ability to obtain meaningful data is compromised. Most of the information, therefore, has been accumulated from Western countries, where the diseases are relatively prevalent. In the United States, however, IBD is not a reportable condition.

|

colitis had a positive history, and 35% of those with Crohn’s disease had a positive family history for IBD.

|

with that of the infectious dysenteries.353 An exception is that of cytomegalovirus infection, which has been shown to complicate ulcerative colitis in immunocompromised patients, such as individuals with AIDS.761

TABLE 29-1 Features of Nonspecific Inflammatory Bowel Disease | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

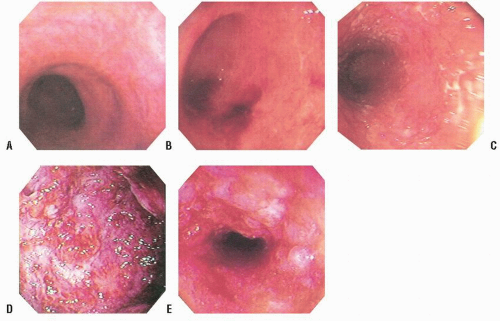

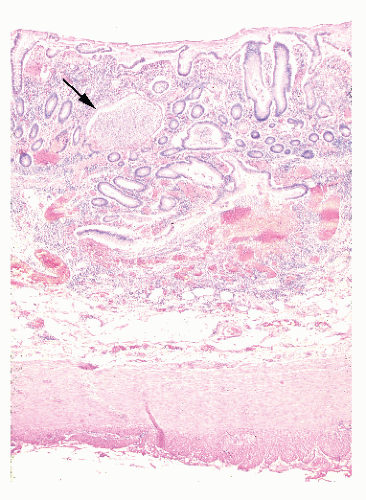

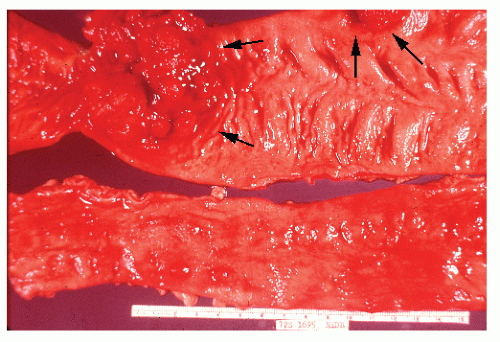

dentate line cephalad to the limit of the inflammatory reaction is consistent with ulcerative proctitis or proctosigmoiditis, depending on the extent of involvement (Figure 29-1). In individuals with treated ulcerative colitis, the finding of rectal sparing or patchiness should not necessarily alter the diagnosis to Crohn’s disease.54 If the patient’s symptoms are appropriate to the endoscopic findings, treatment can be initiated without further contrast study or colonoscopy. Conversely, if the patient’s disease extends beyond the limit of the endoscopic procedure performed, it will be necessary at some point to undertake total colonic evaluation.

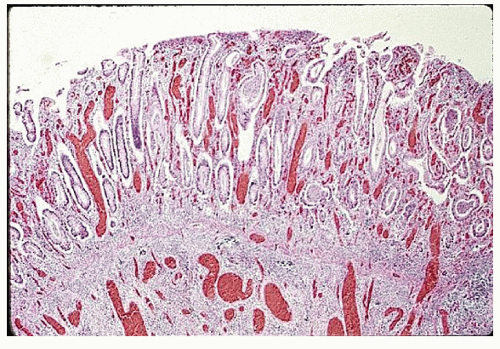

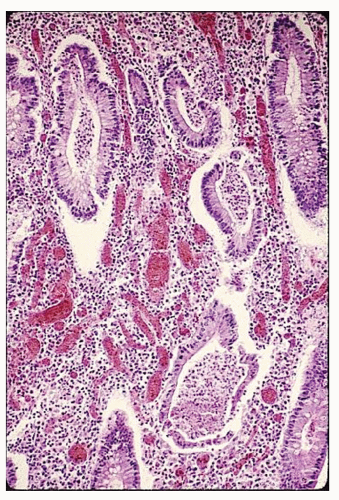

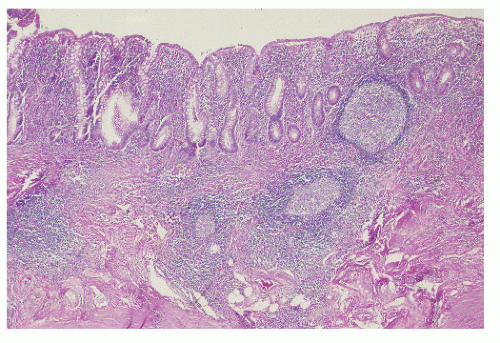

syndrome, and, of course, the differentiation between the two nonspecific IBD conditions, themselves—ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.727 Biopsy may be helpful because histologic changes suggestive of Crohn’s disease in particular may be apparent. Up to 20% of such patients may exhibit granulomas (see Figure 30-2). In patients with ulcerative colitis, rectal biopsy is extremely important for recognizing dysplasia, especially in those with long-standing disease (see Relationship to Carcinoma).

the need for surgery. Furthermore, the high dose of steroids often used in the treatment of toxic megacolon may mask abdominal signs.

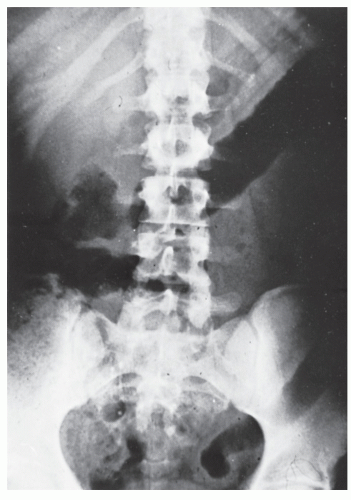

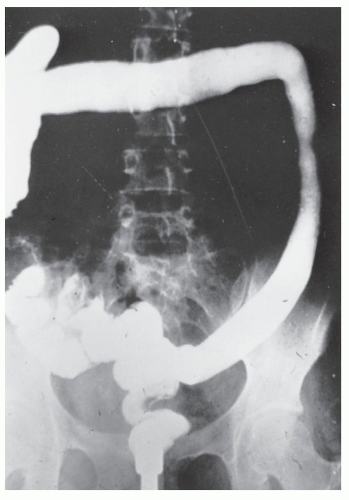

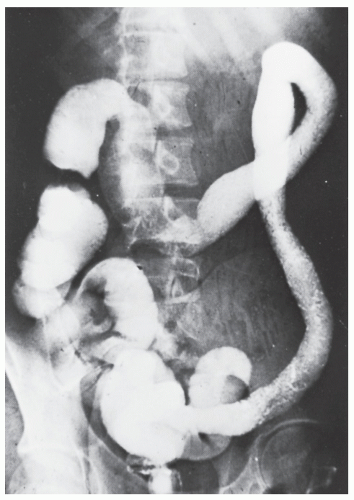

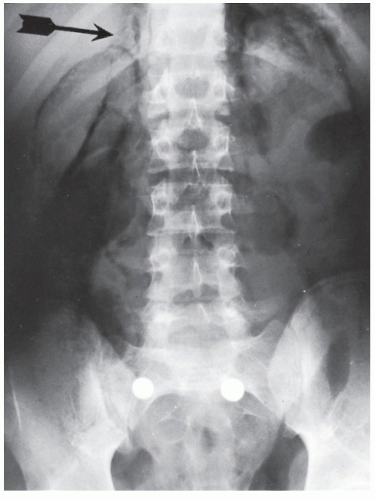

FIGURE 29-5. Edema of the bowel wall in acute ulcerative colitis; flocculation of barium caused by mucus (fuzzy appearance) and thumbprinting in the region of the splenic flexure. |

to reduce the frequency of repeated colonoscopic or barium enema studies in patients already known to harbor IBD.259

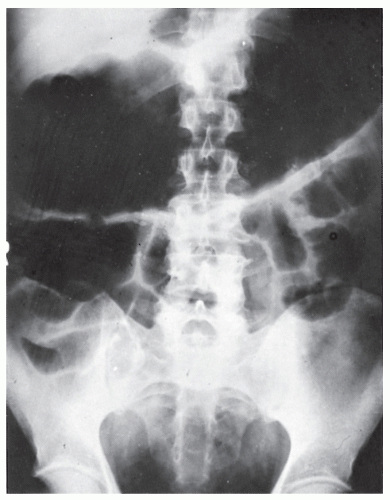

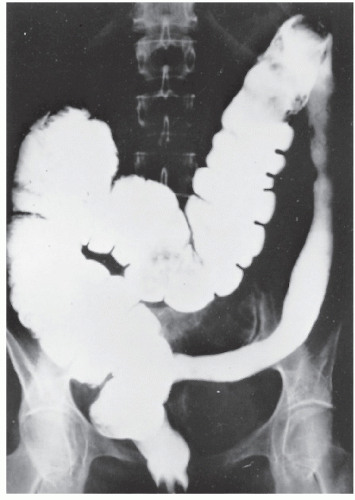

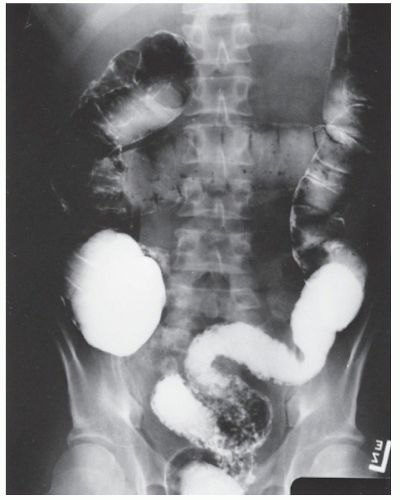

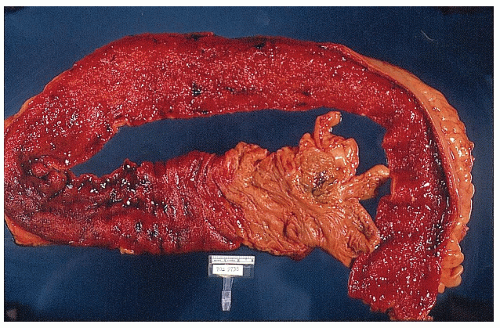

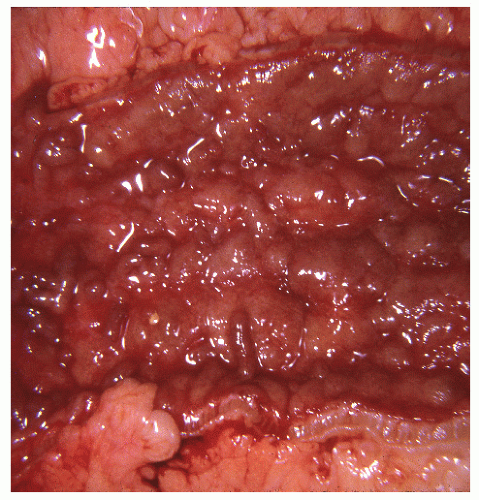

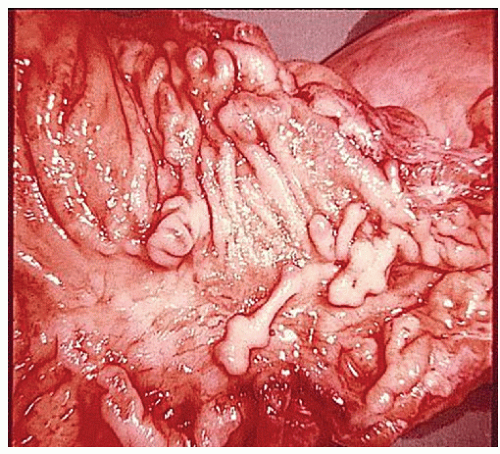

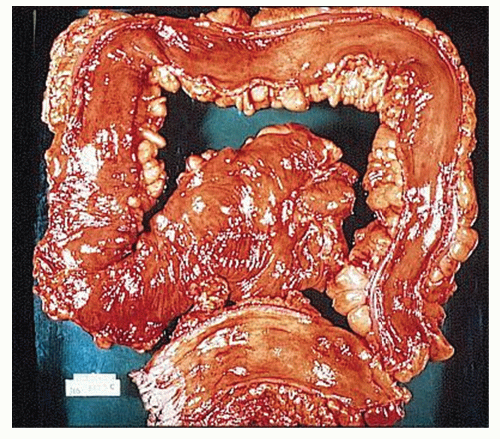

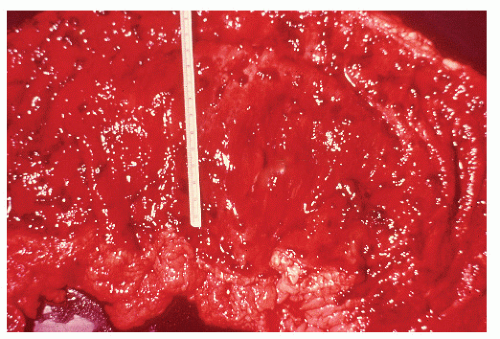

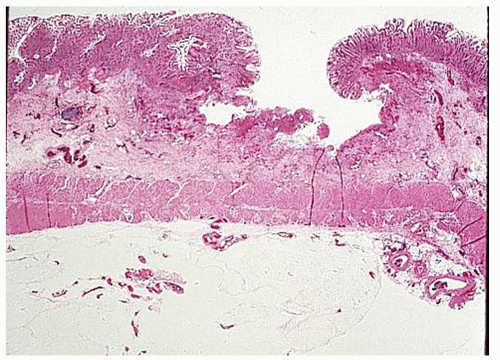

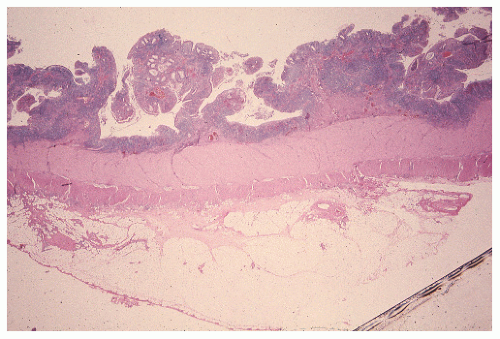

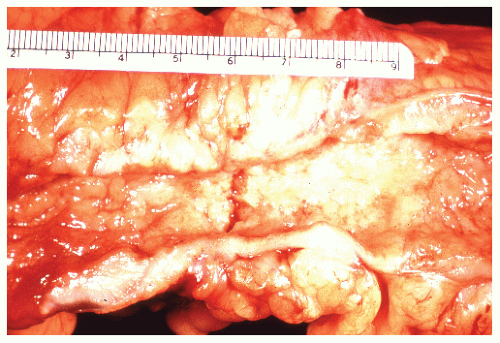

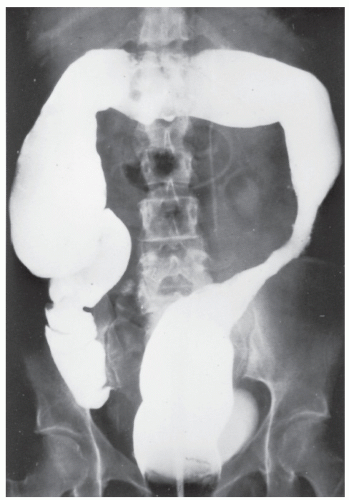

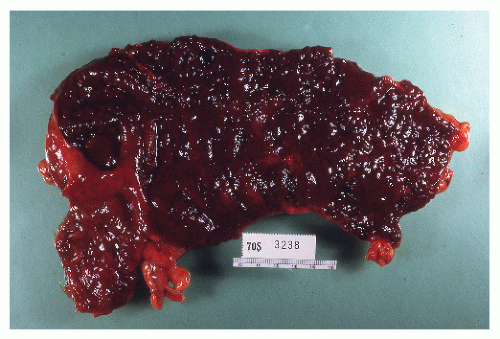

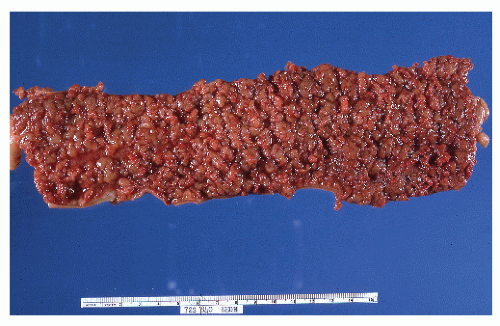

always with continuity of involvement to the proximal extent of the disease process (Figure 29-12). Characteristically, ulcerative colitis tends to involve the bowel more severely in a distal location than proximally. Despite extensive inflammatory reaction, the bowel wall retains its normal thickness (Figure 29-12). The results of the confluence of numerous ulcers are the longitudinal furrows of denuded mucosa that alternate with islands of heaped-up mucosa, the so-called pseudopolyps (Figures 29-13,29-14 and 29-15). Pseudopolyps are inflammatory polyps, not neoplastic lesions. These are seen during a quiescent phase of ulcerative colitis and are a later manifestation of this condition. They may be confused with familial polyposis (see Chapter 22), but the absence of normal mucosa between these polyps suggests the correct diagnosis.

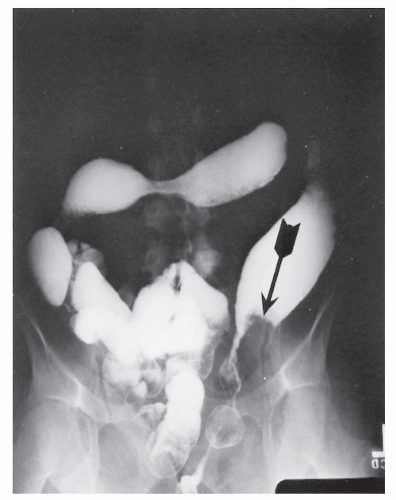

FIGURE 29-14. Extensive pseudopolyps in active ulcerative colitis. Note the relative uniformity of the polyps in comparison with the varied sizes seen in familial polyposis (see Chapter 22). (From Corman ML, Veidenheimer MC, Nugent FW, et al. Diseases of the Anus, Rectum and Colon. Part II: Nonspecific Inflammatory Bowel Disease. New York, NY: Medcom; 1976.) |

these circumstances, the physician may be lulled into a false sense of security because the patient’s symptoms are often minimal. It is unlikely that someone will experience discharge of mucus, diarrhea, or bleeding if no inflamed mucosa is present. It is this individual who is particularly susceptible to the development of carcinoma (see Relationship to Carcinoma).

(pANCA) are present in up to 86% of patients with ulcerative colitis.655 Theoretically, this autoimmunity may represent a possible pathogenetic mechanism for the development of ulcerative colitis. A set of marker antibodies is available for the screening and differential diagnosis of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease (Prometheus Laboratories, Inc., San Diego, CA). Proven applications of this technology include the following:

as an adjunct to clinical and tissue pathology in the differential diagnosis of IBD

confirmation of the correct diagnosis before surgery

identification of those patients with left-sided ulcerative colitis that may be resistant to treatment

identification of those patients prone to the development of pouchitis following ileal pouch-anal anastomosis

general population (12%).346 Those whose condition was in remission at the time of conception had a normal pregnancy, with the disease remaining quiescent in most individuals. However, active disease at the time of conception tended to inhibit remission despite therapy.346 In studies specifically in women with Crohn’s disease, pregnancy entailed no increased risk for exacerbation of the bowel inflammation.540,784 However, an increased risk for premature delivery and spontaneous abortion has been observed in those with active disease or in whom resection is required.

in the second. Colorectal cancer caused 14% of the deaths in patients with ulcerative colitis, three times more often than in persons with Crohn’s disease. Excluding cancer, only two deaths were directly attributable to ulcerative colitis, both occurring within the first 2 years after diagnosis.544

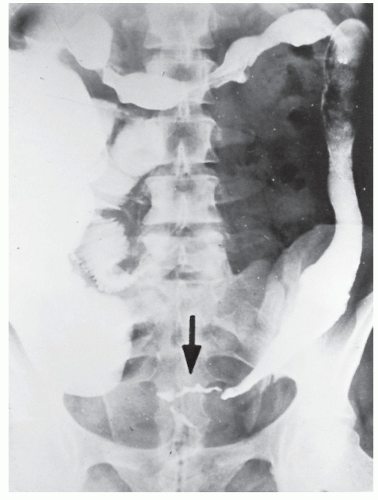

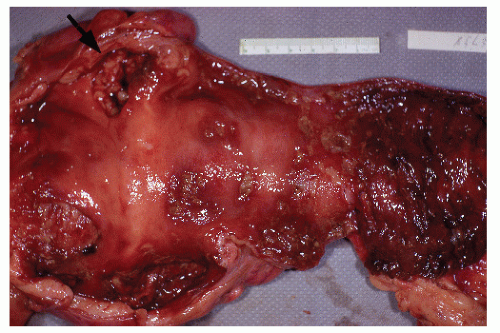

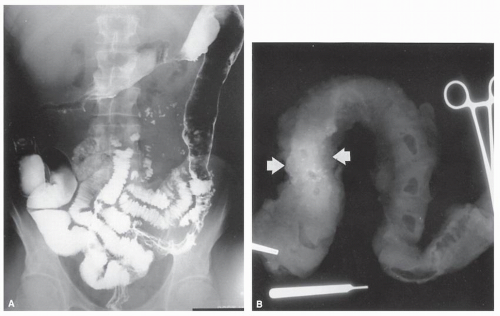

colleagues reported that the rectum was the most common site of involvement and that this was more noticeable in men than in women.623 In their study, more than 40% of the cancers were found in the rectum, and approximately 25% of patients had multiple tumors. It is certainly clear that multicentricity of the cancers is a frequently reported phenomenon (Figure 29-27).

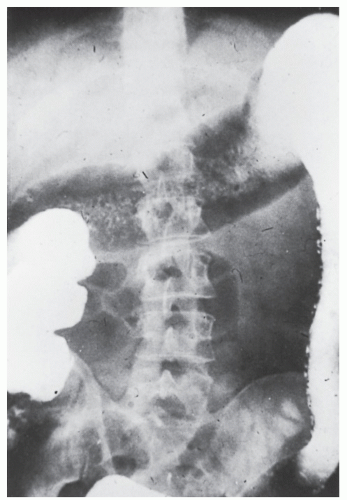

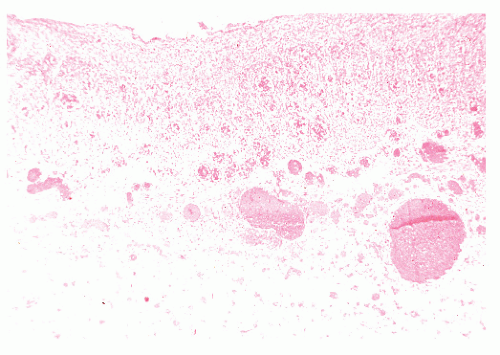

must be presumed to have a carcinoma until it can be proved otherwise (Figures 29-31,29-32 and 29-33). The presence of a stricture in a patient with ulcerative colitis is an indication for operative intervention. Lashner and colleagues demonstrated that of 15 patients with strictures, 11 had dysplasia and 2 were found to have cancer on colonoscopy/biopsy.385 An additional 4 patients were found to have carcinomas at the stricture site at the time of colectomy.

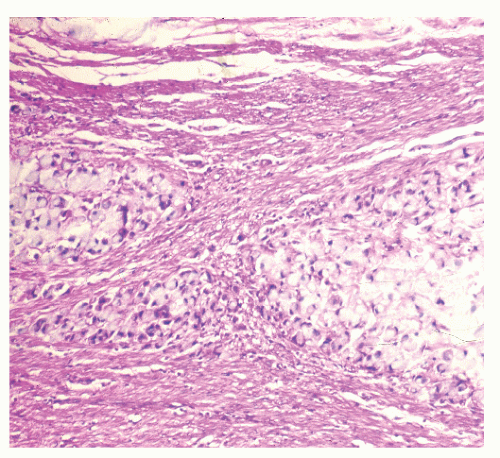

FIGURE 29-30. Signet-ring cell carcinoma infiltration of the muscularis propria in a patient with ulcerative colitis. (Original magnification × 600.) |

Preservation of crypt architecture

Nuclear stratification, but not reaching the luminal surface

Nuclear crowding and hyperchromasia

Mitoses in upper portion of crypt

Usually, moderate diminution of goblet cell mucin

Distortion of crypt architecture with branching and lateral buds

Nuclear abnormalities as in mild dysplasia, but stratification reaching luminal surface

Usually, depletion of goblet cell mucin

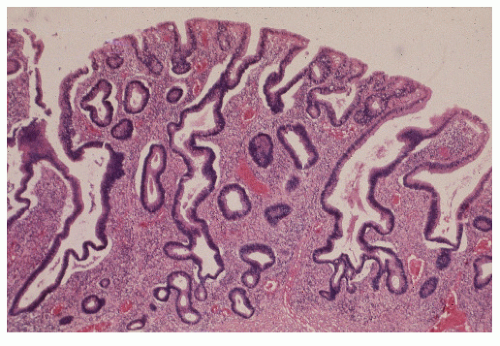

More marked distortion of crypt architecture, frequently with villous configuration of surface epithelium

Nuclear abnormalities as in moderate dysplasia, but with loss of polarity frequently present

Frequently, presence of “back-to-back” glands

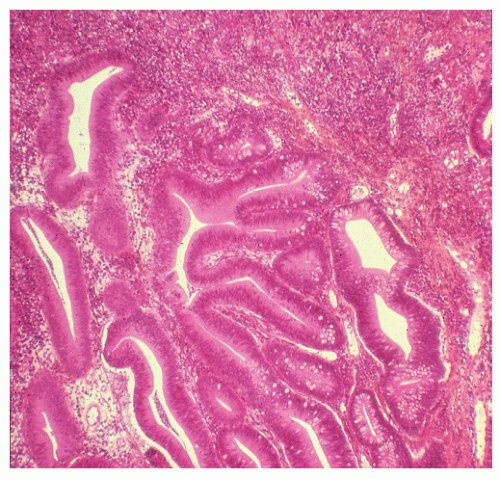

FIGURE 29-34. Moderate dysplasia in a patient with ulcerative colitis. Note the loss of polarity and decreased mucus production. (Original magnification × 80; courtesy of Rudolf Garret, MD.) |

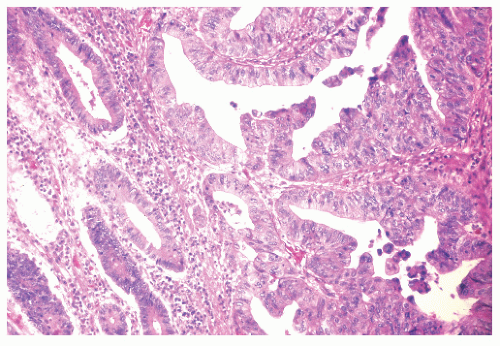

FIGURE 29-35. Moderate dysplasia in ulcerative colitis. Loss of polarity and proliferation of epithelial cells. (Original magnification × 260; courtesy of Rudolf Garret, MD.) |

demonstrated in their 20-year surveillance program of 143 patients with ulcerative colitis that primary sclerosing cholangitis (see Chapter 30) is an independent risk factor for the development of dysplasia or cancer, especially in the proximal colon.424

is another. However, until a better alternative is available, one should continue to recommend the protocol as outlined, with the performance of flexible sigmoidoscopy in alternate years.

is approximately 15%.144 Patients with extensive disease (macroscopic disease proximal to the splenic flexure) are more likely to develop acute severe colitis.

UC, comparable efficacy to that of prednisolone in inducing remission was observed. However, improvement in endoscopic and histologic scores was superior in the prednisolone group.433 Therefore, oral budesonide has not been routinely used in treating UC.

with corticosteroids and/or 6-MP/AZA (ACT 1) or with UC refractory to at least one standard therapy (ACT 2), are the landmark studies evaluating the efficacy of IFX.640 In ACT 1, the clinical response to IFX at 8 weeks was 69% for 5 mg/kg dosing and 61% for 10 mg/kg dosing versus 37% in the placebo group (P < .001), and similar response rates were found at 8 weeks in ACT 2. In both studies, patients who received IFX were more likely to have a clinical response at week 30, and in ACT 1, more patients who received IFX had a clinical response at week 54. Endoscopic remission, which has been of interest as an end point, was also seen in more than 50% of the IFX-treated groups in ACT 1 at 30 and 54 weeks. Subsequently, a follow-up study was done to evaluate health-related QOL in patients treated with IFX to see whether improved clinical response translated to improvement in QOL. Substantially improved QOL was sustained through 1 year with maintenance therapy.162 However, the influence on the risk of colectomy was not evaluated until recently. In a published follow-up of ACT 1 and 2 studies evaluating colectomy rates, the cumulative incidence of colectomy in patients treated with IFX through 54 weeks was 10%.656 This compared with 17% for the patients in the placebo group. However, those enrolled in the study had moderate-to-severe UC who had not received intravenous corticosteroid within 2 weeks and were judged unlikely to require colectomy within 12 weeks. Hence, the reduction in risk cannot be entirely attributed to IFX.656

TABLE 29-2 U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Data on Fetal Risk | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

found that women with CD exposed to corticosteroids and AZA/6-MP were more likely to have preterm birth (12.3% and 25.0%, respectively), compared with non-IBD controls (6.5%).546 Congenital anomalies were also more prevalent among AZA/6-MP-exposed cases compared with the reference group (15.4% vs. 5.7%), with an odds ratio of 2.9 (95% CI, 0.9-8.9).103 Finally, the largest single-center study to date studied 189 women who were exposed to AZA during pregnancy and compared them with 230 women who did not take any teratogenic medications during pregnancy.574 The rate of major malformations did not differ between groups.208 The rate was 3.5% for AZA and 3.0% for the control group (P = .775; OR = 1.17). Thus, the conflicting reports in the literature suggest that the decision on the use of 6-MP/AZA during pregnancy should be based on a case-by-case basis.

Hospitalization

Intravenous corticosteroids, 300 mg/day hydrocortisone, 48 mg/day methylprednisolone, or adrenocorticotropic hormone, for 7 to 10 days, if refractory to maximum doses of oral prednisone, 5-ASAs, and topical agents or if presenting with toxicity

If no improvement after 7 to 10 days, administer intravenous cyclosporine, 4 mg/kg/day, or refer for surgery

Adding 6-MP enhances long-term remission

equal importance is the fact that steroids are ineffective in maintaining remission. Their value is in short-term use or in induction therapy.244

repeated or frequent relapses

prolonged, fruitless attempts at tapering

maintenance of remission

delaying introduction

underdosing

early suspension or discontinuance

giving it to people who do not need it

giving it to people who cannot benefit from it (bowel obstruction and internal fistulas)

failure to have an exit strategy (the need to administer antimetabolites concomitantly)

Does one have the luxury of time, such as with fulminating or hemorrhagic disease?

Is the colon really worth saving?

Where does one go after its use? This drug must be used as a bridge to other, safer regimens.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree