Miscellaneous Colitides

Marvin L. Corman

Albert O. Kwon

This chapter addresses a number of inflammatory conditions of the bowel that, in general, are either infectious or noninfectious. The two conditions that have been discussed in previous chapters, ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, have been excluded. The common denominator for all of these diseases is an association with the symptom of diarrhea. The great majority of colitides are infectious in nature and are frequently the result of ingestion of contaminated food or water. Enteric diseases can also be sexually transmitted, especially through anal intercourse. This is a particular issue in immunosuppressed and HIV patients (see Chapter 10).

Although diarrheal disease is still one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality, especially among children in the developing world, it is not an insignificant source of morbidity in Western countries due to the ubiquitous nature of travel and immigration. In the United States, adults experience an average of 4 episodes per year, and children experience 7 to 15 episodes by age 5.218 Certainly, in elderly individuals or those who are immunocompromised, the potential for mortality is increased. Although it is indeed true that most diarrheal conditions are self-limiting, the surgeon must always be alert to the fact that even an acute onset of diarrheal disease may be the initial presentation of an underlying disorder that mandates thorough gastrointestinal investigation.317

▶ NONINFECTIOUS COLITIDES

I am poured out like water, and all my bones are out of joint; my heart is like wax; it is melted in the midst of my bowels.

—Psalm 22:14

Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis (Eosinophilic Colitis)

Primary eosinophilic gastroenteritis is a disorder that selectively affects the gastrointestinal tract. First described in 1937 by Kaisjer, it is characterized by an eosinophilpredominant chronic inflammatory process of unknown etiology. The eosinophilia is present not only in the peripheral blood but also in the intestinal tissue.276 However, it has been reported that up to 23% of individuals do not present with peripheral eosinophilia.223 With approximately 75% of affected individuals found to have an allergic or atopic history, such an association has been suggested, but it has yet to be proven.219,223 However, it is known that the expansion and tissue distribution of eosinophils are regulated by IL-5 and eotaxin 1.263 Furthermore, eosinophilic gastroenteritis has strong genetic and allergic components and presents immunopathogenic features similar to those of other allergic disorders, such as asthma.

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis can potentially affect any portion of the gastrointestinal tract. This can lead to eosinophilic esophagitis, eosinophilic gastritis, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, and eosinophilic colitis. The gastric antrum and the proximal small intestine are most frequently involved, whereas the colon is a rare location for the condition. Perianal disease has also been reported.176 Eosinophilic colitis has a bimodal distribution, primarily affecting neonates and young adults.

The three major clinical patterns have been described based on the level of eosinophilic infiltration within the intestinal wall. The extent of disease corresponds to the clinical signs and symptoms of eosinophilic colitis. Primary mucosal disease is associated with enteric protein loss, diarrhea, and malabsorption. Predominant muscle layer disease

is characterized by obstructive symptoms as well as bowel thickening and may result in volvulus, intussusception, or perforation. Primary subserosal disease classically presents with eosinophilic ascites.35,171,223,235 The most common presenting symptoms are abdominal pain and change in bowel habits. Nausea, vomiting, weight loss, and rectal bleeding are also frequently noted.

is characterized by obstructive symptoms as well as bowel thickening and may result in volvulus, intussusception, or perforation. Primary subserosal disease classically presents with eosinophilic ascites.35,171,223,235 The most common presenting symptoms are abdominal pain and change in bowel habits. Nausea, vomiting, weight loss, and rectal bleeding are also frequently noted.

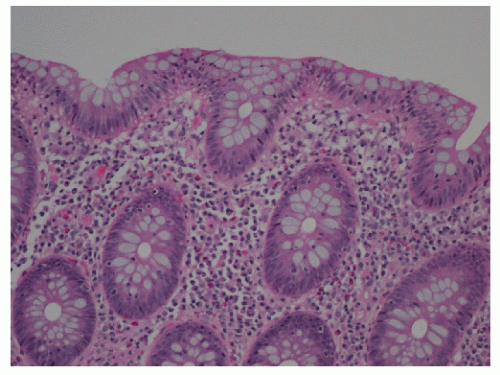

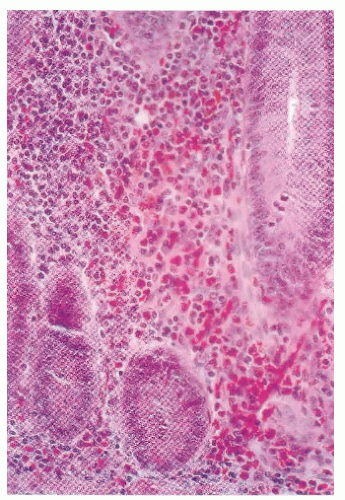

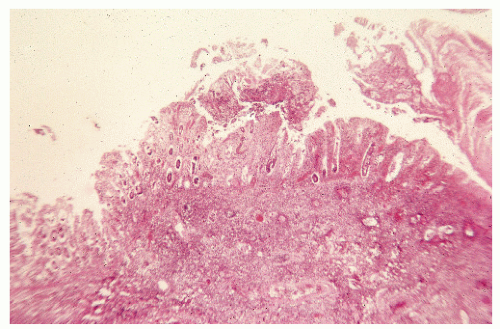

Tissue eosinophilia is a common feature of eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Although eosinophiles are recognized manifestation in numerous gastrointestinal conditions, especially Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, there is no comparison with the massive infiltration present in eosinophilic gastroenteritis and colitis.219 When the condition occurs in the colon, it may radiologically mimic tuberculosis, amebiasis, or Crohn’s disease.276 Based on the few cases reported thus far, the proximal colon seems to have a greater predilection for involvement. Colonoscopic evaluation may reveal changes from erythema and friability, to granularity and narrowing.235 Tedesco and colleagues suggested that eosinophilic ileocolitis may be more common than originally thought, and postulated that biopsy and counting of high-power microscopic fields for eosinophils may be a useful means for distinguishing eosinophilic colitis from that of Crohn’s disease (Figure 33-1).302 Eosinophilic colitis is largely a diagnosis of exclusion. In addition to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), the differential diagnosis should include infectious colitides, such as helminthiasis and amebiasis (see later), systemic hypereosinophilia syndrome, milk protein colitis, vasculitis, and allergic gastroenteropathy.35 Evaluation of IgE levels may help in determining the possibility of allergen involvement. Moreover, immunohistochemical analysis of intestinal eosinophil activation in patients with eosinophilic gastroenteritis suggests that the eosinophil cationic protein stored in eosinophil granules and secreted by activated eosinophils may be a tissue marker for eosinophilic gastroenteritis.28 However, the combination of histologic and clinical patterns is the mainstay for the diagnosis of inflammatory conditions of the colon.47 Although diagnostic criteria have been established for eosinophilic esophagitis, there has yet to be a consensus reached for eosinophilic colitis. Many investigators have used 20 eosinophils per high power field as being diagnostic. It is important to note, however, that the amount of eosinophils present varies depending on the location within the colon, ranging significantly above and below the aforementioned threshold.223

FIGURE 33-1. Eosinophilic enteritis. Intense inflammatory infiltration by eosinophils is seen within the mucosa and submucosa of the small bowel. (Original magnification × 330.) |

Prognosis is generally good, with clinical, hematologic, roentgenographic, and histologic improvement occurring spontaneously (usually in children) or with corticosteroid therapy.125 Commonly, symptoms will resolve within 2 weeks on steroid treatment. However, recurrence is not infrequent. Novel therapeutic approaches to the management of eosinophilic gastroenteritis are currently being assessed, including treatment with newer antihistamines, leukotriene receptor antagonists, and monoclonal antibodies, such as anti-IL-5 (mepolizumab) and anti-IgE (omalizumab).108,223 However, resection of the involved bowel may be required for unremitting symptoms or to exclude another diagnosis.219

Microscopic Colitis: Lymphocytic Colitis and Collagenous Colitis

Microscopic colitis is an inflammatory condition that was initially described in 1976 by Lindström and colleagues.183 It is characterized by chronic, watery diarrhea and grossly normal appearing colonic mucosa on endoscopic examination, with inflammation evident only on microscopic examination. Terminology for the disease has evolved as further investigation has allowed the disease to be more well defined. At present, it is widely accepted that microscopic colitis consists of two subtypes: lymphocytic colitis and collagenous colitis. Although the clinical manifestations are similar, the subtypes can be differentiated based on the presence of intraepithelial lymphocytosis and subepithelial collagen deposition, respectively.274

The actual incidence of microscopic colitis is unknown because it is a poorly reported condition. A study from Sweden by Olesen and colleagues224 noted an increasing incidence of microscopic colitis over the past decades from 1.8 per 100,000 to 6 per 100,000 inhabitants. The authors concluded that the incidence of microscopic colitis is higher than previously described and is as common as Crohn’s disease in Örebro, Sweden. Microscopic colitis was diagnosed in 10% of patients with nonbloody diarrhea and up to 20% of those individuals who were older than age 70 years. There is no association of microscopic colitis with an increased risk of colorectal cancer.186 The incidence of microscopic colitis within the United States was recently investigated in a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Over the duration of the study, investigators also reported an increasing incidence from 1.1 to 19.6 cases per 100,000 person-years. A positive association with older age was noted as well.234 In a Canadian population-based study conducted by Williams and colleagues, the authors found that individuals aged 65 and older were five times more likely to have the disease, and an increased risk was found in women for both subtypes of microscopic colitis.324

A definitive cause of microscopic colitis has yet to be determined. Reports in the literature have described a correlation between the disease and certain medications,

such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). However, no causal relationship has been established.299 With respect to disease associations, links to autoimmunity are widely accepted, and an increased prevalence of microscopic colitis among patients with celiac disease has been described.57,224 Moreover, Koskela and colleagues recently determined that HLA DR3-DQ2 (already linked to celiac disease) and TNF2 allele carriage (associated with autoimmunity) were also associated with both subtypes of microscopic colitis.170

such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). However, no causal relationship has been established.299 With respect to disease associations, links to autoimmunity are widely accepted, and an increased prevalence of microscopic colitis among patients with celiac disease has been described.57,224 Moreover, Koskela and colleagues recently determined that HLA DR3-DQ2 (already linked to celiac disease) and TNF2 allele carriage (associated with autoimmunity) were also associated with both subtypes of microscopic colitis.170

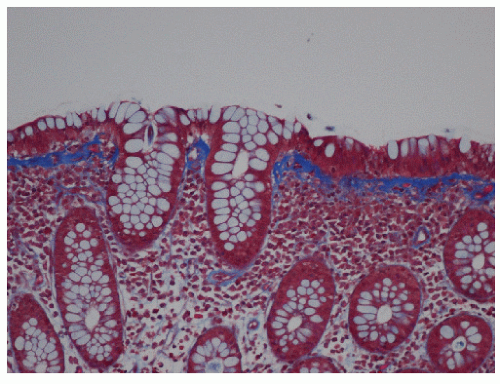

The clinical course of this disease is benign, with spontaneous remission of symptoms occurring within a few years of onset. Watery diarrhea may persist over weekly or monthly intervals in association with fecal incontinence. Anemia, increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate, hypokalemia, and hypoalbuminemia are common findings. Microscopic colitis is often misdiagnosed as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). However, its incidence in older individuals as well as the absence of abdominal discomfort as a significant complaint are distinguishing features.274 Endoscopic examination and radiologic studies have demonstrated a normal appearing mucosa in the majority of individuals. However, edema, friability, pinpoint mucosal hemorrhages, and hyperemia have been occasionally seen.248 Definitive diagnosis is based on histologic evaluation of colonic biopsies. Although microscopic colitis is a diffuse disease, it is recommended that one avoid rectal biopsies because the subepithelial collagen layer tends to be thicker in the rectum.274 Both subtypes demonstrate damage to the epithelial cells, such as flattening and depletion along with a predominantly mononuclear inflammation of the lamina propria and preservation of crypt architecture. The inflammation is found to be remarkably uniform, indicative of a total colitis. As mentioned, additional histologic features distinguish lymphocytic colitis from collagenous colitis. Lymphocytic colitis is characterized by greater than 20 intraepithelial lymphocytes per 100 surface epithelial cells (Figure 33-2), whereas a thickened subepithelial collagen layer is typical in collagenous colitis (Figure 33-3).89 The thickening of the subepithelial collagen layer may be a response to chronic inflammation or a local abnormality of collagen synthesis.289 It has been postulated that the disease may be attributable to reduced cell turnover, allowing fibrocytes to remain longer in the mature phase, hence producing more collagen and a thicker collagen plate.158 Another subtype, although rare, has been described by Sandmeier and Bouzourene.271 This type is characterized by the presence of subepithelial multinucleated giant cells, which the authors consider an important diagnostic criterion in the differential diagnosis of granulomatous infections and Crohn’s disease. Moreover, it seems that this atypical subtype of microscopic colitis has a more favorable prognosis and a better response to corticosteroid therapy.

Recommended treatments have included nonspecific antidiarrheal agents, such as loperamide, bismuth subsalicylate, sulfasalazine, mesalamine, bile acid-binding agents (e.g., cholestyramine), budesonide, prednisone, and in refractory cases, immunosuppressive drugs.118,274 In the Swedish experience, prednisolone was most effective, with a response rate of 82%. However, the required dose was often quite high, and the effect was not maintained following withdrawal of the medication. The response rates for antibiotics, cholestyramine, and loperamide were 63%, 59%, and 71%, respectively. Conversely, spontaneous resolution may occur.32 Reported success rates with sulfasalazine and mesalamine are lower (40% to 50%).274 A publication by the Cochrane database concerned a review of five randomized trials. It identified three treatment options for collagenous colitis. Budesonide was found to be an effective agent for the management of this disease; however, there was weak evidence to support the value of bismuth subsalicylate and prednisolone.58 More recently, several randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trials have demonstrated the efficacy of oral budesonide in both subtypes of microscopic colitis. Two trials involved the administration of budesonide, 6 mg daily, as maintenance treatment over 6 months in patients with collagenous colitis. The response rates in the treatment groups as compared with the placebo groups were 74.0% and 76.5% compared to 35% and 12%, respectively.33,201 A third trial reported a response rate of 86% versus 48% placebo in patients with lymphocytic colitis who were given budesonide, 9 mg daily, for a 6-week duration.

Clinical relapses were noted but were treatable with repeated administration of budesonide.202

Clinical relapses were noted but were treatable with repeated administration of budesonide.202

Neutropenic Enterocolitis (Ileocecal Syndrome or Typhlitis)

Neutropenic enterocolitis also known as ileocecal syndrome or typhlitis is a syndrome associated with bowel wall necrosis that was initially recognized in pediatric leukemic patients.69 With the development of effective chemotherapeutic agents, this clinical entity has become increasingly prevalent in the adult population. It can occur during treatment of hematologic malignancies, especially leukemia, lymphoma, and aplastic anemia.172 Those chemotherapeutic agents associated with neutropenic enterocolitis include paclitaxel, gemcitabine, cytosine, arabinoside, vincristine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, and daunorubicin.69 Neutropenic enterocolitis has also been reported as a complication of other therapeutic modalities, such as antithyroid therapy,60 and chemotherapy for lung, breast, ovarian, and colon cancer,69,101 or as the presenting complication of acute lymphoblastic leukemia.244 It has also been described as a complication of cyclic neutropenia, a rare benign hematologic disorder.222 Profound neutropenia secondary to chemotherapy has been considered the hallmark of the disease and the major etiologic factor in its development.213 This is a condition characterized by regular oscillations in blood neutrophil counts, in which sporadic disappearance of these cells from the circulation occurs. Involvement of the process is most commonly seen in the cecum, possibly due to its distensibility and limited blood supply.85 Other frequent sites include the terminal ileum and right colon, possibly because of the higher concentration of lymphatic tissue in these areas.

Patients exhibit symptoms of diarrhea, abdominal pain, sepsis, and findings typical of acute appendicitis. Even when the pain is localized to the right lower quadrant, the rapidity of the appearance of toxicity, with tachycardia, fever, and delirium, can be extremely dramatic. Koea and Shaw reported three individuals with leukemia who presented with fever, abdominal pain, and signs of peritonitis localized to the right iliac fossa.166 Each patient was found to have a nonviable cecum.

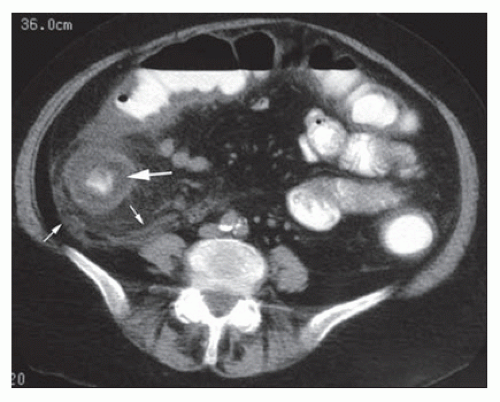

The pathogenesis of the disease involves disruption of the intestinal mucosa in a neutropenic state compounded by damage secondary to chemotherapy. The disruption of gut mucosal integrity allows for the invasion of pathogenic bacteria leading to the release of endotoxins and to the development of necrosis and hemorrhage (Figure 33-4). A wide spectrum of bacteria have been identified in surgical specimens, such as clostridial species, gram-negative rods, gram-positive cocci, and Candida species.69 The diagnosis is based on clinical presentation and a low neutrophil count. The presence of radiologic abnormalities, however, is essential with CT and ultrasound imaging serving as the studies of choice (Figure 33-5).85 Kirkpatrick and Greenberg described pneumatosis intestinalis as the most common computed tomographic observation suggestive of neutropenic enterocolitis (21% of patients).160 Bowel wall thickening, mesenteric stranding, bowel dilatation, mucosal enhancing, and ascites are also frequently reported.160 In patients who are hemodynamically unstable, ultrasound should be considered as an alternative diagnostic modality given its ease of use and ability to quickly detect bowel wall thickening as well as rapidly eliminating other possible diagnoses, such as appendicitis and pancreatitis.69 One prospective study evaluating the use of ultrasound in leukemic patients postchemotherapy found that bowel wall thickening greater than

4 mm was present only in those who symptomatically satisfied the criteria for neutropenic enterocolitis. As such, some advocate that the diagnostic criteria for neutropenic enterocolitis should include the presence of bowel wall thickening identified on CT scan or ultrasound (greater than 4 mm on transverse scan over greater than 30 mm on longitudinal scan), in addition to the clinical presentation of fever and abdominal pain.85

4 mm was present only in those who symptomatically satisfied the criteria for neutropenic enterocolitis. As such, some advocate that the diagnostic criteria for neutropenic enterocolitis should include the presence of bowel wall thickening identified on CT scan or ultrasound (greater than 4 mm on transverse scan over greater than 30 mm on longitudinal scan), in addition to the clinical presentation of fever and abdominal pain.85

FIGURE 33-4. Neutropenic enterocolitis (typhlitis). Crypts of this mucosal fold are intensely inflamed and necrotic in an individual on chemotherapy. (Original magnification × 380.) |

Given high mortality rates, the management of neutropenic enterocolitis has been traditionally aggressive, with a low threshold for surgical intervention. However, because an increasing number of cases successfully treated with medical therapy alone have been reported, there has been a shift in the treatment paradigm. Intensive support with close monitoring, fluid resuscitation, bowel rest, and broad-spectrum antibiotics are key components to conservative management. Antibiotic treatment may be initiated with single drug regimens, such as piperacillin-tazobactam, or with dual agents, such as a beta-lactam antipseudomonal drug paired with an aminoglycoside. Coverage should be targeted at grampositive and gram-negative bacteria, as well as pseudomonas, clostridial, and fungal species. Moreover, the use of recombinant granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) has been administered to help normalize white blood cell levels and consequently to lead to clinical improvement. Its efficacy, however, is not well established and is currently recommended for only the sickest of patients.69

Surgical intervention should be considered in those individuals with persistent gastrointestinal bleeding, free intraabdominal perforation, clinical worsening, or to exclude other acute abdominal disease processes. Resection is necessary with perforated or necrotic bowel; however, in the setting of neutropenia, a primary bowel anastomosis is not recommended. Rather, resection with diversion is the preferred alternative.85

Diversion Colitis, Disuse Colitis, and Starvation Colitis

Diverting the fecal stream and defunctionalizing the bowel can produce a noninfectious colitis, an observation made by Glotzer and colleagues in 1981.113 Generally, patients are asymptomatic, although mucus discharge and bleeding may be noted. Fenton and Siegel have shown that 70% of their ostomy patients had gross or microscopic findings of diversion colitis despite the absence of symptoms.100 Roe and colleagues reported that all of their 12 patients who had undergone a Hartmann’s procedure demonstrated histologic abnormalities consistent with diversion colitis by 3 months.253 An association of microcarcinoids with diversion colitis has also been reported.122 This occurrence has been attributed to neurogenic hyperplasia, which represents proliferation of a separate, neuron-associated, extraglandular population of endocrine cells.120

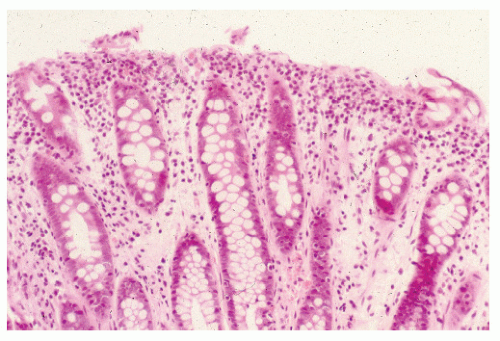

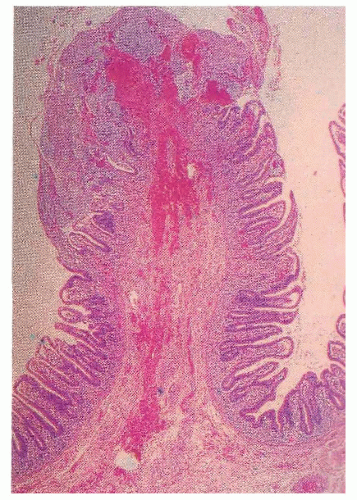

Proctosigmoidoscopic findings are essentially that of a mild inflammatory bowel disease suggestive of ulcerative colitis. Microscopic alterations, however, tend to be rather focal and include crypt abscesses, epithelial cell degeneration, acute and chronic inflammation in the lamina propria, and regenerative changes in the crypts (Figure 33-6).113 The crypt cell production rate has been determined to be less than half that of controls. Additionally, crypt length and width are lower.10 However, the histologic picture with the condition is quite variable. Pathologic evaluation of more severely diseased, resected specimens may demonstrate diffuse nodularity caused by lymphoid hyperplasia and an inflammatory process confined to the mucosa and submucosa.214

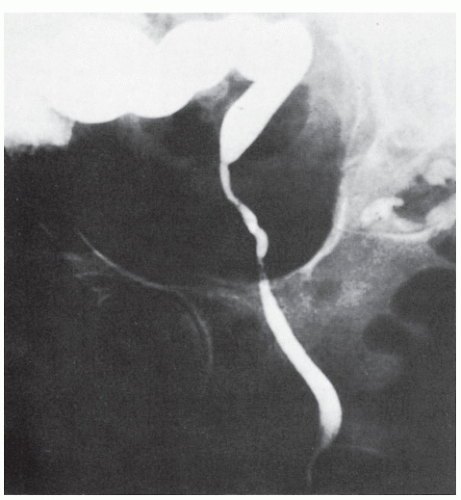

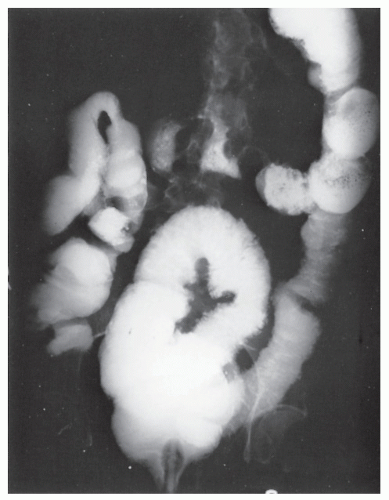

The mucosa of the intestinal tract is unique in that it draws nutrients not only from the vasculature, but also from the bowel lumen.254 It is not difficult to appreciate how this entity can develop when examining the radiologic picture shown in Figure 33-7. Nutrition of the colonic epithelial cells is mainly from short-chain fatty acids produced by bacterial fermentation in the colonic lumen.254 Deficiency in these substances initially leads to mucosal hypoplasia and subsequently to a more typical picture of nonspecific inflammatory bowel

disease. Harig and colleagues have shown that negligible amounts of short-chain fatty acids can be identified in a segment of excluded rectosigmoid.129 They further demonstrated that installation of a solution containing short-chain fatty acids twice daily resulted in the disappearance of symptoms and in the inflammatory changes observed at endoscopy within a period of 6 weeks. Short-chain fatty acids have also been used for the management of diversion colitis in children.156 Others have shown that the condition may be successfully treated with the use of 5-aminosalicylic acid enemas.307 However, the only curative approach is stoma reversal or rectal excision.

disease. Harig and colleagues have shown that negligible amounts of short-chain fatty acids can be identified in a segment of excluded rectosigmoid.129 They further demonstrated that installation of a solution containing short-chain fatty acids twice daily resulted in the disappearance of symptoms and in the inflammatory changes observed at endoscopy within a period of 6 weeks. Short-chain fatty acids have also been used for the management of diversion colitis in children.156 Others have shown that the condition may be successfully treated with the use of 5-aminosalicylic acid enemas.307 However, the only curative approach is stoma reversal or rectal excision.

FIGURE 33-7. Barium study reveals an atrophic rectum, a consequence of disuse for many years following the creation of a colostomy. |

The affected bowel rapidly returns to a normal appearance following reestablishment of intestinal continuity. Orsay prospectively evaluated 34 patients who were scheduled to undergo colostomy closure and who were demonstrated to have diversion colitis.225 There was no increased infection rate or any other complications following colostomy closure.

Iatrogenic Chemical Colitis (Pseudolipomatosis)

Chemical colitis is a rare clinical entity that can be induced by iatrogenic means with contaminated endoscopes or with intentional or accidental administration of corrosive enemas. Iatrogenic chemical colitis was first described in the 1960s and has been reported in the literature in numerous case reports and series.281 Although disinfectant solutions are known to be caustic to the intestinal mucosa, controversy exists as to the exact causative agent. The main disinfectants implicated are glutaraldehyde, peracetic acid, and hydrogen peroxide (a breakdown product of peracetic acid when it is combined with water). The residual presence of such chemicals on endoscopic equipment may be the result of malfunction of automated disinfecting devices or lack of staff education in proper cleansing techniques.

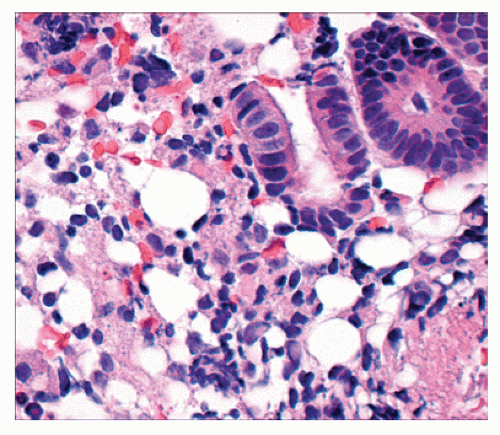

Injury to the colon typically becomes manifest at the time of endoscopy with the classic “snow white sign,” multiple areas of elevated whitish yellow plaques of variable size and confluence. Histologically, such lesions are characterized by empty vacuoles within the submucosa; hence, the term pseudolipomatosis (Figure 33-8).145,210

FIGURE 33-8. Iatrogenic chemical colitis (pseudolipomatosis). Colonic mucosa demonstrating spaces devoid of epithelial lining in the lamina propria. Note the similarity to pneumatosis coli (see Figure 26-106). Note also the absence of nuclei. These are empty spaces, not lipocytes. (Original magnification × 560.) |

Signs and symptoms range from no clinical sequelae to fever, abdominal pain, and bloody diarrhea within 48 hours of endoscopic examination. Radiologic findings on CT scan after glutaraldehyde-induced colitis may demonstrate a “target sign” of circumferential colonic wall thickening. Resolution is usually seen with bowel rest and conservative treatment. Empiric antibiotics and steroids may be administered, but no evidence of their efficacy has been reported.281

Corrosive Colitis

Oral administration of a host of corrosives is a well-recognized entity for which surgical intervention is often required. Less well recognized, however, is the installation of various toxic or corrosive materials by means of an enema. Cappell and Simon reviewed the literature on the reported intra-rectally administered toxic agents and found that the most common was hydrogen peroxide.45 Other agents included detergent enemas, herbal medicines, acetic acid, ethyl alcohol, sodium hydroxide, and hydrofluoric acid. Pikarsky and colleagues presented a case of severe formalin-induced colitis 5 days after rectal instillation of formalin for radiation proctitis.238 Drugs such as ergotamine can also be associated with inflammatory reaction and toxicity. Toxic exposure may result from conventional medical therapy, unconventional medical therapy, radiographic examination, colonoscopic examination (see previous discussion), deliberate self-mutilation, or accidental self-administration.45

Rectal bleeding, diarrhea, and abdominal pain are frequent symptoms. Endoscopic examination usually reveals nonspecific changes consistent with inflammatory bowel disease, including erythema, ulceration, granularity, friability, and purulent exudate. A history of medication use or exposure to toxic agents is obviously helpful.

Treatment is generally supportive care, although emergency laparotomy and bowel resection may be required for fulminant acute colitis, stricture, or perforation (see also Chapter 17).

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drug Colopathy

Adverse effects of NSAIDs on the upper gastrointestinal tract and small intestine are well recognized.84 Since the initial description of NSAID-induced colonic injury by Debenham,86 a growing number of reports have associated the use of NSAIDs and salicylates with colonic complications. However, the true incidence of NSAID colopathy is unknown. A study from Jersey (United Kingdom) estimated that approximately 1:1,200 NSAID users may develop colitis.112 Recognized colonic complications secondary to NSAID use include the development of primary macroscopic colitis, worsening of inflammatory bowel disease, collagenous colitis, gastrointestinal bleeding, and increased complications in association with diverticular disease.16

The clinical presentation of NSAID-induced colitis is based on the development of an acute, nonspecific inflammatory process involving the colonic mucosa.94 With long-term NSAID use, it may progress to chronic disease characterized by the presence of fibrosis and strictures.2 Symptoms include bloody diarrhea, sporadic melanotic stool leading to irondeficiency anemia, weight loss, fatigue, anorexia, and even death. The pathogenesis of NSAID-induced colitis may be related to the inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis.84

In addition to the oral route, NSAID-induced suppository toxicity has been recognized.

In addition to the oral route, NSAID-induced suppository toxicity has been recognized.

Colonoscopy may demonstrate diffuse inflammation, with erosions or ulcerations. The presence of diaphragmatic-like strictures or webs, most commonly in the right colon, has been described as a pathognomonic sign of NSAID-induced colitis.149 However, the most common finding is a solitary or limited number of cecal ulcerations, or they may be scattered throughout the colon and rectum.241 The condition may be difficult to differentiate from that of ulcerative colitis in its early presentation.

NSAID ingestion should certainly be considered in the differential diagnosis of colitis. The use of NSAIDs in the form of suppositories may induce rectal bleeding and proctitis due to the high concentration of the drug in direct contact with the rectal mucosa.111,180 Moreover, the severity of rectal symptoms may be dose dependent. It has been estimated that up to 30% of patients using NSAID-containing suppositories may develop rectal symptoms such as pain, inflammation, bleeding, ulcerations, and stricture.84

One would certainly expect an ameliorative response of the bowel to the discontinuation of the medication. Additionally, the use of sulfasalazine and metronidazole has proven to be somewhat beneficial.95 Surgical treatment is reserved for cases of life-threatening complications or refractory colitis.

Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

Toxic epidermal necrolysis is a rare and severe reaction to certain drugs that results in full-thickness epidermal skin necrosis.48 Other mucosal surfaces have been implicated, including the large bowel. The most common drugs associated with this condition include sulfonamides, penicillin, NSAIDs (see previous discussion), phenytoin anticonvulsants, and barbiturates.48

Symptoms include abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea, usually concomitant with the development of the skin lesions. Several cases of colonic necrosis complicating this condition have been reported.48

▶ INFECTIOUS COLITIDES

Tis now the very witching time of night, when churchyards yawn and hell itself breathes out contagion to this world.

—WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE: Hamlet, III, 2

The gastrointestinal tract is susceptible to infection by a host of organisms, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. The upper intestine tends to be attacked by organisms that produce toxins (e.g., Vibrio cholerae), whereas in general, colonic infection is associated with organisms that produce dysentery (e.g., Shigella). In the former situation, infection tends to leave the mucosa uninvolved, whereas in the latter, the intestinal mucosa is often ulcerated or destroyed. Upper intestinal organisms tend to produce diarrhea with severe dehydration. However, there is usually no septicemia. Those that affect the large bowel often produce severe abdominal pain, tenesmus, and signs and symptoms of generalized infection (e.g., malaise, pyrexia). A rapid onset is often due to the presence of a toxin produced by a bacterium rather than to the bacterium itself. This type of syndrome is occasionally associated with certain restaurant foods. Gorbach stated that the incubation period from a toxin is so brief that the symptoms occur either when one is paying the check or when on the way to the parking lot.119

Most episodic diarrheas are caused by an infection acquired by ingesting fecally contaminated food or beverages. Escherichia coli is the most common pathogen, although many other bacteria, viruses, and protozoa have been implicated.74 The “immunologically naive” traveler to developing areas is the individual most susceptible to the bacterial and protozoal indigenous organisms.124 Prevention can be best described by the adage, “cook it, boil it, peel it, or forget it.”124

Traveler’s Diarrhea Prophylaxis

The main nonantibiotic agent for prophylaxis against traveler’s diarrhea is bismuth subsalicylate, which has been shown to decrease incidence rates from 40% to 14%. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend avoidance of prophylactic antibiotics for the average traveler due to concerns for possible adverse drug reactions. For those who are immunosuppressed or at high risk, prophylaxis with fluoroquinolones is the current recommendation. Although the majority of diarrheal illnesses represent little more than a self-limited nuisance, oral rehydration along with antibiotic treatment is recommended for severe cases. Fluoroquinolones such as levofloxacin are considered first-line therapy with azithromycin as an alternative in cases of drug resistance.75

Comprehensive microbiologic testing and thorough gastrointestinal studies for every individual with the complaint of diarrhea are both impractical and costly.130,329 As enteric infections frequently present with vague, nonspecific signs and symptoms, it is imperative that the clinician obtain a thorough history considering recent travel and other possible sources of exposure to infectious agents. Generally, for the younger patient, no investigations, except perhaps a rigid or flexible sigmoidoscopy and biopsy, are necessary if weight is stable and the stool is free of occult blood.130 Nonetheless, a few individuals will require a more extensive evaluation, a decision that must rest with the physician’s clinical judgment.

In this section, the various enteric infections of potential interest to the surgeon are discussed with respect to epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, therapy, and prevention.

▶ BACTERIAL INFECTIONS

Clostridium difficile Colitis, Pseudomembranous Colitis, and Antibiotic-Associated Colitis

The first reported case of pseudomembranous colitis actually antedated the antibiotic era and is generally attributed to Finney of Johns Hopkins.102 His patient developed bloody diarrhea, perhaps as a consequence of enema feedings following a gastric procedure. The discussants of his paper presented what were than a “who’s who” of American medicine prior to the turn of the 20th century—Halsted, Osler, Thayer, and Flexner.

Epidemiology, Etiology, and Incidence

Clostridium difficile is a gram-positive, anaerobic, sporeforming bacillus, first described in 1935 as a component

of normal newborn fecal flora.127 However, the role of C. difficile in the pathogenesis of antibiotic-associated colitis was not reported until the late 1970s.295 The rising incidence of C. difficile colitis in hospitalized patients has become a matter of concern among physicians, especially surgeons. Recent reports have shown that 20% to 25% of hospitalized individuals will acquire C. difficile. Moreover, one-third of these patients will develop diarrhea.123 In a prospective analysis from the Department of Surgery at the New York Hospital-Cornell University Medical Center, the incidence of diarrhea in surgery patients was 6.1%, and the incidence of C. difficile-associated diarrhea was found to be 2%.192 C. difficile colitis is now the most frequent cause of nosocomial infectious diarrhea, with an estimated half a million cases annually in nursing homes and hospitals in the United States.265 Generally, this has been attributed to a heightened awareness of the condition, better diagnostic methods, more widespread use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, and the increasing number of elderly or immunocompromised patients.36,184,192 During the past 10 years, researchers have identified highly virulent strains of C. difficile, NAP1/BI/027 and PCR ribotype 078, which have caused severe disease in the United States and in Europe.221

of normal newborn fecal flora.127 However, the role of C. difficile in the pathogenesis of antibiotic-associated colitis was not reported until the late 1970s.295 The rising incidence of C. difficile colitis in hospitalized patients has become a matter of concern among physicians, especially surgeons. Recent reports have shown that 20% to 25% of hospitalized individuals will acquire C. difficile. Moreover, one-third of these patients will develop diarrhea.123 In a prospective analysis from the Department of Surgery at the New York Hospital-Cornell University Medical Center, the incidence of diarrhea in surgery patients was 6.1%, and the incidence of C. difficile-associated diarrhea was found to be 2%.192 C. difficile colitis is now the most frequent cause of nosocomial infectious diarrhea, with an estimated half a million cases annually in nursing homes and hospitals in the United States.265 Generally, this has been attributed to a heightened awareness of the condition, better diagnostic methods, more widespread use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, and the increasing number of elderly or immunocompromised patients.36,184,192 During the past 10 years, researchers have identified highly virulent strains of C. difficile, NAP1/BI/027 and PCR ribotype 078, which have caused severe disease in the United States and in Europe.221

JOHN MILLER TURPIN FINNEY (1863-1942)

|

Finney was born in Natchez, Mississippi, the son and grandson of Presbyterian ministers. He was raised in Bel Air, Maryland, where his father assumed a church position. Finney attended Princeton University, receiving his bachelor’s degree in 1884, and completed his medical education at Harvard Medical School in 1889. Following his graduation, he interned at the Massachusetts General Hospital before being appointed to a faculty position at the Johns Hopkins Medical School where he remained of his entire career. He was well respected within the Baltimore community as a distinguished citizen and surgeon. He served as head of the surgical dispensary and ultimately held the position of professor of clinical surgery and surgeon-in-chief. Finney was highly sought after and asked to assume the presidency of Princeton University and chairman of the Department of Surgery at Harvard, both of which he declined. Devoted to surgery, Finney developed one of the largest practices in the United States while playing a pivotal role in establishing the Johns Hopkins’ Surgical Residency Training Program. When the American College of Surgeons was formed in 1913, Finney was named its first president. He also went on to serve as president of the American Surgical Association. During World War I, Finney was recruited as director of a base hospital in France. He ultimately became chief consultant in surgery to the U.S. Army and was ultimately awarded the Distinguished Service Medal and the French Legion of Honor. Although he retired in 1933, Finney remained active on various academic boards, devoting much of his time to charitable work as chairman of the Baltimore Chapter of the American Red Cross. (Photo courtesy of the Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, MD.)

Any patient who develops diarrhea either during or after receiving antibiotic therapy must be considered at risk for this complication until proven otherwise, although it is certainly possible that colitis may not be associated with antibiotic therapy.90 Antibiotic-associated diarrhea is often mild and self-limited, demonstrating rapid improvement with discontinuance or change of the antibiotic. Although almost one-third of cases of antibiotic-associated diarrhea are due to C. difficile, 2% to 3% are secondary to other infectious organisms, such as Clostridium perfringens, Staphylococcus aureus, and Candida albicans.136 C. difficile-associated diarrhea may commence within 48 hours after the administration of the drug. However, the condition can develop after 6 to 10 weeks following stoppage of the antibiotic, an observation noted in 25% to 40% of patients.123

The pathophysiology of C. difficile colitis is related to the breakdown of normal colonic microflora, followed by colonization with C. difficile and the production of invasive toxins leading to mucosal inflammation. Contamination occurs via the oral-fecal route. C. difficile produces two toxins in the intestinal lumen, known as A (enterotoxin) and B (cytotoxin), which adhere to the surface of the epithelial layer and produce an inflammatory reaction. Toxin A causes actin disaggregation and intracellular release of calcium. Toxin B is a necrotizing enterotoxin, significantly more potent than toxin A. Both toxins, however, cause colonic mucosal damage and diarrhea. Nonetheless, C. difficile rarely produces colonic injury by direct invasion of the mucosa.97 The severity of comorbid conditions and low serum levels of IgG antibody to toxin A have been related to a higher probability of acquiring symptomatic C. difficile colitis.173

Relatively rare in comparison to hospital rates, the reported incidence of community-associated C. difficile infection ranges from 6.9 to 46 cases per 100,000 person-years in the United States.221 Two to three percent of healthy individuals are asymptomatic carriers. However, more than 80% of neonates and up to 70% of infants and young children harbor C. difficile in fecal flora without any intestinal manifestations.123,126 It has been noted in recent years that the incidence of infection in populations previously considered low risk, such as children and pregnant women, has increased. Contaminated food, soil, and water have been considered as potential sources for community infection. However, no conclusive evidence has been demonstrated as of yet.265

The most common antibiotics associated with C. difficile colitis are cephalosporin, clindamycin, ampicillin, and amoxicillin. However, virtually all antibiotics, including metronidazole and even vancomycin (perhaps doubtful), have been suggested to cause this syndrome. In the Mayo Clinic experience, 70% of their cases were associated with a cephalosporin.297 The significance of this observation is somewhat diminished by the fact that this is the class of antibiotics most often administered in hospitals.261 In addition to antibiotics, C. difficile colitis has also been reported in patients receiving antineoplastic agents, such as cisplatin, doxorubicin, methotrexate, teicoplanin,

and tacrolimus.215 The condition has also been reported as a complication of sulfasalazine therapy in a patient with inflammatory bowel disease.239 The occurrence of this particular complication poses a considerable challenge in the differential diagnosis because the symptoms of the two diseases are very similar.

and tacrolimus.215 The condition has also been reported as a complication of sulfasalazine therapy in a patient with inflammatory bowel disease.239 The occurrence of this particular complication poses a considerable challenge in the differential diagnosis because the symptoms of the two diseases are very similar.

TABLE 33-1 Practice Guidelines for Prevention and Control of Clostridium difficile Infection (CDI) | |

|---|---|

|

Those who appear to be at increased risk are individuals who are somewhat immunocompromised (e.g., with cystic fibrosis, neurologic disease, liver or renal disease, malnutrition, diabetes mellitus, hematologic disorders).261,286 Other factors associated with an increased risk of infection include advanced age, malignancy, chronic pulmonary disease, prolonged hospitalization (more than 4 weeks), nursing home residents, transfer from another hospital, antibiotic course of more than 7 days, treatment with more than one antibiotic, immunosuppressive medication, chemotherapy, antiperistaltic medications, antacid therapy, an intensive care unit location, non-single-room accommodation, and those conditions in which the intestinal motility is altered.36 With respect to pathogenesis and prevention, a number of authors have emphasized that education of the hospital staff is mandatory if one is to reduce the incidence of this common and costly colitis.167 For example, McFarland and colleagues found that the infection is frequently transmitted among hospitalized patients and that the organism is often present on the hands of hospital personnel caring for these individuals.194 The Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) have published updated clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and control of C. difficile infection (Table 33-1).70

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical presentation of C. difficile colitis varies from the asymptomatic carrier to a fulminant illness that may result in death. Approximately 20,000 people die annually in the United States from C. difficile infection.265 Mild disease presents with diarrhea, crampy abdominal pain, and diffuse patchy, nonspecific colitis on endoscopic examination. Moderate cases are often associated with fever, nausea, anorexia, abdominal distention, and cramps, in addition to profuse diarrhea. Those patients with severe C. difficile colitis appear toxic, dehydrated, and with signs of peritonitis on physical examination. These individuals in particular may go on to manifest a fulminant colitis, develop a colonic perforation, and succumb to the complications of their disease.

Evaluation

The initial assessment of a patient with possible C. difficile- associated diarrhea and colitis includes a complete history and physical examination as well as laboratory evaluation of electrolytes, white blood cell count, nutritional status, and stool testing to rule out other sources of diarrhea. Dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, leukocytosis, and hypoalbuminemia may often accompany severe disease. Stool examination reveals the presence of leukocytes in one-half of the cases. The hemoccult test may be positive in severe colitis, but grossly bloody diarrhea is unusual.

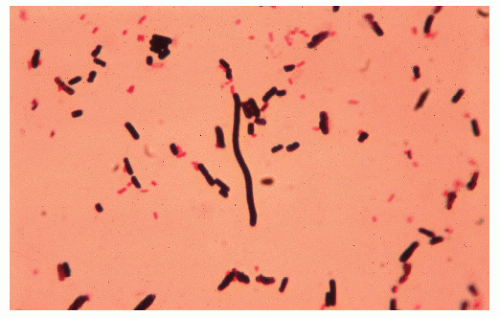

The most sensitive test for diagnosing C. difficile infection is stool culture (Figure 33-9). Despite a long turnaround time, stool culture in combination with toxigenic culture is the current diagnostic standard. With a lack of a single test with adequate sensitivity and specificity, the development of two- or three-step testing has emerged. The SHEA-IDSA clinical practice guidelines recommend the initial use of an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) of glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) followed by either cell cytoxicity assay or toxigenic culture of GDH-positive stool as confirmation. Another alternative that may prove to be sensitive and specific with a rapid testing time is the PCR assay. Several PCR-based assays are currently available. However, further investigation is necessary to promote its routine use.70

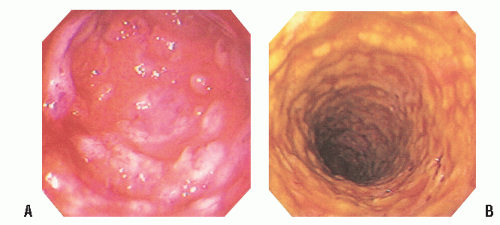

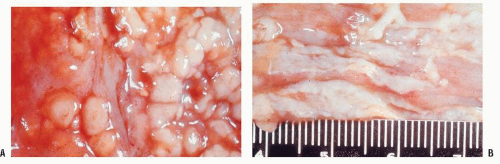

Endoscopic evaluation will demonstrate edema and mucosal inflammation. Pseudomembranes are present in 14% to 25% of patients with mild disease and 87% of those with severe colitis.122 The disease often involves the entire colon. Therefore, colonoscopy is preferable to that of flexible sigmoidoscopy because 10% of patients present with pseudomembranes beyond the reach of the sigmoidoscope (Figure 33-10). Seppälä and associates also stressed the importance of colonoscopy in the diagnosis of this condition.280 In a review of 16 patients with histologically proven antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis, only 31% were confirmed by sigmoidoscopy, as compared with 85% in whom colonoscopy was performed. Others have noted

the importance of total colonoscopy as the preferred means for establishing the diagnosis, particularly because there is not uncommonly right-sided involvement and a relatively normal distal bowel.40,82,266,270,301 Tedesco showed that five of six patients with tissue culture evidence of a clostridial toxin in the stool had either a normal or merely an edematous distal rectal mucosa.301 Thus, proctosigmoidoscopy would have failed to identify the abnormality.

the importance of total colonoscopy as the preferred means for establishing the diagnosis, particularly because there is not uncommonly right-sided involvement and a relatively normal distal bowel.40,82,266,270,301 Tedesco showed that five of six patients with tissue culture evidence of a clostridial toxin in the stool had either a normal or merely an edematous distal rectal mucosa.301 Thus, proctosigmoidoscopy would have failed to identify the abnormality.

FIGURE 33-9. Clostridium difficile. Gram stain of stool reveals gram-positive rods. (Original magnification × 800.) |

FIGURE 33-10. A,B: Colonoscopy clearly demonstrates the patterns of yellow and yellow-white adherent plaques in pseudomembranous colitis. |

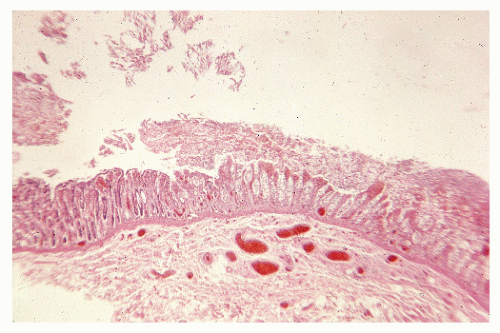

Biopsy of the lesion is not mandatory for confirming the diagnosis. However, if there is any question as to the etiology of the inflammatory change, tissue should be obtained (Figures 33-11 and 33-12). Histopathologic examination of the pseudomembranous plaque shows a mix of mucinous fibrinous exudate and polymorphonuclear neutrophils.

Radiographic imaging studies may reveal a paralytic ileus and pancolonic dilatation. Differential diagnosis must include Ogilvie’s syndrome (colonic ileus), ischemia, and volvulus.305 Pneumoperitoneum due to colonic perforation in severe or toxic colitis can also be found on plain abdominal radiography. Computerized tomography may show a diffusely thickened and edematous colonic wall.215 Barium enema examination may demonstrate “thumbprinting,” which is due to bowel wall edema. In more advanced stages, severe ulceration may be present (Figure 33-13). The procedure, however, is contraindicated in the acutely ill patient because of the risk of precipitating toxic megacolon or a perforation.72,286

FIGURE 33-11. Pseudomembranous colitis. Superficial necrosis with acute inflammatory mucosal exudate. (Original magnification × 80.) |

Treatment

Despite the high mortality rate in critically ill individuals, most patients with mild C. difficile colitis will recover even without specific treatment. Adequate antibiotic therapy with metronidazole or vancomycin leads to symptomatic improvement in the overwhelming majority within the first 24 to 72 hours, with complete resolution in 1 or 2 weeks.

Treatment of C. difficile colitis includes cessation of the causative antibiotic. Adequate fluid and electrolyte replacement is also essential to overall patient management. Asymptomatic carriers do not require treatment. Conversely, fulminant colitis frequently requires intensive care monitoring and emergency surgery. More than 95% of patients respond to therapy with oral or intravenous metronidazole or oral vancomycin.123,215 Metronidazole is the treatment of choice for mild-to-moderate disease, leading to a 99.9% reduction in organisms. It provides a 95% to 100% response rate and is more cost effective than vancomycin.123 The recommended dose is 500 mg orally three times daily, for a total of 10 to 14 days.70 The intravenous route is used in patients who are intolerant of oral intake.

Vancomycin is equally as effective as metronidazole when taken orally because the poor intestinal absorption promotes a high luminal concentration. Its mechanism of action is the inhibition of bacterial wall synthesis. In addition to the high cost, the major disadvantage of this drug is the emergence of vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Furthermore, unlike metronidazole,

intravenous vancomycin is not excreted into the gastrointestinal tract. Vancomycin is considered the treatment of choice for an initial episode of severe C. difficile infection.70 The recommended dose is 125 mg, orally, four times daily for 10 to 14 days and 40 mg/kg/day, divided three or four times a day for 7 to 10 days in pediatric patients.123 Vancomycin enemas can be used in patients with C. difficile proctosigmoiditis or in those who have undergone emergency subtotal colectomy with an end ileostomy. Under these circumstances, with a diseased rectum, topical vancomycin is a very good treatment option.

intravenous vancomycin is not excreted into the gastrointestinal tract. Vancomycin is considered the treatment of choice for an initial episode of severe C. difficile infection.70 The recommended dose is 125 mg, orally, four times daily for 10 to 14 days and 40 mg/kg/day, divided three or four times a day for 7 to 10 days in pediatric patients.123 Vancomycin enemas can be used in patients with C. difficile proctosigmoiditis or in those who have undergone emergency subtotal colectomy with an end ileostomy. Under these circumstances, with a diseased rectum, topical vancomycin is a very good treatment option.

FIGURE 33-12. Pseudomembranous colitis. Total necrosis of the mucosa with inflammatory exudate in the submucosa. (Original magnification × 80.) |

FIGURE 33-13. Pseudomembranous colitis. Barium enema demonstrates extensive ulceration. Note the collar button appearance of the ulcers extending into the bowel wall. |

Anion exchange resins such as cholestyramine (Questran) will bind to the C. difficile toxin, forming a nonabsorbable complex with bile acids in the intestinal lumen. Cholestyramine will also bind to vancomycin. Therefore, both medications should not be used in combination. This drug is less efficacious than metronidazole or vancomycin, but it may have a role in patients with relapsing disease. The suggested dose is 4 g orally, three times daily for 10 to 14 days.97,123 Because C. difficile is a transferable enteric pathogen, stool precautions for the duration of the illness are advised.17

FIGURE 33-14. Pseudomembranous colitis. Opened partial specimen from total colectomy demonstrates the classic mucosal findings of this disease. |

FIGURE 33-15. Pseudomembranous colitis. A,B: Whitish plaques of pseudomembranes cannot be wiped off. The patient expired of acute leukemia. |

Medications that slow peristalsis should be avoided because elimination of the toxin is inhibited.”99 In fact, some have suggested that reduced colonic motility as seen with colonic obstruction, sepsis, uremia, generalized debilitating conditions, burns, and other illnesses may contribute to the development of pseudomembranous colitis.66

Colectomy is generally performed in patients who develop megacolon, an acute abdomen, perforation, and septic shock. In patients who are severely ill, close monitoring of serum lactate levels as well as white blood cell counts may be useful in determining the need for surgical intervention. Significantly higher perioperative mortality is associated with a serum lactate level of 5 mmol/L or greater and a white blood cell count of 50,000 cells/µL.70 The most frequent indication for operative intervention is perforation, although pseudomembranous colitis may be a terminal complication in patients with a malignancy. Figures 33-14 and 33-15 demonstrate the appearance of the mucosa in such individuals. Acute abdominal signs and symptoms may, in fact, be the

initial presenting manifestations.305 Total colectomy with ileostomy, preserving the rectum, is the preferred treatment for a perforation or for fulminant disease.184,197,211,212,308 It must be remembered that at laparotomy, the external colonic appearance may be deceptively normal. This finding should not influence the surgical procedure—that is, total colectomy.184 With sepsis or a dilated bowel, and in the absence of necrosis or perforation, an ileostomy alone may be adequate surgical management. However, there are no meaningful statistics concerning the relative merits of this option.

initial presenting manifestations.305 Total colectomy with ileostomy, preserving the rectum, is the preferred treatment for a perforation or for fulminant disease.184,197,211,212,308 It must be remembered that at laparotomy, the external colonic appearance may be deceptively normal. This finding should not influence the surgical procedure—that is, total colectomy.184 With sepsis or a dilated bowel, and in the absence of necrosis or perforation, an ileostomy alone may be adequate surgical management. However, there are no meaningful statistics concerning the relative merits of this option.

Lipsett and colleagues reported an overall mortality rate in their series of 38%, with a 100% mortality in those who underwent partial colectomy and a 14% mortality for those who underwent subtotal colectomy.184 Others report a high mortality rate for this disease, especially if a less than subtotal colectomy is performed.197,212,308

Recurrence

One of the concerns with this disease is the possibility of relapse following treatment, a frequency that has been reported to be from 10% to 30%.123 This often occurs within 1 to 3 weeks following completed therapy and is likely due to the original C. difficile strain. However, a new strain may be found, especially if the patient remains in the same high-risk environment. The number of relapses increases exponentially after the second episode to greater than 65%.123 Walters and colleagues reported a relapse of antibiotic-associated colitis while the patient was maintained on vancomycin therapy.316 Eight of 15 individuals so treated demonstrated a clinical relapse after therapy was discontinued. These results suggest that stool evaluation should be performed during and after treatment to indicate whether the antibiotic therapy should be maintained or reinstituted or that alternative therapeutic approaches be considered.

Recurrence due to antibiotic resistance has yet to be proven, but it seems that persistent C. difficile spores in the colon may lead ultimately to clinical disease. It has also been proposed that the absence of Bacteroides species predisposes to recrudescence. Attempts have been made to identify risk factors for recurrence, including those with prior C. difficile infection, chronic renal failure, prolonged antibiotic therapy, patients with community-acquired C. difficile, significant leukocytosis, and particular strains of C. difficile.98,215

Management in this situation is quite challenging, with no uniform treatment having been accepted. The first relapse after successful treatment of C. difficile colitis may be treated with a repeat course of metronidazole or vancomycin for a total of 10 to 14 days.215 This regimen is effective in 95% of cases. However, a small number of patients will go on to develop multiple episodes of recurrence. Metronidazole is not recommended beyond the first recurrence, however, because of possible neurotoxicity. Vancomycin may be used for multiple recurrences in a prolonged tapering or pulse regimen.70 In a recent case series, a regimen of oral rifaximin, 400 mg, twice a day for 2 weeks immediately after a course of vancomycin led to a cure rate of 86% in patients with multiple recurrences.141 Saccharomyces boulardii, in combination with standard antibiotic therapy, is also an option for refractory disease, but this is not available in the United States and is yet to proven as an effective therapy.70,123,140

Another treatment alternative is fecal transplantation via colonoscopy. It has reportedly been effective in small studies, but the results of the first randomized controlled study comparing fecal transplantation with antibiotic therapy in patients with recurrent C. difficile infection are still pending.15,255,311 Other treatment modalities such as immunoglobulin therapy and the use of monoclonal antibodies directed against C. difficile toxins require further investigation. Research and development of C. difficile toxoid and DNA vaccines are currently ongoing as well.221

Campylobacter Enteritis

Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli are the leading causes of infectious enterocolitis worldwide. In fact, Campylobacter has become one of the major causes of infectious diarrhea in the United States, with a reported 13 laboratory-confirmed cases per 100,000 annually.53 Within the United States, it is noted to occur most commonly in children younger than the age of 4. Internationally, infection is typically sporadic in poor developing countries as well as in military personnel stationed abroad.159 The organism is a curved or “gull wing” microaerophilic, grampositive rod. Transmission occurs by way of the fecal-oral route through contaminated fruit and water or by direct contact with infected animals or persons.30 Epidemiologic studies have demonstrated an association with the handling and consumption of poultry and beef. The risk of contamination is higher with raw meats, especially at barbecues. This is believed to be due to the ready transfer of the bacteria to other foods and then to the mouth.42 This bacterium is also found in shellfish and dairy products and has also been diagnosed in hospitalized patients. Campylobacter is vulnerable to temperature extremes as well as to oxygen in atmospheric concentrations. In contrast to that of Salmonella, Campylobacter does not survive in pelleted meals, egg powder, and spices.

Symptoms and findings may be difficult to differentiate from those of other diseases affecting the intestinal tract, particularly nonspecific inflammatory bowel disease.246 In fact, Campylobacter enteritis must be considered in the differential diagnosis of any patient who presents with rectal bleeding and diarrhea. Abdominal pain, fever, nausea, and vomiting may also be associated complaints. Toxic megacolon, necessitating total colectomy, has been reported.9

Proctosigmoidoscopic examination usually reveals an edematous, inflamed mucosa. Histologic examination of biopsy specimens is nonspecific. A double-contrast barium enema may demonstrate aphthoid ulcers and a stippled appearance.304

A high index of suspicion must be maintained if one is to establish the diagnosis and to initiate therapy promptly. Examination of the fecal specimen within 2 hours of passage by dark-field or phase-contrast microscopy may identify the organism.30 The presence of polymorphonuclear leukocytes in the fecal stream is not uncommon but is not pathognomonic for the condition.

Infection with C. jejuni may lead to various postinfectious sequelae, including reactive arthritis, Reiter’s syndrome, Guillain-Barré syndrome, IBS, and IBD.23 The incidence of IBS- and IBD-associated cases ranges from 4% to 32%. Research has demonstrated a consistent association between length of clinical illness (greater than 1 week) and the development of postinfectious IBS. Debate still remains, however, over the mechanism of disease as well as the question of whether infection with Campylobacter leads to IBS and IBD or whether patients with such intestinal diseases are simply predisposed to the bacterial infection.159

In the majority of patients, symptomatic infection is usually self-limited and does not require antibiotic therapy, but relapses are frequent. In severe cases, those associated with fever, bloody diarrhea, and cramping, hospitalization and fluid and electrolyte replacement may be necessary. Although the mainstay of treatment has been fluoroquinolones, antibiotic resistance has increased rapidly with a reported prevalence of 26% in 2007. Consequently, single dose administration of azithromycin has been recommended as an effective alternative.159 Appropriate stool precautions (particularly for hospitalized patients) are indicated, with proper disposal of contaminated linens and washing of hands. With respect to prevention, avoiding raw meats, particularly poultry, is recommended.

Currently, research is focusing on the identification and eradication of bacterial reservoirs. Additionally, molecular studies, leading to a better understanding of Campylobacter-associated diseases, are being conducted in order to improve prevention techniques and to offer alternative therapeutic approaches.182 The development of vaccines against C. jejuni has posed a significant challenge due to its microbiologic characteristics. Presently, phase I/II human trials are being conducted with preclinical experiments demonstrating promising data on a capsular conjugate vaccine.159

Yersinia Enterocolitis

Yersinia enterocolitica is a relatively recently recognized cause of enteric infection. Yersinia enterocolitis is of particular interest to the surgeon because of its prevalence and its occasional confusion with regional enteritis. A former name for the causative organism was Pasteurella pseudotuberculosis, again implying confusion with another bacterial infection that tends to involve the ileocecal region. Epidemics due to contamination of food, water, and milk have been reported.29 Y. enterocolitica most commonly affects infants, young children, and young adults.

The disease is caused by a facultative anaerobic, gramnegative coccoid bacillus resembling nonlactose-fermenting E. coli.78,312 It grows optimally in cold temperatures. The diagnosis is established by isolation of the bacteria from stool, blood, fluids, or tissue. However, Y. enterocolitica culture is not standard in most clinical laboratories and must be specifically requested.312 Biotyping and serotyping according to O antigens have been the most helpful of the epidemiologic techniques.78

After a median incubation period of 4 days, the organism may produce signs and symptoms of an acute enterocolitis. This may be accompanied by pharyngitis as a consequence of invasion of epithelial cells and the penetration of the intestinal mucosa, as well as the presence of the lymphoidabundant tonsils.306 Bloody diarrhea is frequently observed in addition to abdominal pain.268 Joint pain may also be a manifestation of this disease. Drainage of the bacteria into regional lymph nodes accounts for the systemic complications. Mesenteric lymphadenitis may develop from colonization of Peyer’s patches communicating directly with mesenteric lymph nodes. A syndrome simulating appendicitis is seen in 40% of patients—that is, fever, leukocytosis, right lower quadrant abdominal tenderness, and pain.78,268 However, a small number of patients with Y. enterocolitica will actually develop true appendicitis as a manifestation of the disease.283 The condition may produce generalized septicemia and “metastatic” abscesses in other organs. It can also present as a colonic abscess or as toxic megacolon.272,296 Sometimes the disease may pursue a chronic course for many weeks, particularly if not treated with appropriate antibiotics. Postinfection manifestations include erythema nodosum and reactive arthritis.78 Predisposing factors to the development of the infection follow:

cirrhosis

hemochromatosis

acute iron poisoning

transfusion-dependent blood dyscrasias

immunosuppression

diabetes mellitus

malnutrition78

Results of radiologic examination were evaluated in a review by Vantrappen and colleagues.312 A coarse, irregular, nodular mucosal pattern was seen in the terminal ileum; ulcerations were also noted. In contrast to Crohn’s disease, infection of the terminal ileum is usually confined to the mucosa and submucosa, and the characteristic “string sign” is absent. Endoscopic examination demonstrates signs of inflammatory disease in approximately one-half of the patients. Findings are nonspecific and variable, including aphthoid lesions within the cecum, as well as small round elevations in the terminal ileum with or without exudate.155

Recommended treatment includes antipseudomonal aminoglycosides, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, ceftizoxime, or ceftriaxone, but antimicrobial therapy has not been proven essential or necessarily efficacious in the uncomplicated situation.78 However, when systemic illness supervenes or when the patient is immunocompromised, doxycycline or trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole is advisable. Y. enterocolitica is generally resistant to penicillin and first generation cephalosporins. Sporadic resistance to macrolides and fluoroquinolones has been reported as well.155

Prevention of yersiniosis includes adequate treatment and handling of raw poultry, beef, and pork as potential sources of infection. Consumption of raw milk should be avoided and hand washing after using the toilet or diaper changes as well as after handling pets and animals is mandatory.220

Salmonellosis: Enteric Fever and Nontyphoidal Salmonellosis

Enteric Fever

Enteric fever is caused by Salmonella enterica, an anaerobic gram-negative bacillus, which includes serotypes S. typhi and S. paratyphi. It is transmitted via fecal-oral transmission among humans, its only reservoir, and occurs largely in areas with poor sanitation and contaminated water supplies. Its incidence in the United States has decreased significantly due to improvements in sanitary conditions, and it has mainly become a travelers’ disease within developed countries. However, it still remains a considerable disease burden in developing countries worldwide, particularly in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia.76 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), it is estimated that approximately 21 million people are affected annually; infection is associated with a 1% mortality rate.81 In recent years, the incidence of enteric fever caused by S. paratyphi A has increased substantially in Asia. This poses a significant health concern because the current available vaccines do not protect against S. paratyphi.200

The diagnosis of enteric fever based on clinical presentation is challenging, as the disease causes a constellation of

signs and symptoms that may easily mimic other febrile illnesses, bacterial or viral infections. A number of laboratory tests are available but are lacking in sensitivity and specificity. Within industrialized countries, blood culture is used frequently (an 80% sensitivity). Newer serologic tests have been developed based on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) and nucleic acid analysis, as well as multiplex PCR to detect both S. typhi and S. paratyphi. However, their successful clinical application remains to be seen.200

signs and symptoms that may easily mimic other febrile illnesses, bacterial or viral infections. A number of laboratory tests are available but are lacking in sensitivity and specificity. Within industrialized countries, blood culture is used frequently (an 80% sensitivity). Newer serologic tests have been developed based on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) and nucleic acid analysis, as well as multiplex PCR to detect both S. typhi and S. paratyphi. However, their successful clinical application remains to be seen.200

Completion of the S. enterica serovar typhi genome sequence has led researchers to new avenues of investigation into the biology of this pathogen. S. typhi produces extensive epithelial invasion along the small bowel and colon without destruction of the intestinal mucosa.193 The bacteria breach the mucosa and submucosa in areas of an inflammatory reaction, and an endotoxin is produced upon autolysis of the bacterial cell. If the organism enters the bloodstream, severe septicemia may result. Characteristics of this illness include fever, headache, delirium, splenic enlargement, abdominal pain, maculopapular rash, and leukopenia.208 Generalized hyperplasia of the entire reticuloendothelial system occurs, particularly in the Peyer’s patches of the ileum and solitary lymph follicles of the cecum.208

Of interest to the surgeon is the fact that acute cholecystitis may occur, which may progress to gangrene and perforation. Toxic megacolon and intestinal perforation can also complicate the disease, and on rare occasion, massive lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage can develop.110,115,208,252,323 The process is usually limited to the terminal 70 cm of ileum and proximal colon.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree