Table 14.1 Annual incidence per 100,000 inhabitants of collagenous and lymphocytic colitis in population based epidemiological studies.

| Region and study period | Collagenous colitis | Lymphocytic colitis |

| Örebro, Sweden, 1984–88 [3] | 0.8 | |

| Örebro, Sweden, 1989–93 [3] | 2.7 | |

| Örebro, Sweden, 1993–95 [6] | 3.7 | 3.1 |

| Örebro, Sweden, 1996–98 [6] | 6.1 | 5.7 |

| Örebro, Sweden 1999–2004 [8] | 5.2 | 5.5 |

| Terrassa, Spain, 1993–97 [4] | 2.3 | 3.7 |

| Iceland, 1995–99 [5] | 5.2 | 4.0 |

| Olmsted, USA 1985–89 [7] | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Olmsted, USA 1990–93 [7] | 1.6 | 1.0 |

| Olmsted, USA 1994–97 [7] | 3.9 | 6.4 |

| Olmsted, USA 1997–2001 [7] | 6.2 | 12.9 |

| Calgary, Canada 2002–2004 [9] | 4.6 | 5.4 |

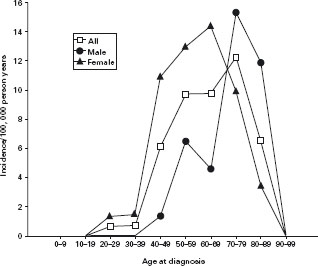

Figure 14.2 Age and sex-specific incidence of lymphocytic colitis. Reprinted with permission from Olesen et al. Gut 2004; 53: 346–350 [6].

Lymphocytic colitis

The histopathologic diagnostic criteria of lymphocytic colitis are:

- Epithelial lesions

- An increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes (>20 lym phocytes per 100 epithelial cells)

- Infiltration of the lamina propria with lymphocytes and plasma cells, in the absence of an increase of the collagen layer (See colour plate 14.2) [2, 29]

An increased number of intraepithelial T-lymphocytes may also be seen in the terminal ileum [28].

A recent blinded and independent study of the observer variability in diagnosing microscopic colitis histopatho-logically, showed that the interobserver agreement with final diagnostic categories was 91% [30], indicating that the histopathologic criteria are consistent and reproducible.

Etiology and pathophysiology

The etiology of microscopic colitis is largely unknown. At present, both collagenous and lymphocytic colitis are considered to be caused by an abnormal immunologic reaction to various mucosal insults in predisposed individuals.

Genetics

Data on genetics are sparse. A small number of familial cases with collagenous and lymphocytic colitis, and with mixed collagenous and lymphocytic colitis has been reported [31–35]. Twelve percent of patients with lym-phocytic colitis reported a family history of other bowel disorders such us inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease or collagenous colitis [12]. A recent study showed a significant association between both collagenous colitis and lymphocytic colitis and HLA-DR3-DQ2 [36]. Another study showed that HLA-DQ2 or DQ1,3 were seen more frequently in microscopic colitis than in controls, which indicate that there may be a partly genetic background for the diseases [37]. However, other studies have shown less strong associations [38], and there is no association found between NOD2/CARD15 gene polymorphisms and collagenous colitis [39].

Reaction to a luminal agent

The increased number of T-lymphocytes in the epithelium has supported the theory that collagenous colitis may be caused by an abnormal immunologic reaction to a luminal agent [40–42]. The observation, that diversion of the fecal stream by an ileostomy normalises or reduces the characteristic histopathologic changes in collagenous colitis, further supports this theory [43]. Recurrence of symptoms and histopathologic changes were seen after closure of ileostomy. Furthermore, abnormalities of colonic histology resembling lymphocytic colitis have been reported in untreated celiac disease [44].

A recent cytokine study in both collagenous and lymphocytic colitis demonstrated a TH1-cytokine profile, with increased IFN-γ and TNFα, and normal levels of IL-2, IL-4 and IL-10 [45]. A down-regulation of E-cadherin and ZO-1 was observed, and another study demonstrated a decrease in occludin and claudin-4 expression [46]; both events might result in an impaired function of tight junctions. Taha et al. found a significant correlation between the increased concentrations of eosinophil cationic protein and albumin in rectal perfusate, indicating a disturbed mucosal permeability [47].

Infectious agent

The sudden onset of the disease in some patients, and the effects of various antibiotics support a possible infectious cause [10]. An association with microscopic colitis and infections with Campylobacter jejuni [48] and Clostridium difficile [49–51] has been reported. In another study, Yersinia enterocolitica was detected in three of six patients prior to the collagenous colitis diagnosis, and a serologic study showed that antibodies to Yersinia species were more common in collagenous colitis patients than in healthy controls [52, 53]. “Brainerd diarrhea” is the term applied to an outbreak of chronic watery diarrhea characterised by acute onset and prolonged duration [54]. An infectious cause has been suspected but the responsible agent has not been identified. Colonic biopsies in these patients show epithe-lial lymphocytosis similar to lymphocytic colitis but the surface epithelial lesions are absent.

Table 14.2 Drugs reported in association with microscopic colitis.

| Lymphocytic colitis | Collagenous colitis |

| Ticlopidine [57-59] | Lanzoprazole [60, 61] |

| Cyclo 3 Fort [62 – 64] | NSAID [55] |

| Ranitidine [65] | Cimetidine [66] |

| Vinburnine [67] | |

| Tardyferon [68] | |

| Flutamide [59] | |

| Acarbose [69] | |

| Piroxicam [70] | |

| Levodopa-benserazide [71] | |

| Carbamazepine [12, 72, 73] | |

| Sertraline [12] | |

| Paroxetine [12] | |

| Oxetorone [74] | |

| Lanzoprazole [61, 75] |

Drugs

There are several reports of drug-induced microscopic colitis, especially lymphocytic colitis (Table 14.2). Most reports concern ticlopidine and Cyclo 3 Fort. In a case-control study the use of NSAIDs was significantly more common in collagenous colitis patients than in controls, and discontinuation of NSAIDs was followed by improvement of the diarrhea in some patients [55]. Others found that use of NSAIDs at presentation was associated with a greater need for 5-ASA and steroid therapy, possibly reflecting a more resistant form of disease, but withdrawal of NSAIDs did not improve clinical symptoms in that study [56]. The increased use of NSAIDs in collagenous colitis observed in collagenous colitis patients compared to controls is possibly due to the occurrence of concomitant arthritis. The number of reported cases of drug-induced microscopic colitis is small and chance associations are possible. It is, however, important to assess concomitant drug use in patients and consider withdrawal of drugs that may worsen the condition.

Autoimmunity

Both collagenous and lymphocytic colitis are associated with autoimmune diseases. An autoimmune pathogenesis has therefore been proposed, possibly initiated by a foreign luminal agent that causes an immunologic cross-reaction with an endogenous antigen. A study of autoantibodies and immunoglobulins in collagenous colitis showed that the mean level of IgM in collagenous colitis patients was significantly increased [76], similar to observations in primary biliary cirrhosis. A specific autoantibody in collagenous colitis has not been reported.

Bile acids

Data on bile acid malabsorption in microscopic colitis are conflicting. In one study no association was found [77], whereas others found bile acid malabsorption in 27–44% of patients with collagenous colitis and in 9–60% of patients with lymphocytic colitis [78–80]. The coexistence of bile acid malabsorption seems to worsen the diarrhea in patients with collagenous colitis [78]. These observations are the rationale for recommendations of bile acid binding treatment, which was reported effective in a majority of patients with microscopic colitis and concomitant bile acid malabsorption [78, 80]. Even patients without bile acid malabsorption may respond to this treatment. This emphasises the possibility of a causative agent in the fecal stream, and the therapeutic effect may possibly be related to binding of luminal toxins [81].

Nitric oxide

Colonic nitric oxide (NO) production is greatly increased in active microscopic colitis caused by an up-regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in the colonic epithelium [82–84]. The levels of NO correlated with clinical activity and histopathologic status of the colonic mucosa; i.e. patients in histopathologic remission had normal levels of colonic NO in contrast to increased levels in patients with histologic active disease [84, 85]. The role of NO in microscopic colitis is uncertain. NO is an inflammatory mediator but whether its role is proinflammatory or protective remains unclear. Nitric oxide may furthermore be involved in the diarrheal pathophysiology as infusion in the colon of NG-monomethyl-L-arginine, an inhibitor of NOS, reduced colonic net secretion by 70% and the addition of L-arginine increased colonic net secretion by 50% [86].

Secretory or osmotic diarrhea

Diarrheal pathophysiology in collagenous colitis has been regarded as secretory, caused by the epithelial lesions, the inflammatory infiltrate in the lamina propria and the collagenous band that may be a barrier for reabsorption of electrolytes and water [46, 87]. Furthermore, an impaired epithelial barrier function due to down-regulation of tight junction molecules was found to contribute to diarrheal pathophysiology [46]. Studies on the influence of fasting on diarrhea in collagenous colitis indicated, however, that osmotic diarrhea was predominant [88]. Many patients report that fasting reduces their diarrhea in accordance with this observation.

Clinical features and diagnosis

The main symptom in collagenous colitis is non-bloody diarrhea that may be accompanied by nocturnal diarrhea, fecal incontinence, crampy abdominal pain and distension [10]. Weight loss of up to 5 kg is common initially and occasionally is even more pronounced. Serious dehydration is rare, although 25% of patients report 10 or more daily stools, and stool volumes up to 5 litres have been reported. Mucus or blood in the stools is unusual. In some patients the onset of the disease may be as sudden as that of infectious diarrhea [10].

In most cases the clinical course is chronic, relapsing and benign [89, 90]. Serious complications are uncommon, although a number of patients with colonic perforation have been reported [91-94], and perforation seems to be related to “mucosal tears” that can be seen at colonoscopy [95–98]. The risk of developing colorectal cancer in collagenous colitis is not increased [89,99]. In a follow-up study, 63% of patients had lasting remission after 3.5 years [100]. Another cohort study showed that all patients were improved 47 months after the diagnosis and only 29% of these required medications [101]. In a number of collagenous colitis patients, however, remission is difficult to achieve, and such patients have usually tried different medications unsuccessfully [10, 43].

Patients with collagenous colitis often have concomitant diseases. Up to 40% have one or more associated autoimmune diseases. The most common are rheumatoid arthritis, thyroid disorders, celiac disease, asthma/allergy and diabetes mellitus. Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis concomitant with collagenous colitis have occasionally been reported [10,102]. Lymphocytic colitis is clinically indistinguishable from collagenous colitis and the predominant symptom is chronic watery diarrhea. In a recent report, however, it was found that symptoms in lymphocytic colitis were milder and more likely to disappear than in collagenous colitis [59]. Similar to collagenous colitis, lymphocytic colitis has also been reported in association with autoimmune diseases [59]. The prognosis of lymphocytic colitis is good [103]. There is no increased mortality and no increased risk of subsequent bowel malignancy reported. A benign course was reported in 27 cases with resolution of diarrhea and normalization of histology in over 80% of the patients within 38 months [104]. Others reported that the clinical course was a single attack in 63% of the patients with a median duration of six months from onset of symptoms to remission [12].

Only microscopic assessment of colonic mucosal biopsies can verify the diagnosis of collagenous or lymphocytic colitis. Merely non-specific, minor laboratory abnormalities are found, and there are at present no blood tests available for screening purposes. Analyses of P-ANCA [76] or serum procollagen III propeptide are of no diagnostic value in collagenous colitis [105]. Stool examinations reveal no pathologic organisms though increased excretion of fecal leukocytes in more than half of the collagenous colitis patients has been reported [26]. Barium enema and endos-copy are usually normal, though subtle endoscopic changes such as mucosal edema, granularity or erythema may be seen in up to 30% of cases [10, 12]. Pancolonoscopy must be preferred to sigmoidoscopy as the thickened collagenous layer in collagenous colitis may be absent in a considerable percentage of rectal biopsy specimens [18]. The use of confocal laser endomicroscopy may aid in diagnosing collagenous colitis [106,107].

One or two diseases?

It has been questioned whether lymphocytic colitis and collagenous colitis are the same disease in different stages of development or two different but related conditions, as they have a similar clinical expression and similar his-topathologic features, except for the subepithelial collagenous layer in collagenous colitis. Conversion of lymphocytic colitis to collagenous colitis or the opposite has been reported [7, 108], but the fact that conversion happens fairly seldom, and differences in sex ratio and HLA pattern [38] makes it more likely that collagenous colitis and lymphocytic colitis are two separate but related entities.

Treatment of microscopic colitis

The enigmatic etiology of microscopic colitis has led to a wide range of anti-diarrheal and anti-inflammatory drugs being evaluated for medical treatment. A relatively small number of controlled trials has been conducted, and recommendations on therapy have mainly been based on retrospective reports and uncontrolled data [10, 109]. The benign course of microscopic colitis in general has led to suggestions of an algorithm with a “step-up” type of approach to medical treatment, depending on clinical response and outcome in the individual patient. Milder symptoms may be well controlled using drugs such as loperamide or cholestyramine [78, 110]. However, in patients with moderate to intense symptoms potent anti-inflammatory treatment is required. In a retrospective study, the degree of lamina propria inflammation in colonic biopsies was found to predict the response to therapy, and greater inflammation may indicate the need for corticoster-oid therapy [56]. A finding of a substantial degree of inflammation at the time of diagnosis may thus aid in clinical decision-making.

Randomised controlled trials

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree