Prognosis

Population-based studies

The importance of recognizing that the prognosis for referred patients differs from that of a regional population was recognized by Truelove and Pena over three decades ago [3]. They found that the survival of patients who were referred to Oxford (UK) from other regions was significantly reduced compared with that of patients who actually resided in the Oxford catchment area.

There are several population-based studies on the prognosis for patients with ulcerative colitis. Sinclair and associates described the prognosis of 537 patients with ulcerative colitis, seen between 1967 and 1976 in northeastern Scotland [4]. They found a high proportion of cases with distal disease (70%). The overall mortality and surgical resection rates in the first attack were both 3%. During this period of time, the mortality for severe, first-time attacks was 23%. However, there were only modest differences in the observed and expected mortality for the ulcerative colitis population. The colectomy rate after five years was 8%.

The prognosis and mortality associated with ulcerative colitis in Stockholm county were reported by Persson et al. [5]. In their review of 1547 patients followed from 1955 to 1984, they found that the mortality in the patient population was higher than that expected in the general population. After 15 years of follow-up, the survival rate was 94% of that expected based on the age and sex of the study population. The relative survival rates differed more for patients with pancolitis than for patients with proctitis, but the confidence intervals overlapped. While ulcerative colitis was the most important influence on the increased mortality, deaths from colorectal cancer, asthma and nonalcoholic liver disease were also increased.

Danish investigators have also reported the results of their population-based assessment of the prognosis of ulcerative colitis. Their population included 1161 patients with ulcerative colitis followed for up to 25 years (median 11 years) [6]. Of the 1161 patients, 235 underwent colectomy. Interestingly, 60 of these patients presented with proctosigmoiditis initially. The cumulative colectomy rate was 9%, 24%, 30% and 32% at 1,10,15 and 25 years respectively, after diagnosis. At any one time, nearly half of the clinic population was in remission. Prognostic factors associated with frequent relapses included: the number of relapses in the first three years after diagnosis and the year of diagnosis (1960s vs 1970s vs 1980s). Surprisingly, signs and symptoms of weight loss or fever were associated with fewer relapses on follow-up. A recent report on the same inception cohort of patients, published nearly ten years after these initial observations, has shown that overall life expectancy is normal for patients with ulcerative colitis, but patients over 50 years of age with extensive colitis at diagnosis have an increased mortality within the first two years, due to colitis-associated postoperative complications and co-morbidity [7].

Another report by the same investigators focused on the prognosis in children with ulcerative colitis [8]. Eighty of the 1161 patients in the cohort were children who presented with more extensive disease compared with adults. The cumulative colectomy rate did not differ from that of adults (29% at 20 years). At any interval from diagnosis, the majority of children were thought to be in remission.

Two prospective population studies are in progress in Europe (the European Collaborative Study on Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and the Inflammatory Bowel South Eastern Norway (IBSEN) cohort) but only one-year, follow-up data have so far been reported [9,10].

Extension of disease

Ayres and associates reported their experience with extension of disease in 145 patients presenting with proctitis or proctosigmoiditis, followed prospectively for a median of 11 years. By life-table analysis, extension occurred in 16% and 31% of patients at five and ten years’ follow-up respectively. Extension was associated with a clinical exacerbation of disease in most cases, but no specific clinical factors were associated with disease extension [11].

Much higher rates of progression have been reported, largely in retrospective non-population-based series. However, in the IBSEN cohort, 22% of 130 patients with a new diagnosis of ulcerative colitis had progressed to more extensive disease during the first year of follow-up [12]. The most recent study from Italy included 273 patients with proctitis [13]. It is retrospective and not population-based (patients were identified in 13 hospitals) but it is the largest cohort yet reported. Overall, proximal extension occurred in 27.1% during clinical and endoscopic follow-up: 20% at five years and 54% at ten years. However, the disease only extended into the sigmoid in the majority and into the splenic flexure in only 10% of the patients. An interesting observation was that smoking protected against disease progression on univariate analysis.

While research for the most part has focused on extension of disease, Langholz and colleagues report a much more dynamic pattern. After 25 years of follow-up, 53% of patients with limited disease had extension of disease, but in 75% of patients with extensive disease, the disease boundary had regressed [14]. This dynamic process, if confirmed by others, could have implications in terms of cancer surveillance programs. One potential explanation for these findings is that in the early years of the study, disease extent was assessed by radiological techniques.

Cancer surveillance (see also Chapter 17)

Although ulcerative colitis is a premalignant condition, the proportion of patients who develop cancer is small. In a population study using a retrospectively assembled cohort of patients the cumulative risk at 20 years of disease was about 7% and rose to 12% at 30 years [15]. This study is likely to have included all or nearly all patients with ulcerative colitis in two regions of England and one of Sweden and referral bias is probably minimal. Follow-up was both of long duration (17–38 years) and thorough (97%). On the other hand, in centers with an aggressive policy of colectomy, no increased cancer risk has been seen [16]. In all studies, length of history and extent of disease are important factors. Thus, left-sided colitis carries only a slightly increased risk while extensive colitis increases the risk about 20 times over that of an age and sex-matched population. Whether early age of onset of ulcerative colitis is an independent risk factor is controversial. Children tend to have extensive disease and have greater life expectancy than adults; they are, therefore, more likely to be at risk.

There is some controversy concerning the role of colonoscopic surveillance in detection of cancer. Most centers carry out colonoscopy in patients with extensive disease 8–10 years after diagnosis. Even at that stage, a few patients with dysplasia or a frank carcinoma will be identified. However, the subsequent pick-up rate during the surveillance program is small (about 11%) and in one center only two cancers were detected in 200 patients over a 20-year period [17]. Furthermore, cancers can develop outside the screening program. Thus, the need for colonoscopic surveillance has been questioned and no controlled study has shown that surveillance reduces mortality. However, in the published studies, the five-year survival rates for cancers detected in asymptomatic patients have been considerably higher than was observed in those presenting with symptoms. B4 C5

A second controversial area is the management of patients with endoscopically visible lesions. Where such lesions are associated with dysplasia in the adjacent mucosa (dysplasia-associated lesions or masses (DALMs)) the incidence of cancer appears to be very high and prophylactic colectomy is recommended [18, 19]. However, polyps for which there is no associated dysplasia in adjacent mucosa do not appear to carry this high risk of cancer, and in such cases conservative management rather than colectomy is recommended [20, 21]. B4 C5

Reviewing the evidence for dysplasia surveillance, Riddell recommended obtaining three to four biopsies every 10cm [22]. Annual colonoscopy is probably ideal, but two-yearly colonoscopy with intervening flexible sigmoidoscopy in alternate years is a compromise. Dysplasia detected at the initial screening colonoscopy should lead to colectomy, as there is a high chance of concomitant cancer. Indeed, most clinicians advocate colectomy whenever dysplasia is found, even when it is low grade. There is no doubt that such a policy abolishes the cancer risk but justification for it for patients with low grade dysplasia remains controversial [23,24]. The development of molecular markers may help to resolve the issue.

Treatment

The treatment of ulcerative colitis can be conveniently discussed for each category or class of medications, and in terms of either induction or maintenance of remission.

Aminosalicylates

With the discovery of sulfasalazine by Svartz [25], the first effective agent for the treatment of ulcerative colitis became available. The first trial that established the efficacy of sulfasalazine for the induction of remission was reported in 1962 [26]. Alc Misiewicz and colleagues were the first to study its efficacy as maintenance therapy [27]. An early randomized trial in the UK established the importance of continuous therapy [28]. Alc Azad Khan and the Oxford group established that 2g/day of sulfasalazine provided the optimal trade-off between efficacy and adverse effects [29].

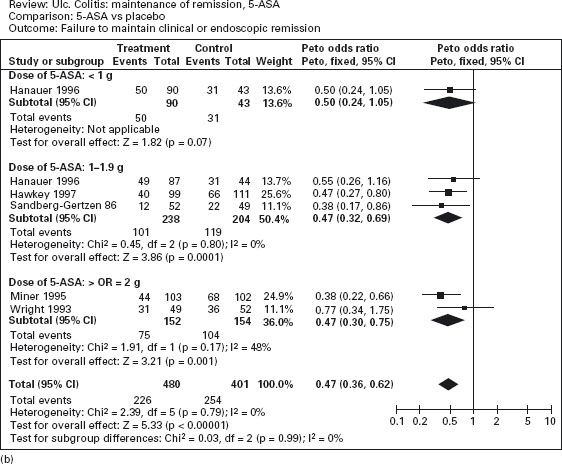

Figure 12.2 Failure to induce clinical or endoscopic remission in ulcerative colitis. Randomized controlled clinical trials of mesalamine (5-ASA) and sulfasalazine (SASP): (a) mesalamine (Expt) versus placebo (Ctrl), (b) mesalamine (Expt) versus sulfasalazine (Ctrl). (Source: Sutherland LR et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; 2: CD000543 [34]).

The finding that mesalamine (5-ASA) is the active moiety of sulfasalazine stimulated a decade of trials of induction and maintenance of remission [30, 31]. Numerous ami-nosalicylate delivery systems have been developed. These include drugs that release 5-ASA upon bacterial splitting of the azo bond (for example sulfasalazine, olsalazine and balsalazide), pH dependent release formulations (for example Asacol (pH 7) and Claversal/Mesasal/Salofalk (pH 6)), and a microsphere preparation (Pentasa) [32].

The efficacy of oral mesalamine has been evaluated by meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials [33–35]. As shown in Figure 12.2a, mesalamine is more effective than placebo for the induction of remission (pooled odds ratio 0.51; CI: 0.35–0.76) [34]. Ala The newer 5-ASA preparations were not significantly more effective than sulfasalazine, however, for active disease (pooled odds ratio 0.75; CI: 0.50–1.13) (see Figure 12.2b). On the other hand, adverse events were less frequently noted with mesalamine than with sulfasalazine: the number of patients needed to treat (NNT) with mesalamine rather than sulfasalazine to avoid an adverse event in one patient is approximately 7. Ala

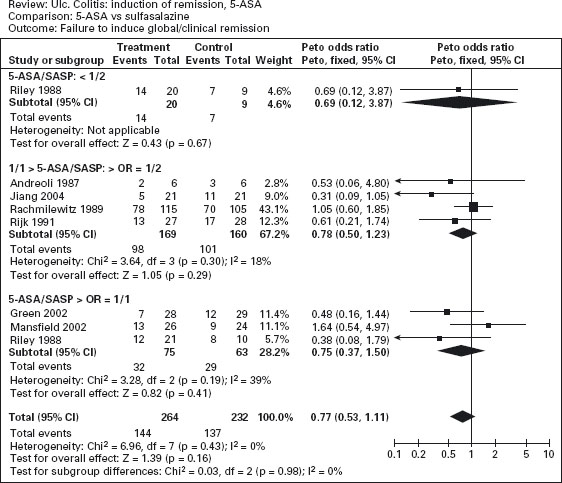

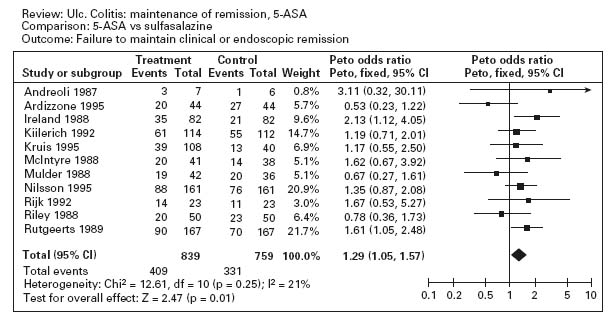

Figure 12.3a illustrates the results of a meta-analysis that demonstrates the superiority of aminosalicylates over placebo for maintenance of remission (pooled odds ratio 0.47; CI: 0.36–0.62) [35]. Ala Conflicting results were obtained in studies comparing sulfasalazine with mesalamine for maintenance therapy. The overall results are shown in Figure 12.3b; sulfasalazine appeared to be more effective than mesalamine (pooled odds ratio 1.29; CI: 1.05–1.57). Ala When only studies with a minimum of 12 months’ follow-up were included in the analysis, however, there was no statistically significant advantage for sulfasalazine (pooled odds ratio 1.15; CI: 0.89–1.50). There are a number of possible explanations for this discrepancy. First, the observation in the overall analysis may be correct: sulfasalazine may be a more effective delivery system than mesalamine. Second, the analysis that was restricted to studies with 12 months’ follow-up might have lacked sufficient statistical power to detect a small difference in efficacy. Third, the high drop-out rate with olsalazine therapy might have biased the overall results against mesalamine. Finally, it is possible that the comparison studies suffered from selection bias. With the exception of one trial, the inclusion criteria included tolerance to sulfasalazine [36]. This factor would tend to minimize the occurrence of adverse events with sulfasalazine therapy.

Figure 12.3 Failure to maintain clinical or endoscopic remission in ulcerative colitis. Randomized controlled clinical trials of mesalamine (5-ASA) and sulfasalazine (SASP): (a) mesalamine (Expt) versus placebo (Ctrl), (b) mesalamine (Expt) versus sulfasalazine (Ctrl). (Source: Sutherland LR et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; 4: CD000544 [35]).

Several oral 5-ASA preparations are available, but two warrant special mention. Olsalazine and balsalazide appear to be approximately as effective as sulfasalazine and mesalamine in the treatment of active ulcerative colitis and in the maintenance of remission. There have been concerns about the development of secretory diarrhea with olsalazine [37, 38], due to interference with Na+/K+-ATPase, but the frequency of this adverse effect can be minimized by taking the medication in divided doses with meals [39,40]. Moreover, systemic absorption of 5-ASA and its metabolites is less with olsalazine than with mesalamine, which might translate into a smaller risk of nephropathy [41, 42]. Several randomized controlled trials have demonstrated a slight (and statistically insignificant) advantage of balsalazide (in a dosage of 6.75g/day) to sulfasalazine 3g/ day or mesalamine 2.4g/day in the treatment of active ulcerative colitis. Ald The newer agent may provide relief of symptoms and sigmoidoscopic healing more quickly than mesalamine [43–45], and may be better tolerated [46]. Balsalazide 3g/day appears to be as effective as mesalamine 1.2g/day at maintaining remission, and may provide better relief of nocturnal symptoms in the first three months of maintenance therapy [47]. It should be noted that these observations suggesting small advantages of balsalazide over mesalamine depend on post hoc subgroup analyses of relatively small groups of patients and should be interpreted with some caution.

Topical therapy is a logical option for patients with disease limited to the distal colon. In theory, it presents a high concentration of mesalamine to the affected area, while minimizing systemic absorption. Marshall and Irvine have published two meta-analyses of topical therapy [48, 49]. The first analysis established that topical mesalamine was effective for both induction and maintenance therapy in patients with distal disease [48]. Alc The second analysis found that mesalamine was more effective than topical corticosteroids for the induction of remission [49]. Alc Foam enemas can reliably deliver mesalamine to the rectum and sigmoid colon, and sometimes even to the descending colon, in healthy individuals and patients with ulcerative colitis [50–53]. Foam enemas are superior to placebo, and are at least as easily tolerated and effective as liquid enemas [54–56]. Gel enemas may be better tolerated than foam preparations [57]. Mesalamine suppositories have been shown to be effective for the maintenance of remission of ulcerative proctitis [58]. Ald

Some patients may benefit from a combination of oral and topical 5-ASA preparations. A small randomized trial performed by Safdi et al. suggested that combined topical and oral 5-aminosalicylate therapy may be more effective than oral therapy alone [59]. This result was confirmed by Marteau et al. in a large randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in which 127 patients with mild to moderately active colitis were randomized to receive either a 5-aminosalicylate enema or a placebo enema for the first four weeks of treatment with oral 5-ASA 4g/day [60]. At eight weeks the observed remission rates were: 5-ASA enema 64%, placebo enema 43%, p = 0.03.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids remain the standard therapy for moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Truelove and Witts were the first to undertake a randomized, controlled trial of cortisone in patients with active colitis, and showed that 100mg/day, followed by tapering over six weeks, was an effective treatment [61]. Alc Lennard-Jones and associates reported similar efficacy for prednisone [62]. It appears that once daily dosage yields similar effectiveness as divided doses of the medication [63].

The assumption that there is no additional benefit from the use of more than 40mg/day of prednisone is based on a small randomized trial conducted by Baron and colleagues [64]. This trial compared the outcomes of 58 outpatients who were randomized to 20, 40, or 60 mg of prednisone per day. Although either 40 or 60mg/day yielded better results than 20mg/day, no difference in results was observed in patients given 40 versus 60 mg/ day. The study included too few patients, however, to have sufficient statistical power to rule out a relative benefit from the 60 mg dose. Ald

Budesonide is a potent second-generation corticosteroid with 90% first pass metabolism, resulting in decreased systemic toxicity [65]. A randomized, controlled trial demonstrated that a targeted colonic release formulation of budesonide appeared to be as effective as prednisolone and exhibited a more favorable adverse event profile [66]. Ald

Budesonide enemas have also been used for active distal disease. A meta-analysis published by Marshall and Irvine documented that they are as effective as conventional steroid enemas [67]. Alc The only published trial comparing budesonide enemas with 5-ASA enemas revealed no differences in endoscopic or histopathologic scores between the treatment groups, but the clinical remission rate was greater with 5-ASA (60% vs 38%, p = 0.03) [67].

Most reported trials have demonstrated no benefit for corticosteroids in the maintenance of remission of ulcerative colitis [68–70].

Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine

Most trials of anti-metabolite drugs in ulcerative colitis have been small. There is no evidence that azathioprine (2–5mg/kg/day) combined with prednisolone induces remission more effectively than steroids alone [71]. Alc

Nevertheless, azathioprine has been shown to have a steroid-sparing effect at doses between 1.5 and 2.5mg/kg/ day, and the major indication for this drug in ulcerative colitis is for patients who require continuing steroid therapy [72, 73].

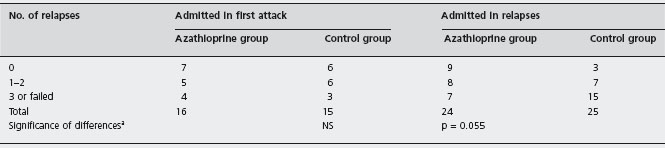

In the double-blind, randomized, controlled trial conducted by Jewell and Truelove, patients who had gone into remission during the acute stage were weaned off steroids and given either placebo or maintenance therapy with azathioprine for one year [71]. Overall, azathioprine offered no statistically significant advantage over placebo for reducing the relapse rate. There may have been some benefit to azathioprine, however, in the subgroup of patients who were treated for relapsing disease, as opposed to those who presented with their first episode of colitis, as illustrated in Table 12.1. Specifically, 9 of 24 azathioprine-treated patients in the former group had no relapse during follow-up, compared with 3 of 25 patients given placebo. More detailed post hoc analysis revealed that only seven patients in the azathioprine group experienced at least three relapses or failed therapy, compared with 15 patients in the placebo group (p = 0.055). These analyses should be interpreted with caution because they represent post hoc subgroup analyses of small numbers of patients.

Table 12.1 Clinical course during trial in two treatment groups of patients according to whether patients entered trial in first attack of ulcerative colitis or in relapse.

a Fisher’s exact test.

Reproduced from Jewell DP et al. BMJ 1974; iv: 627–630 [71].

Hawthorne and colleagues conducted an azathioprine withdrawal trial that suggested a benefit for this drug in the maintenance of remission [74]. In this study, patients who were in long-term remission while taking azathioprine were randomized to continue with the medication or take placebo. During the subsequent year of follow-up, patients receiving placebo relapsed significantly more often than did those who remained on azathioprine. Ald It should be pointed out, however, that this type of trial design cannot be used to estimate the size of the treatment effect from an intervention. It is possible that only a small proportion of patients can be maintained in remission with azathioprine, and that most of these patients would relapse if the drug were withdrawn. More recently, Sood et al. randomized 35 patients with newly diagnosed ulcerative colitis, all of whom received corticosteroids to induce remission, to receive either sulfasalazine and azathioprine, or sulfasalazine and a placebo for one year [75]. Four patients (23.5%) who received azathioprine suffered relapse of disease, compared to 10 (55.6%) who received sulfasalazine alone (p < 0.05). Ald This is somewhat stronger evidence that azathioprine is beneficial for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis, but the results should be confirmed with a larger study.

A single small randomized trial reported by Maté-Jimenez et al. using 6-mercaptopurine rather than azathioprine showed 6-mercaptopurine to be more effective than methotrexate or 5-ASA for induction and maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis (see below) [76]. Ald

Methotrexate

There have been anecdotal reports of the steroid-sparing effects of methotrexate in patients with chronic active ulcerative colitis. In a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial 67 patients with steroid-dependent disease were randomized to either oral methotrexate 12.5mg per week (30 patients) or placebo (37 patients) for nine months [77]. No benefit was demonstrated for methotrexate in terms of disease activity, remission rate or steroid dosage. Alc

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree