to predict the presence of cirrhosis. Some rely on readily available laboratory tests, while others require specialized testing (see Table 4.1 and Chapter 2).

Table 4.1 Serum tests to diagnose cirrhosis

Most panels have good sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing or excluding cirrhosis but are less predictive for intermediate stages of fibrosis. The tests have been best validated in viral hepatitis (particularly HCV infection) and may not be as accurate in other causes of liver disease. Beyond the panels of tests, routine laboratory parameters can also be helpful in diagnosing cirrhosis. Progressive thrombocytopenia develops in the setting of cirrhosis and portal hypertension due to splenic sequestration and reduced hepatic thrombopoeitin production in advanced disease.2 Patients with cirrhosis also develop a polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia due to high titer antibodies to gut bacteria, which is secondary to portosystemic shunting. In most causes of chronic liver disease, the alanine aminotransferase (ALT) is elevated more than the aspartate aminotransferase (AST); however, as fibrosis progresses, the ratio ALT : AST changes. If the AST is greater than ALT, this is suggestive of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis.

Transient Elastography (TE)

TE uses modified ultrasound to evaluate the speed of propagation of a sound wave through the liver to estimate liver stiffness, which correlates with hepatic fibrosis. TE samples a greater area of the liver than liver biopsy and can be easily performed in the out-patient setting, with immediate results. Liver stiffness continues to increase once cirrhosis is established and may provide prognostic information about the risk of developing complications. TE is inaccurate in the setting of ascites and may be difficult to perform in overweight patients. TE may also be falsely elevated in patients with acute hepatitis.

Natural History

Compensated cirrhosis refers to cirrhosis with preserved liver synthetic function (bilirubin, albumin, and INR) and no portal hypertension (no splenomegaly, varices, ascites) or other complications. Once complications develop, either acutely or chronically, decompensated cirrhosis is diagnosed and this has important prognostic implications. The likelihood of progressing from compensated to decompensated cirrhosis depends on the underlying etiology of liver disease but is also influenced by many other, sometimes external, factors. Patients with well-compensated, stable cirrhosis may develop acute decompensation with systemic insults, particularly infections, surgery/anesthesia, sudden hemorrhage or any cause of profound hypotension (see below), and use of specific medications.

Cirrhosis used to be viewed as an irreversible state; however, recent evidence clearly shows that hepatic fibrosis regresses over time and even cirrhosis can be reversed with removal of the chronic liver insult (e.g. cure of hepatitis C infection, long-term suppression of hepatitis B, abstinence from alcohol, etc.). Regression of fibrosis reduces but does not eliminate the risk of development of complications, such as the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Prognosis

The prognosis of cirrhosis is highly variable, depending on the etiology of liver disease, presence of complications, and comorbid diseases. Predictive models have been developed to help estimate the survival of patients with cirrhosis.

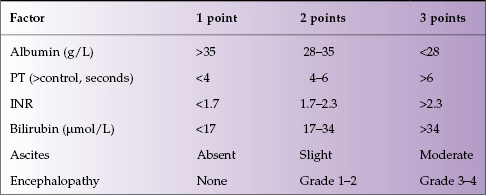

Child–Turcotte–Pugh Score

The Child–Turcotte score was originally designed to predict outcome in patients undergoing portocaval shunting in the presence of cirrhosis and included: albumin, bilirubin, ascites, encephalopathy, and nutritional status. The score was modified for patients undergoing non-shunt surgery (Child–Pugh; Table 4.2). Nutritional status was removed as a parameter and the prothrombin time/INR was added. The score only applies to patients with cirrhosis. The minimum score is 5 (i.e. 1 point for each factor assessed).

- Grade A (well compensated): score of 5–6

- Grade B (significant functional compromise): score of 7–9

- Grade C (decompensated disease): score of 10–15.

Table 4.2 Child–Pugh score

The Child–Pugh grade is predictive of 1- and 2-year survival:

- Grade A: 100% 1-year, 85% 2-year survival

- Grade B: 80% 1-year, 60% 2-year survival

- Grade C: 45% 1-year, 35% 2-year survival.

The Child–Pugh score is also predictive of mortality with abdominal surgery: Grade A 10%, Grade B 30%, and Grade C 82%.

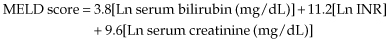

Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD)

The MELD score was developed using regression modeling based on the 3-month survival of patients post-TIPS (transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting) insertion. MELD score includes bilirubin, INR, and creatinine in the following formula:

The original version of the MELD score included points for the etiology of liver disease; however, this factor has now been removed. MELD is designed to have a minimum value of 3. Because logarithms are used, values below 1.0 are not permitted to avoid negative numbers. Hence the minimum values to be included are bilirubin 1 mg/dL, INR 1.0, and creatinine 1 mg/dL. This is often relevant for patients with early decompensation as creatinine values may be below 1.0 mg/dL because of low muscle mass. In such cases, MELD scores should be calculated using a creatinine of 1 mg/dL.

MELD has proven to be of prognostic utility in many circumstances and for most chronic liver diseases. It is now used for organ allocation on the liver transplant waiting list in the USA. Minimal MELD score for transplant is usually around 15. This is based on the fact that at a MELD of 15, the 1-year survival probabilities with and without a transplant become equivalent (80 vs. 81%). With lower MELD scores survival without a transplant is greater than with a transplant and for higher MELD scores transplantation improves survival.

Modifications to MELD.

Modifications have been proposed including: inclusion of serum sodium concentration, serum albumin concentration, and different weighting of the bilirubin, INR, and creatinine. These modifications may ultimately be adopted for organ allocation. The MELD score is modified if HCC is present because patients may have poor survival based on the presence of HCC despite relatively preserved liver synthetic function, and thus low MELD scores. Very early tumors are not given extra MELD points. Tumors of 2–5 cm or two to three lesions of less than 3 cm are assigned a MELD score of 24 (15% mortality at 3 months) and the score increases every 3 months equivalent to an increase of 10% risk of mortality. The number of MELD points at each interval differs based on the severity of disease at the time of evaluation because the MELD score is not linear, with small absolute differences in MELD score predicting greater changes in mortality rate at higher baseline MELD scores (e.g. a change of MELD from 9 to 11 is of less significance than from 24 to 26).

MELD has also been validated as a predictor of survival in the following conditions:

- alcoholic hepatitis

- hepatorenal syndrome (MELD >20 predicts worse survival)

- acute variceal hemorrhage in cirrhotic patients

- sepsis in cirrhotic patients as long as unrelated to spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

- abdominal, orthopedic, and cardiac surgery in known cirrhotic patients.

Clinical Stages of Cirrhosis: Prognosis

The Baveno classification system categorizes patients with cirrhosis based on clinical factors only, which have proven to be useful for prognostication at the population level.3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree