Chapter 87 VULVAR AND VAGINAL PAIN, DYSPAREUNIA, AND ABNORMAL VAGINAL DISCHARGE

DEFINITION OF VULVODYNIA AND CURRENT NOMENCLATURE

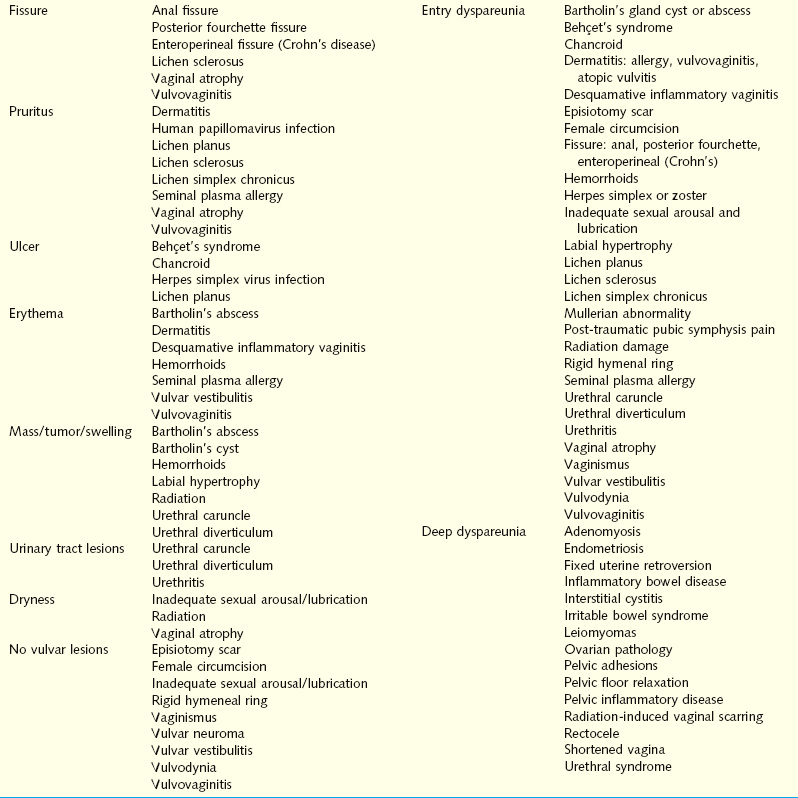

The purpose of this chapter is to outline the anatomy and physiology of vulvar and vaginal pain syndromes and to explore the differential diagnosis and management of vulvar and vaginal pain and dyspareunia (Table 87-1 and 87-2), including the roles of medication, surgery, psychotherapy, and multidisciplinary pain management. The differential diagnosis and management of abnormal vaginal discharge is also discussed.

Table 87-2 Evaluation of Patients with Vulvar or Vaginal Pain

| History | Detailed pain history, obstetric/gynecologic, sexual, medical, surgical, psychosocial, medications, allergies, habits, trauma |

| Vulvar examination | Inspection: lesions (macules, papules, ulcers, nodules), fissures, fistulas, inflammation (edema, erythema), discharge, tumors, anatomic abnormalities (surgical, congenital, traumatic). |

| Palpation: localize pain with cotton swab, identify specific neural distribution, vestibule, Bartholin’s, Skene’s, hymenal caliber, urethra | |

| Biopsy and/or culture suspicious lesions (e.g., VIN, ulcers, verrucae, white or red plaques); colposcopic magnification of lesions if indicated | |

| Vaginal examination | Speculum examination: inspect mucosa (color, rugations, lesions) |

| pH of discharge | |

| Wet mount saline and KOH: infection, atrophy | |

| Culture (fungal, bacterial): vagina, cervix | |

| Cystocele, rectocele, enterocele, uterine prolapse, cervical discharge, lesions | |

| Palpate, attempt to reproduce pain: hymen, bladder, individual pelvic floor muscles, ischial spine area for pudendal nerves, inferior hypogastric plexus (paracervical), cervical motion tenderness | |

| Assess ability to contract and relax muscles | |

| Bimanual examination | Uterus: size, shape, position, mobility, tenderness, uterosacral ligament thickening/nodularity, tenderness, adnexal masses, tenderness, mobility |

| Cervical motion tenderness | |

| Rectovaginal examination | Rectal masses, stool guaiac, nodules/fibrosis in cul-de-sac |

| Additional diagnotic tests as needed | Pelvic floor MRI, pelvic ultrasound, pudendal nerve conduction velocity, diagnostic nerve blocks (local, pudendal, inferior hypogastric), cystourethroscopy, sigmoidoscopy, physical therapist evaluation of pelvic floor, psychological/stress/couples evaluation, HSV serology, urine analysis and culture |

| Create differential or specific diagnoses | Specific infectious, inflammatory, or anatomic pathology. |

| Treat per diagnosis (e.g., pharmacologic, surgical) | |

| Neuroplastic or neuropathic/neuromuscular pain requires a multidisciplinary approach: physical therapy, psychology (cognitive/behavioral/biofeedback/sexual), series of specific nerve blocks, pharmacologic (medications to alter nerve conduction or for depression/anxiety, such as antidepressants, anticonvulsants, local anesthetics, or muscle relaxants [Botox]) |

HSV, herpes simplex virus; KOH, potassium hydroxide; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; VIN, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasm.

Vulvar pain syndromes are characterized by unexplained burning or any combination of stinging, irritation, itching, pain or rawness anywhere from the mons pubis to the anus that causes physical, sexual, and psychological distress. A multitude of terms have been used in the literature to describe vulvar pain syndromes. Vulvodynia was first described in 1889 by A. J. C. Skene1 but received little attention until the 1970s. The International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Diseases (ISSVD) abandoned the term “burning vulva syndrome,” first described in 1984,2 and introduced a classification wherein the two principal divisions were vulvar vestibulitis syndrome (VVS) and dysesthetic or essential vulvodynia.3 The most recent classification of vulvar pain, which was agreed on at the October 2003 Congress of the ISSVD, consists of two major categories4:

INCIDENCE AND EPIDEMIOLOGY OF VULVODYNIA

The typical patient with vulvodynia used to be described as a nulliparous woman in her 20s or early 30s who often may have developed symptoms suddenly.5 The true prevalence of vulvodynia is uncertain due to its recent recognition; however, a 1991 study of 210 consecutive patients seen at a private practice for general gynecology found that 37% had some degree of positive testing for vulvar discomfort, and 15% met full criteria.6 A survey of more than 4900 women aged 18 to 64 years reported that 16% of the 3000 respondents had experienced vulvar pain lasting at least 3 months; 7% had vulvar pain at the time of the survey, and many had seen up to five different doctors for this problem.7 Unexplained vulvar pain was found to be of similar incidence among white and African American women. Hispanic women were 80% more likely than white women to have experienced chronic vulvar pain.

ANATOMY OF THE VULVA AND VAGINA

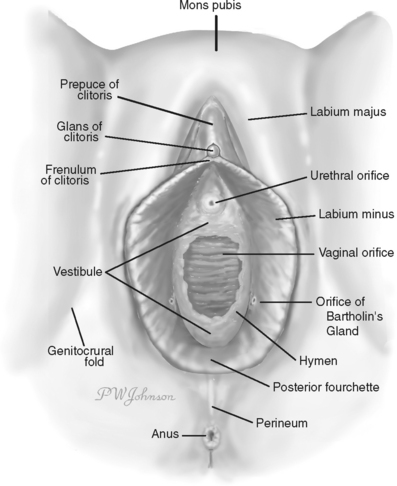

The vulva is the part of female anatomy located between the genitocrural folds laterally and between the mons pubis anteriorly and the anus posteriorly (Fig. 87-1).8 It is composed of the labia majora, labia minora, mons pubis, clitoris, vestibule, urinary meatus, vaginal orifice, hymen, Bartholin’s glands, Skene’s ducts, and vestibulovaginal bulbs.

Figure 87-1 Vulvar anatomy.

(Redrawn from Kaufman RH: Benign Diseases of the Vulva and Vagina, 5th ed. St. Louis, Elsevier Mosby, 2005.)

The labia minora lie between the labia majora and consist of two flat folds of connective tissue containing little or no adipose tissue. They are covered by skin on their lateral aspects and partially so on their medial aspects. Hart’s line separates the medial boundary of the minora from the vestibule and is the line of demarcation between the skin and mucous membrane; it runs along the base of the inner aspect of each labia minora, passes into the fossa navicularis, and separates the skin boundary of the fourchette from the mucous membrane of the hymen. The labia minora are 4 to 5 cm in length and 0.5 cm in thickness. Anteriorly, each divides into two parts, one passing over the clitoris to form the prepuce and the other joining the clitoris to form the frenulum. Posteriorly, they tend to become smaller and blend with the medial surfaces of the labia majora or unite anterior to the posterior commissure to form the fourchette. The skin and mucosa of the labia minora are extremely rich in sebaceous glands. During sexual excitement, the labia minora frequently become swollen and congested and take on the appearance of erectile tissue.

The vestibule is the portion of the vulva that extends from the clitoris to the fourchette and is visible on separation of the labia majora. Hart’s line represents the outer perimeter of the vulvar vestibule, and the inner margin of the vestibule is the hymen. The vestibule is covered by nonpigmented, nonkeratinized squamous epithelium and is devoid of skin adnexa. It contains mucus-secreting minor vestibular glands. The ductal orifices of Bartholin’s glands, the periurethral gland complexes of Skene, and the urethral meatus all empty onto the vestibular surface. The vagina opens into the vestibule. The hymen is the thin membrane of connective tissue over the entrance of the vagina into the vestibule. Bartholin’s glands lie deep beneath the fascia, one on each side of the vestibule, posterolaterally to the vaginal orifice. The cells lining the acini contain mucin, which is secreted during sexual excitement and contributes to lubrication of the vaginal orifice. The main ducts of Bartholin’s glands open into the vestibule at approximately the 5 and 7 o’clock positions, outside the hymenal ring. The urethra opens into the vestibule just anterior to the vaginal introitus.

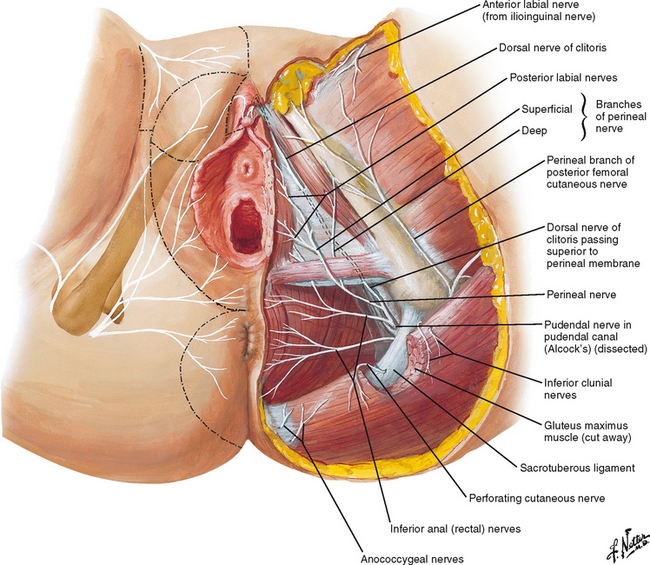

Innervation of the vulva is supplied by the cutaneous branches of the ilioinguinal nerve anterosuperiorly and by the pudendal branches of the femoral cutaneous nerve posteroinferiorly (Fig. 87-2). The three roots of the pudendal nerve derive from the second, third, and fourth sacral nerves; they unite approximately 1 cm proximal to the ischial spine, then leave the pelvic cavity by passing though the greater sciatic foramen.9 The pudendal nerve subsequently passes posterior to the junction between the ischial spine and the sacrospinous ligament, then reenters the pelvic cavity through the lesser sciatic foramen and proceeds anteriorly through Alcock’s canal. The major cutaneous nerve supply of the perineum is provided by the branches of the pudendal nerve.9 The inferior hemorrhoidal nerve supplies the posterior portion; the superficial branch of the perineal nerve divides into medial and lateral parts known as the posterior labial nerves, and the dorsal nerve of the clitoris innervates the clitoral area.

Figure 87-2 Nerves of perineum and external female genitalia.

(Redrawn from © Netter images “Nerves of Perineum and External Genitalia Female.” www.netter images.com).

The pelvic floor muscles include the levator ani, pubococcygeus, and coccygeus muscles. All of the fasciae investing the muscles form a continuum of connective tissue that joins the fascial covering of the pelvic viscera above with the fascia of the perineum below.9 The levator ani muscle is a broad, thin structure that is attached to the inner surface of the side of the true pelvis.9 It is attached anteriorly to the pelvic surface of the body of the pubis, lateral to the symphysis; behind, to the medial surface of the spine of the ischium; and between these two points, to the obturator fascia. Morphologically, the levator ani can be divided into the pubococcygeus and the iliococcygeus muscles.

EVALUATION

History

Obtaining a thorough history is critical in the evaluation and management of vulvar or vaginal pain and dyspareunia (see Table 87-2). Pain symptoms must be well characterized to assess the onset, type of pain (burning, itching, stinging, irritating), timing (constant or cyclic), associated activities (e.g., intercourse, exercise, stress), inciting agents (perfume, lotions, detergents, clothing), and relieving factors (e.g., antifungal medications). A daily pain diary may better define these characteristics. Pain should be quantified on each visit on a scale of 1 (no pain) to 10 (maximal pain imaginable). Concurrent gynecologic, genitourinary, and gastrointestinal symptoms should be identified.

In addition, past or current infections (human papillomavirus [HPV], herpes, Candida), medications, local and systemic dermatologic disorders, neurologic disorders (e.g., herniated disk, herpes zoster, pudendal or genitofemoral neuralgia), urologic disorders (interstitial cystitis, urethral syndrome), physical trauma (vaginal deliveries, episiotomy, vaginal surgery), and fibromyalgia should be ascertained. Sexual history evaluating arousal, lubrication, ability to achieve orgasm, whether pain is primary or secondary, and a history of sexual, physical, or emotional abuse should be addressed.10

Physical Examination

In many cases, the vulva appears normal. However, careful inspection should be performed to evaluate for discoloration (erythema, hypopigmentation, or hyperpigmentation), lesions (ulcers and fissures) and atrophy (white epithelium consistent with lichen sclerosis or absence of well-estrogenized tissue). On examination, tenderness (hyperesthesia) at the periurethral or Bartholin’s glands and the vulvar vestibule should be outlined using a cotton-tipped swab, scored (on a scale from 0, no pain, to 10, severe pain), and recorded.

Vaginal pH, whiff test, and microscopic examination of the vaginal secretions with saline and potassium hydroxide (KOH) should be performed to rule out vaginitis, vaginosis, and vaginal atrophy. Vaginal fluid may be cultured for Candida (because microscopic evaluation reveals candidiasis in only 50% of cases), bacterial culture and immunoglobulin E (to evaluate for local allergy). All lesions or discolorations should be further evaluated by colposcopy or biopsy to evaluate for an underlying dermatosis or an infectious or neoplastic process.10

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF VULVAR OR VAGINAL PAIN

Vaginitis

The vaginal mucosa has only a few nerve endings needed for the sensations of pain and light touch.11 For this reason, many vaginal infections are asymptomatic until the discharge reaches the vulva, where there is abundant somatic innervation. The problem is then perceived as vulvar itching, burning, or pain.

Vaginal Ecology

In childhood and menopause, in the absence of estrogen, the vaginal epithelium is thin and undifferentiated.11 Estrogen causes thickening of the epithelium and a differentiation into wellrecognized layers (basal, intermediate, and superficial). The percentage of superficial cells on a vaginal smear is indicative of the amount of estrogen activity. The vagina has a large amount of glycogen, second only to the liver, and it is most available in the superficial layers. Estrogen effects the formation and deposition of glycogen in the vagina.

Vaginitis: Description, Diagnosis, Treatment

Bacterial Vaginosis

Bacterial vaginosis, the leading cause of abnormal vaginal discharge (according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 1996) is a polymicrobial syndrome in which synergistic activity occurs among a characteristic set of bacterial species (Gardnerella vaginalis and anaerobic bacteria).12 Risk factors for bacterial vaginosis infection include multiple or new sexual partners (male or female), early age at first coitus, douching, cigarette smoking, and use of an intrauterine contraceptive device. Approximately 50% to 75% of women who have bacterial vaginosis are asymptomatic. Symptomatic bacterial vaginosis is associated with a “fishy” odor, thin white or gray discharge, absence of pruritus, and inflammation with rare dysuria and dyspareunia.

Diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis is by clinical criteria. Three of the four Amstel criteria have been traditionally needed for diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. However, a recent study showed that use of only two of the four criteria does not change the specificity or sensitivity of diagnosis.13 The Amstel criteria include the following:

Treatment of bacterial vaginosis is indicated for patients with symptomatic infection, those with asymptomatic infection before abortion or hysterectomy, and asymptomatic women with previous preterm births. It is not necessary to treat sexual partners. The condition spontaneously resolves in up to one third of women. Treatment regimens include metronidazole or clindamycin, orally or intravaginally. Metronidazole is the most successful therapy, with cure rates of greater than 90% in 1 week and 80% at 4 weeks.14,15 The recommended dose is 500 mg twice a day for 7 days.16 Topical vaginal therapy with 0.75% metronidazole gel, 5 g once daily for 5 days, is just as effective as the oral regimen.16,17 A single oral dose of 2 g of metronidazole is an alternative regimen with higher relapse rate but a similar immediate rate of response.16 Clindamycin appears to be less effective but is a reasonable alternative to metronidazole. It is available as topical vaginal therapy 2% cream, 5 g once daily for 7 days, or oral therapy at 300 mg twice daily for 7 days, or ovules 100 mg once daily for 3 days. Other, less effective therapies include triple-sulfa creams, erythromycin, tetracycline, acetic gel, povidone-iodine pouches, ampicillin, and amoxicillin.

Candida

Candida vulvovaginitis accounts for approximately one third of vaginitis cases. Studies suggest that 75% of women will suffer an attack at least once in their life.8 The infection is less common in postmenopausal women unless they take estrogen therapy. About half of those infected experience more than one episode.

Candida albicans infection accounts for 80% to 90% of candidiasis cases; the remainder are evenly split between Candida glabrata and Candida tropicalis. The presence of estrogen, directly or indirectly, enhances candidal growth.18 The organism thrives in many body locations, such as vaginal fluid,19 as well as unsterile saliva.20 In one study, one half of infected patients were found to harbor Candida in the mouth, and about one third had Candida in the anorectal tract; one fourth were found to be colonized in the vagina.21 Besides the gut and vagina, intertriginous skin areas are especially susceptible including the vulva, groin, axillae, coronal sulcus, and the skin folds of the breast and panniculus. The organism needs warmth and moisture and does not survive long on dry skin. Tight-fitting clothing, especially if made of synthetic fabric, is more conducive to Candida than loose clothing is.

The mechanism by which Candida species cause symptomatic disease is complex, and includes the host inflammatory response to invasion and yeast virulence factors (e.g., elaboration of proteases). Factors predisposing to symptomatic infection include diabetes, immune suppression, pregnancy, oral contraceptives, antibiotics, metabolic factors (hypothyroidism, anemia, zinc deficiency), and diet. Pregnancy is the most common predisposing factor, with the incidence and severity of infection increasing with the duration of gestation. The increased glycogen content and high hormone levels constitute a favorable environment for the growth of candidal organisms. The newer oral contraceptives have lower estrogen levels and do not seem to predispose patients to Candida infection. Furthermore, one study found that only pill-using women with active herpetic, condylomatous, or anaerobic vaginal infections had increased prevalence of candidiasis.22 Antimicrobials are thought to act as predisposing factors by reducing the number of protective resident bacteria. Some studies have shown that those patients who go on binges of dietary sweets suffer from recurrence of candidiasis and have high levels of urinary sugars derived from lactose and sucrose. By restricting lactose intake, 90% of these patients were able to maintain disease free intervals for longer than 1 year. If a patient has chronic refractory candidiasis, one may consider the possibility of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Candidiasis has not been traditionally considered a sexually transmitted disease (STD), especially because it does occur in celibate women. However, it may be linked to orogenital sex.23

Treatment of candidiasis is indicated for relief of symptoms. Those who harbor Candida but are asymptomatic do not require therapy. Most patients (90%) have uncomplicated infections. The most commonly used antifungal agents are the azoles. There are both oral and vaginal preparations. The only oral preparation recommended is fluconazole: a 150-mg dose of fluconazole is as effective as multiple doses of intravaginal clotrimazole and oral butoconazole. Complicated infections occur in women with uncontrolled diabetes, immunosuppression, or a history of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis, and in those who are infected with Torulopsis (Candida) glabrata, or C. tropicalis. These women are less likely to respond to short courses of antimycotic drugs and may require 7 to 14 days of topical therapy or two doses of oral therapy 72 hours apart. Between 65% and 70% of those infected with C. glabrata respond to intravaginal boric acid (600 mg daily for 2 weeks), or a cure rate of more than 90% may be achieved with flucytosine cream (5 g nightly for 2 weeks).24 Documented recurrent infections warrant testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and glucose tolerance testing and may require weekly and then monthly therapy for 4 to 6 months.

Trichomonas

The prevalence of Trichomonas infection depends greatly on the population studied. Trichomonas was found in 3% of unselected, asymptomatic college women,25 15% of private patients with leukhorrea,26 6% to 8.9% of pregnant women,27 and 34% of pregnant inner-city adolescents.28 Nevertheless, there seems little justification for screening low-risk, nonpregnant, asymptomatic individuals.

Trichomonas vaginalis is a unicellular protozoan flagellate, round or almond-shaped, slightly larger than a polymorphonuclear leukocyte.8 Under high-power microscopy, four flagella can be seen to protrude from the forward end of the trichomonad. They are found in the vagina, urethra, and paraurethral glands.

This disorder is almost always sexually transmitted and can be identified in 30% to 40% of male sexual partners of infected women. The infection is associated with a high prevalence of coinfection with other STDs. There is a positive association between trichomonas infection and HIV infection.29 Trichomonads can survive in an aqueous environment between 20 and 30 degrees and can remain infectious for up to 24 hours.30 Women can deposit the trichomonads on toilet seats, on which the organism can survive up to 45 minutes.31

The most practical and cost-effective diagnostic test available is still the saline wet mount done in a clinic setting.8 However, motile trichomonads are found only in 50% to 70% of culture-confirmed cases. Culture on Diamond’s medium is 95% sensitive and more than 95% specific but should only be used if there is a high clinical suspicion despite a negative wet mount result, or wet mount is unavailable. Diagnosis with classic Pap smears is not recommended, but diagnosis with liquid-based pap smears has been shown to be highly specific (99%) and sensitive (61%).32

Treatment is indicated in all nonpregnant women diagnosed with Trichomonas vaginitis and their sexual partners. Trichomonas is associated with preterm rupture of membranes and prematurity in pregnant women, but treatment has not been shown to decrease these complications.33 Oral metronidazole is the treatment of choice; it is preferred over the vaginal route, because systemic administration achieves therapeutic drug levels in the urethra and periurethral glands, which serve as sources for endogenous recurrence. There is no need to identify the source in the male partner before treating him. It has been shown that a single 2-g dose to both sexual partners is as effective as the classic regimen, 500 mg twice a day for 7 days.34 The advantages of the single-dose regimen include better compliance, a lower total dose, shorter period of alcohol avoidance (due to the disulfiram-like effect of metronidazole), and possibly decreased Candida superinfection. In the event of treatment failure, the 7-day regimen should be prescribed before resistance is suspected; many cases of “failure” result from reinfection, possibly from a different or untreated partner.8

Desquamative Vaginitis

Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis (DIV) is not a diagnosis in itself and may be the presentation of a range of blistering disorders, including pemphigus vulgaris, lichen planus, and mucous membrane pemphigoid.35 The existence of an idiopathic subset of DIV remains controversial. It is a rare but disabling condition and manifests in women of any age with a history of discomfort, irritation, and dyspareunia. Women who develop DIV are different from those who typically develop STDs, being older, married, and with higher levels of education. Patients may complain of increased yellow vaginal discharge.

Examination of the vulva is normal, but erythematous regions on the vaginal walls are evident, with increased vaginal secretion. Repeated cultures are negative for pathogenic bacteria, viruses, and yeast. Microscopic examination of the vaginal discharge shows an increased number of immature epithelial cells, typical rounded parabasal cells, and an increase in polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Gram staining shows an absence of lactobacilli and occasionally increased levels of gram-positive cocci. The vaginal pH is increased from normal to 7.4. A biopsy of the erythematous portion of the vaginal wall for histology and immunofluorescence is necessary to exclude any underlying cause of DIV.

This sterile inflammatory vaginitis is difficult to treat, but successful therapy has been reported with steroids and clindamycin. Studies have found that 2% clindamycin suppositories or high-potency intravaginal steroids alone or in combination with oral clindamycin for 4-6 weeks have been effective.36,37 Estrogen deficient women need supplementary vaginal estrogen therapy to maintain remission.

Herpes Simplex Virus

In the United States, the frequency of genital herpes simplex virus (HSV) is increasing. There are two types of HSV infection; it is reported that HSV-2 causes the most genital infections, and HSV-1 causes the most labial infections. However, HSV-1 genital infections are very common. Prevalence of HSV is high: 21.9% were positive among 13,094 individuals surveyed by the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination.8 HSV is more commonly associated with women, African Americans, single marital status, higher number of sex partners, prior history of an STD, and urban residence.8

Infection is transmitted by direct sexual contact, most commonly when an active virus-secreting lesion is present. HSV has been recovered from asymptomatic male carriers and from the cervix of asymptomatic women. Subclinical shedding is common, occurring in 55% of women with HSV-2 and 29% of women with HSV-1.38 In 70% of patients, transmission was linked to sexual contact during periods of asymptomatic viral shedding. Transmission of genital HSV was documented in 14 couples, and the risk was greater with male than female source partners (17% versus 4%).12

The types of genital HSV infection are primary, nonprimary first episode, and recurrent. The clinical manifestations of genital HSV are variable, depending on the type of infection.39,40 In acute primary and recurrent infections, the initial presentation can be severe, with painful ulcers, dysuria, fever, tender inguinal lymphadenopathy, and headache. Other patients have a mild presentation or are entirely asymptomatic.39,41 Recurrent infections are typically less severe than primary or nonprimary first-episode infections because of preexisting immunity. In turn, a non-primary first episode is typically less severe than the primary infection, because the antibodies to one HSV type offer some protection against the other. Recurrent infections are more common with HSV-2 than HSV-1: 60% versus 14% in patients with a first symptomatic episode of genital herpes.42 Recurrent lesions are fewer in number and are more often unilateral than bilateral.39

In a primary infection, the average incubation period is 4 days.40 Patients usually have multiple, bilateral, ulcerating, pustular lesions that resolve after a mean of 9 days. Other symptoms include systemic headache, malaise, fever, and myalgia (67%); local pain and itching (98%); dysuria (63%); and tender lymphadenopathy (80%). Virus is very often isolated in the urethra and cervix of women with first-episode infection.39 Extragenital manifestations of HSV include orolabial symptoms, aseptic meningitis, urinary bladder retention, distant skin lesions, herpetic whitlow, and proctitis. The clinical manifestations of HSV in immunocompromised patients are more extensive and include mucocutaneous involvement, variable appearance of genital lesions, and the development of chronic and recurrent ulcers. Patients may have prolonged viral shedding. In addition to genital symptoms, patients may also have more neurologic complications, such as aseptic meningitis, sacral radiculopathy, and transverse myelitis.43

The differential diagnoses of HSV include syphilis, chancroid, Behçet’s disease, and drug eruptions. Diagnosis based on history and physical examination is often inaccurate, and laboratory testing is required. Diagnostic tests include viral culture, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and direct fluorescence antibody (DFA). Viral cultures can be obtained with active lesions; the vesicle should be unroofed for sampling of the vesicular fluid. The overall sensitivity of viral culture is 50%,44,45 and the highest yield is in the early vesicular stages rather than the later, crusted stages.46 HSV PCR is a more sensitive method for samples taken from genital ulcers, mucocutaneous sites, and cerebrospinal fluid, and it is particularly useful in detecting asymptomatic viral shedding.47–49 DFA is specific, reproducible, and less expensive than PCR. Serology is important because it is type-specific and antibodies persist indefinitely in the serum.

Because HSV is a viral disease, there is no cure; however, drug treatment can shorten the duration of symptoms, and, in patients with frequent recurrences, medicine can be used as prophylactic therapy. There are three main drugs used in the treatment of HSV: acyclovir, famciclovir, and valacyclovir. In 2002, the Centers for Disease Control published treatment guidelines for the various types of HSV infection.16 Recommended regimens for individuals with first episode are acyclovir (400 mg PO three times daily or 200 mg PO five times a day), famciclovir (250 mg PO three times daily), or valacyclovir (1 g PO twice daily) for 7 to 10 days. Recommended regimens for individuals for suppressive therapy are acyclovir (400 mg PO twice daily), famciclovir (250 mg PO twice daily), or valacyclovir (1 g PO daily or 500 mg PO daily). Recommended regimens for individuals with recurrent episodes are acyclovir (400 mg PO three times daily or 200 mg PO five times a day or 800 mg PO twice daily), famci-clovir (125 mg PO twice daily), or valacyclovir (1 g PO daily) for 5 days or valacyclovir (500 mg PO twice daily) for 3 to 5 days. Postherpetic neuralgia due to HSV has not been well documented, although the herpes virus can increase the risk of vulvodynia due to recurrent herpes prodromal symptoms or pudendal neuropathy. Prodromal symptoms may be accom-panied by positive HSV immunoglobulin M antibody serology; they respond to antiviral agents, whereas the pudendal neuro-pathy does not.

Human Papillomavirus

HPV infection can lead to vulvar itching and pain through its anogenital manifestations. Condylomata acuminata usually manifest as single or multiple papules on the vulva, cervix, vagina, perineum, or anal region. The most common sites in women are the posterior introitus, followed by the labia majora and labia minora. External HPV lesions are frequently associated with cervical lesions. The lesions are flesh-colored, hyperkeratotic, exophytic, and either sessile or pedunculated.50 HPV subtypes, other than the low-risk types 6 and 11, are also closely associated with squamous intraepithelial lesions of the cervix.

There are several treatments for anogenital warts. For home therapy, podophyllotoxin or imiquimod may be used. For office therapy, podophyllin or 40% trichloroacetic acid may be used. Surgical options include cryotherapy, laser therapy, electrosurgery, and surgical excision.