Management of complications specific to primary sclerosing cholangitis

Dominant biliary strictures may be treated endoscopically, either via balloon dilatation or the placement of a biliary stent. No randomized trials have compared the different endoscopic treatment options. However, balloon dilatation has become the preferred option as biliary stents are prone to occlusion and therefore predispose to infection [97]. Stenting after dilatation provides no added value. Gluck et al. evaluated the survival of 106 PSC patients who under went endoscopic therapy over a 20-year period and observed that patient survival at years three and four was significantly higher than that predicted by the Mayo Clinic natural history model for PSC [98]. In a 13-year prospective study Stiehl et al. studied the survival of 106 patients with PSC treated with 750 mg UDCA daily and by endoscopic balloon dilatation of major dominant stenoses whenever necessary [99, 100]. Ten patients had a dominant stricture at entry and over a median follow-up of five years another 43 developed a dominant stenosis. This was not prevented by low dose UDCA treatment, but successfully treated by balloon dilatation in the majority, only five requiring tem porary stenting. This combined approach of UDCA and endoscopic intervention significantly improved the sur vival compared with predicted survival rates. This was an uncontrolled study and provides only relatively weak evi dence that UDCA and/or endoscopic therapy prolonged survival, although the results are promising. Where LT is precluded, as in biliary obstruction due to cholangiocarci noma, endoscopic stenting is undoubtedly the best option for more distal lesions.

Selected non-cirrhotic PSC patients with dominant ext-rahepatic strictures may benefit from a bilioenteric bypass [101]. Extrahepatic biliary resection (EHBR) is also poten tially effective in carefully selected non-cirrhotic patients. In 2008, Pawlik and colleagues published data on the peri-operative morbidity and long-term survival of the largest cohort of patients (n = 77) who had undergone EHBR over the longest follow-up period ever reported (median 10.2 years) [102]. Results were promising, with non-cirrhotic patients demonstrating three, five and ten-year survival rates of 89.6%, 83.3% and 60.2% respectively. This com pared favorably with PSC patients who had undergone liver transplantation whose corresponding survival rates were 87.4%, 67.3% and 57% respectively. Furthermore, none of the patients treated with EHBR developed cholan-giocarcinoma during the follow-up period. There was a striking contrast in short and long-term survival, with approximately 40% of cirrhotic patients dying within one year of surgery, compared to 5% in the non-cirrhotic cohort. A ten-year survival rate of only 12% was observed in cir-rhotics. In addition, EHBR was also associated with low perioperative morbidity and mortality, and also a low rate of PSC-related hospital readmissions.

PSC patients with dominant biliary duct strictures are at increased risk of developing secondary bacterial infections necessitating the need for antibiotic therapy. Kulaksiz and colleagues conducted the first study to evaluate the role of fungal infections in patients with PSC [103]. In a prospec tive, non-randomized trial, 148 bile samples were obtained endoscopically from 67 consecutive patients. Candida species were isolated from eight (11.9%) patients and of these, seven had dominant strictures requiring multiple endoscopic dilatations and courses of antibiotics, suggest ing these treatment modalities may have predisposed to colonization with the fungus. The efficacy of antifungal agents and the effect of Candida infections on the outcome of PSC patients after liver transplantation will need to be evaluated in future trials.

Medical therapy – the prevention of disease progression

In both PBC and PSC the primary site of inflammation and damage is the biliary epithelium. When severely damaged or destroyed the bile ducts do not have the capac ity to regenerate like hepatocytes, which are the primary target for injury in various parenchymal liver diseases. Given the finite number of bile ducts in the liver the natural history of PSC, like PBC, is that of progressive loss of functioning intrahepatic bile ducts (ductopenia). This duc-topenia leads to a progressive and irreversible failure of hepatic biliary excretion. To delay and reverse this process physicians have tried a variety of agents, but in PSC, in contrast to PBC, few randomized controlled trials have been done.

Ursodeoxycholic acid

This hydrophilic bile acid has become widely used in the treatment of cholestatic liver of all causes. UDCA appears to exert a number of effects, all of which may be beneficial in chronic cholestasis: a choleretic effect by increasing bile flow; a direct cytoprotective effect; an indirect cytoprotec-tive effect by displacement of the more hepatotoxic endog enous hydrophobic bile acids from the bile acid pool; an immunomodulatory effect; and finally an inhibitory effect on apoptosis.

Using a labeled bile acid analog Jazrawi et al. demon strated a defect in hepatic bile acid excretion, but not in uptake in patients with PBC and PSC, resulting in bile acid retention [104]. They observed an improvement of hepatic excretory function with UDCA in patients with PBC but only a trend towards improvement in the small number of patients with PSC. Not only is hepatic bile acid excretion affected by UDCA but so is ileal reabsorption of endog enous bile acids. The net result is enrichment of the bile acid pool with UDCA. Hydrophobic bile acids are more toxic than UDCA, which can protect and stabilize membranes.

Studies have demonstrated that long-term treatment with UDCA decreases aberrant expression of HLA class I on hepatocytes and reduces levels of soluble cell adhesion molecules (sICAM) in PBC patients. In vitro studies have shown that UDCA may alter cytokine production by human peripheral mononuclear cells. In PSC one study has shown that UDCA has been shown to decrease aberrant HLA DR expression on bile ducts [105]. However, a more recent study could not demonstrate any alteration in expression of either HLA class I and II or ICAM-1 on either biliary epithelial cells or hepatocytes [106]. The body of evidence suggests that UDCA does have some modulatory effects on immune function, but how important these are remains unclear.

Numerous studies have attempted to address the clinical efficacy of UDCA treatment in PSC. The majority have been uncontrolled studies in small numbers of patients. In a pilot study O’Brien et al. treated 12 patients with UDCA on an open basis over 30 months [107]. They documented improvement in fatigue, pruritus and diarrhea and signifi cant improvement of all liver biochemical tests, particu larly alkaline phosphatise, during the two UDCA treatment periods. Symptoms and liver biochemistry relapsed during a six-month withdrawal period between treatment phases. During UDCA treatment the amount of cholic acid declined slightly but the levels of other relatively hydrophobic bile acids did not change significantly.

In the first randomized double-blind controlled trial of UDCA in PSC Beuers et al. compared over a 12-month period six patients who received UDCA 13–15mg/kg bod-yweight with eight patients who received placebo [108]. The majority of patients had early disease (Ludwig classi fication stages I and II). After six months a significant reduction in alkaline phosphatase and aminotransferases was achieved in the treatment group. A significant fall in bilirubin was only noted after 12 months. Using a multi-parametric score the UDCA-treated group showed signifi cant improvement in their liver histology, mainly attributed to decreased portal and parenchymal inflammation. Unfortunately treatment did not ameliorate their symptoms.

Similar results were obtained by Stiehl et al. who rand omized 20 patients to either 750 mg daily of UDCA or placebo [109]. However, in a larger randomized placebo-controlled trial of UDCA in PSC by Lindor et al. no benefit was demonstrated [110]. In this trial 105 patients were ran domized to treatment with UDCA in conventional doses (13–15mg/kg bodyweight daily) or placebo and followed up for up to six years (mean 2.9 years). Treatment with UDCA had no effect upon the time until treatment failure, defined as death, liver transplantation, the development of cirrhosis, quadrupling of bilirubin, marked relapse of symptoms or the development of signs of chronic liver disease. Furthermore, the significant improvement in liver biochemical tests seen in the treated group was not reflected by any beneficial changes in liver histology. A1d

In the early 2000s, two pilot studies were performed in order to investigate the efficacy of higher than conven tional doses of UDCA in the management of patients with PSC. On the basis that the higher dose would provide adequate enrichment of the bile acid pool and enhance immunomodulatory effects, the Oxford group studied the efficacy of UDCA at a daily dose of 20mg/kg in a double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial involving 26 patients over a two-year period [111]. The investigators reported signifi cant improvements in most outcomes measured, including liver biochemistry, cholangiographic appearances and his-tological grade of liver fibrosis, in those randomized to the high dose UDCA. Symptomatic improvement was not evident. An open-label study from the Mayo Clinic reported a significant reduction in expected mortality at four years using the Mayo risk score in patients using UDCA at a dose of 25–30mg/kg/day in comparison to those taking lower doses (13–15mg/kg/day) or placebo [112]. A significant improvement of liver biochemistry was also noted. However, radiological and histological outcomes were not measured. In 2005, Olsson et al. published the findings of the largest placebo-controlled, prospective trial of high-dose UDCA to date [113]. During the five-year study period, 110 PSC patients received UDCA (17–23mg/kg/ day) and their results were compared with 109 patients in the placebo group. Although there was a trend towards increased survival in the UDCA-treated group, this was statistically insignificant as the study was underpowered. There was no statistical difference between the two groups in symptom profile, quality of life or in the number of patients diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma. The primary endpoint of the study was liver transplantation or death, and whilst the incidence of this was lower in the UDCA-treated group, it did not reach statistical significance (7.2% vs 10.9%, 95% CI: 12.2– 4.7%, p = 0.368). In all three studies, the higher doses were well tolerated. A1c

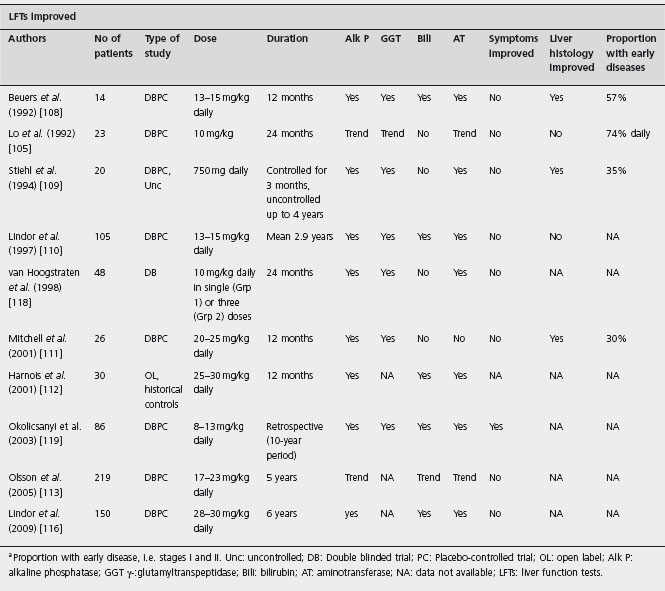

Cullen and colleagues conducted a double-blinded, ran domized dose-ranging trial to determine whether further enrichment of the bile acid pool with UDCA would lead to additional benefits in outcome for PSC patients [114]. Thirty-one patients were randomized to treatment with 10 mg/kg, 20 mg/kg or 30 mg/kg daily of UDCA for two years. A1d As expected, higher doses of UDCA led to further improvements in liver biochemistry compared to more conventional lower doses. Greater reductions in the Mayo risk score were noted in patients who had received the higher doses of UDCA. No significant changes in liver histology among the three groups were observed, which was not surprising given the short follow-up period. Biliary enrichment of UDCA increased with increasing dose, and after two years of treatment biliary UDCA represented 65.6% of total bile acids in the 10mg/kg group, 79.3% in the 20mg/kg group, and 92.6% in the 30mg/kg group. This is in contrast to the findings reported by Rost et al. who observed a plateau in bile enrichment after daily doses beyond 22–25mg/kg. High-doses of UDCA were well tol erated, and in particular, exacerbations of diarrhea in those with underlying colitis were not reported [115]. However, a multicenter randomized trial from the USA comparing high dose UDCA (28–30mg/kg) with placebo in PSC patients has been halted prematurely because of a higher incidence of adverse outcomes in the UDCA group [116] (see Table 34.4). Thus, at present, high dose UCDA cannot be recommended.

By virtue of its different physiological properties to standard UDCA, Fickert et al. investigated the therapeutic effects of 24-norursodeoxycholic acid (norUDCA), a C23 homologue of UDCA with one fewer methylene group in its side chain, using mutidrug resistant gene 2 knockout mice (Mdr2-/-) as an animal model for PSC [117]. Mdr2-/-mice that received a diet containing norUDCA demon strated a significant improvement in their liver biochemistry and histology, in comparison to mice that were fed UDCA. In addition, a marked reduction in hydroxyproline content and the number of infiltrating neutrophils and proliferat ing hepatocytes and cholangiocytes was observed in the norUDCA group. Proposed mechanisms of action of norUDCA include increased hydrophilicity of biliary bile acids, stimulation of bile flow with flushing of injured bile ducts, and induction of detoxification and elimination routes for bile acids.

aProportion with early disease, i.e. stages I and II. Unc: uncontrolled; DB: Double blinded trial; PC: Placebo-controlled trial; OL: open label; Alk P: alkaline phosphatase; GGT γ-:glutamyltranspeptidase; Bili: bilirubin; AT: aminotransferase; NA: data not available; LFTs: liver function tests.

Corticosteroids

Systemic and topical corticosteroid therapy has been evalu ated in a number of small, often uncontrolled, trials, but there is no direct evidence to suggest that they are benefi cial in PSC. Indeed, when PSC patients with coexistent UC are given corticosteroids for treatment of their colitis, this treatment appears to have little influence on the behavior of their liver disease. B4 A recent finding that a rat model of cholangitis possesses fewer glucocorticoid receptors on hepatic T lymphocytes may explain the ineffectiveness of steroids in human PSC [120].

In one study, ten patients diagnosed by ERCP and liver biopsy with early PSC (elevated serum alkaline phos phatase, but none with biliary cirrhosis) were treated with prednisone without a significant response [121]. In another uncontrolled pilot study ten patients with PSC, selected because they had elevated aminotransferases, were given prednisolone, and the majority responded with improve ment in their biochemistry [122]. In a subsequent study Lindor et al. were unable to confirm these optimistic results [123]. They treated 12 patients with a combination of low dose prednisone (10 mg daily) and colchicine (0.6 mg twice daily). The clinical course of the treated patients was com pared with a control group, but the study was not rand omized. After two years no significant differences in the biochemistry and liver histology were detected between the two groups. In this study treatment did not alter the rate of disease progression or improve survival. The absence of a beneficial response, and the suspicion that corticosteroid therapy enhanced cortical bone loss and hence the risk of developing compression fractures of the spine even in young male patients, led the authors to advise against empirical corticosteroid therapy in these patients. This conclusion was strengthened by the observa tion that spontaneous fractures in patients who have undergone liver transplantation occur almost exclusively in PSC patients who are already osteopenic at the time of transplantation [124].

Topical corticosteroids are usually administered through a nasobiliary drain left in situ following ERCP. The only controlled trial of nasobiliary lavage with corticosteroids from the Royal Free Hospital showed no benefit when com pared with a placebo group [125]. Although the numbers were small, the bile of all the treated patients became rapidly colonized with enteric bacteria and a higher incidence of bacterial cholangitis was recorded in the treatment group.

More recent clinical trials have studied the possible benefit of budesonide, a second-generation corticosteroid with a high first-pass metabolism and minimal systemic availability. Unfortunately preliminary results both alone and in combination with UDCA have been disappointing [126,127]. A1d

There is emerging evidence that corticosteroids may be of value in patients who have overlap syndromes between PSC and autoimmune hepatitis, and in the subgroup of PSC patients who have elevated immunoglobulin G4 levels [128].

Other immunosuppressants

Despite the evidence that PSC may be an immune-medi ated disease, there have been few randomized controlled trials of immunosuppressive agents containing sufficient numbers of patients with early disease. Immunosuppressi on is unlikely to be effective in patients with advanced liver disease and irreversible bile duct loss, and this may account for the disappointing results so far seen in PSC with these agents.

No controlled trials of azathioprine in PSC have been reported. In one case report two patients improved clini cally on azathioprine but in another the patient deterio rated [129, 130]. The use of cyclosporine in PSC has been evaluated in a randomized controlled trial from the Mayo Clinic involving 34 patients with PSC and, in the majority, coexistent ulcerative colitis [131]. Treatment with cyclosporine reduced the symptoms of ulcerative colitis but had no effect on the course or prognosis of PSC [132]. A1d Follow-up liver histology after two years of treatment revealed progression in 9/10 of the placebo group but only 11/20 of the cyclosporine-treated group. This was not reflected by any beneficial effect on the biochemical tests. The prevalence of adverse effects was low; serious renal complications were not reported. A combination of cyclosporine and prednisolone elicited a beneficial response in a 65-year-old man with PSC accompanied by pancreatic duct abnormalities [133].

Methotrexate

After demonstrating a promising response to low dose oral pulse methotrexate in an open study involving ten PSC patients without evidence of portal hypertension [134], Knox and Kaplan carried out a double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial of oral pulse methotrexate at a dose of 15mg per week [135]. Twelve patients with PSC were entered into each group and followed up for two years. Although, a significant fall in the serum alkaline phos-phatase by 31% was observed in those receiving meth otrexate, there were no significant improvements in liver histology, treatment failure or mortality rates. A1d In a pilot study Lindor et al. found that methotrexate given in combination with UDCA to 19 PSC patients was associated with toxicity (alopecia, pulmonary complications), but showed no additional improvement in liver biochemistry compared with a control group of nine patients treated with UDCA alone [136].

Tacrolimus

Preliminary results from a small pilot study evaluating the benefit of tacrolimus were encouraging, with all ten PSC patients displaying a marked improvement in their liver biochemistry, without the development of significant side effects [137]. Talwalker et al. conducted an open-label, phase 2 study, during which, 16 patients received tac rolimus at a dose of 0.05mg/kg twice daily for one year [138]. A considerable proportion (81%) of patients experi enced drug-related adverse effects, with 31% developing toxicities necessitating withdrawal from the study. Of the eight patients who completed the year of treatment, signifi cant improvements in median serum ALP and AST levels were observed. It has been suggested that the poor toler-ability of the drug may limit its use in the future.

Mycophenolate motefil

Two studies failed to demonstrate a significant benefit of mycophenolate motefil (MMF) in the treatment of patients with PSC. Sterling and colleagues reported results from a randomized-controlled study in which 25 patients received either UDCA (13–15 mg/kg) alone or in combination with MMF at a dose of 1 g twice a day [139]. After two years, no significant differences were demonstrated with respect to liver biochemistry levels, histological and cholangiographic appearances between the two groups. A1d An open-label study performed at the Mayo Clinic evaluated the efficacy and safety of MMF as a single agent in 30 patients with established PSC over a one-year period [140]. Although a statistically significant reduction in ALP levels was observed, there was no such improvement in the other liver function tests or Mayo risk score. Furthermore, the drug was not well tolerated, with seven patients withdrawing from the study due to drug-related adverse effects. Both studies included a substantial proportion of patients with advanced fibrosis and therefore immune-mediated inflam mation would be minimal, which may account for the lack of efficacy of MMF.

Cladribine, a nucleoside analog with specific antilymphocyte properties, has been used to treat a variety of autoimmune disorders. In a recent pilot study in PSC six patients with early disease were treated for six months and followed for two years. Whilst significant decreases were seen in peripheral and hepatic lymphocyte counts no sig nificant changes were observed in symptom scores, liver function tests or cholangiograms [141].

Anti TNF-α agents

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) has been suggested to drive local inflammatory responses in PSC, and on this basis infliximab has been evaluated as a potential therapeu tic agent. Hommes et al.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree