present with a CT scan or an ultrasound, which may have been performed for another reason, showing an abnormality in the pelvis or liver or other site of metastases.

Level of the tumor

Macroscopic appearance (ulcerated, polypoid)

Extent of circumferential involvement

Fixity

Degree of differentiation (histologic appearance)

Endorectal ultrasound

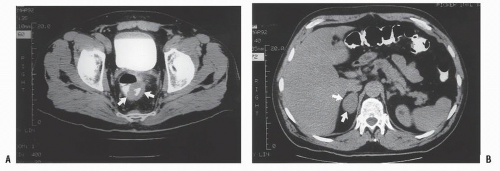

CT scanning

Magnetic resonance imaging

Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning

Presacral adenopathy

Body habitus

Gender

Age

Metastatic disease

Other systemic disease

Other conditions that may affect one’s ability to manage a colostomy (e.g., blindness, severe arthritis, mental incapacity)

presence or absence of venous or perineural invasion (PNI) in making the appropriate choice. Shirouzu and colleagues evaluated whether PNI is an independent prognostic factor in individuals who underwent curative surgery.566 There was a significant difference in local recurrence rates between those individuals with stage III lesions who were found to have PNI and those without PNI. In addition, the investigators found that patients with PNI and stage III lesions had a significantly lower survival rate. Nevertheless, the importance of PNI as an independent prognostic factor needs further evaluation (see also Chapter 23).

|

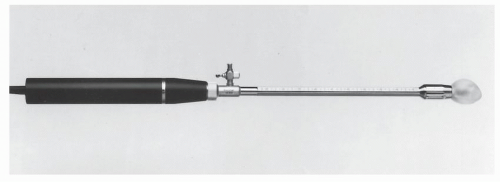

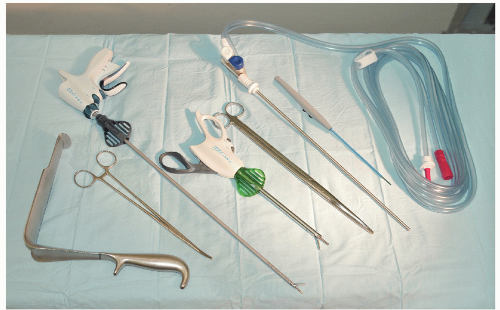

carefully explained to the patient and pertinent questions answered. The assistant enters the demographic data in the ultrasound computer as well as the frequency of the ultrasound probe and its focal range. The patient is placed in the left lateral position on the examining table. The study is preceded by a digital rectal examination to evaluate the size, fixation, location, and morphology of the rectal lesion. In most instances the use of a large-bore proctoscope serves several purposes. It allows visual examination of the rectal tumor with exact determination of its location both with respect to circumferential involvement of the rectal wall and the distance from the anal verge. Secondly, it allows suctioning of any residual stool or enema fluid that might interfere with the acoustic pathways of the ultrasound waves that may distort the image. Most important, however, it allows easy passage of the probe above the tumor to ensure that the transducer is advanced above the rectal lesion to allow complete imaging. This is significant since the lower border of a rectal cancer can differ in the depth of invasion than the center or upper portions of the cancer and lymph nodes in the perirectal region are often seen just above the level of the tumor. They will be missed if complete imaging is not obtained. Small distal lesions can be adequately imaged with the ultrasound inserted blindly and advanced above the lesion, but for most midrectal, bulky tumors the use of a proctoscope will facilitate the passage of the transducer.

|

of the rectal lumen in order to achieve optimal imaging of the rectal wall and perirectal structures. Some adjustments may have to be made on the gain of the ultrasound unit in order to provide better imaging. Occasionally, it is possible to perfectly depict all five layers of the rectum circumferentially, but usually only a portion of the rectal wall at a time will be optimally imaged. Minor adjustments will have to be made in the location of the probe relative to the rectal wall at various locations to optimally image all five layers clearly. Once optimal imaging of the rectal wall and surrounding structures has been achieved, the ultrasound probe is gradually withdrawn while carefully observing the screen and the images obtained. Several hard-copy images should be obtained for future reference through the use of a Polaroid image recorder. These images can be obtained by stopping the rotation of the transducer by depressing the activation/deactivation button and holding it longer, thus activating the recorder.

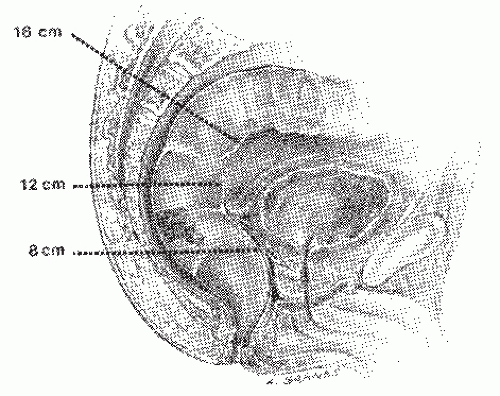

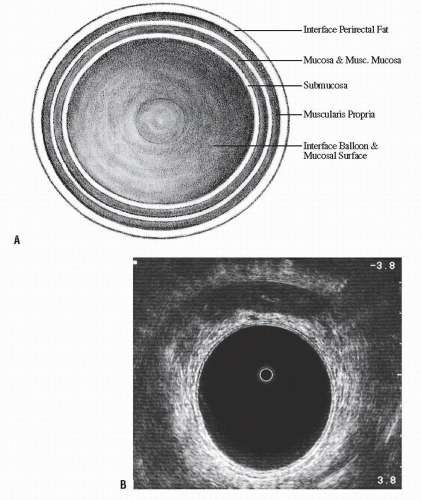

FIGURE 24-5. Endorectal ultrasound. A: Schematic diagram of normal rectal wall anatomic layers. B: Endorectal ultrasound imaging of normal rectum. |

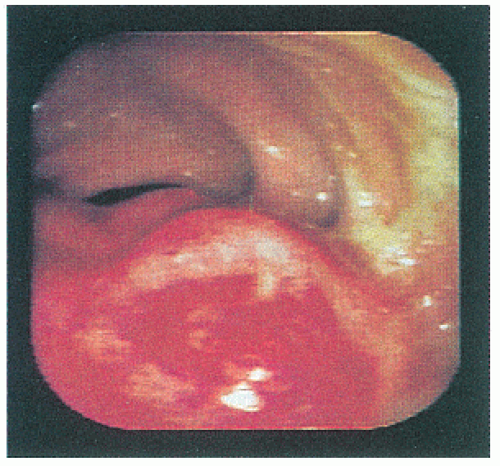

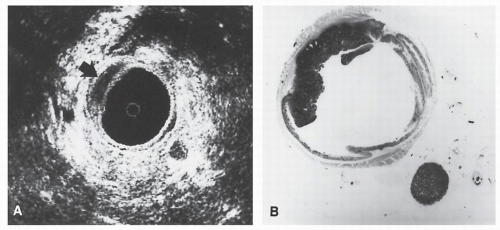

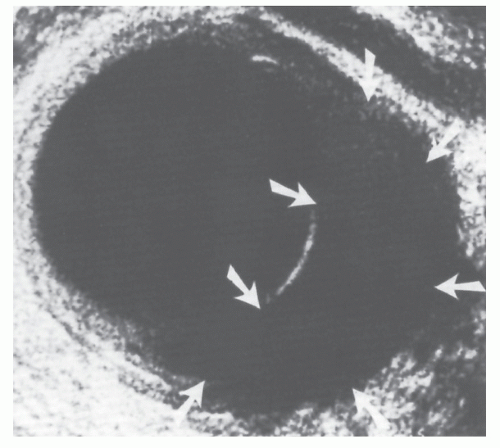

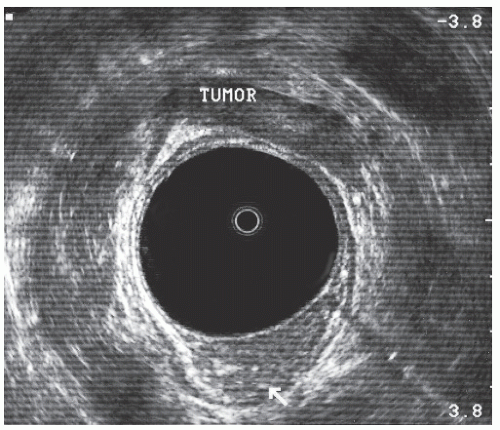

line represents the interface of the balloon with the mucosal surface of the rectal wall. The inner black line represents the mucosa and muscularis mucosa, whereas the middle white line corresponds to the submucosa. It is this middle white line that is the most crucial layer to visualize in order to determine whether the tumor is invasive.292 The outer black line corresponds to the muscularis propria, whereas the outer white line represents the interface between the muscularis propria and the perirectal fat. Once it has been ascertained that the middle white line is broken, then the presence of an invasive tumor has been confirmed. It is then a matter of determining the depth of invasion. Figure 24-6 demonstrates an ultrasound of a minimally invasive cancer with the corresponding resected, microscopic area. Figure 24-7 shows transmural involvement by tumor.

T Stage | Ultrasound Characteristics |

uT0 | Noninvasive lesion. Hyperechoic submucosal interface is intact. |

uT1 | Invasion of submucosa only. Hyperechoic middle white line is stippled and irregular but not disrupted. |

uT2 | Breaching of hyperechoic middle white lineindicates invasion of hypoechoic muscularis propria (Figure 24-8). Outer white line is intact. Deep uT2 lesions have a scalloped appearance. |

uT3 | Invasion through muscularis propria into perirectal fat (Figure 24-7). Outer (hyperechoic) white line (junction of muscularis propria with perirectal fat) is disrupted. |

uT4 | Extension into adjacent organ or structure (e.g., vagina, prostate, bladder, cervix, seminal vesicles). Plane between any of these structures and the rectum is obliterated. |

FIGURE 24-8. Endorectal ultrasound scan of a uT2 tumor. Note disruption of the middle white line with the intact outer white line. |

Fixed tumor

Evidence of ureteric obstruction

Invasion of adjacent structures (e.g., bladder, seminal vesicles, vagina)

Presacral adenopathy

Anal canal invasion

Ultrasound uT3 or uT4 lesion

Poorly differentiated histology

the risk of local recurrence.69,73,84,101,118,119 and 120,128,152,174,178,194,197,200,201,224,254,280,286,303,322,399,413,414,415,416,417 and 418,427,474,483,521,524,526,571,574,577,615,626 Some have stated that survival rates are better.181,605 Kandioler and coworkers observe that a tumor with a normal p53 genotype is predictive for response to preoperative short-term radiotherapy and increased patient survival.300 However, there remains disagreement whether preoperative radiation therapy has any effect on survival.204

|

|

|

|

patients who underwent preoperative radiotherapy followed by low anterior resection using historical controls, there was strong evidence for improved long-term survival.130 In still another prospective, randomized trial that was undertaken by the Medical Research Council Rectal Cancer Working Party in Birmingham, England, investigators used 40 Gy given in 20 fractions of 2 Gy over 4 weeks in those individuals randomized to preoperative radiotherapy.412 At 5-year followup, those who were randomized to radiation therapy had a statistically significantly lower incidence of local recurrence as well as fewer distant metastases. However, survival results were equivocal.

Patients with low bulky tumors

Those in whom the tumor is tethered or fixed

Patients whose preoperative ultrasound suggests extensive direct spread beyond the rectal wall and/or the presence of suspicious nodes

Where biopsy indicates a poorly differentiated or highgrade tumor

of ultimately performing a colostomy when he undertook a postmortem examination on an infant who died with an imperforate anus. He is quoted as stating, “… it would be necessary to make an incision into the belly, open the two ends of the closed bowel,… bring the bowel to the surface of the body wall where it would never close, but perform the function of an anus.”360 Colostomy, however, did not achieve an important role until Amussat (1839),9 a French surgeon, urged that it be the routine procedure for obstructing rectal cancer.386 For most of the 19th and into the 20th century, the stoma was placed in the inguinal or iliac region. This avoided entering the peritoneal cavity. Luke,379 however, was an exception. He was the first to bring the bowel out in the area of the rectus muscle, whereas Deaver134 was an advocate of lumbar colostomy.

|

|

excised the rectum for this condition.359 His was a transanal approach and, as such, was of necessity, used only for low-lying rectal lesions. This procedure and merely supportive care were the only available options. Modifications were introduced by von Volkmann,631 Cripps,116 and others, but the results of the perineal operation were poor. There was frequent incontinence, a high recurrence rate, and a high mortality rate.512

|

|

|

|

|

|

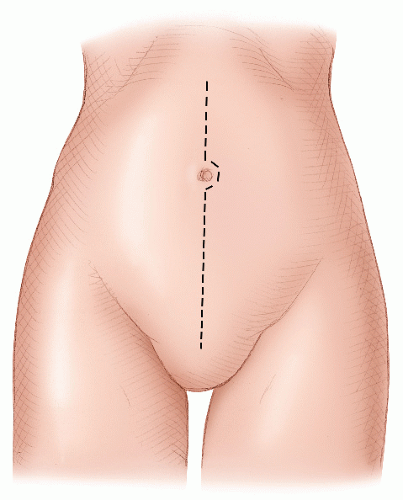

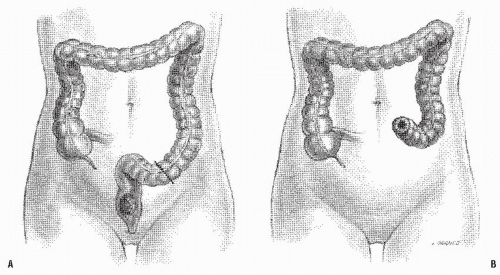

becoming the first person to perform an APR.127 In 1908, Miles described his modification of Czerny’s operation, placing emphasis on meticulous dissection and removing the zone of upward spread of the cancer (Figure 24-9).421 He concluded as follows:

|

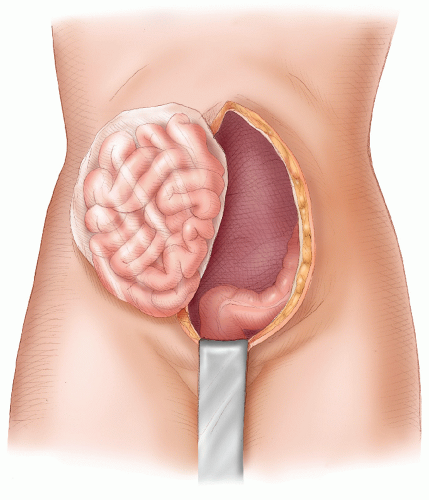

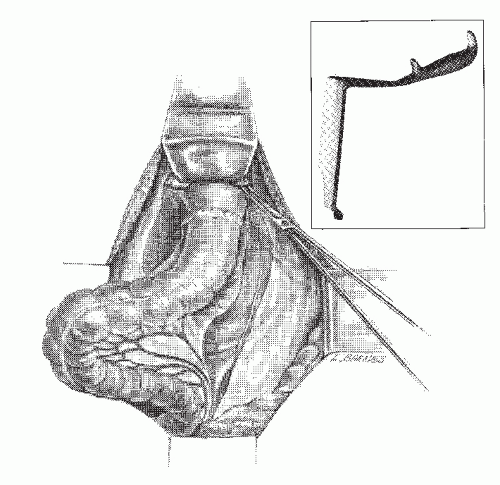

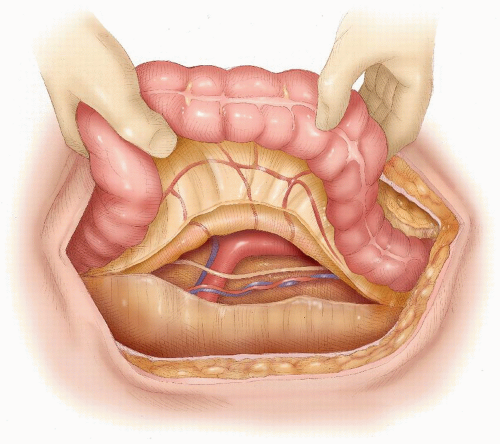

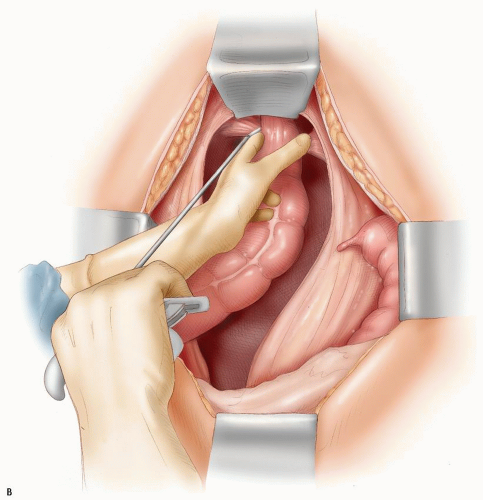

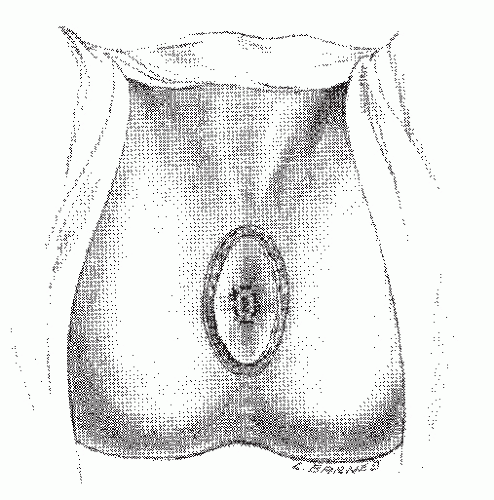

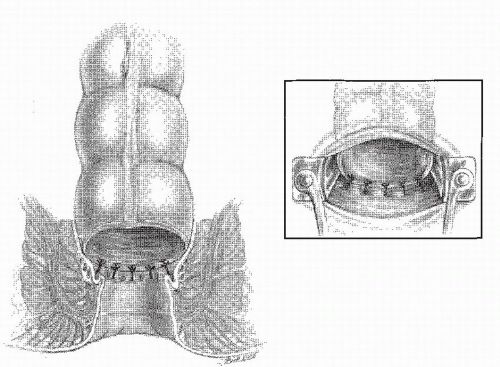

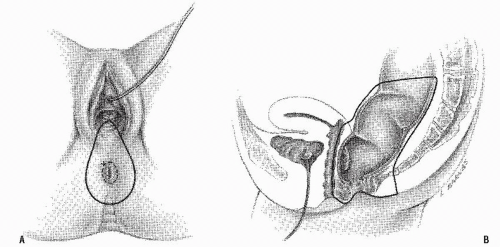

FIGURE 24-9. Carcinoma of the rectum. A: Extent of removal in classic abdominoperineal resection. B: The sigmoid colostomy is created in the left iliac fossa. |

in a steep Trendelenburg tilt, seldom took more than 35 to 40 minutes. Miles was quite prescient: the Miles resection has become the standard operation for the treatment of cancers of the low rectum. A presumably less radical but perhaps safer procedure was the attitude taken by Miles’ rival, Percy Lockhart-Mummery (see Biography, Chapter 12), who favored a perineal excision, preceded 2 or 3 weeks earlier by a minilaparotomy to determine that the growth was resectable.210 When this was the case, a loop-iliac colostomy was established.

|

|

|

surgeon has a good assistant.” By 1963, the Lloyd-Davies technique was the most commonly employed alternative at the St. Mark’s Hospital, and the operative mortality had been reduced to less than 3%.439 It is particularly helpful when one is confronted with a bulky or fixed tumor or a patient with a narrow pelvis. With all appropriate deference to Miles and to his statement that the operation takes no more than 1 hour and that his patients suffer “no more shock than after an ordinary perineal excision,”421 blood loss can be reduced and operative time decreased by using a two-team method. Interestingly, Miles’ resection as performed by Richard Cattell of the Lahey Clinic in Boston (see Biography, Chapter 31) was called by his assistants “the hour of charm.”

|

|

were as uneventful as an operation for a cold appendix. The conservation of a small cul-de-sac of the rectum above the sphincters did not present a particular problem, and follow-up 9 and 10 months later revealed the patients to be quite well.240

|

|

|

|

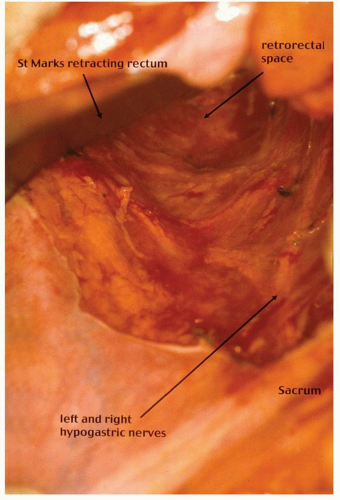

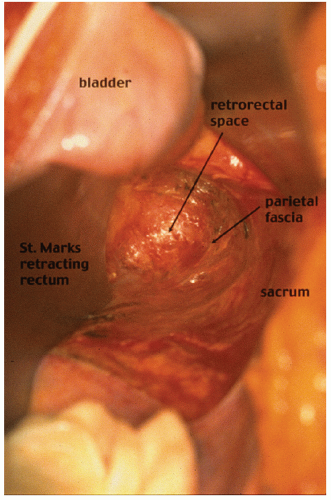

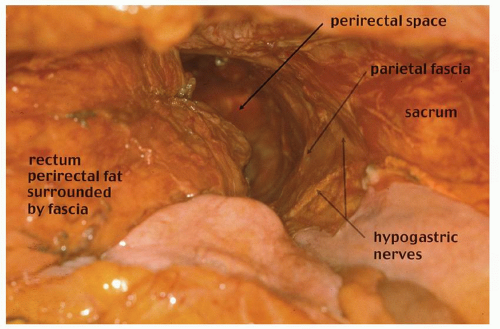

contemporary anatomy textbooks.96 Knowledge and understanding of this anatomy is the key to identifying the correct plane of mobilization when resecting the rectum for cancer. Indeed, this anatomy has been rediscovered by many surgeons over the past century who were unaware of Ionescu’s singular contribution. For example, Heald rediscovered this anatomy for himself and renamed and popularized the “retrorectal space” and plane as the “holy plane” in his operation of total mesorectal excision or TME.248 However, some would describe Heald’s use of the term “mesorectum” as a misnomer438 or simply incorrect.621 These authors reinforce the key feature, as described by Ionescu, that the perirectal fascia per se takes its origin from the endopelvic parietal fascia off the pelvic side walls to encapsulate the rectum and not from the peritoneum.621 In this manner, surrounded by loose lobulated fat, the rectum is cushioned and cocooned in a serofibrous fascial envelope, together with its lymphatics, vessels, and nodes. Superiorly, the perirectal fascia is continuous with the peritoneum of the pelvic mesocolon at the level of S3 and where there is abundant fat enclosed within. Inferiorly, at its lower third, there is only minimal fat present, and a plane exists between the perirectal fascia and Denonvilliers’ fascia, separating the rectum from the prostate and seminal vesicles. This plane must be recognized in order to avoid unnecessary bleeding from the prostatic venous plexus or damage to the cavernous nerves when mobilizing the rectum anteriorly.358 The key is to dissect behind Denonvilliers’ fascia whenever possible, unless there is strong suspicion of direct involvement by tumor.358

|

if one is strongly motivated to reestablishing intestinal continuity, it can virtually always be accomplished. The obvious question is not can you put the bowel together, but should you. Table 24-1 summarizes the various procedures and the method of reconstruction.

TABLE 24-1 Options for Low-Lying Rectal Cancer | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

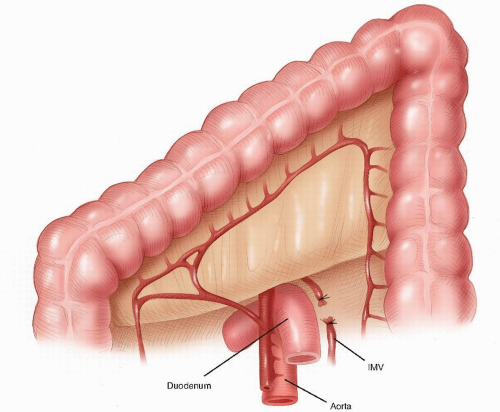

A total anatomical dissection (TAD) with mobilization along anatomical planes65

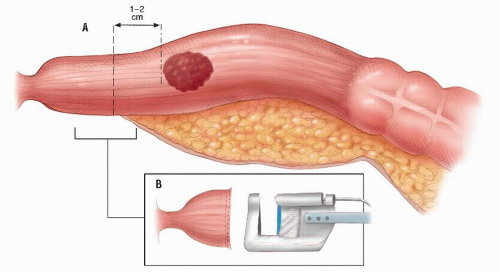

Achieving a distal clearance margin of at least 1 cm

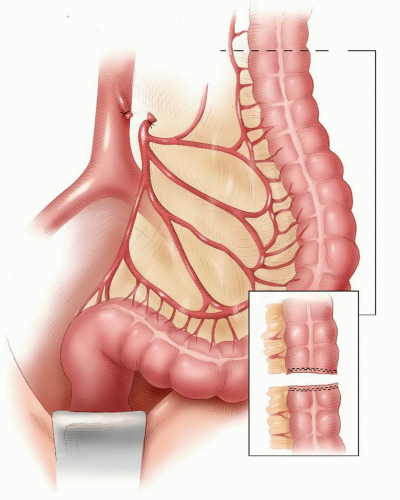

Mobilizing the proximal colon, including the splenic flexure, and division and ligation of the inferior mesenteric vein at the lower border of the pancreas to ensure a tension-free anastomosis

Ensuring a good arterial blood supply to the segment of proximal colon that will be anastomosed to the rectum

Ligation and division of the inferior mesenteric artery close to its origin from the aorta

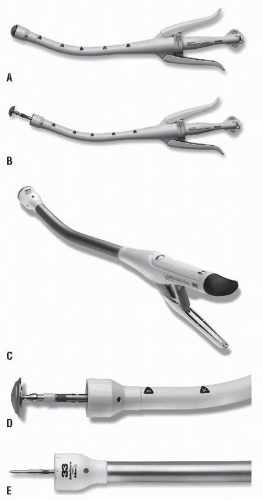

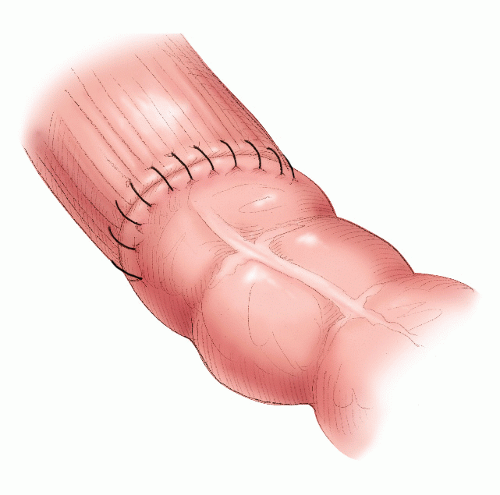

An anastomotic technique that ensures circumferential seromuscular bites

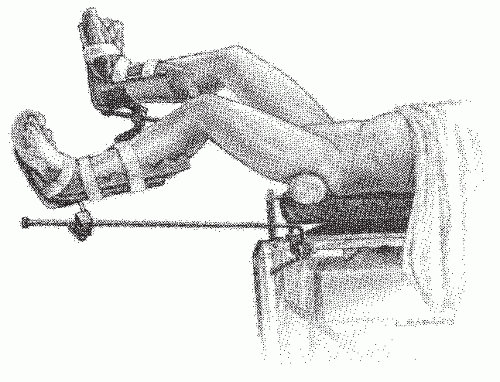

vein thrombosis. The abdomen is shaved. A urinary catheter is inserted, and when indicated, cystoscopy with insertion of ureteric catheters is performed by a urologist. The surgeon stands on the left side and the assistant stands opposite. A second assistant may stand between the legs.

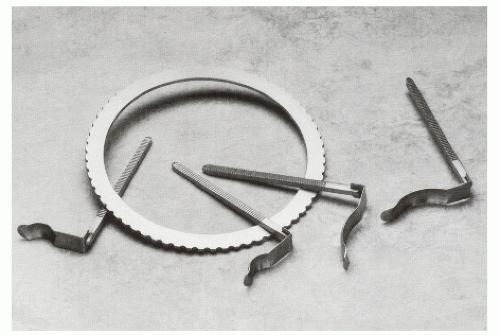

FIGURE 24-14. Perineolithotomy position with Allen’s stirrups (earlier version). The thighs are abducted and extended. |

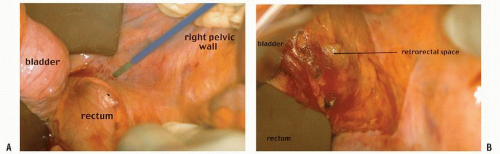

FIGURE 24-18. An incision is made along the line of reflection of visceral onto parietal peritoneum in the right mid-pelvis (A). Air is introduced into the retrorectal space (B). |

FIGURE 24-21. Pelvic dissection. Hypogastric nerves are clearly seen. Rectum, perirectal fat (with intact perirectal fascia) are separated from sacral parietal fascia. |

FIGURE 24-22. Congenital adhesions between the sigmoid mesocolon and left lateral wall are dissected. |

FIGURE 24-24. Anterior dissection. Incision is made strictly along the line of reflection of the rectal visceral peritoneum onto the peritoneum, covering posterior vagina or prostate. |

FIGURE 24-25. Anterior dissection behind the vagina (A) or prostate (B) posterior to Denonvilliers’ fascia. |

FIGURE 24-26. Harmonic scalpel is used to divide the “lateral ligaments” and neurovascular bundles on the right (A) and on the left (B). (continued) |

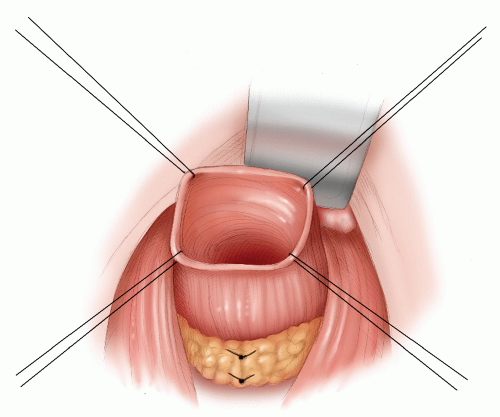

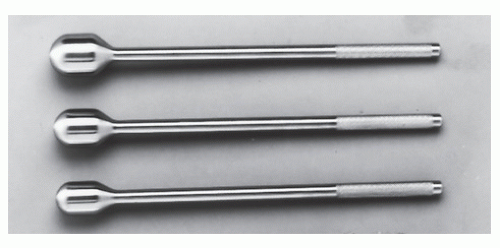

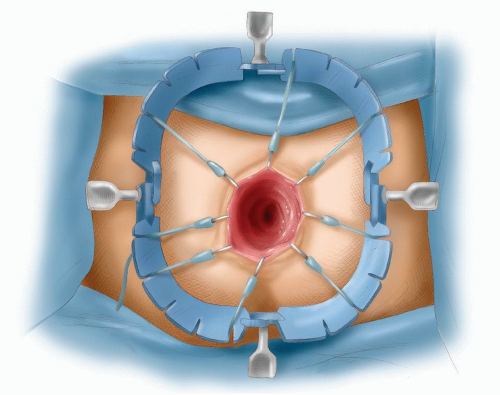

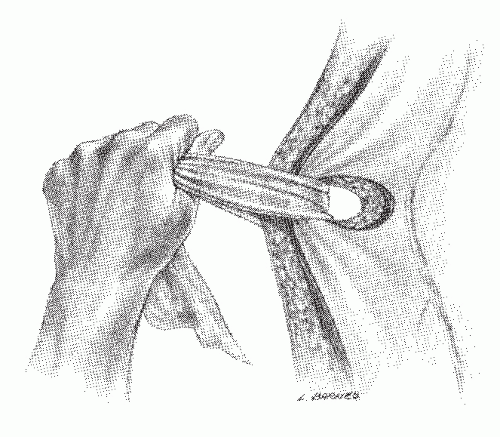

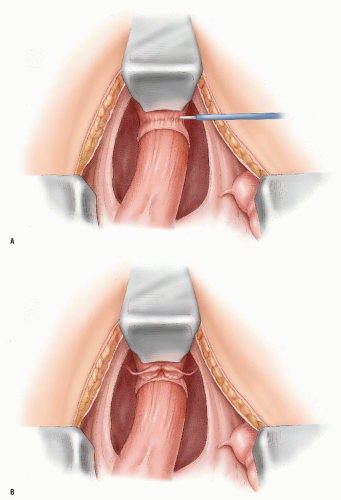

there is the risk of a straight needle injuring structures on the lateral walls as it enters or exits the clamp. Alternatively, a hand-sewn purse string can be used (Figure 24-30).

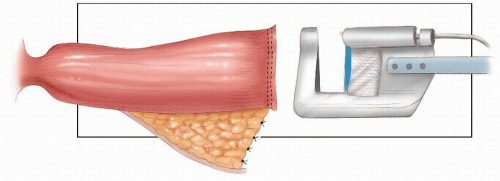

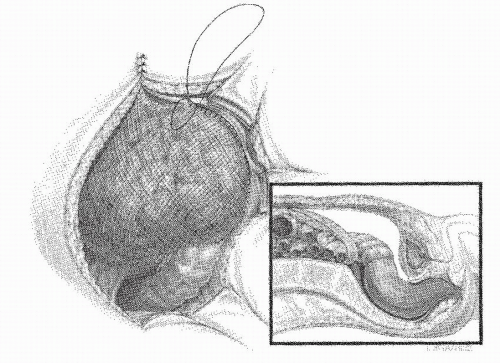

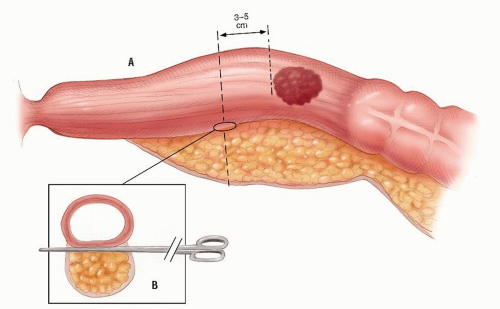

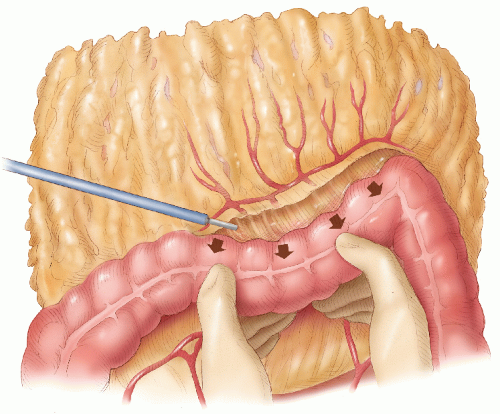

FIGURE 24-27. Division of perirectal fat for a tumor in the upper third of rectum. Inset: Opening the plane between the rectum and the perirectal fat. |

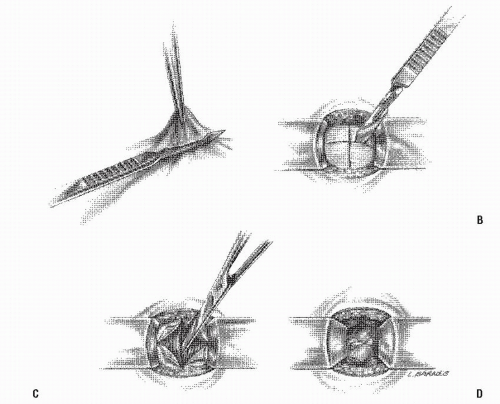

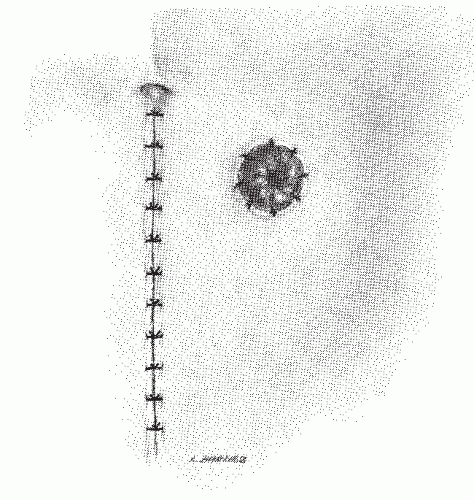

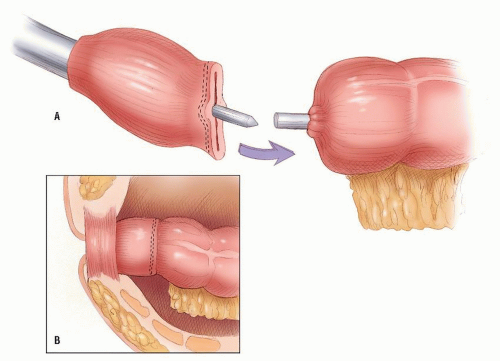

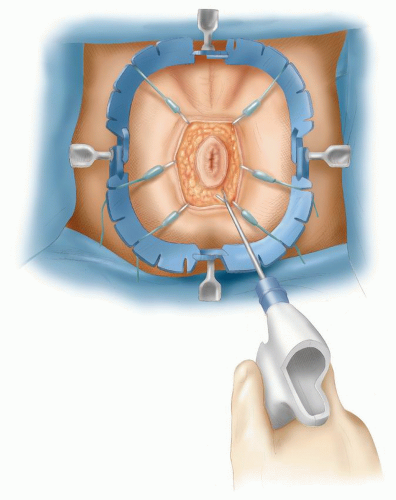

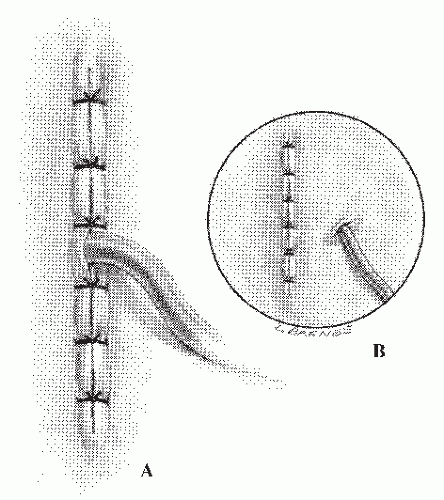

FIGURE 24-29. Circular-stapled anastomosis. A: Hand-sewn purse-string suture placed using “weaving” technique. B: Purse-string applicator employed on an inverted rectal stump. |

FIGURE 24-30. Circular-stapled anastomosis. A hand-sewn purse-string suture is placed in the rectal stump. |

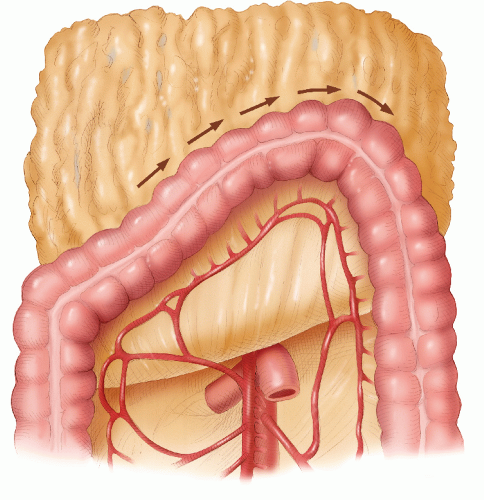

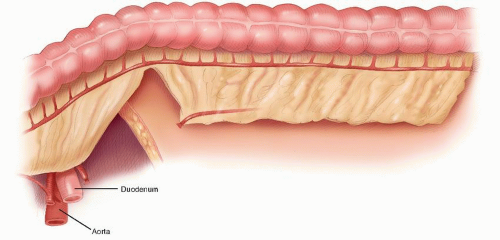

Mobilizing the splenic flexure

Ligating and dividing the inferior mesenteric vein at the lower border of the pancreas

Unfolding the splenic mesentery

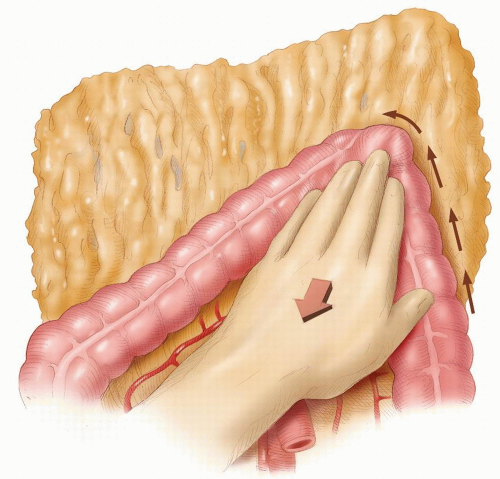

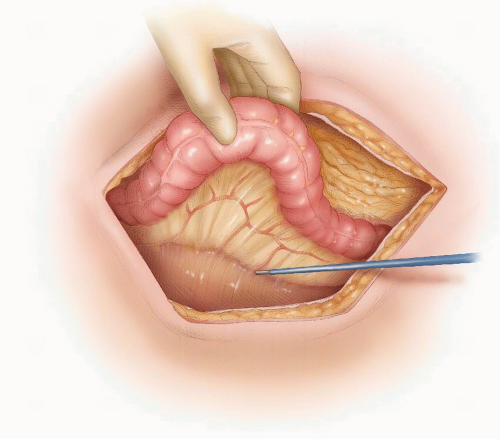

side. This is a dangerous maneuver that can tear fine adhesions between the omentum and the splenic capsule, resulting in injury to the spleen. The assistant gently retracts the distal transverse colon downward, and the greater omentum is retracted caudally (Figure 24-35). Sharp dissection then allows access into the lesser sac. The dissection continues toward the splenic flexure strictly in that avascular plane (Figure 24-36). Attention is then directed to the upper descending colon, which is retracted with the left hand (Figure 24-37). With diathermy in the right hand, the adhesions between the colon and the lateral abdominal wall are divided to meet the line of dissection of the distal transverse colon. The descending colon is thus mobilized to the midline.

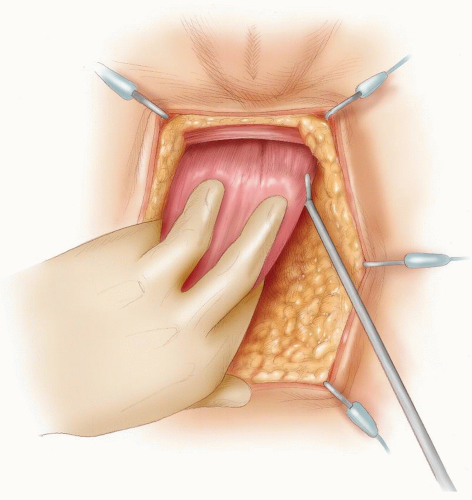

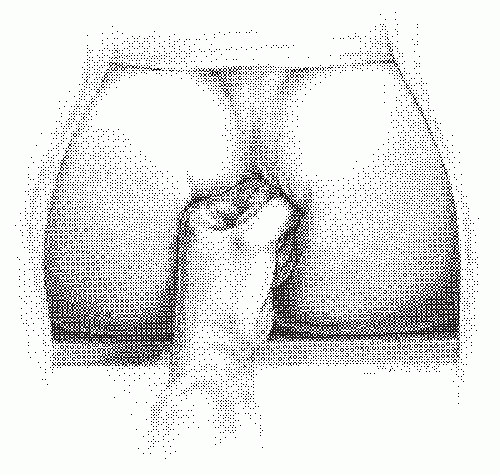

FIGURE 24-33. Pressure on the perineum by the fist or some other blunt object facilitates the placement of sutures into the rectal remnant. |

FIGURE 24-35. Mobilization of splenic flexure. The assistant holds the distal transverse colon down, and the lesser sac is entered. |

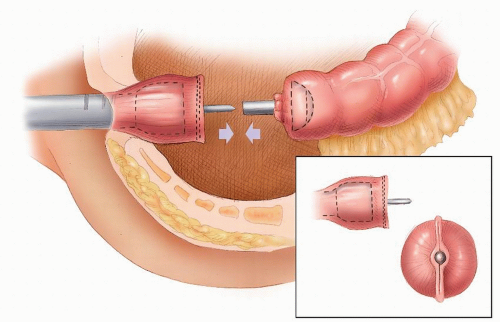

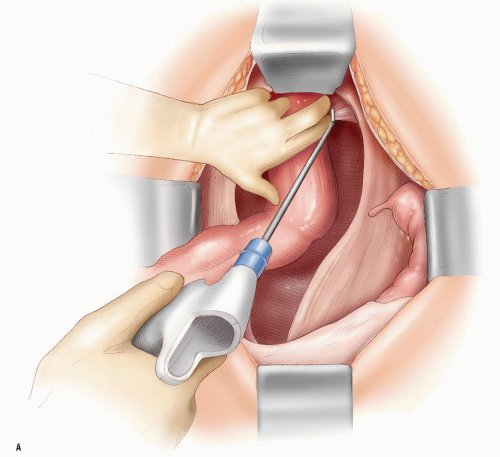

advance the trocar tip through the staple line (Figure 24-45), but some surgeons like to penetrate the adjacent bowel. It is critical, however, to incorporate the linear staple line.

put on the proximal colon by exteriorizing the transverse colon; there is no risk of injuring the vital marginal vessels of the proximal colon either when the colostomy is being constructed or when it is closed; and if a planned temporary stoma needs to be permanent, a loop ileostomy is easier to manage. Moreover, there is a lesser incidence of prolapse and parastomal herniation with a loop ileostomy.

took the word “total” in TME quite literally, performing unnecessary low and ultralow anterior resections when a high anterior resection would have sufficed. This resulted in a number of avoidable complications after low anastomoses, of which anastomotic leakage was the most worrisome. Karanjia and colleagues reported on the Basingstoke experience of 219 patients who underwent a TME for a tumor between 3.5 and 15.0 cm from the anal verge; an anastomotic leak rate of 17.4% resulted.302 Hainsworth and coworkers questioned the use of TME for upper third tumors in view of the high morbidity rate following this operation in their patients.233 The term TME has, however, taken hold. Today, it tends to refer to dissection of the rectum along the same anatomical planes as were originally described by Jonnesco (see earlier Biography), although many would now question the need to perform a TME for cancers of the upper rectum or rectosigmoid.352,372 From this concern has arisen the terms “partial” or “tailored” TME, wherein the mesorectum is divided 3 to 5 cm below the tumor. This shifts the emphasis to clearly identifying the retrorectal space and the perirectal fascia and not to the complete removal of the perirectal fat or “mesorectum” for tumors at all levels of the rectum.

FIGURE 24-46. The anvil and head are approximated, and the staples are fired to form the anastomosis (inset). |

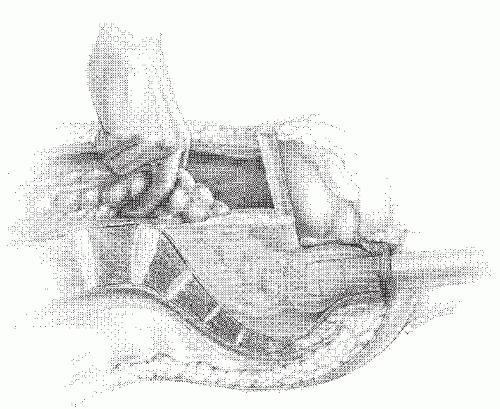

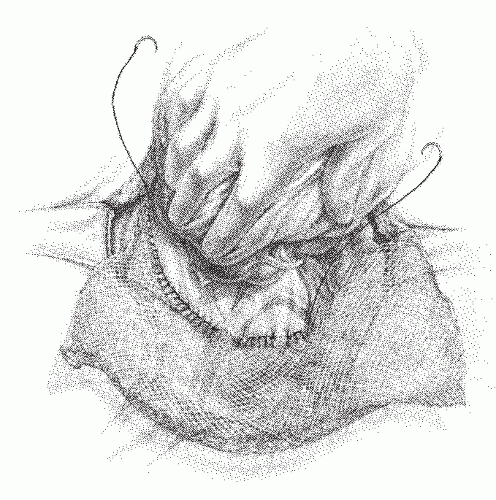

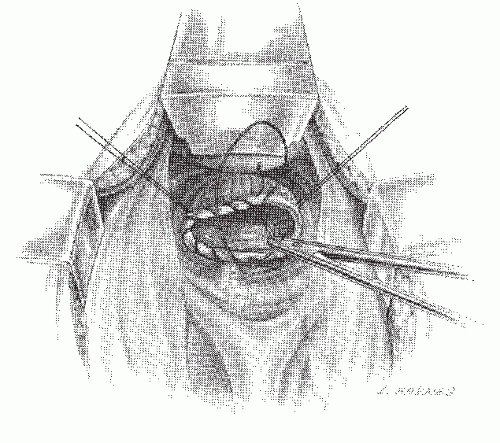

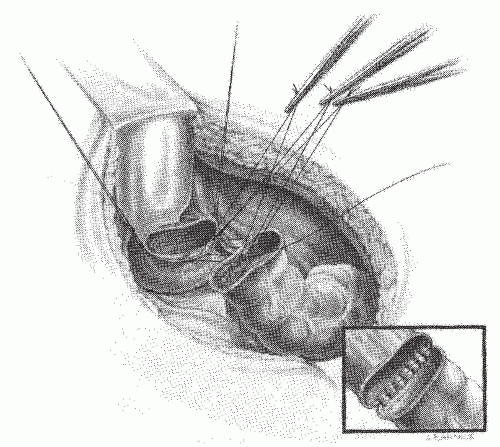

FIGURE 24-48. Hand-sewn rectal anastomosis. Sutures are initially placed in the posterior row but not secured. The inset demonstrates the posterior row completed. |

|

report incorporating key clinical and pathologic features from the findings at operation and the examination of the surgical specimen as a basis for appropriate multimodality treatment for the individual patient.98

recognized staging classifications,133 for the purpose of this chapter, the results tabulated are summarized using the TNM system.143

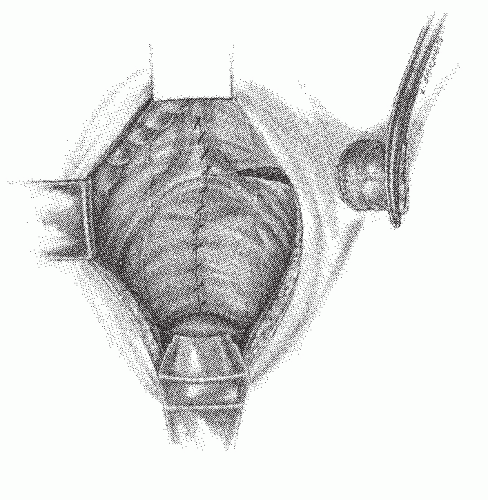

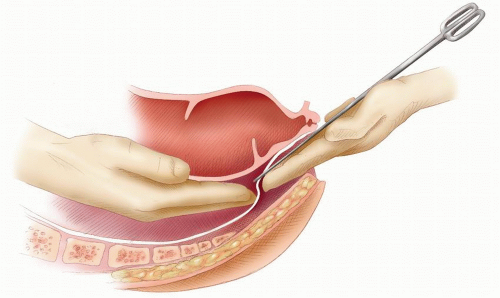

FIGURE 24-51. Foley catheter in proximal colon with balloon inflated, pulling colon down to anus to complete the coloanal anastomosis. |

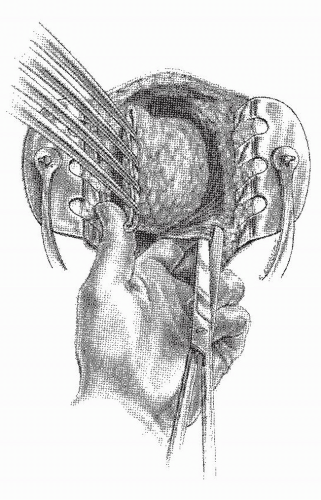

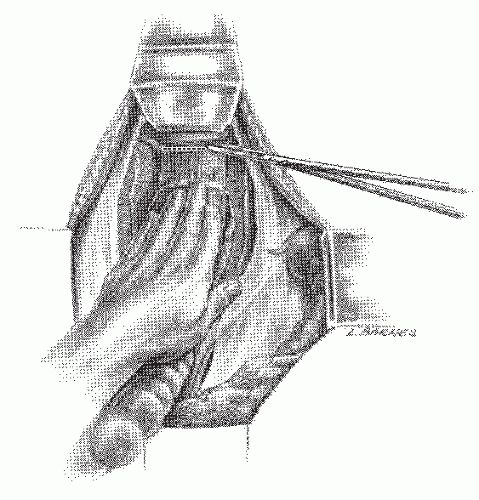

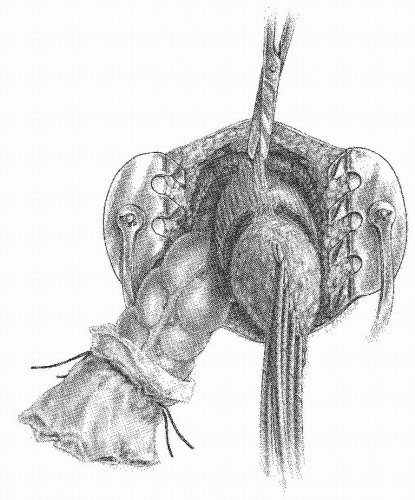

divide the muscle (Figure 24-61). The left index finger is similarly used to identify the right levator muscle, and the wave instrument is used to divide the muscle on the right side. Attention is then directed to the pubococcygeus and the puborectalis parts of the levator muscle. The muscle is divided with the Wave Harmonic scalpel from lateral to medial on either side. Branches of the inferior hemorrhoidal vessels are in close proximity to the puborectalis and can cause troublesome bleeding. Simply dividing the muscle with diathermy usually does not achieve adequate hemostasis. However, I have found that this can be achieved with the Wave Harmonic scalpel (Figure 24-62). Dissection between the rectum and prostate or vagina can now begin. The abdominal surgeon’s fingers can be used to guide the perineal surgeon. The perineal surgeon’s left hand is used to retract the rectum down, and the diathermy is used to dissect in the plane between the rectum and the prostate in males. The rectourethralis muscle on either side is divided (Figure 24-63); the dissection continues until the abdominal surgeon’s fingers are met, posterior to Denonvilliers’ fascia; and the dissection breaks into the pelvic cavity. By remaining in this plane, injury to the urethra is avoided. Another method of performing the anterior part of the dissection is to deliver the specimen through the perineum; once the posterolateral part of the dissection is performed, the specimen can be passed to the perineal surgeon who then retracts the specimen downward to better identify the anterior plane of dissection (Figure 24-64). In females, the anterior plane of dissection is between the rectum and the posterior wall of the vagina. If the tumor has invaded the posterior wall of the vagina, then the Wave Harmonic scalpel can be used to excise en bloc a portion of the vaginal wall. If the Harmonic scalpel is not available, then the vaginal wall has to be oversewn with an interlocking suture to prevent hemorrhage (Figure 24-65). The wound is closed in layers and drained through the vagina (Figure 24-66).

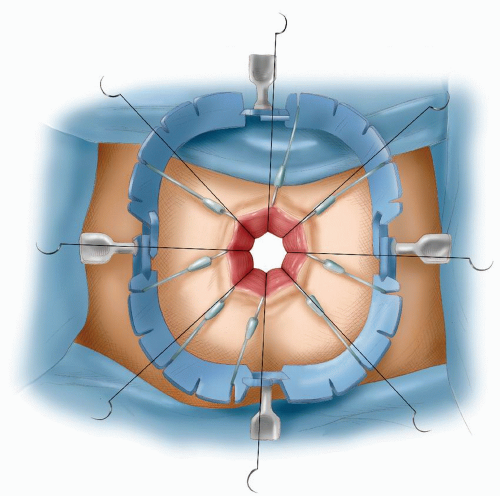

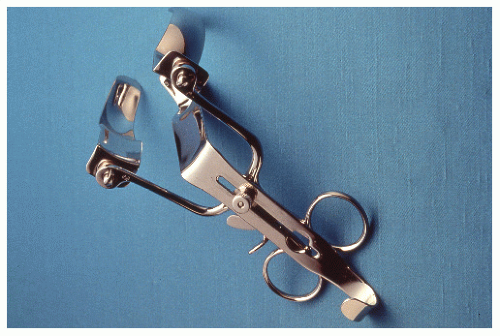

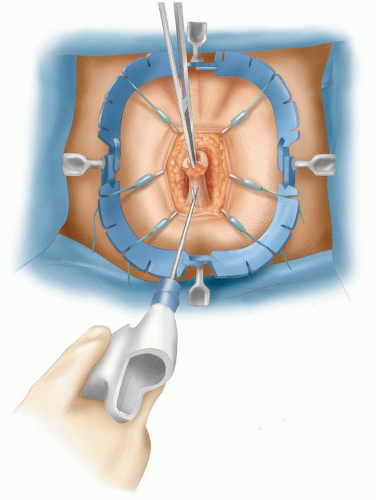

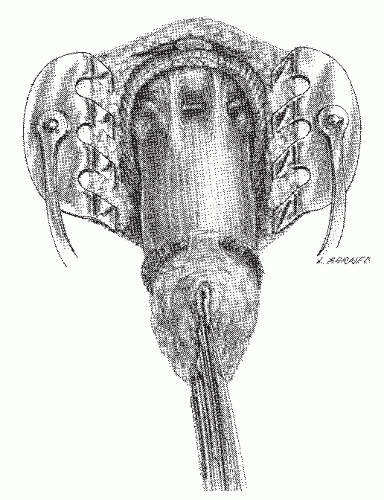

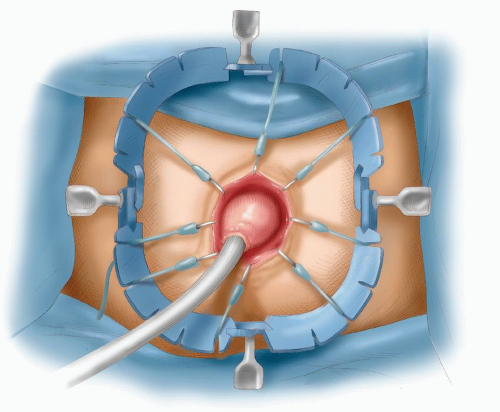

FIGURE 24-56. A Parks retractor facilitates the insertion of sutures (inset) in creating a coloanal anastomosis. |

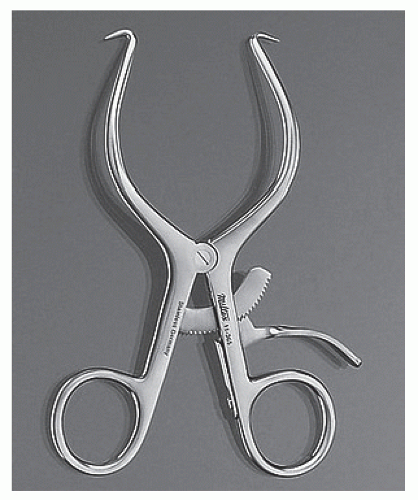

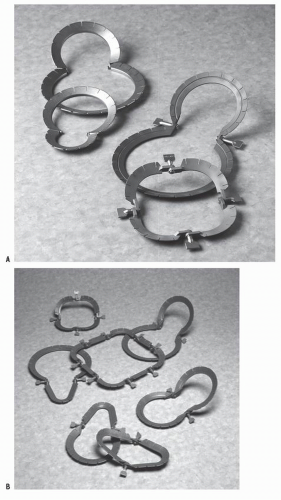

FIGURE 24-58. Perineal dissection. Lone Star retractor in place. Wave Harmonic scalpel is used to deepen incision. |

FIGURE 24-60. Perineal dissection. Identifying Waldeyer’s fascia and confirmation of the plane of dissection as the two surgeons’ fingers touch. The scissors facilitates their joining. |

before the patient is turned over for the perineal dissection. Although repositioning the patient is cumbersome, this position can achieve better exposure and access to the perineal anatomy. It is also more comfortable for both surgeon and assistant. Although I have occasionally used this technique, it is not routine in my practice.

two leaves together in the midline (Figure 24-71). It is thought that closure reduces the risk of small bowel obstruction and that it may be useful in patients in whom postoperative radiotherapy may be contemplated. There is, however, no clear evidence to support this. On the contrary, there is a theoretical risk that a gap can occur in the suture line through which a loop of small bowel may herniate and cause obstruction. Furthermore, during mobilization of the parietal peritoneum from the lateral pelvic wall, the ureters could be injured. However, in the few patients in whom postoperative radiotherapy is contemplated, there is a potential risk of radiotherapy injury to the small intestine if it were to fall into the dissected pelvis. For this reason, several techniques have been proposed to reconstruct the pelvic floor. In view of the fact that adjuvant therapy is now mainly given preoperatively, closing the pelvic floor is not essential nor is it practiced routinely.

on limited, selected patient series. Furthermore, it has to be recognized that ELAPR, with or without sacrectomy, results in a larger perineal wound. This may require various plastic surgical procedures to close, potentially leading to a higher risk of perineal wound complications.37,268

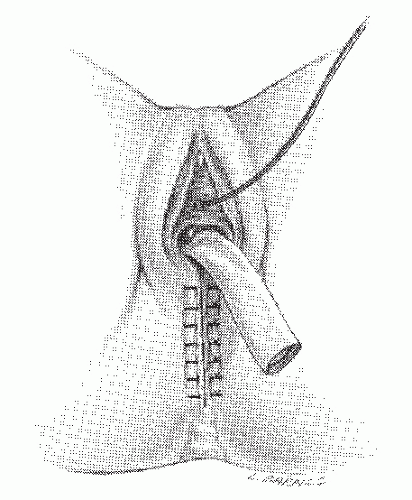

FIGURE 24-64. Perineal dissection. The proximal colon has been delivered through the pelvic defect. The rectourethralis muscle and the visceral fascia are the only structures remaining to be divided. |

FIGURE 24-65. Perineal dissection in women. A: Outline of the incision for excising the posterior vaginal wall. B: Lateral view showing the extent of removal. |

FIGURE 24-67. Perineal dissection. The wound is closed primarily, and the pelvis is drained, either through the incision (A) or through a stab wound (B). |

FIGURE 24-72. Implantation of mesh for postoperative radiation. The mesh is anchored to the sacral promontory. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree