Fig. 1.1

Theodor Billroth (1887)

In the autumn of 2014, studying historical connections in the field of gastric cancer therapy led to a deepened understanding of therapeutic concepts comprising a time span of more than 130 years.

Widely different measures of cancer therapy used in the course of decades have been evaluated in numerous studies. By surveying different treatment strategies over such a long stretch of time, some committed physicians/scientists may feel inspired to develop new ideas and concepts of treatment [2].

Taking a present-day view on past failures of studies can help draw vital conclusions for today’s work and make for reassuring motivation.

There is an additional opportunity to be found in studying the history of various therapeutic procedures: a decisive detail may have simply been overlooked until today.

Decades of Surgery Development

The idea to perform a stomach resection because of a carcinoma of the pylorus was developed by Dr. John Jones, the first professor of surgery at King’s College, and a cofounder of the New York Hospital. Jones wrote the first American textbook on surgery in 1775. Around 1800, influenced by the painful death of a friend due to a carcinoma of the pylorus, Jones performed resections of the pylorus on dogs and rabbits, however without success.

Time had not come yet for that kind of surgery in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. For tackling the problems of gastric surgery, three preconditions had first to be resolved: (1) the sero-serose suture technique (Lembert 1826), (2) antiseptic wound therapy (Semmelweis 1847, Lister 1867) and (3) pain treatment during such time-consuming operations (Jackson 1841, Morton 1846).

In 1874, it was Professor Billroth who instructed his assistants Gussenbauer und Winiwarter to develop a surgery technique in dogs for prospective stomach resection in humans. Gussenbauer developed the anastomosis of both lumina with a Lembert suture line. However, out of seven dogs only two survived: two of them died after anastomotic leakage; one after contact infection; and two more from ileus.

In the course of these experiments on animals, some problems were successfully resolved: First, the assistant surgeons could demonstrate that in five out of seven dogs the suture lines were not destroyed by stomach fluid; second, that the serosa between stomach and duodenum healed neatly; third, that the ligature of the vessels along the smaller and greater curvature of the stomach did not lead to necrosis of the stomach in situ.

Gussenbauer and Winiwater also demonstrated that the two surviving dogs were able to eat and ingest food like healthy ones and, moreover, exhibited after rehabilitation no difference of behavior compared to healthy dogs. Eight months after surgery the sections of the two surviving dogs displayed in both an open anastomosis; however, one dog had a peptic ulcer at the anastomosis.

Parallel to the animal research studies, Gussenbauer and Winiwarter studied the pathology reports of patients who died from carcinoma of the pylorus between 1817 and 1873. This retrospective analysis revealed that 41.1 % (223/542) of the patients with carcinoma of the pylorus had not developed metastases but died because of tumor cachexia due to stenosis of the pylorus.

Another fact of considerable practical dimension was revealed by Gussenbauer. He detected that in 32 % of patients (172/542) the tumor was not fixed, but mobile. These results were to prove that a number of patients could be cured by the resection of the tumorous pyloric/antrum region.

Summarizing the results of the animal studies and the retrospective clinical investigations, Gussenbauer followed that “… for the treatment of stomach cancer , which is located usually at the pylorus region and leads due to local stenosis and its consequences not seldom to death, partial stomach resection should be taken into account” [1].

In 1879, Billroth reported at a surgeons’ meeting that after successful treatment of an incarcerated femoral hernia with over-suturing the small bowel as well as the successful over-suturing of the stomach wall after a penetration accident time had come for surgeons to go about performing a partial stomach resection and not to fear that stomach fluids would prevent sanatio per primam. Two contemporaries of Billroth’s tried to perform stomach resections: surgeon Péan on April 9, 1879, in Paris; Rydygier in Chelmno, Poland, on November 16, 1880. Both of them failed.

Billroth was to wait for another 5 years before the right patient for a pylorus resection entered General Hospital, AKH, in Vienna. The difficulties in finding the right patients were also due to the fact that X-ray was not yet available for diagnosing such lesions. Diagnoses had to be done by a thorough clinical history and investigation of a palpable tumor.

On January 25, 1881, a 43-year-old Viennese, Therese Heller, was sent to Billroth’s clinic at AKH, General Hospital. She had been suffering from typical symptoms of a pylorus stenosis for 3.5 months. Clinical investigation showed that she had on the right side of the umbilicus a fist-sized tumor that was still mobile. Although the patient was very weak, Billroth decided nonetheless to perform a pylorus resection, an operation which had been painstakingly planned by him before.

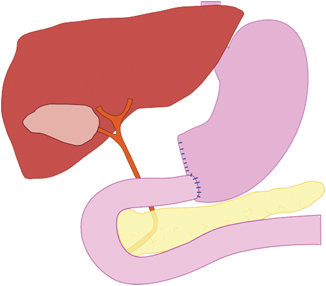

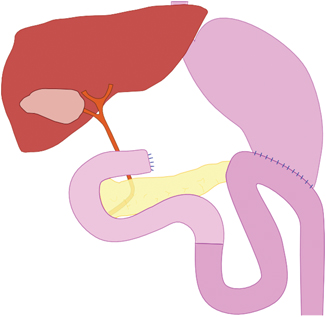

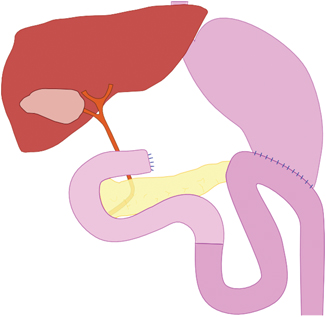

The Billroth I operation (Fig. 1.2) in chloroform anesthesia took 1.5 h. The next morning the patient only felt a little pain in the stomach region, the heart rate was 110, and she was running a temperature of 39 °C late evening. There was no change during the following 3 days. On day 4 after surgery the patient began to eat some mushy food, which agreed with her.

Fig. 1.2

Billroth I-gastric resection

The histology report showed a partial stomach with a length of the greater curvature of 14.5 cm and a diameter of the lesser curvature of 10 cm. There was also a 2-cm margin of healthy duodenum on the stomach. There were two tumor-infiltrated lymph nodes on the greater curvature. Microscopically, the tumor was a gelatinous carcinoma, infiltrating the subperitoneal layer.

On day 6 after the operation the wound dressing was changed for the first time. The wound healing was per primam and some sutures were removed. The remaining sutures were removed the next day. Miss Therese Heller started to eat and gained energy over the following week. She wished to be discharged from hospital when she was able to eat different meat dishes with appetite on postoperative day 22. During the following weeks her sacral decubitus was healing well.

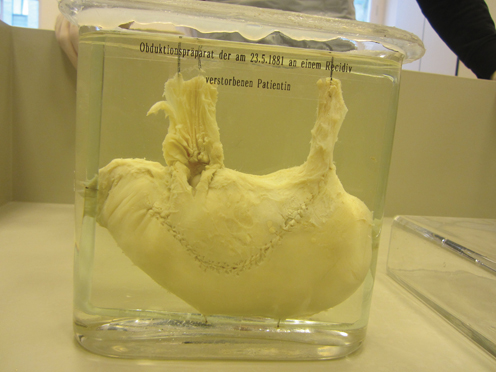

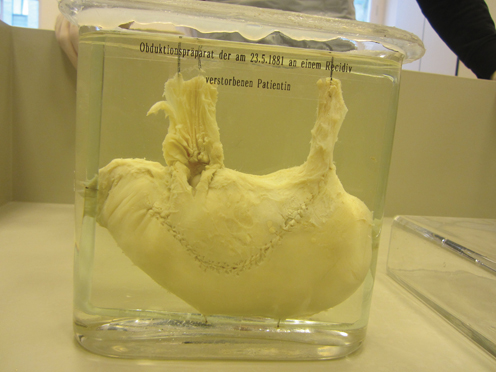

Until March 3 the patient was under regular control by her general practitioner. She was continuously improving and ate whatever she felt like. However, by end of April, Therese Heller suffered a relapse, and quite soon it was obvious that she developed a recurrence of the cancer. She died on May 23, 1881, in Billroth’s clinic at the General Hospital of Vienna (Fig. 1.3).

Fig. 1.3

“Post mortem of stomach of the patient with the first successful gastric resection by Billroth on January 25, 1881, who died on May 23, 1881, suffering from a relapse.” Museum for medical history in Vienna, Währinger Straße 25, 1090 Wien

At a surgeons’ meeting in Vienna on February 25, 1881, Billroth reported about his patient Therese Heller and the first gastric resection. In this lecture, Billroth summarized the following facts:

1.

The resection of the antrum and further parts of the stomach has no influence on the digestion of the patient.

2.

The ingestion of the suture material at the anastomosis is not a problem, had so far not occurred in this patient and had not been a problem for another patient on whom he performed a closure of a stomach fistula 3 years before.

3.

Billroth expected a somewhat narrowing of the anastomosis; however, without any clinical consequences for the patient since he never experienced such problem in patients with small bowel resection.

4.

A recurrence of the carcinoma in the patient, Therese Heller, is to be expected since the adhesions he saw during the operation might come from tumor cells.

Billroth closed his lecture in saying: “At this stage we should be content that it is possible to perform a gastric resection with success. I just can assure you that Mrs. Therese Heller has been feeling much better since the first postoperative day; she has not been in pain and has had no vomiting attacks any more.”

Further Resection Methods

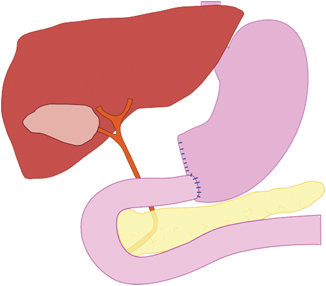

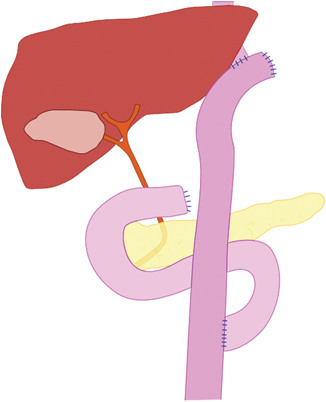

Consecutively, Billroth developed a second resection method in 1885. Duodenum and stomach were closed blind after pylorus resection and a new connection between the stomach rest and jejunum was created. By doing this, he used anterior gastro-enterostomy, but understood carrying out Billroth II operation (Fig. 1.4) as a kind of stopgap operation [3], the reason being the passage irritations (circulus vitiosus) that occurred during the anterior/front gastro-duodenostomy.

Fig. 1.4

Billroth II-gastric resection

Kocher demanded that after the excision of the gastric carcinoma the stomach had to be closed at all events, followed by a gastro-enterostomy. He blind stitched the stomach and implanted the duodenum posterior into the stomach wall. He therefore held the view that the kind of complications occasionally observed concerning gastro-enterostomy (Billroth, method II) could be safely avoided and satisfactory results could be achieved. Nonetheless, both his method and Billroth’s method I shared the same disadvantage of being only performable if the suture line of duodenum and stomach rest was tension free [4].

After this first successful resection of part of the stomach, Billroth I method, it was Connor who tried first in Cincinnati to treat a 50-year-old woman’s extensive gastric carcinoma by a total stomach extirpation in 1883. It was worldwide the first ever gastrectomy performed on a human being. Unfortunately, the patient died while being operated upon [5].

In 1897, Swiss surgeon Schlatter had a brilliant idea: the first ever esophago-enterostomy after gastrectomy. The beginning of numerous consecutive variants of surgeries following the example of gastrectomy. Schlatter pulled a small bowel loop antecolically towards the lumen of the esophagus and connected them—after a longitudinal section of about 1.5 cm on the small intestine—by running circular sutures.

His patient gained 8.5 kg within 9 months but died 14 months after the operation on a recurrence [6]. Despite the fact that a tiny part of the stomach was detected during section, this case provided evidence that a human being can live without a stomach.

In 1898, a year after Schlatter’s first total resection, MacDonald successfully carried out a gastrectomy on a 38-year-old patient who was able to leave hospital on day 13 after complication-free progress. The patient’s survival span is not known. The same year Brigham was third in line to successfully perform a gastrectomy. He managed to create an anastomosis between esophagus and duodenum on a 66-year-old woman. She survived for 2 more years.

In principle, gastric cancer surgery cannot be understood as a standard method in its first phase when the focus was still on researching and ongoing development of methods. More generally, it can be stated that gastro-enterostomy and pylorus resection were given approximately the same attention and priority over gastro-enterostomy, in particular during the early period before 1900.

The innumerous variants of gastro-enterostomy—not all of them can be mentioned here—speak of the importance attached to this operation at the turn of the nineteenth century. This is also due to the fact that the majority of patients did not become symptomatic before an advanced stage and only then consulted a doctor. There was general awareness of the fact that excision of the carcinoma, namely resection methods as, e.g., pylorus resection, constituted the only prospect of cure [7].

Then and there, gastrectomy was playing a rather subordinate role. Although it was successfully carried out by known surgeons, it was not popular with the broad mass of surgeons at the beginning of the twentieth century because of the inherent technical difficulties. Occasionally, voices were raised that there was in all probability no future in stomach extirpation [8].

Finney and Rienhoff counted 122 cases from the years 1884 to 1929 of stomach extirpation because of gastric carcinoma mentioned in the literature. Only 67 cases were considered genuine “total gastrectomy,” namely those where a total resection of the stomach including cardia and pylorus could be assumed.

Finney’s and Rienhoff’s data compilation shows that in keeping a part of the stomach—whatever size—reduced the hazards of operation drastically. Direct comparison with the group of total resections yielded a 28.8 % decrease of mortality rate [9].

Causes of Death

When interpreting causes of death , anesthesia must be taken into account. Anesthesia was then at a fairly young age of about 50—not yet fully mature—and therefore certainly the cause of many surgical incidents. Moreover, although the term “asepsis” had been known since 1847, antiseptic measures were not as strict as today. It was a general practice to operate with bare hands on patients—at least before 1890, when Halsted introduced rubber gloves. Face mask and surgical coat became even later part of surgeons’ work wear.

Despite relative inexperience in matters of hygiene and anesthesia, peritonitis and shock took first places as causes of death. These two were caused, among other things, by technical deficiencies. Most surgeons used the running two-row suture for anastomoses, but suture insufficiency was extremely problematic to handle [10].

Another frequent cause of death was pneumonia, often in combination with pulmonary gangrene [11]. The longer an operation took, the greater was the hazard of pneumonia.

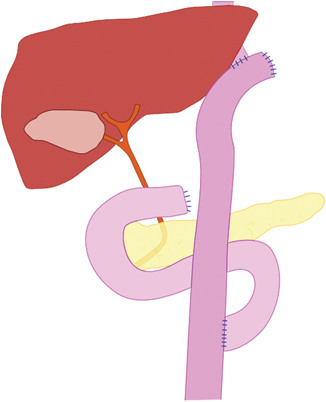

The great number of publications on gastrectomy and its reconstruction potential in the 1940s and 1950s of the past century provide evidence of how intensively the topic was being dealt with then and there. Roux introduced as early as 1907 the end-to-side anastomosis of the afferent loop (Fig. 1.5). After occluding the duodenal stump, he skeletonized a jejunal segment (about 20–30 cm aboral of the flexura duodenojejunalis) and cut the intestinal tube through. Then the aboral small intestine was taken up retrocolically to the esophagus and anastomosed with the latter. Safeguarding the suture was achieved by a simple segmental jejuniplication. The small intestinal tube was closed by means of terminal–lateral anastomosis below the transverse colon [12].

Fig. 1.5

Y-Roux reconstruction after gastrectomy, developed in 1907

In 1952, Hunt combined Roux’s loop building with pouch reconstruction, an attempt to prevent reflux into the esophagus. After gastric resection he occluded the duodenal stump blind and severed the jejunum approximately 30–35 cm below the Treitzsch ligament. Then he pushed the distal branch antecolically up towards the esophagus and formed from its end a kind of loop that was anastomosed at a length of approximately 15 cm side-to-side. This procedure yielded a kind of tube that was connected end-to-side with the esophagus. Finally, the proximal jejunum was anastomosed laterally to the distal jejunum [13].

In 1952, Longmire seized upon Seo’s idea of interposition of a short segment of the small intestine between esophagus and duodenal stump. He isolated a segment of approximately 10–15 cm from the upper jejunum, preserving its nutritive vessels, anastomosed the two jejunal lumina and positioned the jejunal segment between esophagus and duodenum. All three anastomoses were end-to-end connections [14].

On the basis of a collective statistic of different specialist surgeons, Pack and McNeer highlighted the frequency distribution of surgical procedures concerning passage reconstruction after gastrectomy. From 1884 till 1942 esophago—jejunostomy was continually gaining ground as the surgical method of choice: between 1884 and 1920 it was at least equivalent to the esophago–duodenostomy; between 1921 and 1930 with a rate of 64.9 % it was deployed more than double as much as the other; from 1931 till 1942 esophago–jejunostomy reached 95.1 %—and was thus the absolute lead [15].

Steingräber compiled from 36 authors’ reports 219 fatalities after gastrectomy between 1927 and 1952 [16]. During this period, peritonitis ranked first as the cause of death. Frequently technical deficiencies were to blame for this, in particular, caused by insufficiency of esophageal anastomosis [17].

Acceptance concerning gastrectomy was continually gaining importance after 1940, beating subtotal stomach resection to second place as the curative resection method of choice. At that time, preference was given to extended gastrectomy, accompanied by additional resections of the omentum as well as distal pancreas and spleen .

Out of a total of 287 patients, treated at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Center, New York, 263, i.e., 91.6 % could be operated on; 112 of these underwent curative resection (39 %). Between 1951 and 1954 the 5-year survival rate of the patients who were curatively resected was 23.2 % for all patients and 26.8 % for the 40 patients who survived surgery. In comparison, the 5-year survival rate of patients treated between 1931 and 1950 was 21.6 %—not much of a difference—although expanded gastrectomy was deployed more frequently in comparison between 1951 and 1954 [18].

Subtotal Gastric Resection or Gastrectomy?—Indications

Holle and Heinrich published an attempt at establishing criteria for an indication of whether to choose partial or total resection in 1960 [19]. So as to facilitate decisions for the appropriate measures to be taken, Holle and Heinrich classified cases as different groups (A, B, C):

A-case: tumors that were confined to the stomach and had not yet developed visible or palpable metastases in the regional lymph nodes belonged to this group. According to the authors, partial resection was in general in line for such cases if the demand for radical removal could be fulfilled.

B-case: Bigger, still movable tumors confined to the stomach but with visible metastases in one or two lymph drainage areas were subsumed in this group. Holle and Heinrich recommended for this group total resection followed by small intestine interposition according to Longmire.

C-case: This group comprises advanced cases. The tumor had transgressed the stomach borders in at least one direction and developed regional metastases, or even distant metastases. Here, the sole purpose of surgery was to provide palliative measures for pain relief.

The authors held the opinion that in the wake of decreasing surgery fatalities in connection with total gastrectomy (then 10 %; in some places as low as 3–4 %) the administration of total gastrectomy for the B-cases was justifiable. Surgery mortality did not differ much from partial resection, which was sufficient reason to prefer total gastrectomy. After all, the principle of radical surgery had been long around for cancers of other organs. Primary mortality rates of up to 50 % connected to total gastrectomy had so far been an indicator against taking radical measures.

The Role of Lymph Node Dissection

In the early 1940s, Coller, Kay, and McIntyre published a study of all regional lymph nodes—a veritable eye-opener for many surgeons [20]. Forty out of 53 cases of gastric carcinoma showed positive lymph node involvement. According to their findings, the most frequently involved lymph node groups were the “inferior gastric-subpyloric” and the “superior-gastric” lymph nodes.

There was neither a relationship between the duration of symptoms and the occurrence of lymph node metastases, nor a relationship between tumor size and the existence of lymph node metastases detectable. However, what they were able to point out was that the probability of metastasis in the regional lymph nodes increased with the depth of tumor cell infiltration in the stomach wall. Metastasis was provable even for the majority of cases where regional lymph nodes were either not palpable or, if palpable, considered nonsuspect by surgeons. This explains why the authors recommended including the 4 lymph node zones into the resection—irrespective of whether lymph nodes were palpable or not—for the sake of better chances of cure.

Between November 1950 and January 1953, Sunderland et al. also carried out a study on lymph node metastasis connected to gastric cancer—similar to the one conducted by Coller et al. 10 years before [20]. Based on 41 preparations investigated, the authors arrived at the following conclusions:

Lymph node metastasis had occurred in 85 % of the cases

Tumors of the proximal third of the stomach metastasized preferentially in the superior, paracardial and pancreatico-lienal lymph node groups; tumors of the distal third showed frequently metastasis in the superior, subpyloric and inferior lymph node groups; tumors of the medium third, as well as such that involved the whole, metastasized at similar rates in all regional lymph node groups.

In case the gastric carcinoma was located in the proximal or medium third, more lymph node metastases were found; the highest quantity of lymph node metastases were diagnosable when the tumor had involved the whole stomach.

Depth of tumor (cell) infiltration appeared to have a crucial influence on the amount of lymph node metastases .

Remine and Priestley investigated the relation between localization of infiltrated lymph nodes and reported their results in 1953.

What struck them was the fact that with the group of 5-year survivors only 6 % had subpyloric lymph node metastases. While the group of earlier fatalities showed 71 % subpyloric lymph node metastases .

Laurén—Classification of Gastric Carcinoma

Classification according to Laurén differentiates on the basis of morphological criteria between two types of gastric carcinoma :

Intestinal type, which is sharply demarcated against the environs. This type creates glands of cylindrical epithelium (cells) that resemble intestinal epithelium and produce mucus.

Diffuse type, de-differentiated adenocarcinoma with considerable cell dissociation or else “ signet ring cell” carcinoma, which are but diffusely demarcated against the environs [21].

“Gastrectomy totale de principe”

French surgeons Lefèvre and Lortat-Jacob demanded in 1950 “gastrectomie totale de principe,” based on the principle that —whatever gastric carcinoma was concerned—gastrectomy was to be carried out as principle gastrectomy. This demand contradicted the view held by many surgeons that “gastrectomie totale de nécessité” should only be performed in case of total involvement of the stomach. They had many followers but also met with opponents [22]. Lefèvre and Lortat-Jacob argued that their demand was corroborated by the respective literature that certified lower rates of fatalities after gastrectomy [23, 24]. Their fundamental idea was one of decreasing the number of local recurrences by heightened radicalness—and thus achieve better survival rates [25].

“Gastrectomy de nécessité”

Proponents of gastrectomy “de nécessité” held the opinion that there existed no such procedure like a “standard procedure” because gastric carcinoma as such did not exist either. In their view, there were various different pathological–histological and clinical forms of gastric carcinoma that necessitated individualized, stage-oriented treatment [26, 27].

Next to preoperative staging, knowledge of the histological-morphology of the gastric carcinoma (ever since Laurén introduced histological tumor classification) was playing an increasingly significant role, when it came to choosing the appropriate method of therapy.

Knowledge of the tumor type, gathered from different observations on tumor sectates and the expansion of the tumor depending on its type—was to determine the method of therapy. Whereas the intestinal type and the diffuse type, that was restricted to mucosa and sub-mucosa, expanded only a few millimeter beyond the tumor limits macroscopically discernible, the diffuse, advanced carcinoma behaved differently: although the tumor wall showed macroscopically no pathological findings, tumor cell clusters were histologically discernible even several centimeters away from the macroscopic tumor border [28].

Therefore, oral and aboral safety zones were devised to do justice to the different histological-morphological diagnoses according to Laurén. Although the primary tumor was resected, keeping to the necessary safety zone, lymph nodes without pathological findings were not resected. It was self-understood that for tumors of the upper third of the stomach, as well as of diffuse type tumors of all sections of the stomach, gastrectomy was the method of choice in order to keep to the peri-tumoral safety zones [29].

Gastrectomy “de principe” was only opposed in cases of gastric carcinoma of the distal third and certain carcinoma of the medial third, of the intestinal type [30]. Main arguments against gastrectomy “de principe” were higher surgery fatality and a falling-off quality of life . Better life quality could be achieved by leaving the rest of the stomach [31].

What arises from the compilation of studies is the fact that even today gastrectomy is accompanied by complication rates about 10–15 % higher in comparison to subtotal stomach resection.

Indication Concerning Gastrectomy, Respectively, Subtotal Stomach Resection

According to guidelines for multi-modal therapy of gastric carcinoma, decreed in 1995 by three task groups of the Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft (German Cancer Association), therapy by surgery necessitates keeping an adequate safety zone of 5 cm, respectively, 8 cm in situ.

Decision making for either gastrectomy or else subtotal resection depends on tumor localization, histological–morphological type and individual assessment of risk. As a rule, the diffuse type requires gastrectomy. As long as an oral safety zone of 5 cm can be warranted, subtotal resection and gastrectomy for carcinoma of the intestinal type in the distal and medial thirds of the stomach appear to be of the same value [32] .

Quality of Life After Stomach Resection

Surgery fatality, morbidity, and 5-year survival rates are the decisive factors of prognosis after surgical treatment of gastric cancer. As technical problems have been solved by and large in recent years and fatality and morbidity, also with gastrectomy, have been going down to values that can hardly be changed, the focus is now on yet another criterion of judgment when looking for an appropriate method of treatment: postoperative quality of life . Surgeons have to aim at making the potentially short span of life remaining as bearable as possible for the patient. So far, there is no standardized definition of “quality of life” available, since the term embraces ever so many aspects to be considered when trying out different methods of measurement [33].

Subtotal Gastric Resection Versus Gastrectomy

Meanwhile, in the case of curative resection, subtotal stomach resection and gastrectomy—allowing for the principles of radicalism—do not show prognostic differences any more [34]; more attention is being paid to quality of life as an indicator of successful surgery. Hereby, subtotal gastric resection is generally understood as the more physiological procedure, supported by postoperative gastrectomy diagnostic findings such as the Dumping Syndrome, postprandial flatulence or pain, and hungry [35]. More recent studies have tried to objectify these ailments and compare quality of life after subtotal resection and gastrectomy according to different scores [36] .

Systematic Lymphadenectomy

Although the role of lymph node dissection had already been realized in the 1940s and 1950s, results were not convincing enough to concede standing to a more radical procedure for surgery treatment of gastric carcinoma . Recognition was emerging gradually owing to Japanese study data. Japanese surgeons practiced for more than two decades systematic extended lymph node dissection (SELD) at gastric carcinoma surgery. Their results underscored the significance of systematic lymphadenectomy for obtaining increased 5-year survival rates [37].

While investigating lymph nodes, the Japanese drew on the cataloging of different lymph nodes described by the Japanese Research Society for Gastric Cancer (1981). Thus, each lymph node is given a number (1–16), gets attributed to an anatomical region, and is then, according to its distance from the stomach, subsumed together with other lymph nodes in a group. There are altogether three groups (compartments).

Compartment I (numbers 1–6) comprises lymph nodes that lie most densely on the stomach wall. Compartment II comprises lymph node numbers 7–11; compartment III, numbers 12–16, comprises lymph nodes further away from the stomach.

1. | Right para-cardial | 9. | Truncus coeliacus |

2. | Left para-cardial | 10. | Spleen hilus |

3. | Smaller curvature | 11. | A. lienalis |

4. | Bigger curvature | 12. | Lig. Hepatoduodenale |

5. | Supra-pyloric | 13. | Retro-pancreatic |

6. | Subpyloric | 14. | Mesenterial radix |

7. | A. gastrica sinistra | 15. | A. colica media |

8. | A. hepatica communis | 16. | Aorta adominalis |

In the wake of increasingly applied SELD, a discussion of how to define this procedure became a crucial issue. So far it had been mostly left to the surgeon to decide how many lymph nodes had to be removed. He oriented himself initially mostly on a medium value of 30 lymph nodes—this medium value was established by Soga and collaborators in the framework of investigating 530 gastrectomies [38].

According to their findings, a lymphadenectomy on gastric carcinoma could be considered sufficient if a minimum of 28 lymph nodes were to be removed. Additionally, they stated that splenectomy alone in addition to lymphadenectomy did not result in remarkable improvement in the sense of radicalness. In the course of a so-called simple gastrectomy an average of 26.2 ± 1.9 lymph nodes were removed. Gastrectomy together with splenectomy could increase the amount only to 29.3 ± 2.3.

The declared aim of extended lymphadenectomy was the enhancement of R0- resections as well as achieving a lymphogene safety distance of resected involved lymph nodes from nonresected, noninvolved lymph nodes of Compartment III. Hence, an improvement of prognosis was to be expected in a single subgroup only, namely in the one that showed exclusively lymph involvement of Compartment I. This expectation was actually corroborated by prospective studies [39].

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree