- Nowadays, most adult patients with cholestatic liver disease are first diagnosed when asymptomatic; this is not the case for children.

- In adults, testing for antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA) can rapidly diagnose primary biliary cirrhosis without the need for further investigation, except in the appropriate context.

- Cholangiography by MRI is indicated if AMA negative or in those with pre-existing risk factors for primary sclerosing cholangitis, such as inflammatory bowel disease.

- Early surgery in infants with biliary atresia is important in order to derive greatest benefit from biliary surgery; this underscores the need to rapidly investigate jaundice in babies.

Introduction

Cholestasis arises whenever impairment of hepatobiliary excretion occurs and normal biliary constituents appear in the circulation. If marked, jaundice and pruritus are notable, but, when milder, abnormal liver biochemistry and non-specific symptoms such as fatigue may be the only evidence. Generalized pruritus can occur at any stage of cholestatic liver disease. In addition to the systemic presence of biliary constituents, tissue cholestasis is seen at the level of hepatocytes, with retained bile acids proving toxic to the liver.1,2

The etiologies of cholestasis can be found at either the level of the hepatocyte, the small bile duct, or the large bile duct, and can be considered to be either acute and self-limiting or chronic, with irreversible duct loss and/or progressive biliary fibrosis. Mechanisms of injury include toxins, genetic defects, inflammation, immune mediated or obstruction, although some conditions are characterized by more than one process.

The characteristic biochemical features of chronic cholestasis are an elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP), or, more reliably in children, by elevation in γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT). Transaminases may be elevated, but generally cholestasis is characterized by a ratio of ALP : ALT (alanine transaminase) of greater than 3. In very acute cholestasis, such as that sometimes seen in pregnancy, elevated transaminases are predominant. Jaundice in cholestatic liver diseases may be due to direct biliary obstruction, hepatocyte injury and subsequent failure to excrete bilirubin, or end-stage liver disease.

Differential Diagnosis

Chronic cholestatic syndromes are prevalent but have a lower annual incidence than acute processes such as drug toxicity, gallstone disease, or severe hepatitis with consequent cholestasis. Traditionally, “chronic” is applied when the pathology appears to persist for greater than 6 months. In childhood, however, cholestatic syndromes represent the most common class of liver disease. Pediatric illnesses within this umbrella include biliary atresia (BA), Alagille syndrome (ALGS), and the inherited biliary transporter disorders (previously collectively labeled as the progressive familial intrahepatic cholestatic (PFIC) syndromes). In adults, chronic cholestatic liver disease is largely restricted to two inflammatory syndromes. Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) a classic autoimmune disease, and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), an autoinflammatory disease, commonly associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Other etiologies can give rise to secondary biliary disease, which include chronic biliary obstruction and secondary cholangiopathies consequent to ischemia, infection, residual drug toxicity, inherited biliary abnormalities, or inflammation.

Pediatric

In childhood the distinction between acute and chronic disease is less valuable, compared to a consideration of the age at presentation (see Chapter 3).

Biliary Atresia.

BA is the most common cause of end-stage liver disease and liver transplantation in children. It is a progressive sclerosing inflammatory process of extrahepatic and intrahepatic bile ducts causing complete biliary obstruction in the first 3 months of life. It has an incidence of 1 in 10 000 live births. The etiology is unknown but postulated to be an immune-mediated perinatal insult in 80% of cases and syndromic in 20%, in which case it is associated with other congenital anomalies such as situs inversus, cardiac defects, malrotation, and polysplenia. BA is uniformly fatal unless a Kasai portoenterostomy is rapidly performed, in which a Roux-en-y jejunostomy is formed to establish bile drainage from the hilar plate. This surgery has the best outcomes if performed within the first 60 days of life. Nevertheless, even in children who do establish biliary flow, there is progressive hepatic fibrosis. Approximately 50% of all children with BA undergo liver transplantation by the age of 2 years and more than 90% of young adults with BA who have their native liver have hepatic fibrosis.3

Alagille Syndrome.

ALGS is the most common inherited cause of conjugated hyperbilirubinemia in the neonatal period. It is a multisystem, autosomal dominant disorder characterized by cholestatic liver disease and bile duct paucity on liver biopsy, congenital cardiac defects, typically peripheral pulmonary stenosis, renal anomalies, vascular abnormalities, characteristic facies (broad forehead, deep-set eyes, and a pointed chin), posterior embryotoxon of the eye on slip-lamp examination, and skeletal anomalies, commonly butterfly vertebrae. In the majority of patients (>93%) a mutation in JAGGED1 can be identified whilst a smaller number of ALGS individuals have mutations in NOTCH2. Mutations are inherited in 40% and de novo in the remainder.4

Progressive Familial Intrahepatic Cholestasis Syndromes.

This group of three biliary transport disorders that were previously categorized as PFIC1, PFIC2, and PFIC3, are now better described by their molecular terminology.

- PFIC1/FIC1 deficiency: this is an autosomal recessive condition that presents with cholestasis in early childhood. It is caused by mutations in ATPB81, encoding an aminophospholipid flippase which is widely expressed throughout the body. As a consequence, in addition to severe pruritus, it is manifest by failure to thrive, diarrhea, sensorineural hearing loss, and pancreatic dysfunction.

- PFIC2/BSEP deficiency: the presentation is similar to FIC1 deficiency though it is caused by mutations in another canalicular transporter gene, ABCB11. However, the bile salt export pump is only expressed in the liver and therefore there are no extrahepatic manifestations. It is characterized by cholestasis, gallstones, and a higher incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma, which is otherwise very unusual in childhood.

- PFIC3/MDR3 deficiency: this condition is also inherited as an autosomal recessive trait and is a defect of biliary phospholipid secretion. Although it may present in early life with cholestasis, it has a broader range of presentations, including recurrent choledocholithiasis in older children and adults, and some cases of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy.

- Benign recurrent cholestasis: this causes episodic cholestasis (rarely progressive) and is associated with ATP8B1 and ABCB11 mutations.

Miscellaneous.

Immune-mediated processes such as PSC also present in older children, with some similarity to adults. Of note, in children with autoimmune hepatitis, upwards of 50% of them will have a cholangiopathy; this is often described as an “overlap” syndrome, termed autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis. Metabolic liver diseases such as α1-antitrypsin deficiency and cystic fibrosis-related liver disease may present with cholestasis in early childhood, although these are not classically considered cholestatic diseases.

Adults

Primary Biliary Cirrhosis.

As the commonest adult chronic cholestatic liver disease, PBC is an archetypal autoimmune biliary disease, in which the overwhelming majority of patients are women in middle age who have circulating antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA). One in 1000 Caucasian women over the age of 40 are estimated to have the disease. Histologically, disease is evident as a granulomatous lymphocytic cholangitis, in which small bile duct loss progresses alongside an interface hepatitis. Biliary cirrhosis is the end result. Clinically, presentation is usually asymptomatic and is identified by blood work alone, but symptoms of pruritus in particular may be evident.5

Sclerosing Cholangitis.

PSC is a progressive inflammatory disease of the large bile ducts, which is more common in men. It is frequently associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Its prevalence is probably about half that of PBC. It is a disease that can affect children as well as adults, although typically patients present with symptoms in their 40s. With incidental screening, the age at diagnosis is ostensibly falling. The disease is usually diagnosed by imaging criteria (cholangiography by MRI or endoscopically); liver biopsy changes can be patchy and is therefore not usually needed. Histologically, a fibro-obliterative process may be seen surrounding larger bile ducts, with so-called “onion skin” fibrosis. Disease is predominantly driven by this obstruction to biliary drainage, although, as with PBC, a component of liver injury is from an interface hepatitis. Patients are commonly asymptomatic upon diagnosis, which is a result of screening biochemistry in “at-risk” populations. As disease progresses to secondary biliary cirrhosis, cholangitis, portal hypertension, and liver failure are common.6

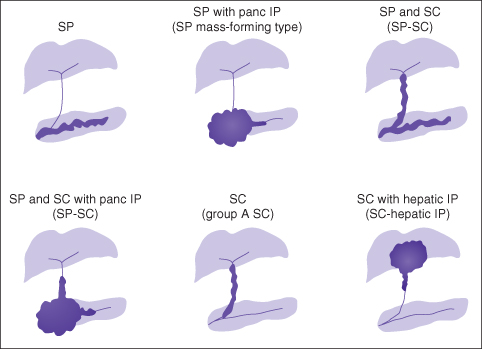

Secondary sclerosing cholangitis is the term used when a recognized etiology for large duct cholangiopathy can be identified, and occurs because there appears to be a common pathway to biliary injury such that a variety of insults cause sclerosing cholangitis.7 Many secondary causes are recognized including, but not limited to, autoimmune pancreatitis, biliary ischemia (arterial or secondary to chronic portal vein thrombosis), an infected choledochal cyst, and recurrent intrahepatic choledocholithiasis or infective cholangitis, particularly in patients with various immunodeficiencies. Before the label primary is applied to patients, clinicians should assiduously consider secondary etiologies, in particular IgG4-associated autoimmune pancreatitis, a disease that is multisystem and exquisitely sensitive to steroids, unlike PSC (Fig. 20.1).

Fig. 20.1 A spectrum of IgG4-associated sclerosing cholangitis. IP, idiopathic pancreatitis; SC, sclerosing cholangitis; SP, sclerosing pancreatitis.

From: Björnsson E, Chari ST, Smyrk TC, Lindor K. Immunoglobulin G4 associated cholangitis: description of an emerging clinical entity based on review of the literature. Reproduced from Björnsson et al. Hepatology 2007; 45: 1547–54 with permission from VG Wort.

Idiopathic Ductopenia.

Histologically, the only positive finding is of small bile duct loss. The cholestatic disease course is usually but not always progressive. Drug exposure must be carefully excluded as should paraneoplastic syndromes, especially those of lymphoma. Overall, this rare syndrome is likely a collection of diseases including genetic triggers and unidentified toxin exposure.

Adult Presentations of Inherited Disease.

Benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis is usually a variant of PFIC2 (low GGT cholestasis). Patients may experience recurrent episodes of symptomatically intense, histologically bland cholestasis, which is sometimes triggered by infection or medication. MDR3 (PFIC3) mutations can also have a varied presentation in adulthood, including cryptogenic biliary cirrhosis, recurrent intrahepatic choledocholithiasis, and cholestasis of pregnancy. Pediatric patients with ALGS and biliary atresia successfully managed by Kasai portoenterostomy may transition to adult care. Those with ductal plate malformations such as Caroli disease, in addition to having portal hypertension, can have cholestatic disease as well as renal disease; either polycystic or medullary sponge kidneys may be present.

Miscellaneous.

These include chronic graft versus host disease following bone marrow transplant, any severe hepatitis including autoimmune hepatitis, resolving hepatitis A, hepatitis E, or EBV infection, hepatic infiltration including sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, tuberculosis, any granulomatous liver injury, and malignancies such as lymphoma and adenocarcinoma; severe recurrent hepatitis B or C post-liver transplant and post-transplant chronic rejection can also give rise to chronic cholestasis.

Making the Diagnosis

Presentation

Adult Perspective

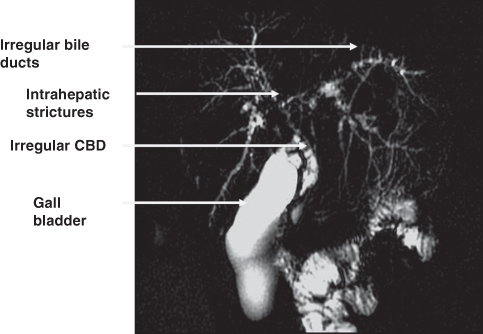

In adult practice, presentation can be asymptomatic or symptomatic. Asymptomatic presentations are increasingly common. In adults, the usual observation is a disproportionate elevation in ALP. GGT is usually also elevated; although GGT is a very sensitive biochemical marker of liver injury, the majority of patients with an elevated GGT do not have a cholestatic liver disease. Additionally, fatty liver can present with an isolated elevation in ALP. The utility of GGT is of course the exact opposite in children, where ALP is not very helpful because it is also produced in bone. Other asymptomatic presentations occur when patients with associated autoimmune diseases are specifically screened by their clinicians for either PBC or PSC (e.g. in those with Sjögren syndrome, scleroderma, and inflammatory bowel disease). When symptomatic, patients with cholestatic liver disease may present with jaundice (but this is increasingly uncommon as dark urine and pale stools are usually recognized before scleral icterus), pruritus (a broad differential, but this is a specific symptom of cholestasis), or fatigue (a very non-specific symptom). Patients with PBC commonly complain of eye, mouth, or vaginal dryness. More often than not this reflects a non-specific sicca complex syndrome, as opposed to primary Sjögren syndrome. Cholangitis (which is clinically manifested as right upper quadrant pain and fever) is a medical emergency regardless of etiology and prompt treatment with antibiotics trumps investigation initially. It is not a feature of small bile duct disease, and indeed it should be noted that de novo cholangitis in PSC is uncommon, usually only occurring after there has been an intervention such as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). This may not be the case in some secondary forms of cholangitis, for example portal biliopathy (Fig. 20.2). Additionally, an elevated white cell count whilst common is not universal; patients with severe cholangitis can have a normal white blood cell count. A dull ache over the liver is not infrequently noted by women with PBC, and perhaps this is just a reflection of the hepatomegaly of cholestasis.

Fig. 20.2 Portal biliopathy at magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRC). Definitive therapy is retroperitoneal splenorenal anastomosis. CBD, common bile duct.

Pediatric Perspective

Cholestatic liver disease in children is invariably symptomatic. Infants will typically present with jaundice and conjugated hyperbilirubinemia. The GGT is an important discriminator between different groups of diseases. Infants with BA and ALGS present with high-GGT cholestasis. They can be further differentiated by the presence of other characteristic congenital anomalies in ALGS. However, since variable expression is a hallmark of ALGS, extrahepatic involvement may be subtle and other investigations are required (see below). Children with BA progress to end-stage liver disease within a few months of life without surgical intervention. Children with ALGS and cholestatic liver disease usually develop intense pruritus and xanthomas (Plate 20.1) in the first few years of life. The liver disease of ALGS does not have onset outside early childhood, though it may progress or improve with time. Infants with FIC1 and BSEP deficiency present with low-GGT cholestasis and usually present outside the neonatal period but in the first 2 years of life with intense pruritus. They do not have xanthomas.

Investigations

Investigation is aimed at diagnosis, estimating disease severity, and looking for associated complications (Box 20.1). In addition to a pertinent and comprehensive history from the patient (which must include family history of autoimmunity/biliary disease and a careful drug history), thorough clinical examination remains important, even if nowadays no abnormal physical findings are likely to be evident. Findings may not be specific but patients may be jaundiced, and/or have hepatomegaly and splenomegaly, as well as other signs of chronic liver disease/portal hypertension, such as spider telangiectasia, ascites, and muscle wasting. Occasionally, overt skin damage from chronic itching can be evident, as well as skin xanthelasma and xanthomas. Undue lymphadenopathy should prompt one to consider lymphoma.