and associated anatomic compartment (6). Pelvic pressure and discomfort along with visualization of prolapse were strongly associated with worsening stages of POP in all compartments. Impairment of sexual relations, including dyspareunia, and urinary incontinence associated with coitus, as well as duration of abstinence were also strongly associated with worsening POP. Defecatory dysfunction, including incomplete evacuation and digital manipulation, was weakly associated with worsening posterior POP. Similarly, in a multicenter, cross-sectional study, 1,004 women attending routine gynecologic health care underwent POPQ measurements and were surveyed regarding symptoms of disordered defecation (7). Most associations between bowel symptoms and vaginal or pelvic organ descent were weak, although after controlling for important covariates, straining at stool remained associated with anterior vaginal wall and perineal descent. Weber et al also described defecatory dysfunction in association with posterior POP (8). The majority of the sample in this study had stage I or greater posterior POP. While most (92%) reported normal stool frequency, 74% reported straining and 24% strained usually or always. Similarly, 31% required splinting of the posterior vaginal wall or digitation of the rectum during bowel movement, and 16% reported fecal incontinence. Not surprisingly, on a 10-point “bother” scale, the impact of bowel function was 5 or more in 50% and 8 or more in 28%. While these symptoms occur with posterior POP, they also result from other forms of defecatory dysfunction.

TABLE 25.1 Halfway System for Grading Relaxations | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

connective tissue and muscular supports is more subjective.

TABLE 25.2 Differential Diagnosis for Prolapse-Associated Symptoms | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

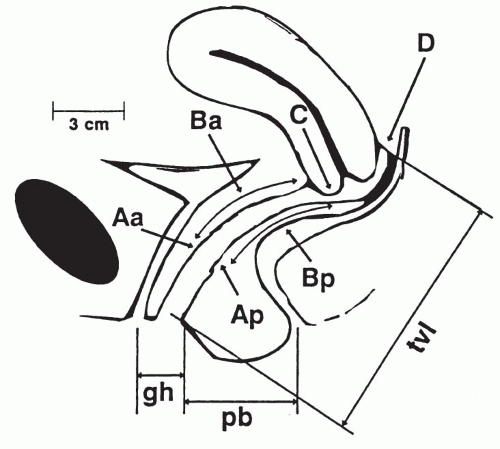

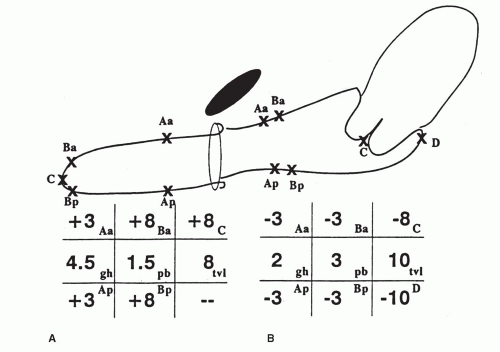

is necessary as staging allows for description and comparison of populations of patients, correlation of symptoms with severity of prolapse, and assessment of treatment outcomes. Unfortunately, the staging system does not predict women who will be symptomatic. For example, a retrospective cross-sectional study assessing prolapse in 905 women using the POPQ examination found no discrete stage that discriminated between symptomatic and nonsymptomatic prolapse (10).

weight, or the prolapse stage or genital hiatus measurement in the lithotomy position (13). POPQ measurements have also been compared by Swift and Herring in the standing and dorsal lithotomy positions (14). A high degree of correlation of measurements in the two positions was found, and it has been postulated that this was related to differences in pelvic tilt produced by standing and dorsal lithotomy positions as compared with a sitting position. As with the McRoberts maneuver, maximum hip flexion is likely to occur in the birthing chair, which results in opening of the pelvic outlet (13,14).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree