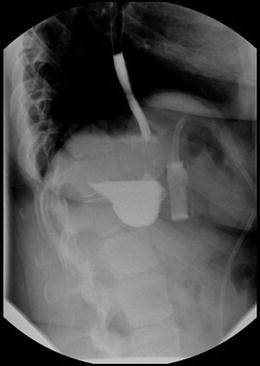

Fig. 9.1

Normal postoperative plain abdominal film with Lap-Band®. The band is visible in the upper half of the image, just to the left of the patient’s spine, while the access port is visible in the lower half, to the right of the spine

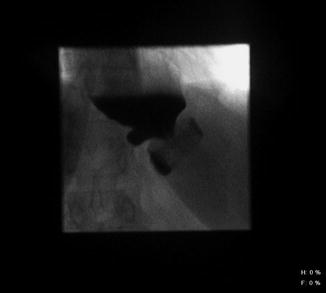

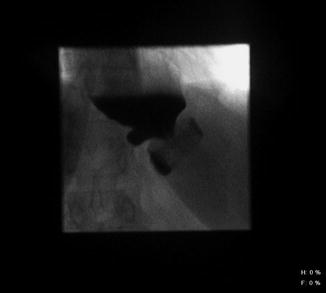

During a contrast swallow there should be roughly a 3–4 mm stream of contrast seen on fluoroscopy going through the band (Figs. 9.2 and 9.3).

Fig. 9.2

Normal immediate postoperative upper gastrointestinal swallow study after band placement

Fig. 9.3

Normal postoperative swallow study of band in patient with situs inversus associated with Kartagener’s Syndrome

9.2 Dysphagia , Gastroesophageal Dilatation and Dysmotility

Dysphagia, or difficulty swallowing, is a common symptom for band patients and may suggest a number of different pathologies. Dysphagia is differentiated from odynophagia, or pain on swallowing, and globus sensation, or a sense of a lump in the throat, particularly after swallowing. Any or all of these symptoms may be present at one time or another in band patients, and the leading cause is an overly tightened band [2]. A band may be too tight even without the radiologic findings of dilated esophagus or gastric pouch, and the diagnosis is fairly easily made in a patient who has recently had an adjustment in which fluid was added to the band. Usually a patient will report that symptoms started soon after a band fill, and the problem may be simply treated with band deflation and watchful waiting.

Patients may often report having a bolus of food become stuck at the level of the band, and that they have waited with discomfort for the bolus to pass. Often such boli do eventually pass spontaneously but sometimes have to be brought up through regurgitation, be it natural or induced. Food bolus impaction was reported as the most common cause of emergency department visits for band patients in an Australian series, representing 32.1 % of band patients seen urgently [3]. In such a presentation, the band should be deflated, which more often than not allows the bolus to pass. This can be accomplished by locating the access port by palpation and entering the center of the port with a non-coring Huber needle, then aspirating out as much saline as possible. If deflating the band is inadequate to allow passage of a stuck food bolus, endoscopy may be required to either retrieve the obstructing item or push it through the band distally. Foods that more commonly lead to obstruction or globus sensation in band patients include fibrous, poorly chewed meats and sticky “white” foods such as bread, pasta and rice. The most common symptoms of a stuck food bolus in the outpatient setting include hiccups, “productive burping” (bringing up the bolus unbidden), and “sliming.” Sliming refers to bubbling mucus that comes up the throat in response to a stuck bolus.

Other symptoms of a too-tight band include heartburn, signs of nocturnal reflux such as nighttime cough, regurgitation onto the pillow, or frank aspiration. Patients are often loathe to report that their band is too tight for fear that this will lead to deflation and that they will therefore gain weight. Sometimes a too-tight band is not brought to the surgeon’s attention until a patient presents with aspiration pneumonia.

More insidious onset of dysphagia can come about from cycles of stuck food and vomiting, after which the portion of stomach passing through the band becomes edematous. In such a situation, what might have been a good level of restriction becomes too tight, and patients often need to accommodate by regressing to a liquid diet or “slider” foods that pass through the band more easily. Advancing once more to a regular diet, particularly if the patient eats too quickly or does not chew carefully, may again cause stuck food and the need for regurgitation. Because of this, the first presentation of a too-tight band may be weight gain; patients are hungry and because they have difficulties with bulkier foods, they will turn to those items that pass more easily through the band, such as ice cream. Ongoing cycles of turning to slider foods, followed by attempts at more solid intake with concomitant vomiting, will frequently lead to dilation of the gastric pouch above the band, and eventually to esophageal dilatation. Such dilatation can be easily seen on upper gastrointestinal (UGI) swallow studies (Figs. 9.4 and 9.5).

Fig. 9.4

Upper GI swallow study in a patient with pouch and esophageal dilatation

Fig. 9.5

Upper GI swallow study in a patient with pouch and esophageal dilation. Note gastroesophageal junction can be seen below the level of the diaphragm

The anatomy seen on such studies can be confusing to both the radiologist and the surgeon. It is not uncommon to see a report of a “hiatal hernia” above the band. In order to spare patients unnecessary and potentially harmful reoperations, esophagogastric dilation should be carefully differentiated from true hiatal herniation of the pouch as seen below (Fig. 9.6).

Fig. 9.6

Herniation of gastric pouch above the diaphragm

Gastric and esophageal dilatation are common in band patients [4], particularly those who eat forcefully against the band. Cycles of overeating, stuck food and vomiting lead to fatigue of the esophageal musculature and alteration of the normal peristaltic function to the point that the esophagus can become a flaccid holding pen—in essence a second stomach in the chest above the band. When this happens, patients will frequently experience some regurgitation, but much of their ingested food will remain in the esophagus and slowly pass through the band like sand through an hourglass. Patients will be confused, therefore, by what seems to be the counterintuitive coexistence of vomiting and weight gain. Such patients must be counseled that further tightening of the band will only exacerbate the problem.

As stated previously, the treatment in such situations would include band deflation, followed by a waiting period of several weeks, followed by possible repeat imaging, and if the dilatation is improved, a slow band refill process. In cases such as this, it frequently happens that a good point of restriction is reached at a lower fill level than previously, so patients should be counseled not to perseverate about absolute quantities of fill but on satiety and restriction only.

Esophagitis and gastroesophageal reflux are not uncommon after gastric banding [4], and may present as abdominal or chest pain, dysphagia, or night cough. There are conflicting reports of the band either improving or worsening heartburn in patients, but in the majority of band patients simple heartburn is amenable to treatment with medications. Severe, unrelenting heartburn should be investigated, as it may be a sign of a more serious diagnosis. Cases of erosive esophagitis with hemorrhage have been seen with a band that is too tight, even in the absence of other pathology such as prolapse .

Esophageal dysmotility after banding is another entity that may be noted on UGI studies (Figs. 9.7 and 9.8).

Fig. 9.7

Pouch and esophageal dilation, with pouch herniated above the diaphragm, and with tertiary waves of esophageal contraction

Fig. 9.8

Pouch and esophageal dilation, with associated tortuosity of esophagus from forceful eating against the band

If contrast or motility studies were not performed preoperatively, and in most practices they are not, it will not be possible to definitively determine if the patient had baseline altered motility prior to band placement or if such dysmotility developed secondary to the presence of the band. Dysmotility may be seen to improve on imaging studies after band deflation, but it is important to be aware that it may return with ongoing fills. In some patients, dysmotility makes it impossible to achieve a good point of restriction without causing dysphagia.

Patients should be made aware that after band deflation, food will generally pass more easily. Because of this, patients who have been suffering with a too-tight band may, after deflation, celebrate their renewed ability to eat, and therefore may rapidly gain or regain weight. This can be avoided by protein shake meal replacements, mindful eating with reasonable portion sizes and good food choices, and separating liquid from solid foods during meals, i.e., revisiting their preoperative dietary counseling. A good analogy for band patients is that they must not think of their band as an “air bag.” When driving, one should not wait for the air bag to deploy in order to know to slow down; just as one should drive at a proper speed and stay within the lane markings rather than waiting for external cues, patients must learn to preselect their portion sizes, chew carefully, and eat slowly. By this analogy, stuck food or vomiting should not be the cue that tells band patients to slow down and eat mindfully.

On the topic of band deflation, bariatric programs need practitioners who are adept at band adjustments. Such adjustments may be done in a variety of ways, according to surgeon or practitioner preference. This may include such techniques as following a prescribed volume algorithm for a given band while accessing the band, with or without local anesthetic, on an examination table; filling the band under fluoroscopic imaging with the patient in a sitting or standing position while swallowing contrast material; or filling the band with the patient in the sitting position while drinking water and tightening the band to the point where the water passes slowly. However the adjustment is done, it should always be done with a Huber non-coring needle to minimize the risk of injury to the silicone diaphragm; this can happen with other needles that may remove a core of the diaphragm during needle passage, thus allowing the fluid to slowly leak out of the access port and thus rendering the system nonfunctional.

9.3 Gastric Prolapse

Prolapse of a portion of the stomach up through the band may also be referred to as a “slippage ” or “slipped band.” It is helpful to remember that the band is not actually slipping down onto the distal stomach, but that the stomach itself is prolapsing upward through the band, usually secondary to forceful vomiting. This is the most common intra-abdominal complication of banding [2] and one that may require an abdominal operation for resolution. Prolapse was a more common complication in the early days of banding, when a perigastric approach was used [5]. The now-preferred pars flaccida approach, in which the gastrohepatic ligament is entered, the medial aspect of it is held within the band–stomach complex, and entry into the lesser sac is avoided, has significantly decreased the risk of prolapse. While the majority of surgeons perform a gastrogastric plication over the anterior portion of the band in order to prevent prolapse, there are surgeons who avoid this step, claiming it takes additional time and does not prevent prolapse. These results remain controversial [6]. In an acute presentation of prolapse, a patient generally has had an episode of acute vomiting or retching, followed by complete or near-complete obstruction to passage of food or even liquids at the level of the band. As with a band that is simply too tight, there may be associated heartburn, or signs of nocturnal reflux. With such symptoms, the band should be completely deflated. If deflation leads to complete resolution of symptoms, it is possible that the patient simply had a too-tight band. However, it is also possible for a prolapse to completely reduce upon band deflation.

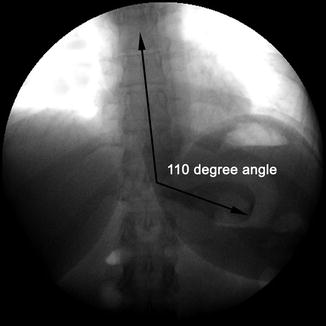

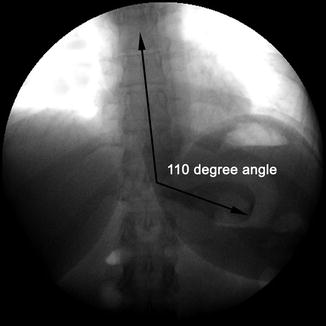

On plain films or fluoroscopy, a band prolapse will be demonstrated by a change in the angle of the band such that it no longer points toward the left shoulder. This comes about from pressure of the prolapsed stomach pushing down on the band (Fig. 9.9).

Fig. 9.9

Expansion of the usual 45° angle of band, which no longer points toward the left shoulder. This patient was found to have a gastric prolapse

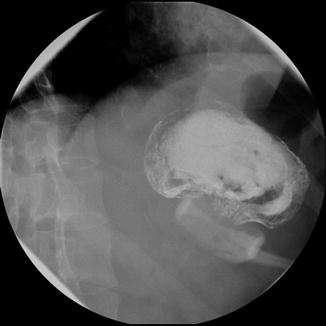

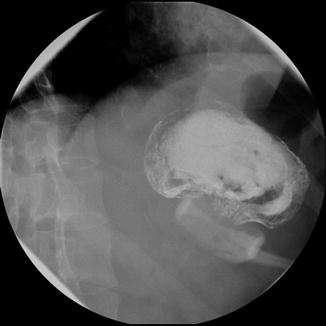

In extreme cases, a prolapse will present as an “O” sign in which the lumen of the band is clearly visible on an A-P projection (Fig. 9.10).

Fig. 9.10

Complete posterior prolapse causing extreme angulation of the band

An UGI swallow study with contrast is the best way to image many band complications, including prolapse. This may show pouch dilatation or eccentric pouch dilatation with or without esophageal dilatation, delayed passage of contrast material, flattening or reverse angulation of the band itself, and excessive pouch overhanging the band (Figs. 9.11 and 9.12).

Fig. 9.12

Upper GI contrast study of patient with large anterior prolapse

Acute gastric prolapse generally requires hospital admission and resuscitation, and may require operative intervention. Indications for operation include ongoing obstruction and abdominal pain even after complete deflation of the band. Pain implies the possibility of gastric ischemia, which may progress to frank necrosis. This can lead to the need for resection and if untreated can potentially lead to perforation and death [7].

Operative treatment of symptomatic, unreduced gastric prolapse can generally be accomplished laparoscopically. Gentle downward traction on the stomach may reduce it through the band, although the presence of adhesions and gastric edema may prevent this. Sometimes takedown of the area of gastrogastric suturing, if present, may facilitate gastric reduction. If this is unsuccessful, an attempt may be made to unbuckle the band; however, this can be exceedingly difficult with certain band types. If unbuckling is successful, there are various options including simply leaving the band unbuckled with the decision made to come back at a later date to replace and rebuckle the band. Another option is to replace the band in an appropriate position above the prolapsed portion of stomach and again perform gastric plication with interrupted sutures toward the greater curvature. In cases where the prolapse cannot be reduced and the band cannot be unbuckled, it may be sharply transected and removed or replaced. Band replacement may be done through an entirely new retrogastric instrument passage, or by suturing a new band to the transected old band and pulling it through the retrogastric tract, then assuring good position by placing the new band cephalad to the formerly prolapsed segment. It is important to assure that the newly buckled band is not too tight around the stomach, by assuring that a smooth grasper passes easily between the band and the stomach. This can also be confirmed with intraoperative gastroscopy. Note that if there is any sign of gastric necrosis or perforation, the band system should be entirely removed and the ischemic area addressed in an appropriate fashion.

Gastric prolapse may also come to the surgeon’s attention insidiously, after many months of mild symptoms suggestive of a too-tight band. Prolapse not associated with vomiting or abdominal pain may be treated in a more elective fashion, but in many cases will ultimately come to the need for surgical treatment.

9.4 Erosion

Band erosion into the stomach has an estimated incidence of 1–6 % [8–10]. While the stomach is the most common site, erosion into nearby organs has also been reported, including the liver, transverse colon, duodenum, jejunum, celiac axis, renal hilum, and spleen [8, 11]. Erosions have been classified as occurring early (<6 months) or late (>6 months) [12]. Early erosions are rare and are likely a result of unrecognized gastric or esophageal injury at the time of band placement. Whether early or late, band erosion is generally an indolent process, although there have been case reports of more urgent presentation, such as with massive upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage and circulatory collapse, or with complete circumferential necrosis of the gastric wall separating the pouch from the distal stomach, requiring total gastrectomy and splenectomy for sepsis [13, 35].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree