- Early complications after liver transplantation include bleeding, bile leaks, anastomotic and non-anastomotic biliary strictures, and hepatic artery or portal vein thrombosis (seen most often in children).

- Acute cellular rejection occurs in about 20% of liver transplant recipients, usually within the first 3 postoperative months; its diagnosis requires a liver biopsy and it usually resolves with increased immunosuppression.

- Liver transplant recipients are at increased risk of any type of infection, CMV infection/disease being among the most important ones.

- Many malignancies are more frequent in liver transplant recipients than in the normal population; liver transplant recipients, especially children who acquire EBV post transplant, are at high risk of developing EBV-associated lymphoma (post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder).

- Calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine A, tacrolimus) form the backbone of maintenance immunosuppression and are, among other side effects, associated with nephrotoxicity.

- Obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance/diabetes are common in liver transplant recipients; the risk for fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events is therefore threefold increased compared to a normal population.

- The underlying disease may recur with varying frequency after liver transplantation and may impact on survival outcome, such as recurrent hepatitis C.

- Internist/family physician and transplant hepatologist share the long-term care for the liver transplant recipient; the internist/family physician is best qualified to manage cardiovascular risk factors and many conditions common in the non-transplant population, which may occur also in the liver transplant recipient (including respective screening and preventative measures); the transplant hepatologist’s expertise is best utilized to manage immunosuppression, recurrent disease, and other directly graft-related issues.

- In the pediatric population, the age at transplantation can lead to many long-term issues with regard to social and intellectual functioning.

Introduction

Complications of liver transplantation are manifold. They not only include surgical issues that typically manifest in the early postoperative period, such as bleeding, bile leaks, or hepatic artery thrombosis, but also allograft rejection, and complications intrinsic to long-term immunosuppression (such as infections and malignancies). They also include renal dysfunction and metabolic long-term sequelae such as obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and diabetes, which translate into an increased risk for cardiovascular diseases. Recurrence of the underlying liver disease may, in a strict sense, not be regarded as a complication of liver transplantation, but adds to the long-term morbidity and mortality post transplant and is briefly discussed at the end of this chapter. In the pediatric population, depending on the age at transplantation, issues related to education and socialization need to be addressed.

Early Postoperative Period

Early postoperative complications mostly occur during the initial hospital stay and are dealt with by the multidisciplinary transplant team. A detailed review of these complications is beyond the scope of this chapter. However, a few are worth mentioning because they may pertain to the longer-term course and therefore be of importance for the internists or family physicians involved in the long-term care of liver transplant recipients (Table 11.1).

Table 11.1 Early postoperative complications of potential long-term importance

| Event/complication | Long-term sequelae |

| Anastomotic biliary stricture | Need for repeated endoscopic or percutaneous intervention or re-operation |

| Hepatic artery malperfusion (due to stenosis, subacute thrombosis, or transplant with a liver donated after cardiac death) | Ischemic type diffuse intrahepatic biliary structuring, cholangitis, biliary liver abscess, secondary biliary cirrhosis, and graft failure |

Usually, graft function resumes immediately with normalization of coagulation parameters and improvement of bilirubin within the first couple of days, that is, return of liver function to normal. Delayed graft function, primary non-function (i.e. when the graft never regains function), and hepatic artery thrombosis are rare but serious conditions, which may require early re-transplantation. As with any large hepatobiliary surgery, bleeding and bile leaks can occur and may require surgical re-intervention. Bile duct problems occur in 10–20% of cases. Early bile leaks are secondary to ischemia, sepsis, or rarely to severe rejection. Anastomotic biliary strictures may develop and require endoscopic intervention (dilatation and/or stenting) or re-operation. Any compromised arterial blood supply to the graft may lead to ischemic type diffuse intrahepatic biliary stricturing, which is difficult to manage, often results in secondary biliary cirrhosis (with associated cholangitis and/or abscess formation), and may require late re-transplantation.

Most patients are extubated within 24 hours post transplant (and some immediately after surgery). Some recipients, particularly when severely deconditioned prior to transplant, or those with delayed graft function, large pleural effusions, pulmonary infiltrates, and/or diaphragmatic dysfunction/paralysis, may require extended ventilator support (with the risk of acquiring a ventilator-associated pneumonia). Resolution of pre-existing severe encephalopathy, particularly as seen in fulminant hepatic failure, often requires prolonged ICU care. Confusion and seizures related to metabolic disturbances and the calcineurin inhibitors used for immunosuppression may occur. Renal dysfunction, fluid overload requiring diuretics, and temporary renal replacement therapy are not uncommon complications. Typically, these issues have all resolved or are medically controlled by the time the patient is discharged.

Rejection

Having an enormous functional reserve and a unique regeneration potential, the liver is a privileged organ for transplantation. Thus, destruction of hepatocytes by rejection will not affect long-term outcome, provided the rejection process can be stopped, which is almost always possible with today’s medications. It is therefore safer to err on the side of under-immunosuppression and risk rejection, than over-immunosuppress and run the risk of life-threatening infections and, in the long-term, malignancies (Table 11.2).

Table 11.2 Balance of immunosuppression

| Immunosuppression level | Sequelae |

| Too little immunosuppression | Acute cellular rejection |

| Too much immunosuppression | Infections (bacterial, viral, fungal) |

| Malignancies in general, especially: EBV-associated post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder Non-melanoma skin cancers |

Acute cellular rejection (ACR) develops in about 20% of liver transplant recipients, most frequently in the first 3 months after transplantation. Late ACR, that is rejection episodes occurring more than 3 months post transplant, is usually attributable to under-immunosuppression caused by compliance issues, therapeutic misadventures (drug interactions, see below), or drug malabsorption (nausea/vomiting, diarrhea). ACR is often clinically asymptomatic but can be accompanied by a low-grade temperature, and some malaise and right upper quadrant discomfort. ACR is accompanied by (and needs to be considered when routine blood work shows) rising liver enzymes in an entirely non-specific pattern that can either be hepatitic (high serum concentrations of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT)), or cholestatic (high bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase (ALP)), or mixed. The clinical suspicion of ACR, therefore, requires confirmation by liver biopsy. This typically shows a mixed cellular periportal inflammation with mononuclear cells, neutrophils and eosinophils, bile duct injury, and endothelialitis, that is (sub)endothelial inflammatory changes in small portal and/or central veins. Using the Banff rejection activity index (RAI, maximum 9 points),1 ACR is graded into mild (RAI ≤ 3), moderate (RAI 4–6), and severe (RAI ≥ 7). Mild ACR usually responds to increased maintenance immunosuppression alone. Moderate and severe ACR, typically resolve with i.v. bolus steroids (500 mg methylprednisolone i.v. daily for 3 consecutive days), followed by a gradual oral prednisone taper. Steroid-resistant rejection requiring therapy with an antilymphocyte globulin preparation has become extremely rare.

Failure of ACR to respond to immunosuppressive therapy, in conjunction with other ill-defined mechanisms, may result in chronic ductopenic rejection (CDR). CDR leads to obliteration of medium-sized arteries (that are typically not sampled by liver biopsy) by lipid laden, hyperplastic endothelial cells (foamy cell obliterative arteriopathy). This results in disappearance of small interlobular bile ducts and eventually evolves into biliary cirrhosis. CDR causes late graft loss, that is, the need for re-transplantation or death, in 2–5% of all liver transplanted recipients.

Side Effects of Immunosuppression

Lifelong immunosuppression to prevent rejection is required in all liver transplant recipients. There are general complications associated with the extent and duration of immunosuppression per se, such as infections and malignancies, and the specific side effects associated with each individual immunosuppressive drug.

General

Infectious complications are the single most important cause of mortality early after liver transplantation. The risk of infection is associated with surgical problems, for example bile leaks, as well as the degree of immunosuppression, and endogenous/exogenous exposure to pathogens. Immunosuppressed patients are at risk for all types of infections; bacterial, viral, fungal, and parasitic. In the early postoperative period, the typical postsurgical bacterial infections prevail (e.g. wound infection, line infection, pneumonia). More rarely, bacterial infections present more than 1–2 months post transplant; this includes reactivation of latent tuberculosis. Viral infections are common and typically occur at or later than 6 weeks post transplant. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, often presenting as a high spiking fever and neutropenia, is the most important one. The diagnosis of CMV disease is accomplished by demonstrating viremia (CMV PCR) or tissue invasion (biopsy). In the absence of CMV prophylaxis, seronegative recipients of organs from seropositive donors have a greater than 50% risk of developing symptomatic disease. Patients with a CMV mismatch (and those who receive T-cell depleting antilymphocyte products as induction immunosuppression post transplant) must receive prophylaxis with i.v. ganciclovir followed by oral valganciclovir for at least 3 months post transplant. Other viral infections include herpes simplex virus (HSV), Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), varicella zoster virus (VZV), and adenovirus. Fungal infections are diagnosed in up to 20% of liver transplant recipients and carry significant mortality. At particular risk are patients transplanted for fulminant hepatic failure. As in other immunocompromised hosts, Pneumocystis jirovecii (formerly called Pneumocystis carinii) can cause pneumonia in liver transplant recipients and it is associated with a high mortality. Thus, prophylaxis with co-trimoxazole during the first 6–12 months post transplant is routine in most programs.

Most malignant tumors are more frequent in liver transplant recipients than in the general population. Tumor risk seems to be associated with the degree and the duration of immunosuppression. The risk for most solid tumors is moderately increased (approximately twofold). Liver transplant recipients with PSC (with or without ulcerative colitis) have an increased risk for colon cancer; many programs recommend annual screening colonoscopies in these patients and sometimes prophylactic colectomy. Patients transplanted for alcoholic cirrhosis have an increased risk of oropharyngeal, esophageal, and lung cancer. This is presumably due to a long-term smoking history that typically accompanies alcohol misuse. Solid organ transplant recipients are at high risk for EBV-associated, typically CD21 positive, B-cell lymphoma, also termed post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD). Malignant transformation of an EBV-induced polyclonal B-cell proliferation is more likely with a primary EBV infection than with reactivation of a latent infection. Thus, children who are EBV negative at time of transplant and acquire EBV infection after transplantation while on immunosuppression are at particularly high risk for PTLD.

Non-melanoma skin cancers (squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma) are also particularly common in solid organ transplant recipients. It is, therefore, recommended that solid organ transplant recipients avoid sun bathing and use sunscreen when outside. Many programs also recommend annual screening for premalignant actinic keratoses by a dermatologist. Diagnosis and therapy of all these malignancies is not different from that in the non-transplant population and should be carried out by a respective specialist. However, malignancies are generally more aggressive and carry a guarded prognosis in the immunosuppressed host.

Individual Immunosuppressive Agents (Table 11.3)

Corticosteroid.

The vast majority of programs use high-dose methylprednisolone perioperatively for the first week, followed by oral prednisone (20 mg/day) that is subsequently tapered and discontinued within 3 to 6 months. Major side effects include impaired wound healing, psychosis with the high perioperative doses, an increased incidence of infections (bacterial and fungal), insulin resistance/diabetes mellitus, weight gain, dyslipidemia, and osteoporosis.

Table 11.3 Side effects of commonly used immunosuppressive drugs

| Drug | Common side effects |

| Steroids: prednisone, methylprednisolone | Impaired wound healing, psychosis, weight gain, hypertension, insulin resistance and diabetes, dyslipidemia, acne, osteoporosis and aseptic bone necrosis, cataract |

| Calcineurin inhibitors: cyclosporine A, tacrolimus | Tremor, headaches, weight gain, hypertension, insulin resistance and diabetes, dyslipidemia, impaired renal function, hyperuricemia, hypomagnesemia, hyperkalemia, gingival hyperplasia, hirsutism, hair loss, potential for drug interactions due to extensive metabolism via CYP3A4 |

| Antimetabolites: azathioprine, mycophenolate preparations | Bone marrow suppression (in particular leukopenia), diarrhea |

| mTOR inhibitors: sirolimus, everolimus | Hypertriglyceridemia, impaired wound healing, anemia, nephrotic syndrome, lymphedema, interstitial pneumonitis |

Cyclosporine A (CsA, Available in the Microemulsified Form as Neoral).

The introduction of the calcineurin inhibitor cyclosporine A was a milestone in liver transplantation, leading to dramatically improved results. The drug has a narrow therapeutic index (efficacy vs. toxicity) and therapeutic drug monitoring is routinely performed lifelong to guide its dosage. CsA undergoes extensive hepatic metabolism though the cytochrome P450 system (CYP3A4). Drugs that induce the cytochrome P450 system, such as rifampicin, carbamazepine, and phenytoin, accelerate its metabolism and lead to decreased CsA exposure and immunosuppression. Drugs that inhibit the cytochrome P450 system, such as macrolide antibiotics (e.g. clarithromycin) and antifungals (e.g. fluconazole), inhibit its metabolism, leading to increased CsA exposure and toxicity. Possible drug interactions have to be kept in mind when starting CsA-treated transplant recipients on any new drug. Common side effects of CsA include renal dysfunction, tremor, headaches, arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia, weight gain, and insulin resistance/diabetes mellitus. Hirsutism and gingival hyperplasia are less frequent.

Tacrolimus (FK506; Prograf).

Tacrolimus is the newer of the two calcineurin inhibitors, but has a similarly narrow therapeutic index and also requires therapeutic drug monitoring. At clinically used doses, tacrolimus seems to be at least equally, and possibly slightly more, immunosuppressive compared to CsA. As for CsA, tacrolimus is extensively metabolized by the hepatic cytochrome P450 system and the same considerations regarding drug interactions apply. Both calcineurin inhibitors also share a qualitatively similar side effect profile. However, insulin resistance/diabetes mellitus seems more frequent with tacrolimus, and hirsutism as well as gingival hyperplasia more frequent with CsA.

Azathioprine (Imuran).

Azathioprine is a purine synthesis inhibitor, and inhibits the proliferation of all rapidly dividing cells such as leukocytes (including T and B cells). Its side effects include bone marrow suppression.

Mycophenolate.

The mycophenolate preparations mycophenolate mofetil (MMF/Cellcept) and mycophenolate sodium (MPA/Myfortic) block the production of guanosine nucleotides and inhibit T- and B-cell proliferation. Their main side effect is bone marrow suppression and gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea.

Other Immunosuppressive Agents

are less frequently used and include antilymphocyte preparations (ALG, ATG, thymoglobulin), which convey an increased risk for CMV re-activation, and possibly EBV associated lymphoproliferative disorder; the mTOR inhibitors sirolimus (Rapamune) and everolimus (Certican), which inhibit growth factor-dependent proliferation of hematopoetic and non-hematopoetic cells (both impair wound healing and may cause anemia, as well as lymphedema, nephrotic syndrome, and interstitial pneumonitis); and, finally, the interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor antagonist basiliximab (Simulect), which inhibits T-cell proliferation.

Long-Term Complications

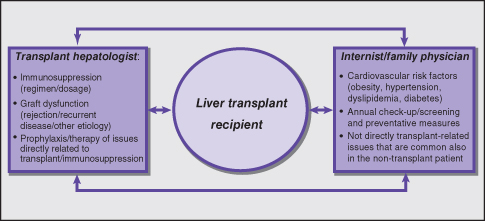

The long-term complications of liver transplantation include renal dysfunction and an increased risk for fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events. Table 11.4 and Fig. 11.1 summarize the role of the internist/family physician and of the transplant hepatologist in the shared long-term care for the liver transplant recipient in which communication between all parties involved is essential.

Table 11.4 Role of the internist/family physician and of the transplant hepatologist in the shared care of the liver transplant recipient

| Internist/family physician | Annual check-up, screening for common diseases/malignancies (including colon cancer screening) and other prophylactic measures (e.g. influenza vaccination) |

| Management of cardiovascular risk factors including overweight/obesity, high blood pressure, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance/diabetes | |

| Management of other conditions including, but not limited to, gout and osteoporosis | |

| Management of social and intellectual development in pediatric liver transplant subjects | |

| Transplant hepatologist | Management of immunosuppression (including diagnosis/treatment of rejection) |

| Management of graft dysfunction (diagnosis/therapy of underlying cause, including biliary complications and recurrent disease) | |

| Prophylaxis/therapy of immunosuppression related conditions such as infections (CMV, EBV, Pneumocystis jirovecii), certain malignancies (e.g. post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder) and renal dysfunction that require adaptation of immunosuppression as part of their management |

Fig. 11.1 Practice points/management algorithm: shared management of complications in the liver transplant recipient—communication between internist/family physician and transplant hepatologist is essential.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree