Chapter 12 Ariana L. Smith, MD; Eric S. Rovner, MD The World Health Organization estimates that there are 130,000 new cases of urogenital fistula per year worldwide. This number likely underestimates the true incidence because many patients in developing countries lack access to care. A fistula represents an extra-anatomic communication between two or more epithelial or mesothelial lined body cavities or the skin surface. Although most fistulas in the industrialized world are iatrogenic, they may also occur as a result of parturition (the most common etiology worldwide), congenital anomalies, malignancy, inflammation and infection, radiation therapy, surgical or external tissue trauma, foreign bodies, ischemia, and a variety of other processes. The potential exists for fistula formation between a portion of the urinary tract (i.e., kidney, ureters, bladder, urethra) and virtually any other body cavity, including the reproductive organs, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, chest (pleural cavity), lymphatics, vascular system, genitalia, and skin. The presenting signs and symptoms are variable and depend to a large degree on the involved organs, the presence of underlying urinary obstruction or infection, the size of the fistula, and associated medical conditions such as malignancy. Treatment of urinary fistula depends on several factors, including its location, size, etiology (malignant or benign), and surrounding tissue quality. Vesicovaginal fistula (VVF) is the most common acquired fistula of the urinary tract. The most common cause of VVF differs in various parts of the world. b. The incidence of fistula after hysterectomy is estimated to be approximately 0.1% to 0.2%. The injury rate to the urinary tract is much higher than this because most injuries do not result in fistula. Patients who develop a VVF are more likely to have a large cystotomy, greater tobacco use, larger uterine size, and more operative blood loss. c. Other causes of VVF in the industrialized world include malignancy, pelvic radiation, and obstetrical trauma, including forceps lacerations and uterine rupture. 2. In the developing world where routine obstetrical care may be limited, VVFs most commonly occur as a result of prolonged obstructed labor with resulting pressure necrosis and tissue ischemia to the pelvic floor. The anterior vaginal wall, trigone, and urethra generally experience the greatest direct pressure from the trapped fetus. In some instances, VVF may result from the use of forceps or other instrumentation during operative delivery. b. The constellation of problems resulting from obstructed labor is not limited to VVF and has been termed the obstructed labor injury complex and includes varying degrees of each of the following: Urethral loss, stress incontinence, hydroureteronephrosis, renal failure, rectovaginal fistula, rectal atresia, anal sphincter incompetence, cervical destruction, amenorrhea, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), secondary infertility, vaginal stenosis, osteitis pubis, and foot drop. c. In sub-Saharan Africa the incidence rate of obstetric VVF has been estimated at 10.3 per 100,000 deliveries. b. Patients may also complain of recurrent cystitis, perineal skin irritation caused by constant wetness, vaginal fungal infections, or rarely pelvic pain. When a large VVF is present, patients may not void at all and simply have continuous leakage of urine into the vagina. c. VVF following hysterectomy or other surgical procedures may present on removal of the urethral catheter or may present 1 to 3 weeks later with urinary drainage per vagina. 1) VVFs resulting from hysterectomy are usually located high in the vagina at or just anterior to the vaginal cuff (Figure 12-1). d. VVF resulting from radiation therapy may not present for months to years following completion of radiation. These tend to represent some of the most challenging reconstructive cases in urology because of the size, complexity, and the associated voiding dysfunction caused by radiation effects on the bladder. The tissue ischemia that results from radiation therapy may involve the surrounding tissues, limiting reconstructive options. 2. Physical examination b. Palpate for masses or other pelvic pathology, which may need to be addressed at the time of fistula repair. c. An assessment of inflammation surrounding the fistula is necessary because it may affect timing of the repair. d. The presence of a VVF may be confirmed by instilling vital blue dye or sterile milk into the bladder per urethra and observing for discolored vaginal drainage. 3. Urine culture and urine analysis 4. Cystoscopy and possible biopsy of the fistula tract are performed if malignancy is suspected. b. The presence of foreign bodies, including suture material, mesh, and/or bladder calculi, should be assessed. 5. Voiding cystourethrography 1) Assesses for vesicoureteral reflux. 2) Examines for multiple fistulas including urethrovaginal fistula. 3) Assesses size and location of fistula. 6. Intravenous urography (IVU), computed tomography urography (CTU), and/or retrograde pyeloureterography b. Contrast material in the vagina, air in the bladder, and bladder wall thickening are signs suggestive of the presence of a fistula. 7. Cross-sectional pelvic imaging (magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]/computed tomography [CT]) if malignancy is suspected. b. Fulguration of the fistula tract with electrocautery followed by catheter drainage has been shown to have some efficacy in small (less than 5 mm), uncomplicated fistulas. c. Adjuvant measures such as fibrin glue have been reported in small patient series in conjunction with fulguration and catheter drainage as a “plug” in the fistula and as “scaffolding” to allow the ingrowth of healthy tissue. 2. Surgical management a. Success rates approach 90% to 98% regardless of surgical approach. b. Adherence to basic surgical principles is essential to achieve successful repair of all urinary fistulas (Table 12-1). Table 12-1 Principles of Vesicovaginal Fistula Repair 1. Adequate exposure of the fistula tract with debridement of devitalized and ischemic tissue 2. Removal of involved foreign bodies or synthetic materials from region of fistula if applicable 3. Careful dissection and/or anatomic separation of the involved organ cavities 4. Watertight closure 5. Use of well-vascularized, healthy tissue flaps for repair (atraumatic handling of tissue) 6. Multiple layer closure 7. Tension-free, nonoverlapping suture lines

Urinary Fistula

Vesicovaginal fistula

General considerations

Etiology

Presentation

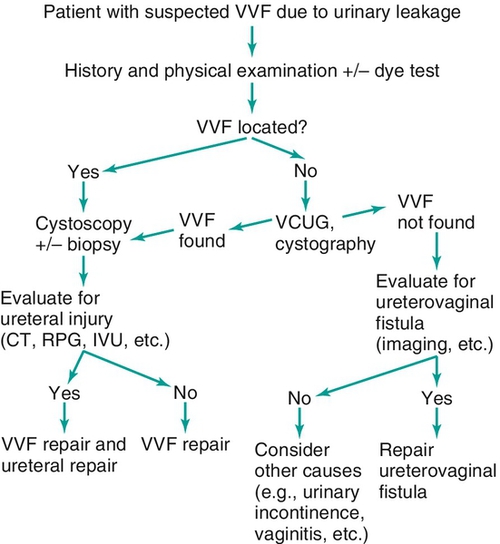

Evaluation (figure 12-2)

Therapy

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Urinary Fistula

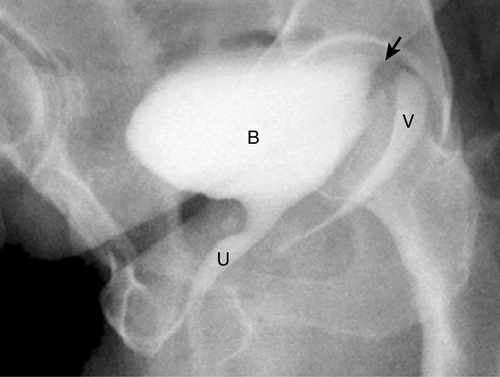

Figure 12-1 Voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) demonstrating a VVF high at the level of the vaginal cuff in a patient following hysterectomy. The arrow demonstrates the fistula tract (not well seen). B, urinary bladder; U, urethra; V, vagina.

Figure 12-2 Algorithm for diagnosis of vesicovaginal fistula (VVF).