Colorectal Polyps

James M. Church

Matthew F. Kalady

If people are falling over the edge of a cliff and sustaining injuries, the problem could be dealt with by stationing ambulances at the bottom or erecting a fence at the top. Unfortunately, we put far too much effort into the provision of ambulances and far too little into the simple approach of erecting fences.

—DENIS BURKITT

A polyp is an abnormal projection above an epithelial surface. Polyps project from the surface of epithelium in many different organs, but this chapter discusses colorectal polyps and associated diseases. Colorectal polyps are diverse in appearance and histology. They may be pedunculated, sessile, or even depressed lesions with size varying from 1 to 2 mm to more than 10 cm. Polyp is merely a descriptive term and not a histologic diagnosis. Histologically, any of the tissues present in the colon can appear as a polyp including fat (lipoma), nerve (ganglioneuroma, schwannoma), muscle (leiomyoma), lymphoid tissue, and fibrous tissue (fibroma). Normal mucosa can look like a polyp, either just because it is raised or because it is made to be raised by peristalsis (mucosal prolapse), surrounding inflammation (pseudopolyp), or suction. Inflammation can cause polyps to form, in particular the very vascular granulation polyps that are found at recent anastomoses and in chronic colitis. Repeated trauma can also produce polypoid mucosa, as seen in variants of the solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. However, this chapter is dedicated to a discussion of the three most common and most important types of polyps found in the large intestine—those arising from overgrowth of epithelium. These include serrated (hyperplastic or metaplastic), hamartomatous, and adenomatous. Each polyp type has unique morphologic, clinical, and histologic traits and is associated with its own polyposis syndrome. These will be addressed later in this chapter.

▶ SERRATED POLYPS

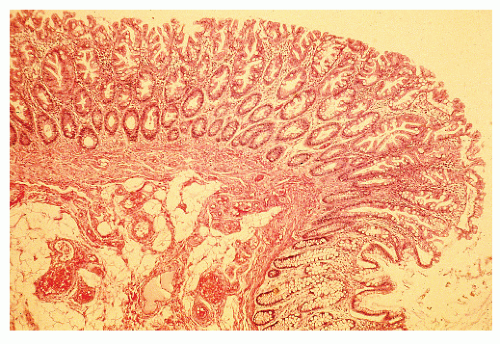

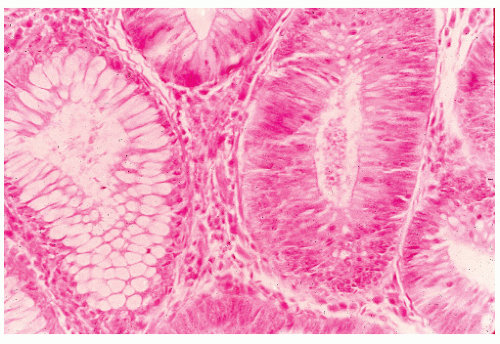

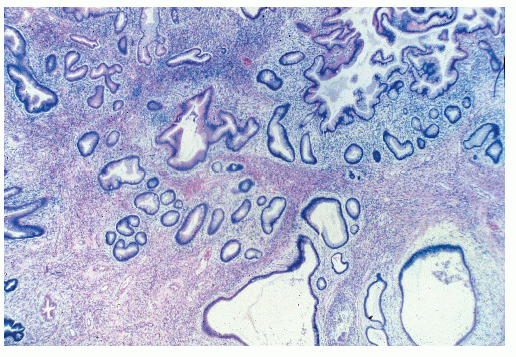

In 1934, Westhues described a nonneoplastic mucosal lesion that came to be known in the United States as a hyperplastic polyp.343 In England, polyps of similar histology were called metaplastic, a term introduced by Morson in 1962.226 For the next 70 years, hyperplastic polyps were widely believed to be completely benign with no malignant potential. A few authors were suspicious of the role for hyperplastic polyps in colorectal carcinogenesis,165 however, and in 1988 Fenoglio-Preiser and Longacre introduced the term serrated adenoma to describe polyps in which hyperplastic and adenomatous epithelium coexisted.99,210 Since then, “serrated” has been increasingly used to refer to a family of lesions in which the crypt epithelium is thrown into serrations, as in a sawtooth pattern. Serrated polyps of the colon and rectum include all that were previously known as “hyperplastic.” The World Health Organization (WHO) classification describes three main types of serrated lesions in the large intestine: hyperplastic polyp (HP), sessile serrated adenoma (also called sessile serrated polyp—SSA/P), and traditional serrated adenoma (TSA).303 All of these polyps feature serrated epithelium but are distinguished based on crypt architecture and abnormalities of proliferation. HPs have normal-appearing crypts and a restricted basal proliferative zone (Figure 22-1), whereas SSA/Ps show distorted crypts and an irregular proliferative zone, which can be expanded or contracted (Figure 22-2). TSAs show ectopic or budded crypts with proliferation within the buds, but also feature adenomatous type dysplasia.302 Although HPs are generally not precursors of cancer in themselves, they may serve as markers of a colon at risk for developing colorectal cancer. SSA/P and TSA, however, are definitely precursors of cancer. This changes the clinical approach to these lesions from “ignore” to “remove and follow.”

BASIL MORSON (1921-PRESENT)

|

Basil Morson was born November 13, 1921. He enrolled in Oxford University in 1939 with the intent of studying medicine. However, in 1943 he deferred his degree and joined the British Royal Navy as an ordinary seaman. Within 6 months, he was promoted to sublieutenant. Upon demobilization, Morson returned to Oxford and qualified as a physician in 1949 before gaining his doctorate in 1955 with his thesis on intestinal metaplasia of the gastric mucosa. He ultimately succeeded Cuthbert Dukes as consultant histopathologist at St. Mark’s Hospital, London, and served in that position for 30 years, 1956 to 1986. Among his notable academic achievements are a detailed description of the adenoma-carcinoma sequence (with Tetsuichiro Muto), the first description of large bowel Crohn’s disease (with Sir Hugh Lockhart-Mummery), and the standard book of British gastrointestinal pathology, known colloquially as Morson and Dawson, now on its fifth edition. He is recognized throughout the world as the father of the specialty of gastrointestinal pathology. A prolific writer, he has been honored by both colleges and medical societies. He was made a fellow both of the Royal College of Surgeons of England and the Royal College of Physicians. He was awarded the John Hunter Medal of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1987 and served as president of the Proctology Section of the Royal Society of Medicine, president of the British Society of Gastroenterology, (BSG—the first pathologist so to be honored), and both vice president and honorary treasurer of the Royal College of Pathologists. He was made CBE (Commander of the British Empire) just after his retirement in 1987. More recently, he received the President’s Medal of the British Division of the International Academy of Pathology (2005), a new award that has been introduced to honor a member of the division who has made an outstanding contribution to pathology education. The inaugural recipient was Basil Morson. Morson has left an indelible mark in gastrointestinal education in both pathology and clinical circles, the latter exemplified by the fact that he was the first pathologist to be elected as president of the British Society of Gastroenterology. Even though he has been retired officially for more than 20 years as of this writing, he continues to be active in gastrointestinal pathology education and is a regular attendee at the BSG meetings. At that gathering, there is an annual Basil Morson Lecture, given in his honor by eminent gastrointestinal pathologists from the United Kingdom and abroad. (Courtesy of Robin K.S. Phillips.)

Genetics

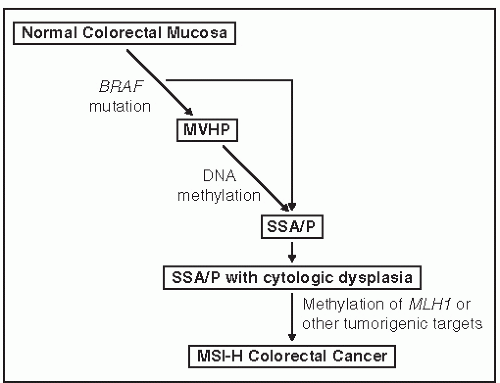

Serrated polyps have a different genetic origin from that of adenomas and lead to cancers with a different and specific genetic makeup. Although every colorectal cancer is genetically unique, there are three basic genetic mechanisms by which they arise: chromosomal instability (CIN), DNA mismatch repair deficiency, and DNA promoter hypermethylation. Methylation underlies serrated polyps. DNA methylation is a normal mechanism by which gene expression is controlled. Methylation inhibits expression, so hypermethylation suppresses gene expression, and hypomethylation amplifies it. DNA is normally methylated at CpG dinucleotides, which tend to be concentrated in promoter regions of genes. Promoter methylation abrogates gene expression, and if the gene is a tumor suppressor gene, it encourages carcinogenesis. Widespread DNA hypermethylation is evidence of the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP)341 and is involved in about 23% of all colorectal cancer.287 CIMP cancers arise from serrated polyps, in particular SSA/P. Figure 22-3 shows one suggested genetic pathway causing serrated lesions in which the early event is a mutation in BRAF, leading to the formation of HPs. The addition of methylation produces an SSA/P that can also develop dysplasia. Promoter methylation of the mismatch repair gene MLH1 seems to be the final step leading to CIMP cancer in SSA/Ps. This creates an overlap between the mismatch repair (MMR) dysfunction and methylator mechanisms of carcinogenesis because some CIMP cancers do not express MLH1 and are microsatellite unstable.7 An alternative, albeit less prevalent serrated pathway, involves a KRAS mutation as the initiating event with a traditional serrated adenoma as an intermediate lesion. This pathway is believed to yield a microsatellite stable colorectal cancer.

Clinical Profiles

The three types of serrated polyps have different clinical profiles. Hyperplastic polyps are usually found in the rectum and sigmoid colon, often at the summit of mucosal folds and on the apex of the valves of Houston. At least one HP is found in 12% of colonoscopic examinations, although this

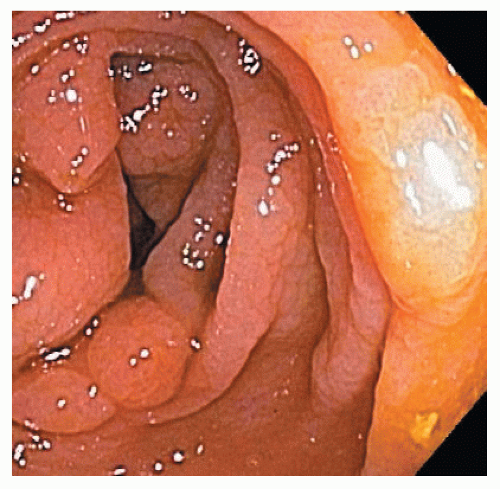

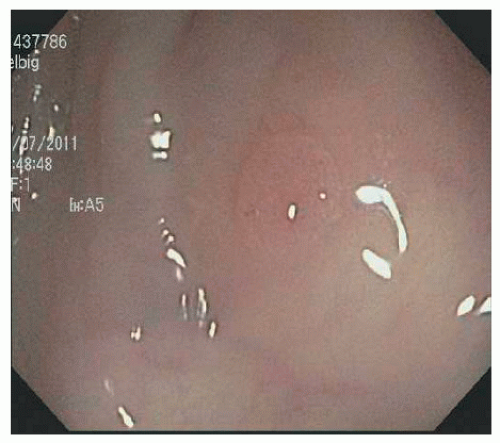

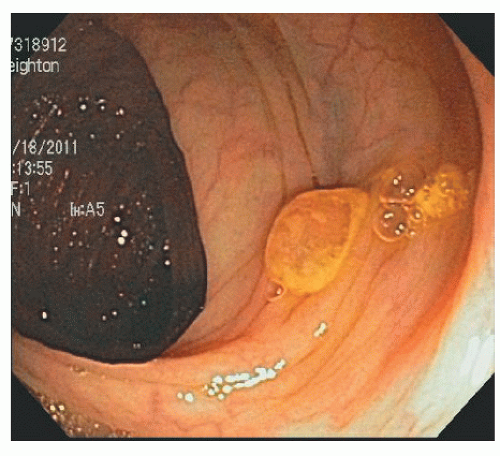

is likely to be an underestimate because they can be difficult to see and often may be ignored.140 There are few data on detection rates or endoscopic recognition of any of the serrated polyps, and those that are available generally do not distinguish between HP, SSA/P, or TSA. HPs are often multiple. More than 20 polyps qualify for the diagnosis of serrated polyposis.303 The majority of HPs are usually small (2 to 5 mm), are often pale or whitish, and sometimes have a translucent appearance that causes them to disappear when the colon is insufflated with air (Figure 22-4).

is likely to be an underestimate because they can be difficult to see and often may be ignored.140 There are few data on detection rates or endoscopic recognition of any of the serrated polyps, and those that are available generally do not distinguish between HP, SSA/P, or TSA. HPs are often multiple. More than 20 polyps qualify for the diagnosis of serrated polyposis.303 The majority of HPs are usually small (2 to 5 mm), are often pale or whitish, and sometimes have a translucent appearance that causes them to disappear when the colon is insufflated with air (Figure 22-4).

FIGURE 22-2. Sessile serrated adenoma/polyp (SSA/P). Note the branching irregular crypts and distorted proliferative zone that characterize this lesion. (Original magnification × 100.) |

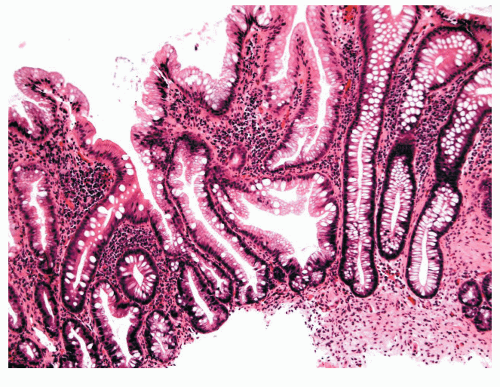

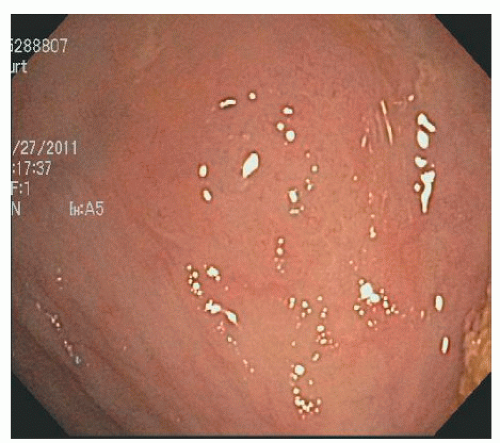

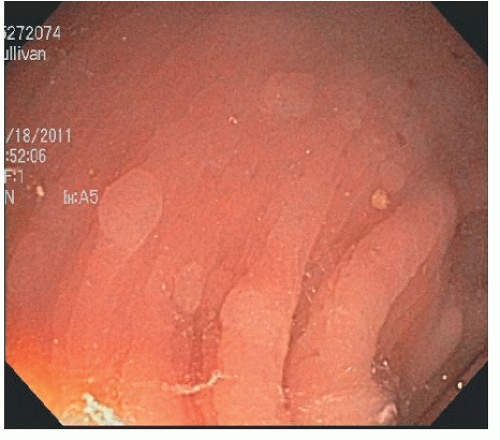

In contrast, SSA/Ps are more commonly located in the right colon. They are less numerous than HPs but are also often associated with synchronous polyps, including other serrated polyps and adenomas. They are often more than 1 cm in diameter and sometimes more than 3 cm. They can be difficult to see because they have an indistinct border and have the same coloring as the surrounding mucosa. They have an innocent crypt pattern that sometimes suggests an edematous fold (Figure 22-5). Many SSA/Ps have a “cap” of tenacious mucus that is characteristic and provides a clue to their presence (Figure 22-6).

TSA is much less common than either HP or SSA/P, being found in less than 1% of colonoscopies. They are generally difficult to pick out endoscopically and, therefore, are usually an unsuspected finding for endoscopists when the pathology report is received. Morphologically, they tend to be more polypoid than SSA/Ps and more discrete.

Evaluation and Management

The approach to serrated lesions of the colon and rectum has changed considerably over the last 10 years. This change has

been caused by a realization that serrated polyps have important implications for cancer risk and prevention. Although some serrated polyps can be diagnosed endoscopically, the accuracy rate is relatively low. Clearly, there is no substitute for accurate histologic assessment. Moreover, there is a lack of uniformity among pathologists in diagnosing the different subtypes of serrated polyps. Because most large right-sided lesions are SSA/Ps, if a large (more than 1 cm) right-sided polyp is reported to be hyperplastic, the slides should be reviewed by a gastrointestinal pathologist and the lesions treated as high risk.115,187,288

been caused by a realization that serrated polyps have important implications for cancer risk and prevention. Although some serrated polyps can be diagnosed endoscopically, the accuracy rate is relatively low. Clearly, there is no substitute for accurate histologic assessment. Moreover, there is a lack of uniformity among pathologists in diagnosing the different subtypes of serrated polyps. Because most large right-sided lesions are SSA/Ps, if a large (more than 1 cm) right-sided polyp is reported to be hyperplastic, the slides should be reviewed by a gastrointestinal pathologist and the lesions treated as high risk.115,187,288

FIGURE 22-4. Hyperplastic (metaplastic) polyp with a translucent appearance. This sort of polyp is prone to disappear on insufflation of the bowel. |

FIGURE 22-5. Sessile serrated adenoma/polyp in the cecum. It is difficult to see and may be ignored as an edematous fold. |

Current approaches to serrated colorectal polyps are based on expert opinion. Small (less than 5 mm), left-sided hyperplastic polyps should be sampled to confirm the diagnosis but need not be completely removed. They may be a marker of risk for proximal adenomas but are unlikely to be dangerous in themselves. Church and colleagues, reporting from the Cleveland Clinic, found that small colonic polyps are usually neoplastic, but even if hyperplastic, they are associated with adenomas elsewhere in 75% of cases.70 Small rectal polyps were usually hyperplastic but still were associated with metachronous neoplasms elsewhere in the colon in 63% of the patients in their report.70 The authors, therefore, recommended total colonoscopy even if only hyperplastic polyps were found at flexible proctosigmoidoscopy. Ansher and associates found that almost one-third of their patients in whom an isolated hyperplastic polyp was found in the left colon harbored a proximal adenomatous polyp.9 They opined that hyperplastic colonic polyps do serve as a marker for adenomatous colonic neoplasms. Conversely, Provenzale and colleagues, in reviewing the records of 1,836 consecutive colonoscopies, found that distal hyperplastic polyps were not strong predictors of the risk for concomitant proximal benign or malignant neoplasms.14 The authors advocated biopsy, however, to confirm the true nature of the lesion. Others also have concluded that small adenomatous and hyperplastic polyps cannot reliably be distinguished by their endoscopic appearance.239

FIGURE 22-6. Sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with a mucus cap in the transverse colon. The cap is an important clue to its presence and its diagnosis. |

Tonooka and coworkers reported a case of carcinoma in a 12-mm hyperplastic polyp in the cecum diagnosed by a magnifying colonoscope.319 When the lesion was seen in the magnified view, an irregularly shaped pit was evident in the center. Biopsy confirmed malignant change at that location.

SSA/Ps are premalignant lesions and should be completely removed. Recent reports describe a high incidence of colon cancer in patients with large serrated polyps and high rates of synchronous and metachronous serrated lesions and advanced adenomas.222 Removal of serrated polyps can be accomplished by snare excision. Although the margins of the polyps can be indistinct and thus predispose to possible recurrence, serrated polyps seem less strongly attached to the underlying mucosa than adenomas and easier to coax into the snare. Polypectomy complication rates are no higher than that for adenomas and may even be lower. Appropriate recognition and detection are as important as resection in their management. Serrated polyps, especially SSA/Ps, can be difficult to see. They are generally the same color as the surrounding mucosa, flatter than adenomas, and with a benign looking crypt pattern that appears like edematous mucosa (see Figure 22-5). The mucus cap is an important clue to their presence, but once this is washed off, the underlying polyp can be almost invisible. The combination of a lack of awareness of the existence of these lesions, the failure to recognize their clinical significance, and an inability to detect them combine to produce a coherent explanation why they pose such a problem in colon cancer screening programs.20 Serrated polyp detection rates, measured in two early studies, reflect these difficulties because of considerable variation between endoscopists.140,178

Surveillance of Patients with Serrated Polyps

Once a patient has a large (more than 1 cm) SSA/P or TSA, he or she is identified as having a high-risk colon. The first aim of surveillance is to make sure that the index lesion is completely removed, and the second aim is to ensure that missed synchronous or rapidly growing metachronous lesions are identified. Therefore, an early follow-up is needed for very large lesions where completeness of excision is in question, with repeat colonoscopy in 6 months. Once a well-healed scar is seen at the site of the polypectomy, and the colon is cleared of any previously missed synchronous lesions,

regular surveillance can start. There are no data upon which to base guidelines, but regimens should be stricter than those that apply to similar sized adenomas, given the increased difficulty in recognizing SSA/Ps. For a single large lesion that was completely removed, a 2-year colonoscopy is reasonable. For several large lesions, a yearly examination is appropriate.

regular surveillance can start. There are no data upon which to base guidelines, but regimens should be stricter than those that apply to similar sized adenomas, given the increased difficulty in recognizing SSA/Ps. For a single large lesion that was completely removed, a 2-year colonoscopy is reasonable. For several large lesions, a yearly examination is appropriate.

Serrated lesions of the colon and rectum are not harmless. Every polyp seen at colonoscopy must be either biopsied or removed, except in cases where there are multiple small hyperplastic polyps in the rectum and sigmoid or in those with polyposis. Colonoscopists must be alert to the possible presence of SSA/Ps and make certain that the right side of every colon is carefully inspected. If a lesion suspicious for SSA/P is seen (mucus cap—see Figure 22-6), it must be completely removed and a sharp lookout maintained for likely synchronous lesions. Such a patient has a high-risk colon, and surveillance must be frequent and meticulous.

Serrated Polyposis Syndrome

Background

Serrated polyposis syndrome (SPS), formerly called hyperplastic polyposis syndrome, is characterized by multiple or large serrated colorectal polyps. Because serrated polyps have been viewed as benign lesions without malignant potential, serrated polyposis has been overlooked as a significant clinical identity. However, increasing understanding of the serrated pathway of colorectal oncogenesis has shed light on this syndrome. In the 1990s, molecular observations demonstrated that some serrated lesions can transform into colorectal adenocarcinoma.44 Before the molecular mechanisms were elucidated, there were multiple reports of colorectal cancer arising in colons affected with multiple hyperplastic polyps. In 2000, Jass described molecular evidence of malignant transformation of serrated polyps via the serrated pathway in a patient with serrated polyposis.166 Recent reports of relatively large case series support an association between serrated polyposis and colorectal cancer,34,37,181 and this is now an accepted entity.

Diagnosis

Although thought to be hereditary, an underlying germ line mutation has not yet been identified. Thus, SPS is a clinical diagnosis based on criteria defined by the WHO initially in 200045 and revised in 2010.303 Diagnostic criteria include (1) at least five serrated polyps proximal to the sigmoid colon with two or more of these being more than 10 mm, (2) any number of serrated polyps proximal to the sigmoid colon in an individual who has a first-degree relative with serrated polyposis, or (3) more than 20 serrated polyps of any size, but distributed throughout the colon.303 For a definition of SPS, any of the serrated polyps (HP, SSA/P, TSA) qualify, and polyp counts may be cumulative.143 The newer nomenclature has been adopted in recognition of the fact that many of the serrated polyps in this syndrome are actually sessile serrated polyps/adenomas rather than solely traditional hyperplastic polyps.

Clinical Presentation

As implied by the varied definitions, SPS is a phenotypically diverse disease. These broad and diverse criteria make it difficult to summarize specific patient characteristics of the condition, and different SPS phenotypes have been suggested. Some patients have multiple small polyps throughout the colon (Figure 22-7), whereas others have a few large, rightsided polyps181 as demonstrated in Figure 22-8. In addition to serrated polyps, the majority of patients with SPS also harbor adenomas.34,48,58,181

FIGURE 22-7. Multiple small hyperplastic polyps in the left colon in a patient with serrated polyposis syndrome. |

Serrated polyposis mainly affects individuals with white European ancestry; this population accounts for approximately 95% of cases.37,181,353 It affects both genders and has been diagnosed across age groups. Larger series report an equal gender distribution or a slight male predominance,34,48,181 but one series notes a majority (55%) being women.58 Median age at diagnosis ranges from 44 to 62 years, with extremes of age including SPS in a 10-year-old and a man in his 80s.34,48,58,181 SPS is usually asymptomatic, but bleeding may arise from colorectal cancer or from large polyps.

Association with Malignancy

Based on multiple case series, the incidence of colorectal cancer in SPS is approximately 25% to 50%, although the precise risk is still uncertain.48,58,101,151,181,197,201,271,281,353 The natural history is not well defined because the initial diagnosis is often made when a cancer is detected.34,181 In a retrospective study reporting on 77 SPS patients who were followed for a mean of 5.6 years, 27 (35%) developed colorectal cancer—22 at initial endoscopy and 5 during follow-up. The cumulative risk of colorectal cancer was calculated to be 7% at 5 years while under a surveillance program.34 Cancer risk seems to be similar regardless of the polyp phenotype.181 The true incidence of colorectal cancer risk will only be determined when the disease is defined genetically, and longitudinal long-term observational studies are conducted.

Colorectal cancers seem to be more prevalent within SPS families because approximately 40% to 50% of patients have a family history of colorectal cancer.58,181 A recent study noted a relative risk of 5.4 for the incidence of colorectal cancer in first-degree relatives of those with SPS compared with the general population.34 These numbers may be overestimates because the data are likely to be affected by ascertainment bias, with patients having a family history more likely to be recognized and pursued in the clinics.

Clinical Management

Surveillance and Colonoscopy

The goal of colorectal surveillance in SPS is to prevent colorectal cancer by detection and removal of premalignant lesions. Management guidelines are based on clinical experience and expert opinion and continue to evolve.237,181,303 For those with an established clinical diagnosis, suggested protocols include colonoscopy every 1 to 2 years. The interval to subsequent colonoscopy depends on the number and histologic characteristics of the polyps. All single polyps larger than 5 mm should be removed and examined histologically. For clusters of small (3 to 4 mm) left-sided polyps, which are likely benign hyperplastic polyps, representative biopsies should be performed. The interval to the next examination may be extended to 2 to 3 years if the colon remains clear of polyps on successive annual colonoscopies, but this should be considered on a case-by-case basis. Surgical consultation is necessary when endoscopic management cannot control the polyp burden, if histologic high-grade dysplasia is found, or if patients are not compliant with the surveillance regimen.

Because there is a suggested increased risk of colorectal cancer in first-degree relatives of patients with SPS, colonoscopy screening should be offered to first-degree relatives, particularly those older than 40 years. Endoscopic findings and polyp histology should guide the interval to the next colonoscopy. Patients with a normal colonoscopy may reasonably be evaluated every 5 years. Prospective longitudinal studies with regular surveillance protocols for SPS patients and first-degree relatives are necessary in order to determine the true natural history of the disease and to guide clinical management.

Surgical Management

Indications for surgery include the inability to adequately control the polyp burden endoscopically, uncontrolled symptoms such as bleeding, and the development of colorectal cancer. The risk of neoplasia affects the entire colorectum, and so subtotal or total colectomy should be considered. This should be determined on an individual basis considering medical comorbidities and anal sphincter function. For patients who cannot tolerate an extended surgery or who have focal disease (e.g., a few large right-sided polyps), a segmental colectomy may be performed. Regardless of surgical treatment, the remaining colorectum should be surveyed endoscopically every year. There are no prospective studies evaluating this management plan. It is simply based on our opinion.

▶ HAMARTOMAS

A hamartoma is defined as a nonneoplastic growth that is composed of an abnormal mixture of tissue normally found at the site. In the colon, this includes juvenile and Peutz-Jeghers polyps.

Juvenile Polyps

The solitary juvenile polyp (congenital polyp, retention polyp, juvenile adenoma) is usually found in children younger than 10 years of age, but it is also seen in older children and in adults at any age.227 It is an uncommon condition, occurring in approximately 1% of asymptomatic children.108 The age distribution has been reported to have a bimodal pattern.280 According to Roth and Helwig, the childhood group has a modal age of 4 years, whereas the adult group has a modal age of 18 years. The incidence is twice as frequent in boys, and there is a 13:1 ratio of men to women in adults.280

Although juvenile polyps are the most common colorectal tumor in children, benign and malignant neoplasms can present at virtually any age.24,195 Billingham and colleagues observed that solitary adenomas accounted for 7.4% of all polyps found in patients younger than 20 years of age.29

Appearance

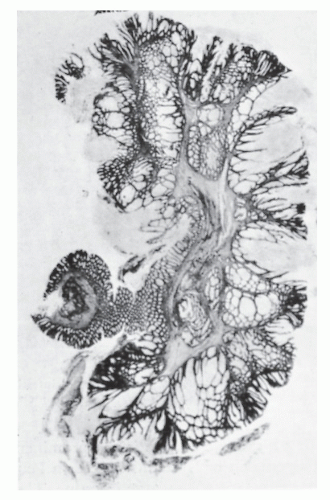

Juvenile polyps are usually round or oval, with a smooth, continuous surface, in contrast to the papillary surface that characterizes the adenomatous polyp.194 They are usually pedunculated, and in juvenile polyposis, the stalks can be long with secondary polyps developing like branches on a tree. Juvenile polyps are characteristically cherry red. Their cut surface demonstrates numerous cystic spaces filled with mucus (Figure 22-9).

Histology

Microscopic examination reveals that juvenile polyps are due to an overgrowth of the lamina propria. They are composed of an epithelial and a connective tissue element, with the latter contributing the bulk of the tumor mass (Figure 22-10).176 Mucin-filled spaces are characteristic, and acute and chronic inflammatory cells are frequently seen. This may lead to their being labeled as “inflammatory polyps,” a label that can lead to a delay in diagnosis.

Etiology

Alexander and colleagues noted that a frequent microscopic finding is infiltration by eosinophils.5 They postulated that because eosinophils usually connote an allergic response, the polyps are the result of allergy. In support of this theory is the observation that there was a statistically significant increased incidence of allergy in children with polyps and in the families of those children. Despite the suggestion by some that juvenile polyps may be neoplastic, most pathologists today agree with Morson that the lesion is a hamartoma.227 Morson based his conclusion on the observations that there is an abnormality of the mucosal connective tissue or lamina propria and that this connective tissue stroma bears a resemblance to primitive mesenchyme. This concept lends support to the contention that the lesion is a malformation rather than a neoplasm. One theory proposes that the polyp is a form of retention cyst that takes on a polypoid form from traction as a result of peristalsis.

Symptoms and Signs

The most common presenting complaint is rectal bleeding, followed by prolapse or protrusion of the mass, passing of tissue, and abdominal pain. Autoamputation is noted in up to 10% of patients. Diarrhea, mucus, proctalgia, tenesmus, and rectal prolapse have also been reported, although are unlikely to happen with solitary polyps and are symptoms more typical of juvenile polyposis.

Distribution

Mazier and associates reported 258 patients with juvenile polyps.219 Sixty percent of the polyps were located within 10 cm of the anal verge. Only 10% were located farther away than 20 cm, but these were scattered throughout the colon. Approximately 75% were greater than 1 cm in diameter. Jalihal and colleagues found that 80% of the more than 100 colonoscopic polypectomies performed for juvenile polyps were in the rectosigmoid region.160

JOHANNES LAURENTIUS AUGUSTINUS PEUTZ (1886-1957)

|

Johannes Peutz was born in Holland and educated at Rolduc, where he began the study of medicine in 1905. After qualification in 1914, Peutz trained in internal medicine at the Coolsingel Hospital in Rotterdam, as well as at clinics in Germany, Italy, and Belgium. In 1917, he became principal physician to the hospital of St. Joannes de Deo, a Roman Catholic hospital at the Hague, where he remained for 34 years until his retirement in 1951. He is credited with the establishment of an independent department of internal medicine and a laboratory with electrocardiographic facilities built to his specifications. Peutz was a dedicated clinician and a keen observer, with broad scientific and humanitarian interests. In 1921, he was conferred the degree of doctor of medicine for his thesis involving the diagnosis and treatment of disorders of the pancreas. In recognition of his many contributions, Peutz was awarded the Pro Ecclesia et Pontifice Medal, the Order of St. Gregorius the Great, and the Order of Orange-Nassau. (Courtesy of Faisal Aziz. Photograph courtesy of Udo Rudloff, MD.)

Diagnosis and Management

Diagnosis is usually made at proctosigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy, and the lesion should be removed. Full colonoscopy is performed to exclude the possibility of juvenile polyposis. Five or more synchronous juvenile polyps, or a family history of juvenile polyposis in a patient with one polyp, are enough to make the diagnosis.167 One solitary juvenile polyp, itself, is neither a neoplasm nor a premalignant condition. Once the polyp is removed, no further follow-up is required.184,243

Peutz-Jeghers Polyps

In 1921, Peutz reported a familial syndrome of polyps of the gastrointestinal tract with pigmentation of the mouth and other parts of the body.261 Later, Jeghers and his colleagues established the syndrome by describing a number of cases.169 The disease appears to be transmitted in an autosomal dominant fashion, but de novo cases have been reported without any suggestive family history.

Pathology of Peutz-Jeghers Polyps

Although hamartomas, Peutz-Jeghers polyps are histologically distinct from juvenile polyps. The main difference is that they are due to an overgrowth of the muscularis mucosae, rather than the lamina propria. The arborizing muscle of

the muscularis mucosae makes a longitudinal polyp section look like a tree. There is less mucin and less inflammatory infiltrate than found with juvenile polyps. As with juvenile polyps, solitary Peutz-Jeghers polyps are occasionally found during routine colonoscopy. In the absence of a family history of Peutz-Jeghers polyposis or any of the other phenotypic characteristics of this syndrome, solitary Peutz-Jeghers polyps carry no increased risk of cancer and no surveillance is required.249

the muscularis mucosae makes a longitudinal polyp section look like a tree. There is less mucin and less inflammatory infiltrate than found with juvenile polyps. As with juvenile polyps, solitary Peutz-Jeghers polyps are occasionally found during routine colonoscopy. In the absence of a family history of Peutz-Jeghers polyposis or any of the other phenotypic characteristics of this syndrome, solitary Peutz-Jeghers polyps carry no increased risk of cancer and no surveillance is required.249

HAROLD JOSEPH JEGHERS (1904-1990)

|

Harold Jeghers was born September 26, 1904. He received his bachelor of science degree in 1928 from the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York and then attended the Case Western Reserve University Medical School in Cleveland, Ohio, graduating in 1932. There followed training in internal medicine at the Evans Memorial Institute for Clinical Research in Boston and at the Boston City Hospital. He then became consultant physician to the Boston City Hospital, where he held a teaching post from 1937 to 1946. In 1946, he was appointed professor of medicine and physician-in-chief at Georgetown University School of Medicine in Washington, DC while also serving as consultant to the Walter Reed Army Medical Center and the National Naval Hospital. Jeghers returned to Boston as professor of medicine at Tufts University Medical School in 1966 and retired in 1974. Jeghers was active as a visiting lecturer at a large number of American institutions and English universities. In 1935, Jeghers began building a medical library based on his own method of indexing, which today is known as the Jeghers Medical Index System. (With appreciation to Faisal Aziz.)

Hamartomatous Polyposis Syndromes

The hereditary hamartomatous polyposis syndromes are represented by a variety of rare autosomal dominant conditions characterized by the presence of gastrointestinal hamartomatous polyps. The various diseases include juvenile polyposis syndrome (JPS), Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS), and the PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome (PHTS) of which Cowden syndrome and Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome (BRRS) are subsets. Each of the hamartomatous syndromes has a unique clinical picture and associated cancer risks. Taken together, hamartomatous polyposis syndromes are responsible for less than 1% of cases of colon cancer in North America.235

Juvenile Polyposis Syndrome

JPS occurs in approximately 1 in 100,000 individuals43 and is characterized by the development of multiple juvenile polyps throughout the gastrointestinal tract. The term “juvenile” is indicative of the type of polyp rather than to the age of onset. Histologically, juvenile polyps are characterized by a normal epithelial component and an abundant lamina propria, but lack smooth muscle. Approximately 2% of children and adolescents will have a solitary juvenile polyp. This manifestation does not carry an increased risk of malignancy and is distinct from JPS.

Genetics

JPS is an autosomal dominantly inherited disease. Approximately 60% of cases of JPS are considered familial, whereas the remaining 40% are believed to occur sporadically.290 Germ line alterations in three genes—BMPR1A, SMAD4, and ENG1—are associated with JPS. SMAD4 is a tumor suppressor gene in the transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) signal transduction pathway, and approximately 20% of patients will have detectable SMAD4 mutations.148 BMPR1A is a type I receptor of the TGF-β superfamily that regulates BMP intracellular signaling through SMAD4. Gene sequence analysis will identify BMPR1A mutations in 20% of cases,148 and an additional 4% will be detected by analysis of large deletions in BMPR1A.12,330 Patients with JPS may also have mutations in ENG1.312

Diagnosis

JPS remains a clinical diagnosis made by endoscopy with confirmation of a germ line mutation in approximately 50% of cases. Clinical criteria for a JPS diagnosis include the following: (1) more than five juvenile polyps of the colon or rectum, (2) juvenile polyps in the extracolonic gastrointestinal tract, or (3) any number of juvenile polyps and a positive family history.167 Patients who satisfy any of these criteria should be offered genetic counseling and genetic testing. After identification of a specific mutation, at-risk family members should also be tested for that mutation. Approximately 75% of patients will have an affected parent, and if the mutation is detected in such an individual, testing should be offered to siblings of the proband because they have a 50% chance of also being affected. Offspring of the proband also have a 50% chance of inheriting the mutation and should be tested accordingly. After appropriate genetic counseling, at-risk family members should be tested in their teenage years.

Clinical Presentation

Gastrointestinal juvenile polyps are the cornerstone of this disease with variable expression leading to different severity of disease. Polyps occur throughout the gastrointestinal tract, including the colon and rectum, stomach, and small bowel. The majority of patients develop polyps by their teen years, with the polyp burden varying from a few to hundreds. Symptoms are related to the polyps and most commonly include acute or chronic gastrointestinal bleeding, iron-deficiency anemia, prolapsed rectal polyps, abdominal pain, or diarrhea. Hypoproteinemia, hypokalemia, anergy, finger clubbing, and a failure to thrive may also be seen.88,221 Extracolonic congenital and acquired manifestations have also been associated with JPS, including abnormalities of the heart and cranium, double renal pelvis and ureter, cleft palate, polydactyly, and malrotation of the gut.88,167

Recently, JPS has been linked to hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) via a mutation in SMAD4. HHT is an autosomal dominant condition that is characterized by skin

and mucosal telangiectasias; cerebral, pulmonary, and hepatic arteriovenous malformations; and an increased risk of associated hemorrhage. JPS patients with an SMAD4 mutation are also at risk for the visceral manifestations of HHT, and any HHT patient with SMAD4 mutation is at risk for early onset gastrointestinal cancer.105,156

and mucosal telangiectasias; cerebral, pulmonary, and hepatic arteriovenous malformations; and an increased risk of associated hemorrhage. JPS patients with an SMAD4 mutation are also at risk for the visceral manifestations of HHT, and any HHT patient with SMAD4 mutation is at risk for early onset gastrointestinal cancer.105,156

Association with Malignancy

Patients with JPS have approximately a 50% lifetime risk of developing colorectal cancer with a wide range between 17% and 68%.1,147,164 Colorectal cancer is diagnosed at a mean age of 43 years,36 but there is a report of cancer developing in a 15-year-old.167 Cancers also may develop in the stomach, duodenum, pancreas, and jejunum. The risk of gastric or duodenal cancer is 15% to 21%.147,291 Neoplastic degeneration is more likely to occur in patients with the generalized form of polyposis compared with those who have colorectal polyposis only.1

Clinical Management

Surveillance

Colonoscopic surveillance for patients with JPS is recommended to begin at age 15 or earlier if symptoms develop.47,237 Colonoscopy is preferred to that of flexible sigmoidoscopy because the right colon is also prone to developing polyps and cancer. If the examination reveals no polyps, repeat colonoscopy is recommended in 2 to 3 years. If any polyps are found, they should be removed endoscopically and sent for pathologic examination. When polyps are detected and removed, repeat examinations should be performed annually until the colon is free of polyps. At this time, the screening interval may revert to every 2 to 3 years. Colectomy is recommended if the polyp burden cannot be managed endoscopically or if high-grade dysplasia is seen. Upper gastrointestinal surveillance is recommended to begin between ages 15 and 25 or earlier if symptoms develop. Endoscopic management principles follow those as given for adenomas, although juvenile polyps are almost always pedunculated and tend to have longer stalks.

Surgery

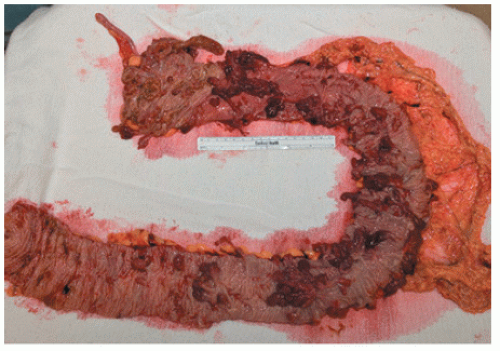

Surgery is an important part of treating JPS patients. Despite a known significant cancer risk, there is no evidence that prophylactic colectomy reduces cancer development when compared with colonoscopy with polypectomy. Prophylactic colectomy may be considered for patients with significant symptoms, those whose polyp burden cannot be managed endoscopically, those whose family history includes colorectal cancer, and for those with poor compliance. A colectomy is also warranted when a patient develops dysplasia in the polyps. A resected colon with diffusely distributed juvenile polyps is shown in Figure 22-11.

Surgical options for colonic disease include colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis, subtotal colectomy with ileosigmoid anastomosis, or total proctocolectomy. The authors prefer to leave the rectum in place and perform total abdominal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis unless there is cancer in the rectum or if symptoms are being caused by rectal disease. This operation avoids the potential complications of pelvic surgery and yields better bowel function, an issue that is particularly important for younger patients. In a retrospective study from the Cleveland Clinic, 10 patients with JPS underwent colectomy with preservation of the rectum.248 Five of these individuals eventually required a proctectomy at a median time of 9 years (range, 6 to 34 years). It is also important to note continued surveillance is still required regardless of the surgery performed because polyps may develop in the remaining rectum or ileal pouch.248

Cancer risk is lower in the upper gastrointestinal tract compared to the colon, and the need for surgery is determined by symptoms, development of malignant change, or the presence of protein-losing gastropathy/enteropathy. Subtotal gastrectomy is usually the procedure of choice for disease in the stomach, and segmental resection is performed for small bowel disease.

Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome

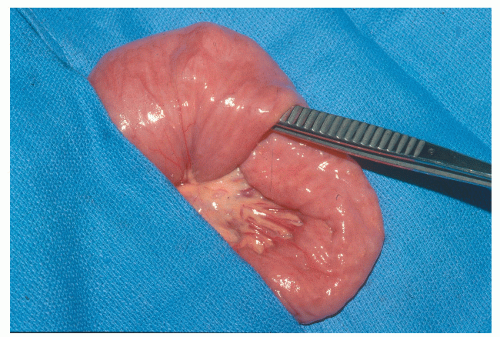

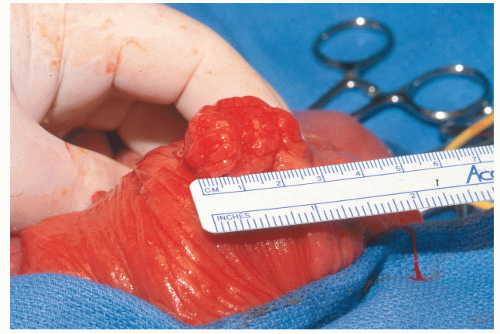

PJS was first reported in 1895 as a familial syndrome of gastrointestinal polyps with characteristic pigmentation of the mouth and other parts of the body.261 It was not recognized as a distinct entity until 1949 when Jeghers reported two additional cases.170 PJS occurs in approximately 1 in 25,000 to 1 in 280,000 people. Peutz-Jeghers polyps have a characteristic frond-like branching structure, with smooth muscle proliferation and appropriate epithelium of the gastrointestinal tract (Figure 22-12).

Genetics

PJS is autosomal dominantly inherited, and germ line mutations in STK11 are the underlying cause.138 It is believed that a somatic loss of the second allele results in manifestations of the disease. Gene sequence analysis uncovers approximately 40% to 70% of mutations.8,11,334

Diagnosis

PJS is a clinical diagnosis based on meeting one of the following WHO criteria: (1) three or more histologically confirmed Peutz-Jeghers polyps; (2) any number of Peutz-Jeghers polyps with a family history of PJS; (3) characteristic, prominent, mucocutaneous pigmentation with a family history of PJS; or (4) any number of Peutz-Jeghers polyps and characteristic prominent, mucocutaneous pigmentation.112

Genetic counseling should be offered to any patient meeting the aforementioned criteria. After identification of a specific mutation, at-risk family members can be tested for this family-specific mutation. Approximately half of cases will have an affected parent, and parents should be carefully evaluated for features of PJS. If one of the parents is affected, then testing should be offered to the siblings of

the proband. Additionally, all children of the proband have a 50% risk of inheriting the mutation and should be tested accordingly. Genetic testing for at-risk family members may be performed at age 8 after appropriate genetic counseling and informed consent.113

the proband. Additionally, all children of the proband have a 50% risk of inheriting the mutation and should be tested accordingly. Genetic testing for at-risk family members may be performed at age 8 after appropriate genetic counseling and informed consent.113

Clinical Presentation

Gastrointestinal hamartomatous polyps coupled with the unique, distinctive mucocutaneous pigmentation are the key features of PJS. The classic PJS pigmentation is seen in approximately 95% of cases and most commonly detected on the vermillion border of the lips (94%), buccal mucosa (66%), hands (74%), and feet (62%), but has also been reported in the periorbital, perianal, and genital areas.112,355 The usual appearance is that of small, dark brown or blue-brown macules in infancy, which may fade in late adolescence.

Approximately 88% of patients with PJS will develop hamartomatous polyps,324 with the small bowel as the most common site, followed by colon, stomach, and rectum. Polyps vary in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters, and with increasing size, they tend to become pedunculated. Most patients will have fewer than 20 polyps, but these will often cause symptoms such as obstruction, abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding, polyp prolapse per anus, or recurrent small bowel intussusception (Figures 22-13 and 22-14).324 Symptoms usually develop by the second or third decade of life. Rare cases of polyps developing in the renal pelvis, urinary bladder, lungs, and nares have been reported.

Association with Malignancy

Patients with PJS have an increased risk of developing various malignancies. A meta-analysis of 210 patients reported a 93% estimated lifetime risk of developing cancer.109 The risk for developing breast, colon, pancreatic, and gastric cancer is 54%, 39%, 36%, and 29%, respectively. Cancers in the reproductive organs have also been rarely associated with PJS. Men are at risk for testicular tumors of sex cord and Sertoli cell type, and women are at risk for the development of sex cord tumors with annular tubules of the ovary and adenoma malignum of the cervix.

Clinical Management

Surveillance and Endoscopic Intervention

Regular surveillance of multiple organs is necessary for PJS patients. Randomized controlled trials have not been performed to evaluate the efficacy of cancer surveillance protocols, and published recommendations are based on expert opinion. Specific testing depends on the patient’s age and gender. For patients with a diagnosis of PJS, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends screening starting at age 8 to 10 years, with evaluation of the small bowel. The interval to the next examination is based on the findings of that exam. If it is normal, repeat evaluation is recommended at age 18 at the latest, then at 2 to 3 years

intervals.237 Males should undergo annual testicular physical examination starting at age 10 years, and females should undergo annual pelvic examination and Papanicolaou stain starting at age 18 to 20 years. Women should also have breast physical examinations every 6 months and annual mammogram and breast MRI starting at age 25 years. Both genders should undergo colonoscopy and upper endoscopy beginning in their late teens and repeated every 2 to 3 years based on findings. To detect early pancreatic cancer, endoscopic ultrasound or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) along with serum CA19-9 every 1 to 2 years starting at age 25 to 30 years is recommended. Other screening regimens have been proposed by other authors.46,113,355

intervals.237 Males should undergo annual testicular physical examination starting at age 10 years, and females should undergo annual pelvic examination and Papanicolaou stain starting at age 18 to 20 years. Women should also have breast physical examinations every 6 months and annual mammogram and breast MRI starting at age 25 years. Both genders should undergo colonoscopy and upper endoscopy beginning in their late teens and repeated every 2 to 3 years based on findings. To detect early pancreatic cancer, endoscopic ultrasound or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) along with serum CA19-9 every 1 to 2 years starting at age 25 to 30 years is recommended. Other screening regimens have been proposed by other authors.46,113,355

Evaluation of small bowel polyposis is technically difficult because much of the small bowel is not easily evaluated by endoscopy. Capsule endoscopy and double-balloon enteroscopy are more commonly being used to identify jejunal and ileal polyps.42,57,193 However, the true impact that these tests have on surveillance and treatment remains inadequately defined.

Endoscopic management of PJS can be considered both prophylactic, as in polypectomy on asymptomatic polyps found during surveillance, and treatment of polyp-related complications. Similar to the surveillance guidelines, intervention recommendations are from expert opinion rather than through controlled studies. Asymptomatic gastric or colonic polyps larger than 1 cm should be removed endoscopically. For small bowel polyps, those larger than 1 to 1.5 cm or those that are rapidly growing (based on prior examinations) should be removed to decrease future complications. The most common complications are bleeding and intussusception. For slowly bleeding polyps causing anemia, endoscopic resection is the first option. However, polyps may be located beyond the reach of conventional endoscopic techniques. An endoscopic approach combined with laparoscopy or laparotomy, which allows the surgeon to guide the endoscope, may be employed to reach the lesion of interest.306,326

Surgery

Obstruction and bleeding are the most common indications for surgical intervention. Although most intussusceptions resolve spontaneously, if the obstruction does not resolve in a few hours, surgery is required. The affected area should be resected with sparing as much bowel as possible because there will likely be future surgery, and resection may be needed. Removing all polyps at the time of surgery to achieve a “clean sweep” is advocated to reduced the need for future operations.250 The search for polyps may be accomplished through the open resection ends of the bowel or via an enterotomy. An operative endoscopy by means of an enterotomy (intraoperative enteroscopy) can also facilitate this search. Edwards used this method on 25 patients and identified 350 polyps not detectable by palpation or transillumination.92

PTEN Hamartoma Tumor Syndrome

The term PHTS was introduced to group the clinically described syndromes that are caused by germ line PTEN mutations.215,216 Both Cowden syndrome and BRRS are characterized by colonic hamartomatous polyps and are caused by mutation in the PTEN gene. Cowden syndrome was first recognized in 1962 and was named for the patient who had the disease.208 In 1971, Bannayan reported the first case of what later became known as BRRS.17 Despite the seemingly distinct presentations distinguishing each of these hamartomatous polyposis syndromes, making the correct diagnosis for these conditions can be challenging because significant overlap exists.

Genetics

Cowden syndrome and BRRS are both autosomally dominant inherited disorders. Germ line mutations in PTEN were identified in patients and families with Cowden syndrome in 1996203,215 and also in patients with BRRS in 1997.217 PTEN is a tumor suppressor gene that encodes a phosphatase, which is involved in the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. It plays a key role in apoptosis. Approximately 80% of patients who meet the diagnostic criteria for Cowden syndrome and 60% of patients with BRRS have PTEN mutations.215,216

Diagnosis and Clinical Presentation

A PHTS diagnosis can be considered based on clinical findings, but definitive diagnosis is made by identification of a germ line PTEN mutation. The International Cowden

Consortium has proposed operational clinical diagnostic criteria for Cowden syndrome, including both major and minor criteria.127,355 Major criteria include breast cancer, thyroid cancer (especially follicular), macrocephaly, endometrial cancer, and Lhermitte-Duclos disease. Minor features include benign thyroid changes (such as a goiter), mental retardation, hamartomatous intestinal polyps, fibrocystic changes in the breast, lipomas, fibromas, genitourinary tumors (such as kidney cancer or uterine fibroids), or malformations. Cowden’s syndrome is diagnosed if a patient has either macrocephaly or Lhermitte-Duclos disease and one other major feature. A diagnosis of Cowden is also made when a person has one major feature and three minor features, or at least four minor features.

Consortium has proposed operational clinical diagnostic criteria for Cowden syndrome, including both major and minor criteria.127,355 Major criteria include breast cancer, thyroid cancer (especially follicular), macrocephaly, endometrial cancer, and Lhermitte-Duclos disease. Minor features include benign thyroid changes (such as a goiter), mental retardation, hamartomatous intestinal polyps, fibrocystic changes in the breast, lipomas, fibromas, genitourinary tumors (such as kidney cancer or uterine fibroids), or malformations. Cowden’s syndrome is diagnosed if a patient has either macrocephaly or Lhermitte-Duclos disease and one other major feature. A diagnosis of Cowden is also made when a person has one major feature and three minor features, or at least four minor features.

Consensus diagnostic criteria for BRRS are not established, but a diagnosis should be considered in patients with the key features of macrocephaly, hamartomatous colonic polyposis, lipomas, and pigmented macules of the glans penis.118 Approximately half of the patients with BRRS will have hamartomatous polyps in the digestive tract, particularly in the ileum and colon.118 These can cause intussusception and rectal bleeding but are not believed to increase the risk of colon cancer.

Association with Malignancy

PHTS syndromes carry mainly a risk of extracolonic cancers. Women have a 50% lifetime risk of developing breast cancer and a 5% to 10% lifetime risk of developing endometrial cancer. Men and women with Cowden syndrome have a 10% lifetime risk of developing epithelial thyroid cancer. Hamartomatous polyps have been reported in patients with Cowden syndrome, although they have not yet been recognized as a major or minor component of the condition. One recent report identified colorectal cancer in 13% of PTENmutation carriers. All cancers occurred before the age of 50 years. The adjusted standardized incidence ratio was 224 (95% confidence interval [CI], 109.3-411.3; P < .0001).135 This is the first report of an association with Cowden syndrome and colorectal cancer.

Patients with BRRS by virtue of a PTEN mutation carry similar extracolonic malignancy risks as those with Cowden syndrome. Approximately half of the patients with BRRS will have hamartomatous polyps in the digestive tract, particularly in the ileum and colon.118 These polyps can become symptomatic but are not believed to increase the risk of colon cancer.

Surveillance and Clinical Management

There are no specific recommendations for colon cancer or polyposis surveillance because data are limited about the true prevalence of colon cancer in Cowden syndrome. A Cleveland Clinic study reported an adjusted standardized incidence ratio for colorectal cancer of 224 (95% CI, 109.3-411.3; P < .0001). All cancers occurred before the age of 50. The authors of that study recommended baseline colonoscopy at age 35 for patients with Cowden syndrome, with subsequent follow-up dependent on the polyp burden but no less frequent than every 5 years. This is a fairly new conclusion, and the recommendation has not been adopted into any published professional guidelines.135 In BRRS, although there is not believed to be a cancer risk, the colorectal polyp burden may be significant and cause symptoms such as bleeding or obstruction. Treatment is based on symptoms. Extracolonic cancer surveillance focuses on more prevalent cancers, such as breast, thyroid, and endometrium.237

Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome

In 1955, Cronkhite and Canada described a nonfamilial syndrome of gastrointestinal polyposis, hyperpigmentation, alopecia, and nail dystrophy.81 The syndrome is thought to be a variant of juvenile polyposis with ectodermal changes, but this is not believed to be an inherited or genetically transmitted disease.270 Gastrointestinal polyps are found in 52% to 96% of patients and may be located along the alimentary tract from the stomach to the rectum.83 These are hamartomatous polyps with similar histology to that of juvenile polyps, but the intervening mucosa between polyps is histologically abnormal, characterized by inflammation and edema. These polyps may contain adenomatous changes. The finding of dysplasia in a polyp should encourage the endoscopist to pursue an aggressive surveillance program. The polyps may be seen in association with neoplasms of the colon and are considered by some authors to represent a premalignant condition.214,270

Presentation

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome usually presents as an acute illness with rapid progress of protein-losing enteropathy and unique extraintestinal manifestions. Anemia and rectal bleeding are commonly reported.83 The mean age at diagnosis is 62 years. Morbidity is caused by the physiologic effects of severe diarrhea, weight loss, and complications of malnutrition.83

Association with Malignancy

The risk of colorectal cancer is approximately 9%, and the risk of colorectal adenomas or adenomatous change is 40%.46 Because there is also an increased risk of gastric cancer in this syndrome, screening of the colon and stomach should be considered.

Management

Overall prognosis is poor because there is no effective specific treatment. Most patients have been treated symptomatically by means of nutritional support.100 If possible, enteral feeding is preferred, but it is more likely that parenteral feeding will be necessary with supplemental calories, nitrogen, and lipids, in addition to appropriate fluids, electrolytes, and vitamins. Symptomatic remission occasionally may occur with supportive care. Glucocorticoids, anabolic steroids, antibiotics, and surgical resections have been successful in some patients, but the variety of approaches makes it difficult to identify the most effective intervention. Surgical therapy is risky in these malnourished patients and, therefore, has a limited role. Resection is indicated when involvement is confined to a segment amenable to excision, whether it be stomach, small bowel, or colon.78 The causes of death are subsequent to the disease complications, such as cachexia, malnutrition, septicemia, and shock.83 Specific management awaits a better understanding of this perplexing syndrome.

Hereditary Mixed Polyposis Syndrome

Hereditary mixed polyposis syndrome was described in 1997 in a family with a number of polyps with different histology, including atypical juvenile polyps, hyperplastic polyps, adenomas, and even carcinoma.346 This disease follows autosomal dominant inheritance. Linkage to chromosome 15q14-q22 in a region of a potential colonic cancer gene, CRAC1, has been reported.158,317 This is a rare disease, but

the usual presentation includes less than 15 colonic polyps at presentation. There are no extracolonic manifestations. The median age of onset of symptoms is 40 years. The mean age of colorectal cancer diagnosis is 47 years, and the risk is believed to increase compared with the general population. Surveillance colonoscopy has been recommended every 1 to 2 years for patients with this disease.46

the usual presentation includes less than 15 colonic polyps at presentation. There are no extracolonic manifestations. The median age of onset of symptoms is 40 years. The mean age of colorectal cancer diagnosis is 47 years, and the risk is believed to increase compared with the general population. Surveillance colonoscopy has been recommended every 1 to 2 years for patients with this disease.46

▶ ADENOMAS

Polyps in the large bowel keep bad company.

—RUPERT B. TURNBULL

An adenoma is a benign neoplasm of glandular origin and the most common neoplasm of the colon and rectum. Adenocarcinoma, the most common cancer of the colon and rectum and the third most common cancer of solid organs in the human body, arises from an adenoma. Thus, adenomas are significant because they are cancers “in the making.” Although only 1 in every 100 to 200 adenomas will ever become malignant, all adenocarcinomas of the large bowel arise in dysplastic epithelium. Their significance lies in the fact that we have access to these precursor lesions containing dysplasia via colonoscopy and the opportunity to prevent cancer by removing them.

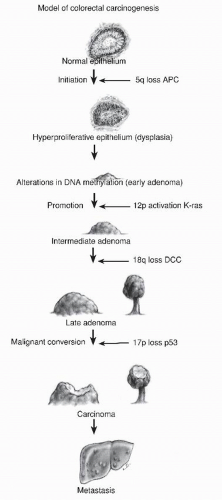

Genetic Basis of Adenomas

A common question asked by patients is “Why did I get these polyps?” A simple answer is “It’s in your genes.” All colorectal neoplasia is genetic, the result of an accumulation of genetic abnormalities in the colorectal mucosa that begins in early childhood and progresses throughout life. These genetic abnormalities predispose to loss of function in key pathways controlling cell growth, differentiation, and death. In 1988, Vogelstein proposed a sequence of genetic abnormalities that could be associated with progressively higher risk adenomas, providing a genetic mechanism for a polyp-cancer sequence (Figure 22-15).332 It may seem that this observation had been well established, but it has been less than 40 years since the validity of the polyp-cancer sequence has been generally accepted. It was in 1939 that Swinton and Warren published their seminal article on the subject, and then it was roundly criticized.313 At the time, most physicians believed cancers of the colon arose de novo, in otherwise normal bowel.

Since then, the “Vogelgram” has been confirmed and labeled as a chromosomal instability mechanism for the development of colorectal cancer. It involves early loss of APC, setting the stage for multiple chromosomal abnormalities that in turn cause loss of gene expression by loss of heterozygosity. Global hypomethylation causes an overall instability of DNA expression. Mutations in SMAD4 and P53 are later events as larger adenomas become cancers.332 Sanchez and associates showed that this mechanism causes 70% of colorectal cancers,287 whereas Kalady and colleagues refined its role, describing participation in 90% of rectal cancer and approximately 60% of colon cancers.182 There are two other main genetic mechanisms by which colorectal cancer develops. The mutator mechanism is caused by deficient DNA mismatch repair. When this is due to an inherited mutation in a mismatch repair gene (Lynch syndrome), the precursor lesion to cancer is an adenoma.31 Some of these mutator adenomas are microsatellite unstable, with the proportion depending on size. Sporadic mutator cancers due to promoter methylation of the mismatch repair gene MLH1 have serrated polyps as precursor lesions.51,166,255,320

Epidemiology

The fact that all colorectal neoplasia is genetic begs the question as to what causes the genetic abnormalities that lead to polyps and cancer. The answer to this is undoubtedly multifactorial, but Lichtenstein in a study of 4,000 sets of Scandinavian twins was able to conclude that 65% of all colorectal cancer is from environmental influences, whereas 35% has some hereditary component.204 The environmental influences

include diet, lifestyle, and exposure to other carcinogens such as nicotine. Dietary factors associated with a predisposition to cancer include red meat, animal fats, and alcohol, whereas fresh fruit and fiber have a protective effect.4,186,269,295 Estrogen is a protective factor as shown by the reduced rate of polyps and cancer in women on hormone replacement therapy.173,279 Obesity, smoking, and a sedentary lifestyle have also been incriminated in increasing neoplasia risk.189 In a Japanese study, cigarette smoking was found to be a risk factor for the development of colorectal adenoma.234 Naveau and colleagues reported that cirrhosis is an independent risk factor for colorectal adenomatous polyps and confirmed that alcoholism increases this risk.238 Immunodeficiency has also been suggested to play a possible role in the pathogenesis, but Parikshak and coworkers noted that transplant recipients are not more likely to develop metachronous polyps than the general population.253

include diet, lifestyle, and exposure to other carcinogens such as nicotine. Dietary factors associated with a predisposition to cancer include red meat, animal fats, and alcohol, whereas fresh fruit and fiber have a protective effect.4,186,269,295 Estrogen is a protective factor as shown by the reduced rate of polyps and cancer in women on hormone replacement therapy.173,279 Obesity, smoking, and a sedentary lifestyle have also been incriminated in increasing neoplasia risk.189 In a Japanese study, cigarette smoking was found to be a risk factor for the development of colorectal adenoma.234 Naveau and colleagues reported that cirrhosis is an independent risk factor for colorectal adenomatous polyps and confirmed that alcoholism increases this risk.238 Immunodeficiency has also been suggested to play a possible role in the pathogenesis, but Parikshak and coworkers noted that transplant recipients are not more likely to develop metachronous polyps than the general population.253

NEIL WILLIAMS SWINTON (1907-1980)

|

Swinton was born in Ontonagon, Michigan and spent his early years in Marquette. He attended Lehigh University and the University of Michigan, and he obtained his medical degree from the latter institution in 1929. Following postgraduate training in the department of surgery at the university, he became a fellow in surgery at the Lahey Clinic in Boston. He volunteered for duty at the start of World War II and served with distinction as commanding officer in a portable surgical hospital in the Southwest Pacific Theatre. Following the war, he returned to the Lahey Clinic as a staff surgeon and ultimately became one of the leaders in the field of proctology in the United States. Swinton wrote or coauthored 144 scientific papers, including the paper quoted that he wrote with his colleague, Shields Warren, chairman of the Department of Pathology at the New England Deaconess Hospital. Swinton was recognized by his colleagues through serving as president of the American Proctologic Society, now the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. He was an honorary fellow of the Section of Proctology of the Royal Society of Medicine. After 40 years as a surgeon at the clinic, he retired to Arizona, where he died.

SHIELDS WARREN (1898-1980)

|

Shields Warren was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts on February 26, 1898, the grandson of the first president of Boston University. He received a classical Greek and Latin education and entered Boston University, from which he graduated in 1918. Following a period of ill health and travel, he was admitted to Harvard Medical School, where he developed a lifelong interest in pathology. He received an appointment to the then world-renowned Pathology Department at Boston City Hospital. In 1927, he went to the New England Deaconess Hospital in Boston and established their Department of Pathology, remaining as chairman until 1963. Warren was recognized by his clinical peers as the “pathologist to the living” because of their reliance on his expertise in the decision-making process for the care of their patients. In 1948, he was appointed professor at Harvard Medical School. His interest in radiation and radiation injuries resulted in his involvement in the shipment of uranium ore during the Second World War. From 1947 until 1952, he assumed the post of head of the Division of Biology and Medicine at the Atomic Energy Commission. He died on July 1,1980 on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. (Abstracted from Corman ML. Landmark articles of the 20th century. Semin Colon Rectal Surg. 1999;10:209.)

Underlying these risk factors is the basic genotype that each individual inherits from his or her parents, and the occasional sporadic mutation or loss of heterozygosity that inevitably occurs in the course of life. Only 5% of colorectal neoplasia is associated with germ line mutations of a key gene that causes a syndrome of hereditary colorectal cancer (familial adenomatous polyposis, MYH-associated polyposis, Lynch syndrome). However, about 30% of colorectal cancers have less obvious forms of inheritance of colorectal cancer predisposition. These may include cancer-predisposing polymorphisms or poorly penetrant mutations that have not been characterized.

Geographic Distribution

Carcinoma of the colon and rectum is primarily a disease of Western civilization. The incidence of adenomatous polyps parallels the geographic distribution: high in Western societies (e.g., Europe, the United States, Australia, New Zealand), in other countries with high meat consumption, and in urban populations. The epidemiology of colorectal carcinoma is discussed in Chapter 23.

Anatomic Distribution

The distribution of colonic adenomas is similar to that of cancers: more frequent in the distal bowel, with a relatively high incidence in the cecum. In an autopsy study, Ekelund found that more than one-half of people had adenomas in the rectum and sigmoid colon, slightly fewer than those who were found to have a carcinoma.93 Nineteen percent of the benign lesions were in the right colon, virtually the same as the distribution for cancer. In Helwig’s series, the sigmoid colon was the most common site of adenomas, adenomas with malignant transformation, and carcinomas.137 Other studies have demonstrated a more uniform distribution for adenomas than for carcinomas, anticipating a future trend

to more proximal cancers. Greene noted that a left-to-right shift was apparent in the decade from 1971 to 1980 in comparison with the prior 10-year period.120 Thirty-two percent of adenomas were found in the rectum in the former decade and 13% in the latter.

to more proximal cancers. Greene noted that a left-to-right shift was apparent in the decade from 1971 to 1980 in comparison with the prior 10-year period.120 Thirty-two percent of adenomas were found in the rectum in the former decade and 13% in the latter.

Age

The National Polyp Study estimated that adenomatous polyps antedate cancer by an average of 10 years,350 a figure also suggested by Basil Morson.226 Corman reports the mean age of his patients who underwent colonoscopy-polypectomy was 55 years, compared with patients with colorectal cancer, whose mean age was 62 years. Adenomas occurring to those younger than the age of 40 are unusual and should raise a suspicion for an inherited syndrome. An adenoma in a patient younger than age 40 was one of the original Bethesda criteria, suggesting microsatellite instability (MSI) testing would be appropriate in this setting.32

Gender

Men and women have an approximately equal frequency of colorectal cancer; the same observation is true for adenomas. Women have a slightly greater number of right-sided lesions (both benign and malignant), and men have a tendency to rectal neoplasia.

Family History

Relatives of patients with adenomatous polyps have an increased risk of developing colorectal cancer, with an odds ratio that approaches 2.172 Winawer and colleagues interviewed a random sample of participants in the National Polyp Study who had newly diagnosed adenomatous polyps with respect to the history of colorectal cancer in parents and siblings.350 There were 1,031 patients with adenomas, 1,865 parents, and 2,381 siblings. The authors concluded that siblings and parents of patients with adenomatous polyps are at an increased risk for the development of colorectal cancer, particularly if the adenomas were diagnosed prior to the age of 60 years, or in the case of siblings, when a parent has had a colorectal cancer.350

TETSUICHIRO MUTO (1938-PRESENT)

|

Muto attended the University of Tokyo where he received his medical degree in 1963 and his PhD in 1968. He was an early user and advocate of the fiberoptic colonoscope. In a 1972 paper with Christopher Williams, he described the colonoscopy of the entire length of the colon in 50 patients. This paper showed the utility of colonoscopy to investigate cases of unexplained rectal bleeding, but the authors predicted that in the future, colonoscopy would likely be limited to specialized centers. They stated, “It seems likely that colonoscopy will be a specialist service provided in a few centres.” However, in the next year, 1973, he began to advocate for the spread of colonoscopic techniques to more hospitals. In that year, he published an early study on the safety of colonoscopic snare polypectomy with researchers at St. Mark’s Hospital in England. In that paper, the authors advocated the replacement of colotomy with colonoscopic polypectomy because of the lower risk of complications with the colonoscopic technique and recommended that hospitals “set up local facilities” for colonoscopy. In 1987, he published a retrospective study on 1,000 polyps removed colonoscopically. In the 1990s, screening colonoscopy for colorectal cancer became widespread. The flat adenoma of Muto was first characterized in his 1985 paper as an adenoma less than 1 cm in diameter, either flat or slightly raised, which often showed severe atypia. Since then, this entity has been the subject of many investigations. Tetsuichiro Muto also studied Crohn’s disease, diverticulosis, and cancer. He was the 10th director of the Cancer Institute Hospital of the Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research. He has been active in international conferences and societies and was the president of the International Society of University Colon and Rectal Surgeons in 2004. (Biography courtesy of Thomas Gregg, MD.)

Natural History of Adenomas

There are three situations in which the “natural” history of the adenoma-carcinoma sequence can be demonstrated: first, in the unusual circumstance where a patient with a benign polyp refuses removal of the lesion and subsequently develops a carcinoma at the same site; second, in familial polyposis, a condition that always results in a bowel cancer if the colon is not resected (see later); and third, in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (see Lynch Syndromes, Chapter 23). Because the histologic nature of the polyps in the familial polyposis condition is no different from that seen in the common solitary adenoma, one must infer that there is a cause and effect relationship. The huge number of polyps present in the bowel implies that the risk is multiplied many times.

Muto and coworkers reported four patients who had untreated adenomatous polyps.233 In one, cancer was diagnosed at the same site after 5 years; in the second, cancer was found after 6 years. The third patient had cancer of the rectum that developed 13 years after the original observation of a benign polyp. In the fourth case, after 11 years the tumor was still benign. The authors concluded that the life history of the adenoma-cancer sequence is probably at least 5 years and may in some cases be more than 10 years.

A retrospective review of Mayo Clinic records from a 6-year period prior to the development of colonoscopy revealed 226 patients with colonic polyps at least 1 cm in diameter for whom periodic radiographic examination was elected rather than colotomy and polypectomy.309 Actuarial analysis revealed that the cumulative risk of diagnosis of cancer at the polyp site at 5, 10, and 20 years was 2.5%, 8%, and 24%, respectively.

Patients with large, sessile, villous adenomas represent a special situation. Although rectal bleeding is the most frequent presenting complaint for both adenomatous conditions, change in bowel habits and mucous discharge are much more frequent concerns in a patient with a large villous adenoma. In fact, there is a unique symptom complex associated with villous adenoma that today has become quite rare: hypokalemia and dehydration. The syndrome was originally reported

by McKittrick and Wheelock in 1954 and is attributed to the loss of copious fluid and electrolytes from the mucussecreting tumor (Figure 22-16).220 Since this original article, many other reports have been published. Jeanneret-Grosjean and Thompson noted that sodium loss is as frequently seen and may actually be the dominant feature of this syndrome in some cases.168

by McKittrick and Wheelock in 1954 and is attributed to the loss of copious fluid and electrolytes from the mucussecreting tumor (Figure 22-16).220 Since this original article, many other reports have been published. Jeanneret-Grosjean and Thompson noted that sodium loss is as frequently seen and may actually be the dominant feature of this syndrome in some cases.168

LELAND STERLING MCKITTRICK (1893-1978)

|

Leland McKittrick was born in Thorp, Wisconsin, the son of a town physician. He attended the University of Wisconsin and graduated from Harvard Medical School in 1918. McKittrick began his surgical experience at the University of Minnesota but then transferred to the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. Following the completion of his training, he joined the surgical practice of a preeminent Boston surgeon, Daniel Fiske Jones. McKittrick was a thoughtful and innovative clinician. He introduced synchronous resection with ileostomy for ulcerative colitis, rather than employ the multistaged approach that had been in vogue, and he was also an advocate of side-to-end anastomoses in the bowel. In addition to his technical mastery, he was an authority on gastrointestinal pathophysiology. He was the first to recognize the electrolyte imbalance and fluid loss associated with villous adenomas of the large bowel. McKittrick took on a leadership role in surgery, not only in New England, but also nationally. He was elected president of the American Surgical Association in 1965. He retired from surgical practice at the age of 78 but pursued an active life until his death at age 85. (Reproduced in part from Drazan KE. Leland Sterling McKittrick. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:1494. Photograph courtesy of John McKittrick, MD.)

The lesions are frequently removed locally by a transanal approach and have a tendency to recur. Muto and associates observed the long-term follow-up in 10 such patients (5 to 30 years).233 All had periodic evaluation and further treatment as necessary for recurrence. Two patients subsequently developed cancers: one after 10 years and the other at 28 years.

Histology