Chapter 39 TENSION-FREE VAGINAL TAPE

Correction of female stress urinary incontinence (SUI) with the use of tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) was described in its present form in 1996.1 Its unique features included intentional placement of support at the mid-urethra (previous surgical correction of SUI aimed to suspend the proximal urethra) and the use of a stress test to guide the surgeon in determining the degree of outlet resistance created. The biologically inactive nature of Prolene was recognized, and a Prolene mesh strip was placed to support the mid-urethra. The mesh was held in place by contact with adjacent tissue and was not separately fixed in place.

Ulmsten and colleagues recognized that correction of SUI carried a risk of interference with normal voiding.2 TVT was designed to surgically correct support of the urethra at the level of the mid-urethra, the area where the pubourethral ligaments insert on the urethra. Ulmsten believed that the proximal urethra, the site of initiation of voiding, should be left in its normal, anatomically mobile state. The procedure was also designed to avoid excessive tension on the urethra by including a check mechanism in which mesh placement was adjusted based on a cough stress test. In order to do this, the patient had to remain awake and as close as possible to her normal state, eliciting the SUI.

The procedure was introduced in the United States in November of 1998. It soon became enormously popular with gynecologists and urologists alike, and within 5 years it became the most commonly performed procedure for SUI. With this remarkable change in practice came reports of TVT-associated complications. Shortly after introduction of the TVT procedure into mainstream practice, bowel and large vessel injury were reported.3,4 In some cases, complications resulting from TVT placement had fatal consequences. Such serious complications are exceedingly rare with TVT. Nonetheless, introduction of the procedure into mainstream use brought to light unique challenges inherent in training surgeons to perform it properly and the need to develop an effective credentialing instrument. Furthermore, it was recognized that serious adverse events can occur even when an expert performs the procedure.

TECHNIQUE

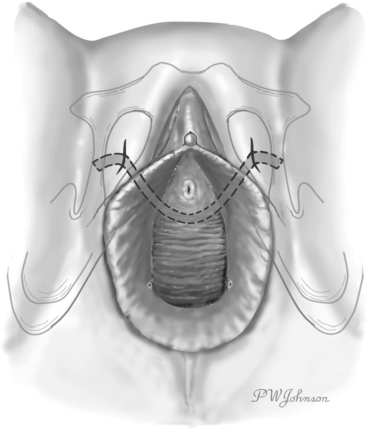

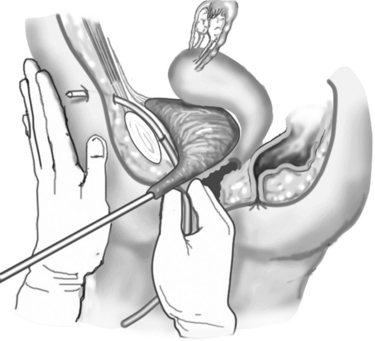

Figures 39-1 and 39-2 illustrate the technique used in the TVT procedure. Use of a vaginal incision (see Fig. 39-1) as opposed to an abdominal incision (see Fig. 39-2) as the starting point for trocar passage is a defining feature for the procedure and verifies accurate placement of support at the mid-urethra. Although the direction of trocar passage has been hypothesized to increase the potential for bladder injury, three randomized comparisons of TVT to conventional sling operations with blind “up to down” mesh introduction showed no difference in the incidence of inadvertent bladder puncture.5–8

The procedure can and should be performed with the patient under local anesthesia and conscious sedation. Data have shown higher rates of voiding dysfunction and lower success rates with procedure deviations in which the cough stress test is not used.9,10 The cough stress test with spinal anesthesia is misleading because of paralysis of the pelvic floor. The TVT procedure is pain free when performed properly and with adequate levels of local anesthetic.11 In the absence of comparative studies with sufficient power to discern small differences in outcome when deviations from the original technique are used, it is our opinion that the TVT procedure should be performed as described by Ulmsten and colleagues,1 using the cough stress test to guide placement.

Figure 39-3 illustrates passage of the introducing trocars. This step is a coordinated motor task without visual input. In other words, placement of the device is “blind.” The tactual and kinesthetic cues involved in passing the trocar through the body are subtle. Bladder perforation is a relatively common complication, and cystoscopy is a required part of the procedure. Whether the procedure is performed by an expert or an amateur, unrecognized bowel injury is a possibility.

PROOF OF CONCEPT

The published clinical experience with TVT is extensive and supports Ulmsten’s promise of a simple, minimally invasive and highly effective solution to incontinence. Four studies have demonstrated minimal or no alteration in proximal urethral mobility after TVT procedure.12–15 In a comparative study of colposuspension and TVT, Atherton and Stanton demonstrated that both procedures resulted in decreased mobility of the proximal urethra, but that statistically greater change was present after colposuspension.16 It is apparent that cure of SUI is possible without affecting proximal urethral mobility.12

Urodynamic studies of voiding after the TVT procedure show conflicting results. Increased urethral resistance is demonstrated in two studies, but not in two others.17–20 In a comparative study, Wang and Chen reported increased urethral resistance and decreased flow rates after colposuspension.19 There was no difference in these measurements after TVT. Both increased and unchanged pressure transmission at the mid-urethra after TVT have been reported.20–22 Conflicting measurements of urodynamic parameters after TVT may reflect small sample size in some of the studies or variable operator experience with the technique. They may also have resulted from the use of spinal anesthesia in two of the studies.19,20 This is a deviation from the original technique, and with motor block of the pelvic floor affecting the cough stress test, it is conceivable that the degree of tension placed on the sling could be affected as well.

The rationale for performing TVT is to avoid overcorrection of anatomy and its systemic consequences. In a randomized comparative trial of TVT and colposuspension, significantly more women underwent corrective surgery for prolapse in the colposuspension group during the 2-year follow-up period.23 Colposuspension, but not TVT, appeared to be causative in the development of the prolapse. There was a statistically significant increased incidence of voiding dysfunction in the colposuspension group at the 2-year follow-up. These findings highlight the importance of minimizing the changes induced in the system to restore continence, to minimize subsequent vulnerability to prolapse or the development of voiding dysfunction.

CONNECTIVE TISSUE RESPONSE

Polypropylene mesh placed near the bladder in rabbits is well accepted by the host without exaggerated inflammation.24 The material is also well accepted in humans, with fibrosis but little inflammatory response to mesh placed in paraurethral tissue.25 Pore size, dimension, and weave of the mesh may also play a role in the host reaction, but they have less impact than the bioactivity of the material itself.

Comparison of bioactivity of Prolene versus Mersilene (polyester) has been made in humans. During the development of the TVT procedure, a high incidence of rejection of urethral slings made of Mersilene, but not slings made of polypropylene, was noted. Given this observation, Falconer and associates correlated clinical outcome with slings of both materials with biochemical measurements of connective tissue taken by biopsy near the site of sling placement.26 Histologic differences were apparent, with greater tissue inflammatory reaction recorded in the Mersilene group. Greater collagen was also present in the Mersilene group, suggesting an increased host response.

The best indicator of the biologic inactivity of Prolene mesh in humans has been the clinical experience that has accrued since introduction of the TVT procedure. Vaginal healing complications have been rare with the TVT technique. In a large analysis of complications associated with the TVT procedure, the incidence of vaginal mesh extrusion was 0.7 %.27 Most of these complications are better termed exposures than erosions, because the technique allows for placement of the polypropylene mesh in the tissue without excessive tension, or hang, on the capillary bed of the surrounding tissue.

Several authors have described conservative management of vaginal mesh exposure (i.e., excision of the exposed fragment and closure).21,28–31

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree