Anatomic Considerations

■ Characteristics of the posterior hepatic IVC. The posterior hepatic IVC extends from the renal veins to the confluence of the right atrium (RA). This is further divided anatomically into the inner segment of the pericardium (intrapericardial IVC), the suprahepatic IVC below the diaphragm, the retrohepatic IVC, and the lower segment of the subhepatic renal vein. The IVC is thick-walled, tenacious, elastic, and not particularly susceptible to invasion. The hepatic veins are thin-walled but rapidly develop thicker walls as they insert into the IVC. Thus, the proximal portions of the hepatic veins are at greatest risk for injury during the operation. Such injury invariably results in intraoperative hemorrhage and/or air embolism.

■ Characteristics of tumors that involve the IVC. Most liver cancers near the IVC originate from hepatic segments 1, 4, 5, and/or 8, or in the paracaval portion of the caudate (referred to by some as segment 9).

■ Caudate tumors: Anatomically, the hepatic caudate lobe is divided into the left hepatic caudate lobe (Spigelian lobe, caudate lobe proper, segment 1) and right hepatic caudate lobe (dorsal sector). The right hepatic caudate lobe can be further divided into the paracaval portion (segment 9) and the caudate process (segment 10).23–26 Caudal tumors may either extend anteriorly and thus invade the portal vein and/or the bile duct, resulting in obstructive jaundice, or extend posteriorly and thus invade the IVC. Generally, about one-fourth of caudate tumors involve the IVC.27,28

■ Tumors arising near the root of the hepatic veins: These tumors typically compress the anterior IVC between the mid and right hepatic veins or between the mid and left hepatic veins. Because the hepatic veins have no valves, are thin-walled, and fixed in the hepatic parenchyma, they are unable to retract upon injury and air embolism is liable to occur. To avoid air embolism and massive hemorrhage, the operative strategy should plan to isolate the hepatic veins extrahepatically and occlude them in advance.17–19 The risk in resecting tumors that are near the confluence of the hepatic veins with the IVC is not rupturing the IVC but injuring the thin wall of the hepatic veins.

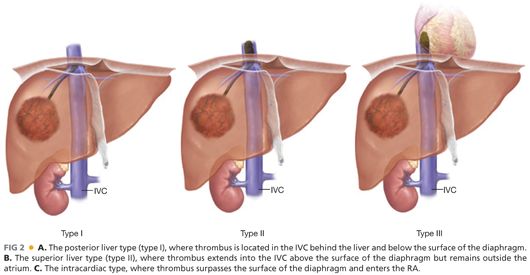

■ Characteristics of inferior vena cava tumor thrombus (IVCTT): IVCTT often spreads from the hepatic veins or hepatic short veins.30–33 IVCTT is clinically classified into three types (FIG 2): (1) the posterior liver type (type I), where TT is located in the IVC behind the liver and below the surface of the diaphragm; (2) the superior liver type (type II), where TT extends into the IVC above the surface of the diaphragm but outside the atrium; and (3) the intracardiac type, where TT surpasses the surface of the diaphragm and enters the RA. The operative plan for patients with IVCTT completely depends on this classification of the IVCTT.

Surgical Positioning

■ The patient is positioned supine with both arms tucked (access to the chest may be required).

■ The patient is prepped from chin to midthigh. The chest should be covered with sterile drapes, if sternotomy is not anticipated, to optimize maintenance of normothermia.

■ The authors advocate placement of central lines in the left jugular vein and left femoral vein. These are the access points for VVB should it be required.

Incision

■ A right subcostal incision with midline extension to the xiphoid process provides excellent exposure and facilitates extension should a sternotomy prove indicated.

■ A fixed retractor is used that is capable of providing adequate exposure. The authors use a Thompson retractor.

TECHNIQUES

HEPATIC NEOPLASM INVASION OF THE INFERIOR VENA CAVA WALL WITHOUT TUMOR THROMBUS

■ The liver is fully mobilized.

■ An umbilical tape is placed around the hepatoduodenal ligament and vessel loops are placed around the right hepatic vein as well as the confluence of the left and middle hepatic veins. Occasionally, lesion location will preclude this control of both veins. The authors advocate being prepared to perform THVE, and associated VVB if indicated, in this setting.

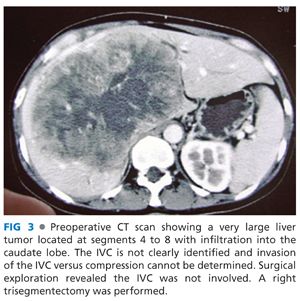

■ Next, assess for IVC invasion versus compression. The underlying pathology will be somewhat predictive of encountering true invasion. HCC most typically will compress, but not invade the IVC (FIG 3). ICC or metastatic adenocarcinomas are more prone to truly invade the IVC.

■ Dissect, control, and divide short hepatic veins working in a caudal to cranial fashion. When the IVC is invaded by a hepatic tumor, the wall becomes pale and stiff. More often than not, there is usually a plane between the tumor and the IVC for separation. Careful identification of this plane may completely avoid injury or need for resection into the IVC.

■ Sometimes, after tumors are stripped from the IVC or the IVC outer membranes are compromised by sharp dissection technique, the thinned IVC wall should be repaired with polypropylene 5-0 sutures ideally placed in the transverse axis to prevent narrowing of the lumen.

■ If the IVC can be fully dissected, resection proceeds as described in other chapters.

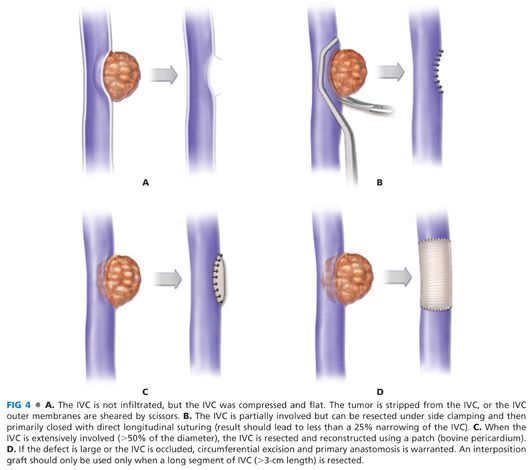

■ If the IVC is invaded, the next step is to determine if the segment is short enough to facilitate IVC resection with control using a side-biting vascular clamp such as a Satinsky clamp (FIG 4). This clamp is most easily placed after the parenchymal transection when the resection specimen can be retracted to elevate the final area of attachment on the IVC. You may not be able to determine the cranial extent of involvement until the liver has been divided.

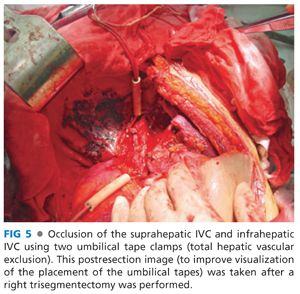

■ Prior to beginning the parenchymal dissection, get control of the suprahepatic and infrahepatic vena cava by circumferentially dissecting them and placing umbilical tapes (FIG 5). Identify and set aside the appropriate vascular clamps you will require should THVE prove indicated. A test clamp of the suprahepatic vena cava should be performed to determine the need for VVB, if THVE is required.

■ Hepatic transection proceeds from superficial to deep tissues with the portal trial clamped. The left index finger should be placed up against the lateral wall of the IVC, and the left thumb is put on the medial/anterior aspect of the IVC. This maneuver provides proprioception for the operative surgeon during the transection.

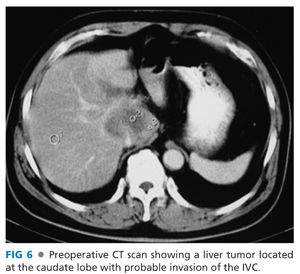

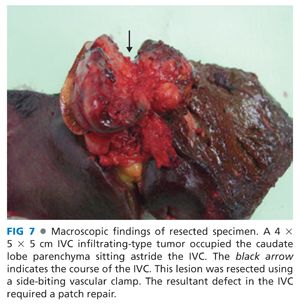

■ To facilitate vascular control for subsequent repair, clamp the IVC with a large Satinsky clamp to provide a margin for sharp resection of the involved segment of the IVC (FIGS 6 and 7).

■ If the segment of IVC involvement proves to be more extensive, proceed with THVE to remove the tumor and repair the IVC.

■ Sharply excise the lesion with a venous margin that ideally is greater than 0.5 cm.

■ Alternatively, the resection can be performed in two steps: to resect and remove the main tumor first, then to clamp the affected part on the IVC wall with Satinsky forceps, cut off the remnant tumor, and finally repair the IVC.

■ Assess whether a patch will be required versus primary repair.

■ Simple, longitudinal closure with 5-0 polypropylene is acceptable unless it results in narrowing of the IVC lumen greater than 25%.

■ Alternatively, if the resection exceeds about half of the circumference, a patch of autologous vein or bovine pericardium can be sewn circumferentially with running 5-0 polypropylene.

■ Reported vein grafts for patch repair include saphenous vein, superficial femoral vein, or left renal vein.

■ If the IVC is either extensively infiltrated or completely obstructed, the IVC should be resected and reconstructed using a graft. During segmental resection, vascular clamps should be placed at both proximal and distal sides of the involved part of the IVC. Umbilical tapes will not provide adequate hemostasis.

■ Defects shorter than 3 cm can often be primarily reapproximated with 5-0 polypropylene.

■ If the defect is longer than 3 cm or primary anastomosis is under undue tension, an interposition graft is warranted.

■ Unfortunately, autologous vein grafts are too small to replace the IVC. The favored material for an IVC interposition graft is stented polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE).14, 34–46 These conduits are available in varying sizes and are inserted using 5-0 polypropylene running suture.

HEPATIC NEOPLASM WITH INFERIOR VENA CAVA TUMOR THROMBUS

■ Surgery selection depends on the level at which TT enters the IVC (FIG 2).

■ In surgical manipulation of HCC with TT, it is critical to avoid squeezing the hepatic veins and the IVC in the process of dissecting the tumor, which may result in TT pulmonary embolism. However, “no-touch” technique is almost impossible in the process of dissecting a large tumor mass, and therefore, it is difficult to prevent TT from falling off completely.

■

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree