Symptoms of Disorders of the Genitourinary Tract: Introduction

In the workup of any patient, the history is of paramount importance; this is particularly true in urology. It is necessary to discuss here only those urologic symptoms that are apt to be brought to the physician’s attention by the patient. It is important to know not only whether the disease is acute or chronic but also whether it is recurrent, since recurring symptoms may represent acute exacerbations of chronic disease.

Systemic Manifestations

Symptoms of fever and weight loss should be sought. The presence of fever associated with other symptoms of urinary tract infection may be helpful in evaluating the site of the infection. Simple acute cystitis is essentially an afebrile disease. Acute pyelonephritis or prostatitis is apt to cause high temperatures (up to 40°C [104°F]), often accompanied by violent chills. Infants and children who have acute pyelonephritis may have high temperatures without other localizing symptoms or signs. Such a clinical picture, therefore, invariably requires bacteriologic study of the urine.

A history of unexplained attacks of fever occurring even years before may otherwise represent asymptomatic pyelonephritis. Renal carcinoma sometimes causes fever that may reach 39°C (102.2°F) or more. The absence of fever does not by any means rule out renal infection, for it is the rule that chronic pyelonephritis does not cause fever.

Weight loss is to be expected in the advanced stages of cancer, but it may also be noticed when renal insufficiency due to obstruction or infection supervenes. In children who have “failure to thrive” (low weight and less than average height for their age), chronic obstruction, urinary tract infection, or both should be suspected.

Local and Referred Pain

Two types of pain have their origins in the genitourinary organs: local and referred. The latter is especially common.

Local pain is felt in or near the involved organ. Thus, the pain from a diseased kidney (T10–12, L1) is felt in the costovertebral angle and in the flank in the region of and below the 12th rib. Pain from an inflamed testicle is felt in the gonad itself.

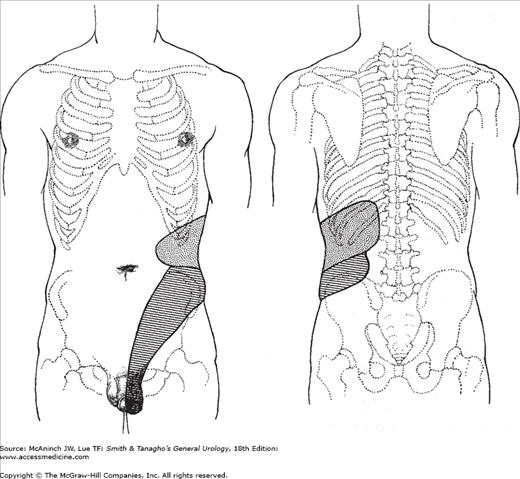

Referred pain originates in a diseased organ but is felt at some distance from that organ. The ureteral colic (Figure 3–1) caused by a stone in the upper ureter may be associated with severe pain in the ipsilateral testicle; this is explained by the common innervation of these two structures (T11–12). A stone in the lower ureter may cause pain referred to the scrotal wall; in this instance, the testis itself is not hyperesthetic. The burning pain with voiding that accompanies acute cystitis is felt in the distal urethra in females and in the glandular urethra in males (S2–3).

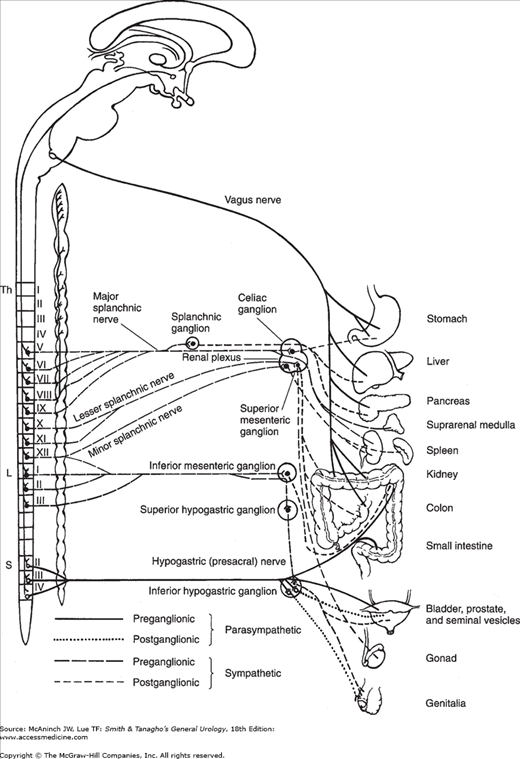

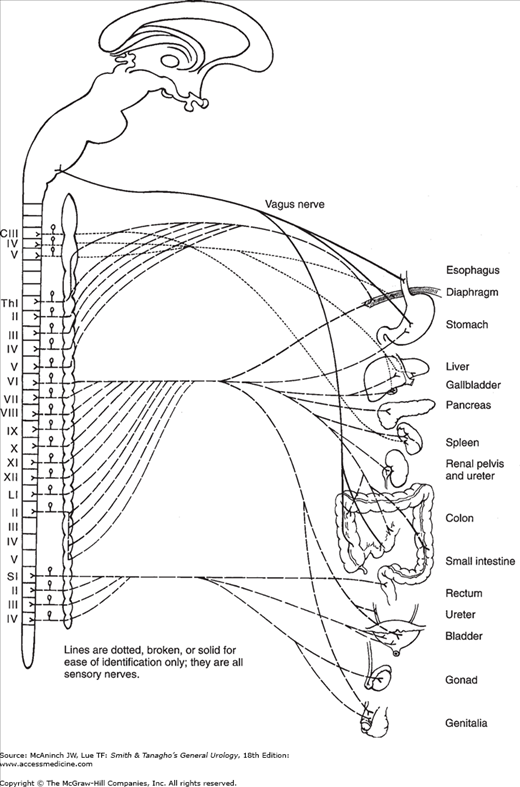

Abnormalities of a urologic organ can also cause pain in any other organ (eg, gastrointestinal, gynecologic) that has a sensory nerve supply common to both (Figures 3–2 and 3–3).

Typical renal pain is felt as a dull and constant ache in the costovertebral angle just lateral to the sacrospinalis muscle and just below the 12th rib. This pain often spreads along the subcostal area toward the umbilicus or lower abdominal quadrant. It may be expected in the renal diseases that cause sudden distention of the renal capsule. Acute pyelonephritis (with its sudden edema) and acute ureteral obstruction (with its sudden renal back pressure) both cause this typical pain. It should be pointed out, however, that many urologic renal diseases are painless because their progression is so slow that sudden capsular distention does not occur. Such diseases include cancer, chronic pyelonephritis, staghorn calculus, tuberculosis, polycystic kidney, and hydronephrosis due to chronic ureteral obstruction.

Ureteral pain is typically stimulated by acute obstruction (passage of a stone or a blood clot). In this instance, there is back pain from renal capsular distention combined with severe colicky pain (due to renal pelvic and ureteral muscle spasm) that radiates from the costovertebral angle down toward the lower anterior abdominal quadrant, along the course of the ureter. In men, it may also be felt in the bladder, scrotum, or testicle. In women, it may radiate into the vulva. The severity and colicky nature of this pain are caused by the hyperperistalsis and spasm of this smooth muscle organ as it attempts to rid itself of a foreign body or to overcome obstruction.

The physician may be able to judge the position of a ureteral stone by the history of pain and the site of referral. If the stone is lodged in the upper ureter, the pain radiates to the testicle, since the nerve supply of this organ is similar to that of the kidney and upper ureter (T11–12). With stones in the midportion of the ureter on the right side, the pain is referred to McBurney’s point and may therefore simulate appendicitis; on the left side, it may resemble diverticulitis or other diseases of the descending or sigmoid colon (T12, L1). As the stone approaches the bladder, inflammation and edema of the ureteral orifice ensue, and symptoms of vesical irritability such as urinary frequency and urgency may occur. It is important to realize, however, that in mild ureteral obstruction, as seen in the congenital stenoses, there is usually no pain, either renal or ureteral.

The overdistended bladder of the patient in acute urinary retention causes agonizing pain in the suprapubic area. Other than this, however, constant suprapubic pain not related to the act of urination is usually not of urologic origin.

The patient in chronic urinary retention due to bladder neck obstruction or neurogenic bladder may experience little or no suprapubic discomfort even though the bladder reaches the level of the umbilicus.

The most common cause of bladder pain is infection; the pain is usually not felt over the bladder but is referred to the distal urethra and is related to the act of urination. Terminal dysuria may be a major complaint in severe cystitis.

Direct pain from the prostate gland is not common. Occasionally, when the prostate is acutely inflamed, the patient may feel a vague discomfort or fullness in the perineal or rectal area (S2–4). Lumbosacral backache is occasionally experienced as referred pain from the prostate, but is not a common symptom of prostatitis. Inflammation of the gland may cause dysuria, frequency, and urgency.

Testicular pain due to trauma, infection, or torsion of the spermatic cord is very severe and is felt locally, although there may be some radiation of the discomfort along the spermatic cord into the lower abdomen. Uninfected hydrocele, spermatocele, and tumor of the testis do not commonly cause pain. A varicocele may cause a dull ache in the testicle that is increased after heavy exercise. At times, the first symptom of an early indirect inguinal hernia may be testicular pain (referred). Pain from a stone in the upper ureter may be referred to the testicle.

Acute infection of the epididymis is the only painful disease of this organ and is quite common. The pain begins in the scrotum, and some degree of neighborhood inflammatory reaction involves the adjacent testis as well, further aggravating the discomfort. In the early stages of epididymitis, pain may first be felt in the groin or lower abdominal quadrant. (If on the right side, it may simulate appendicitis.) This may be a referred type of pain but can be secondary to associated inflammation of the vas deferens.

Gastrointestinal Symptoms of Urologic Diseases

Whether renal or ureteral disease is painful or not, gastrointestinal symptoms are often present. The patient with acute pyelonephritis not only has localized back pain, symptoms of vesical irritability, chills, and fever but also generalized abdominal pain and distention. A patient who is passing a stone down the ureter has typical renal and ureteral colic and, usually, hematuria and may experience severe nausea and vomiting as well as abdominal distention. However, the urinary symptoms so far overshadow the gastrointestinal symptoms that the latter are usually ignored. Inadvertent overdistention of the renal pelvis (eg, with opaque material in order to obtain adequate retrograde urograms) may cause the patient to become nauseated, to vomit, and to complain of cramplike pain in the abdomen. This clinical experiment demonstrates the renointestinal reflex, which may lead to confusing symptoms. In the very common “silent” urologic diseases, some degree of gastrointestinal symptomatology may be present, which could mislead the clinician into seeking the diagnosis in the intraperitoneal zone.

Renointestinal reflexes account for most of the confusion. They arise because of the common autonomic and sensory innervations of the two systems (Figures 3–2 and 3–3). Afferent stimuli from the renal capsule or musculature of the pelvis may, by reflex action, cause pylorospasm (symptoms of peptic ulcer) or other changes in tone of the smooth muscles of the enteric tract and its adnexa.

The right kidney is closely related to the hepatic flexure of the colon, the duodenum, the head of the pancreas, the common bile duct, the liver, and the gallbladder (Figure 1–3). The left kidney lies just behind the splenic flexure of the colon and is closely related to the stomach, pancreas, and spleen. Inflammations or tumors in the retroperitoneum thus may extend into or displace intraperitoneal organs, causing them to produce symptoms.

The anterior surfaces of the kidneys are covered by peritoneum. Renal inflammation, therefore, causes peritoneal irritation, which can lead to muscle rigidity and rebound tenderness.

The symptoms arising from chronic renal disease (eg, noninfected hydronephrosis, staghorn calculus, cancer, chronic pyelonephritis) may be entirely gastrointestinal and may simulate in every way the syndromes of peptic ulcer, gallbladder disease, or appendicitis, or other, less specific gastrointestinal complaints. If a thorough survey of the gastrointestinal tract fails to demonstrate suspected disease processes, the physician should give every consideration to study of the urinary tract.

Symptoms Related to the Act of Urination

Many conditions cause symptoms of “cystitis.” These include infections of the bladder, vesical inflammation due to chemical or x-radiation reactions, interstitial cystitis, prostatitis, psychoneurosis, torsion or rupture of an ovarian cyst, and foreign bodies in the bladder. Often, however, the patient with chronic cystitis notices no symptoms of vesical irritability. Irritating chemicals or soap on the urethral meatus may cause cystitis-like symptoms of dysuria, frequency, and urgency. This has been specifically noted in young girls taking frequent bubble baths.