Fig. 1 a, b

Passive and active structures of the pelvic floor. a Pelvis with organs and muscles (muscles are shaded with striations). b The corresponding sagitall T2-weighted turbo spin-echo magnetic resonance images of pelvic organs, pelvic floor muscles, perineal body, and anococcygeal ligaments

Passive Support Structures

These structures comprise:

Pelvic bones

Supportive connective tissue of the pelvis, which consists of ligaments and endopelvic fascia.

Active Support Structures

These structures comprise:

Pelvic floor muscles

Neurologic wiring that results in sustained (tonic) and intermittent voluntary muscle contractions during activity.

Integrated Multilayer System

These passive and active components of the pelvic floor function as an integrated multilayer system that comprises four principle layers (Fig. 2). From cranial to caudal, it consists of:

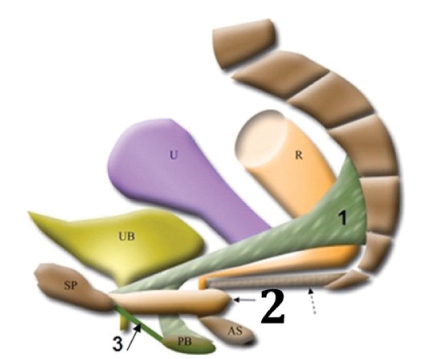

Fig. 2

Three-dimensional schematic drawing of the component of the pelvic floor integrated into a multilayer system, from cranial to caudal, consisting of: 1 endopelvic fascia, giving support to the uterus and upper vagina; 2 pelvic diaphragm, including the puborectalis (solid arrows) and iliococcygeus (dashed arrow); 3 urogenital diaphragm. AS anal sphincter complex, PB perineal body, R rectum, SP symphysis pubis, U uterus, UB urinary bladder. Reproduced from [7]

Pelvic diaphragm

Perineal membrane (urogenital diaphragm)

Layer of superficial muscles comprising the external genital muscles

Supportive Connective Tissue of the Endopelvic Fascia and Related Structures

Level I (Suspension)

The portion of the vagina adjacent to the cervix (cephalic 2–3 cm of the vagina) is suspended from above by the relatively long connective tissue fibers of the upper paracolpium.

Level II (Attachment)

In the midportion of the vagina, the paracolpium become shorter and attaches the vaginal wall more directly to the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis at the lateral pelvic wall. This attachment stretches the vagina transversely between the bladder and rectum and has functional significance; the structural layer that supports the bladder (the pubocervical fascia) is composed of the anterior vaginal wall and its attachment through the endopelvic fascia to the pelvic wall.

Level III (Fusion)

Near the introitus, the vagina is fused laterally to the levator ani and posteriorly to the perineal body, whereas anteriorly it blends with the urethra. At this level, which corresponds to the region of the vagina that extends from the introitus to 2–3 cm above the hymenal ring, there is no intervening paracolpium between the vagina and its adjacent structures, contrary to the situation at levels I and II.

Pelvic Diaphragm

The pelvic diaphragm acts as a shelf supporting the pelvic organs and includes:

Levator Ani Muscle

This muscle consists of the puborectalis and iliococcygeus.

Coccygeus Muscle

It arises from the tip of the ischial spine, along the posterior margin of the internal obturator muscle. The fibers fan out and insert into the lateral side of the coccyx and the lowest part of the sacrum. This shelf-like musculotendinous structure forms the posterior part of the pelvic diaphragm.

Urogenital Diaphragm

The urogenital diaphragm, or perineal membrane, is a fibromuscular layer directly below the pelvic diaphragm.

Classically, it is described as a trilaminar structure, with the deep transverse perineal muscle sandwiched between the superior and inferior fascia.

Superficial Muscle Layer

This layer comprises the external genital muscles. At the most superficial of the four layers of pelvic floor lay the external genital muscles, comprising:

Superficial transverse perinei

Bulbospongiosus

Ischiocavernosus.

Pathophysiology of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

Urinary Incontinence

Definition and Classification

As classified by the International Continence Society (ICS), UI of all types is defined as involuntary loss of urine that is both objectively demonstrable and socially or hygienically problematic for the patient [9, 10].

Common subtypes of UI include SUI, urge urinary incontinence (UUI), and mixed urinary incontinence (MUI).

Symptom of SUI is involuntary leakage on effort, whereas the symptom of UUI is involuntary leakage accompanied by or immediately preceded by urgency. MUI is a combination of SUI and UUI [11].

SUI is the most common type of incontinence in women, with 86% of incontinent women presenting with the symptoms of either pure (50%) or mixed (36%) forms of SUI [10].

Pathophysiology of Urinary Incontinence

UI is a multifaceted problem. It may be:

Extraurethral, caused by urinary fistula or an ectopic ureter

Urethral, caused by bladder abnormalities or sphincteric abnormalities. Urethral incontinence can be divided into:

Urethral incontinence because of abnormal detrusor function (UUI)

Urethral incontinence because of urethral abnormalities (SUI).

Pathophysiology of Stress Urinary Incontinence

There are also several different types of SUI [11]:

Because of poor urethral support (most common type)

Despite normal urethral support, because of defective sphincteric function of the vesical neck and urethra (less common type).

Damage to the Elements of the Urethral Support System

This could occur because of urethral trauma, resulting from childbearing. Other common causes include:

Menopause

Medical conditions that increase intra-abdominal pressure

Persistent heavy lifting or straining

Neurologic damage

Connective tissue disorders.

Damage to the External Sphincter

Damage to this system can be associated with the development of SUI. Any of the urethral sphincteric components may be diminished by:

Loss of estrogen

Surgical trauma

Childbearing

Drugs that alter muscular tone

Vascular changes

Local damage.

Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Definitions and Classification

The term prolapse is commonly used to describe any degree of downward pelvic organ movement, including anterior vaginal prolapse (cystocele), apical or uterine prolapse, and posterior vaginal prolapse, which includes enterocele, rectocele, and perineal descent but does not include rectal prolapse.

Pathophysiology of Pelvic Organ Prolapse

POP has been attributed both to (1) damage to the levator ani muscle [12] (where weakness of the levator ani may cause widening of the levator hiatus and descent of the central portion of the pelvic diaphragm), and (2) an endopelvic fascial defect [13]. However, DeLancey [14, 15] described the interaction between pelvic floor muscles and endopelvic fascia and maintained that it is not possible to determine which is responsible for prolapse — damage to muscle or damage to fascia — because these two aspects of pelvic support are intimately interdependent.

Factors Contributing to Pelvic Organ Prolapse

The following factors contribute to POP [12–15]:

Childbirth: vaginal childbirth can contribute to POP by either of two mechanisms:

Direct damage to the endopelvic fascial support system and walls of the vagina

Direct and indirect damage to the muscles and nerves of the pelvic floor.

Connective tissue: the protein collagen is responsible for the strength of the pelvic connective tissue. Most clinicians believe that defective endopelvic connective tissue weakens the pelvic support system and hence contributes to POP.

Pelvic neuropathies: some evidence links vaginal childbirth with pelvic neuropathies and POP. When there is denervation of the pelvic floor muscles, there may be progressive descent of the pelvic diaphragm, followed by pelvic organ descent.

Anal incontinence: the prevalence of fecal incontinence may be as high as 17% in patients with UI and prolapse. Fecal incontinence is complex in causation, and radiologists should not oversimplify the etiology by just concentrating on mechanical damage to the sphincter.

Other factors include:

Chronic and repetitive increase in intra-abdominal pressure

Chronic respiratory conditions associated with forceful and repetitive coughing.

Anorectal Dysfunction

Anorectal dysfunction may be divided into two main categories: anal incontinence and constipation.

Anal Incontinence

Definitions and Classification

Anal incontinence is a common disorder and is defined as the involuntary loss of flatus, liquid, or solid stool, causing social and hygiene problems.

The prevalence of some degree of fecal incontinence in the general population is about 2%, rising to 7% in the elderly [16].

Pathophysiology

Overall, about 5% of the population has anal incontinence, which can develop at any age. Many factors must work in concert to achieve continence. These factors include:

Rectal:

Stool delivery: adequate consistency and volume

Rectal function: compliance, sensation, contractility

Anorectal responses: rectoanal inhibitory reflex and anal sampling.

Anal sphincters:

Intact sphincters

Good sphincter functions and muscle bulk

Coordinated contraction.

There are many causes of incontinence that may act independently or in conjunction to compromise continence. Disorders of these components may be:

Neuropathic: Autonomic neuropathy is commonly associated with disorders of rectal motor complexes; there may be high-pressure contractions that exceed sphincter tone or the absence of compensatory increases of tone in the sphincter.

Idiopathic: Incontinence in this case is usually associated with a patulous anal sphincter and passive stretching of the puborectalis muscles.

Structural: Structural abnormality of and damage to continence components are confined to the anal sphincter or occur higher in the digestive track.

Clinical Assessment and Investigation

Clinically, fecal leakage can be divided into two categories [16]:

Minor, when there is just staining of underwear or bedding

Major, when there is definite soiling considered to be a problem by the patient.

Fecal incontinence may be divided into passive, urge, and nocturnal incontinence:

Passive: leakage is the main problem; stool passage occurs without patient awareness. This type of incontinence is most likely to be due to internal anal sphincter damage.

Urge: stool cannot be held back despite attempts to inhibit defecation. This type of incontinence is most likely to be due to external sphincter damage.

Nocturnal incontinence: this type suggests a neurologic causation.

Constipation

Definitions and Classification

It should be borne in mind that the term constipation describes a symptom — an expression of a sensation rather than a clinical sign — and is particularly subjective, meaning different things to different people. When patients are asked to define constipation, there is considerable individual variation in response. Some concentrate on frequency of bowel movements; others focus on ease of defecation and stool size and consistency.

It is generally accepted that a satisfactory definition of constipation must include the concepts of both infrequent defecation and difficult evacuation [17]:

Infrequent defecation is usually defined as bowel movements that occur three or fewer per week and is most likely associated with slow transit time

Difficult evacuation is defined as straining during stool passage that accounts for more than 25% of the time spent in the lavatory. Its presence indicates obstructed defecation.

Pathophysiology of Obstructed Dysfunction

Broadly, there are two major types of constipation [17]:

Slow-transit type (infrequent evacuation), in which the movement of fecal material through the colon is slow

Outlet obstruction, in which evacuating rectal contents requires prolonged straining during stool passage.

Slow Colonic Transit Time

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree