Assess cardiac status (angina, arrhythmias, previous MI, BP, ECG, CXR). We assess respiratory function by pulmonary function tests (FVC, FEV1) for all major surgery and any surgery where the patient has symptoms of respiratory problems or a history of chronic airways disease (e.g. asthma).

Arrange an anaesthetic review where there is, for example, cardiac or respiratory comorbidity.

Culture urine, treat active (symptomatic) infection with an appropriate antibiotic, starting a week before surgery, and give prophylactic antibiotics at the induction of anaesthesia.

Consider stopping aspirin and NSAIDs 10 days prior to surgery.

Obtain consent.

Measure haemoglobin and serum creatinine and investigate and correct anaemia, electrolyte disturbance, and abnormal renal function. If blood loss is anticipated, group and save a sample of serum or crossmatch several units of blood, the precise number depending on the speed with which your blood bank can deliver blood, if needed. In our own unit, our policy is (other units may have a different policy) (Box 17.1):

The patient may choose to store their own blood prior to the procedure.

|

Table 17.1 Oxford Urology procedure: specific antibiotic prophylaxis protocol for urological surgery | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Low-risk patients: those <40 undergoing minor surgery (surgery lasting <30min) and no additional risk factors. No specific measures to prevent DVT are required in such patients other than early mobilization. Increasing age and duration of surgery increases the risk of VTE.

High-risk patients: include those undergoing non-major surgery (surgery lasting >30min) who are aged >60.

Active heart or respiratory failure.

Active cancer or cancer treatment.

Acute medical illness.

Age >40y.

Antiphospholipid syndrome.

Behcet’s disease.

Central venous catheter in situ.

Continuous travel >3h up to 4 weeks before surgery.

Immobility (paralysis or limb in plaster).

Inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease/ulcerative colitis).

Myeloproliferative diseases.

Nephrotic syndrome.

Paraproteinaemia.

Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria.

Personal or family history of VTE.

Recent myocardial infarction or stroke.

Severe infection.

Use of oral contraceptive or hormone replacement therapy.

Varicose veins with associated phlebitis.

Inherited thrombophilia.

Factor V Leiden.

Prothrombin 2021A gene mutation.

Antithrombin deficiency.

Protein C or S deficiency.

Hyperhomocysteinaemia.

Elevated coagulation factors (e.g. Factor VIII).

CXR: may be normal or show linear atelectasis, dilated pulmonary artery, oligaemia of affected segment, small pleural effusion.

ECG: may be normal or show tachycardia, right bundle branch block, inverted T waves in V1-V4 (evidence of right ventricular strain). The ‘classic’ SI, QIII, TIII pattern is rare.

Arterial blood gases: low PO2 and low PCO2.

Imaging: CT pulmonary angiogram (CTPA)—superior specificity and sensitivity when compared with ventilation perfusion (VQ) radioisotope scan.

Below-knee DVT: above-knee thromboembolic stockings (AK-TEDs), if no peripheral arterial disease (enquire for claudication and check pulses) + unfractionated heparin 5000U SC 12-hourly.

Above-knee DVT: start a low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) and warfarin and stop heparin when INR is between 2 and 3. Continue treatment for 6 weeks for post-surgical patient; lifelong if underlying cause (e.g. malignancy).

LMWH.

Early mobilization.

AK-TEDs—provide graduated, static compression of the calves, thereby reducing venous stasis. More effective than below-knee TEDS for DVT prevention.5

In unfractionated preparations, heparin molecules are polymerized— molecular weights from 5000-30 000Da. LMWH is depolymerized— molecular weight 4000-5000Da.

IPC boots, which are placed around the calves, are intermittently inflated and deflated, thereby increasing the flow of blood in calf veins.6

Any local leg conditions with which stockings would interfere, such as dermatitis, vein ligation, gangrene, recent skin grafts.

Peripheral artery occlusive disease (PAOD).

Massive oedema of legs or pulmonary oedema from congestive cardiac failure.

Extreme deformity of the legs.

Allergy to heparin.

History of haemorrhagic stroke.

Active bleeding.

Significant liver impairment—check clotting first.

Thrombocytopenia (platelet count <100 × 109/L).

Table 17.2 Pre- and post-operative risks | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

For the first 10kg: 100mL/kg per 24h (= 1000mL).

Class I: up to 750mL of blood loss (15% of blood volume); normal pulse rate (PR), respiratory rate (RR), BP, urine output, and mental status.

Class II: 750-1500mL (15-30% of blood volume); PR >100; decreased pulse pressure due to increased diastolic pressure; RR 20-30; urinary output 20-30mL/h.

Class III: 1500-2000mL (30-40% of blood volume); PR >120; decreased BP and pulse pressure due to decreased systolic pressure; RR 30-40; urine output 5-15mL/h; confusion.

Remember ‘ABC’: 100% oxygen to improve tissue oxygenation.

ECG, cardiac monitor, pulse oximetry.

Insert two short and wide IV cannulae in the antecubital fossa (e.g. 16 G). A central venous line may be required.

Infuse 1L of warm Hartmann’s solution or if severe haemorrhage, then start a colloid instead (e.g. Gelofusin®). Aim for a urinary output of 0.5mL/kg/h and maintenance of BP.

Check FBC, coagulation screen, U & E, and cardiac enzymes.

Cross-match 6U of blood.

Arterial blood gases to assess oxygenation and pH.

Patient identification: confirm you are operating on the right patient by a process of ‘active’ identification (i.e. ask the patient their name, date of birth, and their address to confirm that you are talking to the correct patient).

Ensure you are doing the correct procedure and on the correct side by cross-checking with the notes and X-rays: for lateralized procedures (e.g. nephrectomy, PCNL), the correct side of the operation should be confirmed by cross-checking with the X-rays and with the X-ray report as well as referring to the notes. Where it is possible for the sides of an IVU to be incorrectly labelled, this cannot happen with a CT scan where the location of the liver (right side) and the spleen (left side) provides confirmation of what side is what.

Appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis has been given.

Blood is available, if appropriate.

The patient is safely and securely positioned on the operating table: pressure points padded, not touching metal (to avoid diathermy burns), body straps securely in place.

Dilutional hyponatraemia is the most important—and serious—factor leading to the symptoms and signs. The serum sodium usually has to fall to <125mmol/L before the patient becomes unwell.

Hypertension—due to fluid overload.

Visual disturbances may be due to the fact that glycine is a neurotransmitter in the retina.

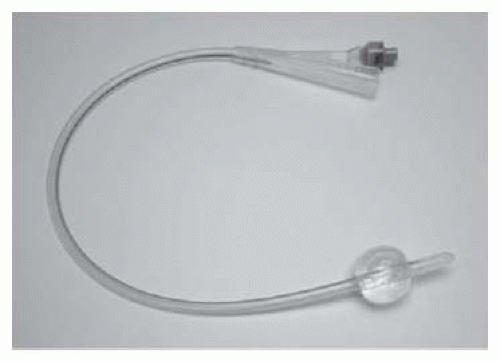

Self-retaining (also known as a Foley, balloon, or 2-way catheter) (Fig. 17.1). An inflation channel can be used to inflate and deflate a balloon at the end of the catheter, which prevents the catheter from falling out.

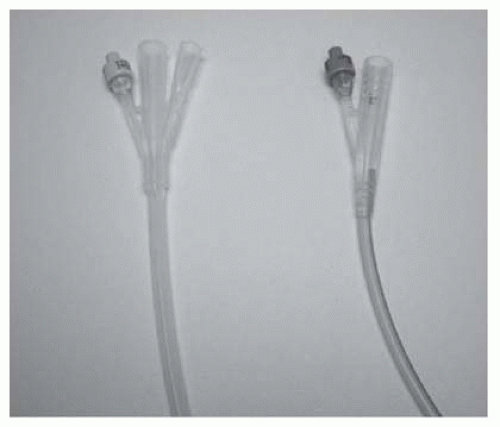

A 3-way catheter (also known as an irrigating catheter). Has a third channel (in addition to the balloon inflation and drainage channels) which allows fluid to be run into the bladder at the same time as it is drained from the bladder (Fig. 17.2).

Relief of obstruction (e.g. BOO due to BPE causing urinary retention— use the smallest catheter that you can pass; usually a 12 Ch or 14 Ch is sufficient in an adult).

Irrigation of the bladder for clot retention (use a 20 Ch or 22 Ch 3-way catheter).

Drainage of urine to allow the bladder to heal if it has been opened (trauma or deliberately, as part of a surgical operation).

Prevention of ureteric reflux, maintenance of a low bladder pressure, where the ureter has been stented (post-pyeloplasty for PUJO).

To empty the bladder before an operation on the abdomen or pelvis (deflating the bladder gets it out of harm’s way).

Monitoring of urine output post-operatively or in the unwell patient.

For delivery of bladder instillations (e.g. intravesical chemotherapy or immunotherapy).

To allow identification of the bladder neck during surgery (e.g. radical prostatectomy, operations on or around the bladder neck).

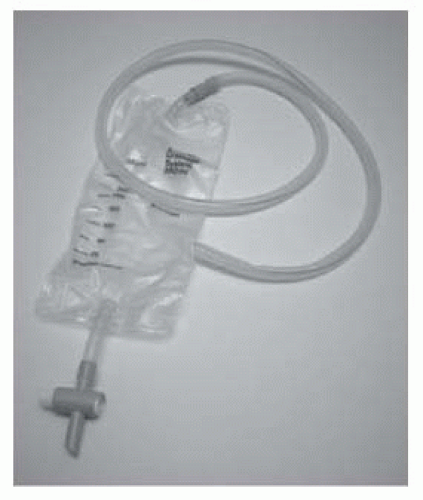

Tube drains (e.g. a Robinson’s drain; Figs. 17.3 and 17.4): provide passive drainage (i.e. no applied pressure). Used to drain suture lines at a site of repair or anastomosis of the urinary tract. Avoid placing the drain tip on the suture line as this may prevent healing of the repair. Suture it to adjacent tissues to prevent it from being dislodged.

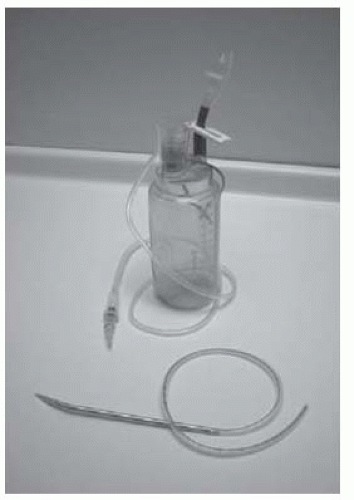

Suction drains (e.g. Hemovac®; Figs. 17.5 and 17.6): provide active drainage (i.e. air in the drainage bottle is evacuated, producing a negative pressure when connected to the drain tube to encourage evacuation of fluid). Used for the prevention of accumulation of blood (a haematoma) in superficial wounds. Avoid in proximity to a suture line in the urinary tract—the suctioning effect may encourage continued flow of urine out of the hole, discouraging healing.

Try inflating the balloon with air or water—this can dislodge an obstruction.

Leave a 10mL syringe firmly inserted in the balloon channel and come back an hour or so later.

Try bursting the balloon by overinflation.

Cut the end of the catheter off, proximal to the inflation valve—the valve may be ‘stuck’ and the water may drain out of the balloon.

In the female patient, introduce a needle alongside your finger into the vagina and burst the balloon by advancing the needle through the anterior vaginal and bladder wall.

In male patients, balloon deflation with a needle can also be done under USS guidance. Fill the bladder with saline using a bladder syringe so that the needle can be introduced percutaneously and directed towards the balloon of the catheter under USS control.

Pass a ureteroscope alongside the catheter and deflate the balloon with the rigid end of a guidewire or with a laser fibre (the end of which is sharp).

Fig. 17.5 A Redivac suction drain showing the drain tubing attached to the needle used for insertion and the suction bottle. |

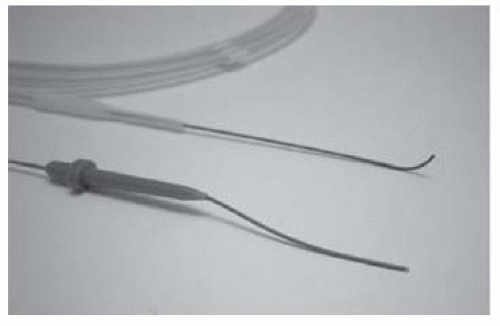

Fig. 17.8 Examples of straight-tip and angled-tip guidewires.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|