- The initial diagnosis of liver disease begins with a complete history, physical examination, and simple liver biochemical blood tests.

- Liver biochemistry determines the pattern of liver enzyme elevation—hepatocellular versus cholestatic liver disease.

- An accurate assessment of severity of liver disease is important to determine prognosis and management.

- The degree of liver dysfunction is determined primarily by blood work, such as total bilirubin and INR.

- Liver biopsy may be used to make an accurate diagnosis and remains the gold standard to stage the degree of hepatic fibrosis in those with chronic liver disease.

- Child–Turcotte–Pugh score and the Model for End-stage Liver Disease score offer the best estimate of survival for patients with cirrhosis (see Chapter 4).

- Abdominal ultrasound is best used to identify space-occupying lesions and evaluate venous supply and drainage—but is not reliable to diagnose cirrhosis.

- Non-invasive laboratory testing, including FibroTest and FibroScan, may reduce the need for biopsy to confirm cirrhosis, but neither have been validated for all etiologies of liver disease.

Introduction

The initial diagnosis and workup of liver disease begins with a complete patient history (including thorough review of prescribed and non-prescribed drug use), physical examination, and simple liver biochemical blood tests. Accurate assessment of disease severity depends, in part, on the possible cause of liver disease. For example, the prognosis of chronic viral hepatitis and alcoholic liver disease depend on the degree of fibrosis and inflammation on liver biopsy, whereas biliary disease severity can be determined by simple blood tests.

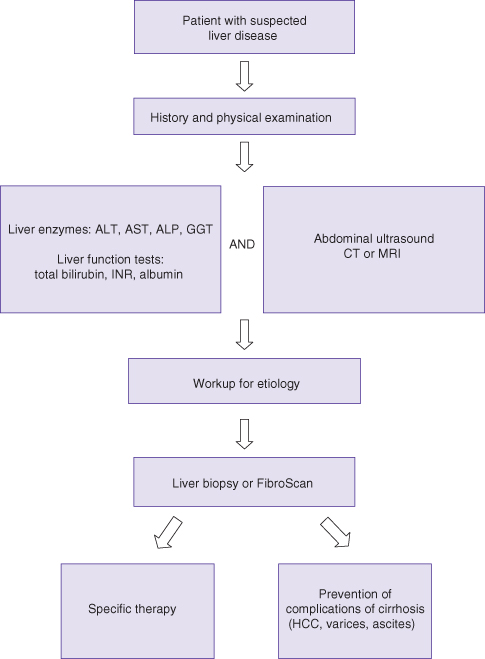

The severity of the underlying liver disease indicates prognosis and determines the timing for treatment. Patients with cirrhosis require prompt attention and intervention, if a treatment is indeed available. A general approach to assessment of liver disease is illustrated in Fig. 2.1.

History

Clues as to the presence of liver disease and its etiology may be found in a patient’s complete medical history:

- the ethnicity and country of birth (which may be risk factors for viral hepatitis);

- risk factors for viral liver disease such as blood transfusion, injection drug use, sexual promiscuity, or exposure to improperly sterilized needles (e.g. tattoos);

- a family history of viral hepatitis, cirrhosis, and liver cancer is important;

- genetic risks for liver disease, such as Wilson disease and hereditary hemochromatosis;

- alcohol consumption—total daily amount and the pattern of drinking as determined by the CAGE questionnaire are helpful features in distinguishing alcoholic liver disease from non-alcoholic fatty liver disease;

- a careful medication history, including all prescription, over-the-counter, and herbal medications, is key to the diagnosis of drug-induced liver injury (DILI);

- medical comorbidities, including diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, are associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with or without cirrhosis;

- a personal or family history of autoimmune disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis, thyroiditis, and inflammatory bowel disease, may raise suspicion for autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC), and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC);

- history of pruritus—typical in those with cholestatic liver disease;

- onset of symptoms—jaundice, dark urine, increasing abdominal girth, leg swelling, fever, or acute confusion are all worrisome features both in those with acute liver disease as well as for those with known chronic liver disease:

- dark urine implies conjugated hyperbilirubinemia and indicates some degree of hepatic or biliary disease

- worsening of jaundice and dark urine/pale stools suggests complete biliary obstruction;

- dark urine implies conjugated hyperbilirubinemia and indicates some degree of hepatic or biliary disease

- melena and/or hematemesis caused by gastroesophageal varices indicates a poor prognosis, since upper gastrointestinal bleeding is associated with high mortality;

- right upper quadrant abdominal pain may be present in biliary diseases such as acute cholecystitis but also may be present in patients with chronic liver disease (e.g. PSC).

Clues from the history that may indicate the cause of liver disease are summarized in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1 Clues to diagnosis of liver disease on history

| Disease | Clues in patient history/symptoms |

| Hepatitis B | Born in an endemic area (SE Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, Eastern Europe) Family history of hepatitis B, cirrhosis, or liver cancer Traumatic sexual activity |

| Hepatitis C | Previous or current injection drug use/tattoos Born in area where exposure to non-sterile procedures common Receipt of an i.v. blood product (date needed) |

| Hepatitis A/E | Travel to endemic area (Asia, Indian subcontinent, Latin America) Exposure to contaminated food, water, raw shellfish |

| Alcohol-related liver disease | Long-term alcohol consumption or binge drinking: women >2 drinks/day; men >4 drinks/day Positive CAGE questionnaire* (>1 positive response in men) |

| Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease | Diabetes mellitus/hypertension/dyslipidemia Obesity/sedentary lifestyle/poor dietary habits |

| Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) | New medication exposure within last 12 weeks No known pre-existing liver disease |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | Personal or family history of autoimmune disease |

| Hereditary hemochromatosis | Family history of diabetes mellitus/arthralgias/cardiomyopathy |

| Wilson disease | Family history of cirrhosis, hepatitis, liver failure Personal or family history of psychiatric disease |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | Fatigue/pruritus/hypercholesterolemia Personal or family history of autoimmune disease |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | Jaundice and/or pruritus/right upper quadrant pain Recurrent episodes of “cholangitis” |

*CAGE questionnaire: Has anyone asked you to Cut down on drinking alcohol?; Do you feel Annoyed when asked to cut down?; Do you feel Guilty about your drinking?; Do you need an Eye-opener?

Physical Examination in Patients with Suspected Liver Disease

Physical examination in patients with suspected liver disease is as follows.

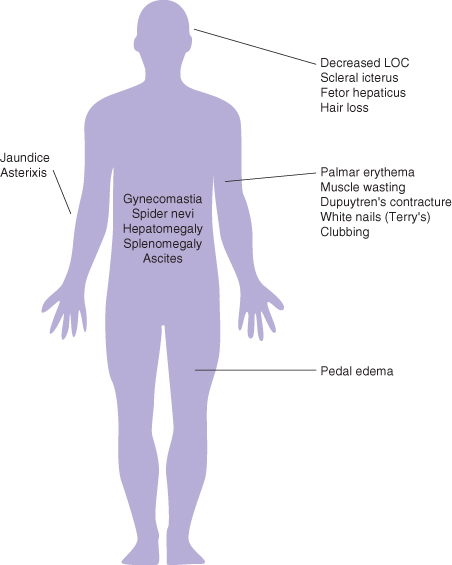

- Scleral icterus is only visible when total bilirubin levels rise above two to three times the upper limit of normal.

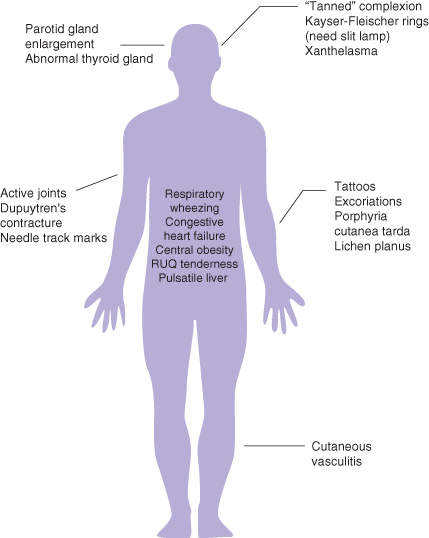

- Needle track marks indicate prior injection drug use, which is a risk factor for viral hepatitis.

- Porphyria cutanea tarda, lichen planus, and cutaneous vasculitis represent extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis C.

- Spider nevi (confined to upper body) and/or easy bruising are signs of chronic liver disease.

- Signs of congestive heart failure and an enlarged, pulsatile liver suggest a congestive hepatopathy.

- General inspection of the abdomen may reveal central obesity, abdominal masses, striae, abdominal wall collateral vessels, umbilical hernia, and ascites.

- When palpating the abdomen, particular attention should be paid to the liver span and consistency of the liver edge.

- Common causes of hepatomegaly include fatty liver and other infiltrative disorders. A normal liver edge is soft and smooth; a hard, liver edge may be palpated in cirrhosis, amyloidosis or liver metastases.

- Splenomegaly is commonly detected in patients with portal hypertension due to cirrhosis or portal vein thrombosis.

- Auscultation may reveal peritoneal friction rubs or bruits over the liver in patients with alcoholic hepatitis, liver metastases, or hepatocellular carcinoma.

- The presence of ascites—bulging flanks, shifting dullness, or a positive fluid wave test—is an indicator of severe portal hypertension. Ascites can be confirmed with a bedside abdominal ultrasound.

- Flapping tremor.

- Orientation and level of consciousness (LOC): patients with overt hepatic encephalopathy and who have decreased LOC may require monitoring in the ICU setting. Of note, encephalopathic patients in acute liver failure who also develop jaundice are unlikely to survive without a liver transplant.

- Peripheral neuropathy: alcoholic and/or diabetic.

Key findings of chronic liver disease on physical examination are found in Fig. 2.2, while Fig. 2.3 illustrates clues to the etiology of liver disease based on the physical examination.

Fig. 2.3 Clues on physical examination for etiology of liver disease. PBC, primary biliary cirrhosis; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.

Laboratory Tests

Measurement of liver enzymes is relatively sensitive but not entirely specific for liver disease. For example, elevated aminotransferases may be found in cardiac or musculoskeletal disease. However, entirely normal aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) values may be present in patient with well-documented cirrhosis. The degree of liver enzyme elevation is generally not predictive of disease severity, whereas abnormalities in the markers of liver synthetic function, such as albumin, total bilirubin, and the international normalized ratio (INR), do indicate the severity of liver dysfunction.

AST, ALT, ALP (Alkaline Phosphatase), and GGT (γ-Glutamine Transaminase)

Elevated aminotransferases/transaminases are a sensitive indicator of hepatocellular damage. They are important in monitoring liver disease activity and response to treatment (e.g. autoimmune hepatitis). However, a one-time elevation in ALT in patients with chronic hepatitis B or C is unreliable and cannot be used to determine need for antiviral therapy. The trend in ALT levels is much more useful in ascertaining which patients with chronic hepatitis (B or C) may require therapy. It has been recommended that the upper limit of normal for ALT be reduced from 40 IU/L to 30 IU/L in men and 19 IU/L in women.

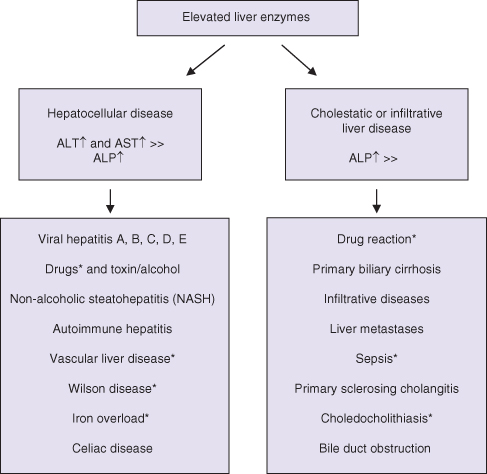

The pattern of liver enzyme elevation is typically classified as hepatocellular (AST and ALT elevation > alkaline phosphatase (ALP) elevation) or cholestatic (ALP elevation > AST or ALT elevation), as illustrated in Fig. 2.4. Elevation of GGT is really too non-specific to be of clinical help in formulating a diagnosis. GGT is rarely a helpful test as it may be elevated in all forms of liver disease or as a result of drug induction (e.g. antiepileptics).

Fig. 2.4 Patterns of liver enzyme elevation. *Can be associated with both hepatocellular and cholestatic features (mixed).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree