5 Surgical Procedures to Suspend a Prolapsed Uterus

5-1 Sacrospinous Hysteropexy Anterior Mesh and Posterior Repair

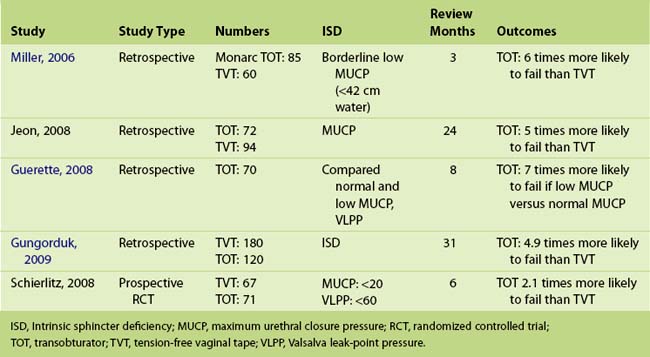

5-2 Sacrospinous Hysteropexy, Anterior Perigee Mesh, Posterior Repair, and Tension-Free Vaginal Tape—the Transobturator Approach

5-3 Sacrospinous Hysteropexy and Posterior Repair

5-4 Large Prolapse Suitable for Anterior and Posterior Colporrhaphy and a Sacrospinous Hysteropexy

5-5 Overactive Bladder Animation

5-6 Abdominal Sacral Colpohysteropexy (Dual-Mesh Technique)

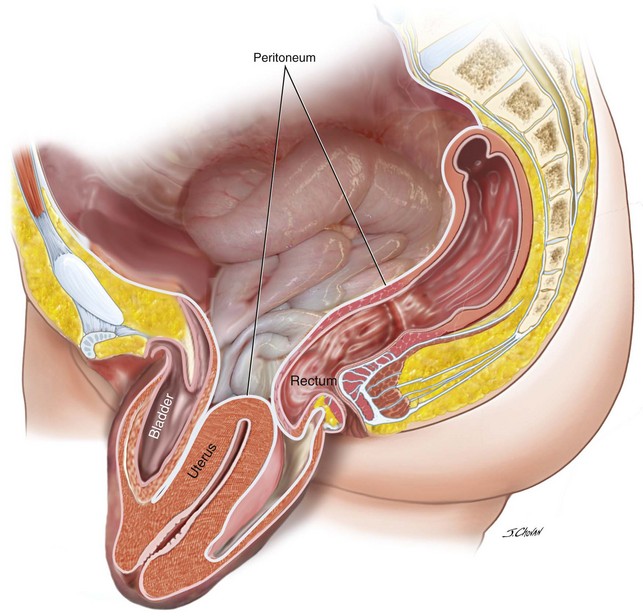

Uterine preservation in prolapse surgery is an attractive option for women for a variety of reasons, including the ability to retain fertility, the desire not to remove a normal organ (the perception is that the cervix is an important structure for pelvic floor stability and sexual satisfaction), and that hysteropexy is a less invasive procedure than hysterectomy with reduced blood loss and surgical time. Because the rate of hysterectomy for menorrhagia is decreasing after the introduction of progesterone-releasing intrauterine devices, all pelvic floor surgeons need to be proficient in uterine preservation techniques for the management of uterine prolapse (Figure 5-1). Table 5-1 lists the advantages and disadvantages of uterine preservation.

Figure 5-1 Lateral view of the pelvis demonstrates uterine procidentia with significant bladder prolapse.

Table 5-1 Perceived and Factual Advantages and Disadvantages of Uterine-Preserving Prolapse Surgery

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Retains fertility. | Retains fertility. |

| Retains a healthy organ. | Menses are ongoing. |

| Perceived role of the uterus and cervix is important in pelvic stability and sexual satisfaction. | Ongoing Gynaecological surveillance of cervix and endometrium is required. |

| Is a less invasive procedure. | Small, ongoing risk for cervical or endometrial cancer exists. |

| Reduces surgical time and blood loss. | If oopherectomy performed at hysterectomy there is no risk of ovarian cancer |

| Offers a quicker recovery. | Sampling cervix or endometrium is difficult. |

| If mesh utilised concomitantly the risk of mesh exposure is reduced at hysteropexy as compared to hysterectomy | Subsequent hysterectomy is difficult, especially if mesh is incorporated in the original prolapse surgery. |

| Retention of the cervix allows continuity between level 2 (native tissue or graft) and level 1 apical compartment repair. | |

| Outcomes are similar with hysterectomy (four case control studies). | Higher failure rate of hysteropexy in one randomized control trial, as compared with hysterectomy. |

Women with increased risk of cervical or endometrial cancer are not candidates for uterine preservation and are excluded if they have any abnormal uterine bleeding, are taking tamoxifen for breast cancer, and have had prior cervical dysplasia abnormalities; they must be prepared to have ongoing routine gynecologic surveillance. Because 0.8% of postmenopausal women undergoing vaginal hysterectomy for prolapse have an incidental finding of endometrial cancer, it has been recommended that all women considering uterine preservation should undergo either transvaginal ultrasound assessment or a histologic assessment of the endometrium before surgery to minimize the risk of preserving a uterus with endometrial cancer (Frick et al, 2010; Renganathan, Edwards, Duckett, 2010). Box 5-1 lists the contraindications to uterine preservation surgery.

Box 5-1

Possible Contraindications for Uterine Preservation

In four case control studies, the sacrospinous hysteropexy (Figure 5-2) was shown to be as effective as hysterectomy for the management of prolapse with a reduction in surgical time, admission time, and a quick return to activities of daily living (Maher, 2001a; Hefni et al, 2003; van Brummen et al, 2003; Dietz et al, 2007). More recently in a randomized controlled trial (RCT), Dietz and colleagues (2007) demonstrated at 12 months a significantly higher recurrence rate after hysteropexy (9 of 34; 27%), as compared with a hysterectomy group (2 of 31; 7%) (p < 0.01). The postoperative total vaginal length was significantly longer in the hysteropexy group, as compared with the hysterectomy group (8.8 and 7.3 cm, respectively; p < 0.001). The failures in this study were all grade 4 uterine prolapse. Clinicians need to be mindful of this latest result and, if verified in further studies, consider it evidence that perhaps uterine preservation in women with large procidentia should be avoided.

One traditional problem associated with sacrospinous colpopexy has been the high rate of postoperative anterior compartment prolapse. With increasing data available that support the efficacy of anterior compartment mesh augmentation, utilising anterior transvaginal mesh in women……is tempting. Hysteropexy and anterior compartment mesh is possibly further appealing when the alternative of vaginal hysterexomy and mesh procedure in a single study increased the risk of vaginal mesh erosion by a factor of 5, compared with those not undergoing hysterectomy (Collinet et al, 2006). The authors of this text recently reported their experience using anterior mesh and hysteropexy in 100 women. At 12 months, the subjective success rate of 84% was achieved with an objective success rate in all vaginal compartments of 75% with a 10% mesh erosion rate. Three women have subsequently undergone vaginal hysterectomy and vault suspension for recurrent uterine prolapse. This surgery requires further evaluation.

Only limited data are available on pregnancy outcome after sacrospinous hysteropexy in the literature. Fourteen women successfully gave birth from 15 pregnancies (1 twin); 6 women delivered by elective cesarean birth, and 9 gave birth vaginally. One in each group underwent subsequent prolapse surgery (Kovac, Cruikshank, 1993; Maher et al, 2001b).

Alternative abdominal approaches include laparoscopic suture hysteropexy and sacral hysteropexy. The plicated uterosacral ligament and cardinal ligaments are resutured to the cervix during laparoscopic suture hysteropexy (Maher, 2001a). Although the procedure is simple and safe, the objective success rate was only 79% at 12 months with the main problem being cervical elongation. The authors of this text rarely perform this technique.

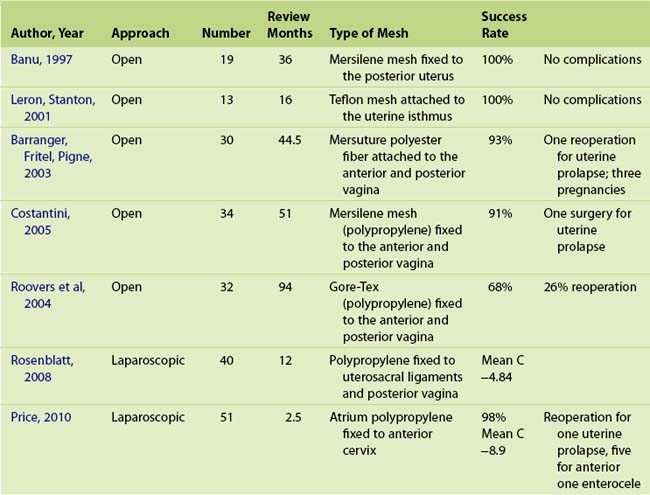

The sacral hysteropexy is often suggested as the abdominal approach to uterine preservation (Table 5-2) and has been described since 1997. Because of excellent outcomes with sacral colpopexy anecdotally, this procedure is gaining in popularity. Less than 180 cases with a relatively long period of review (12 to 94 months) are reported in the literature (Table 5-3). Three pregnancies have been reported, but no data on deliveries or on the impact of pregnancy or childbirth on prolapse surgery are available. Reoperation for prolapse has been reported in 10 patients. Standardization in the choice of graft and the surgical technique of attaching the graft to the uterus or vagina is distinctly lacking. Three surgeons used a single sheet of mesh attached to the posterior cervix or vagina and three used two sheets of mesh attached to the anterior and posterior vagina connected via the broad ligament. Two case series reported satisfactory outcomes after the laparoscopic approach with early follow-up and with different surgical techniques. Rosenblatt et al, 2008 attached the mesh to the uterosacral ligaments and posterior cervix, whereas Price et al, 2010 attached the mesh to the anterior cervix. The paucity of data on this technique may reflect a reluctance of surgeons to perform this relatively technical and challenging surgery when an effective vaginal approach is available; secondarily, any future hysterectomy and or prolapse surgery would be difficult.

Several authors have reported objective success rates of over 90% with sacral hysteropexy (Leron, Stanton, 2001; Barranger, Fritel, Pigne, 2003), in which mesh secures the cervix to the sacrum. In one RCT, Roover and associates (2004) compared sacral hysteropexy with vaginal hysterectomy and repair. They reported a significantly higher resurgical rate for prolapse in the hysteropexy group. Cosson has advocated uterine preservation as part of the total vaginal mesh repair because hysterectomy was an independent risk factor for mesh complications (Collinet et al, 2006); however, little data are available for total vaginal mesh with uterine preservation.

Case 1: Sacrospinous Hysteropexy Anterior Mesh and Posterior Repair

View: Video 5-1

View: Video 5-1

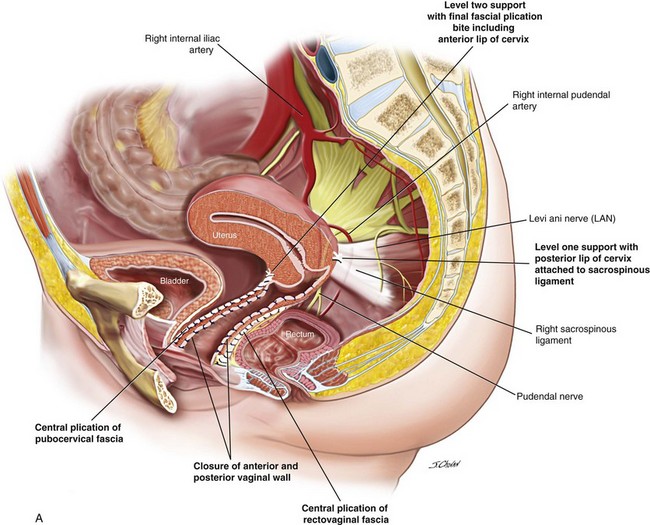

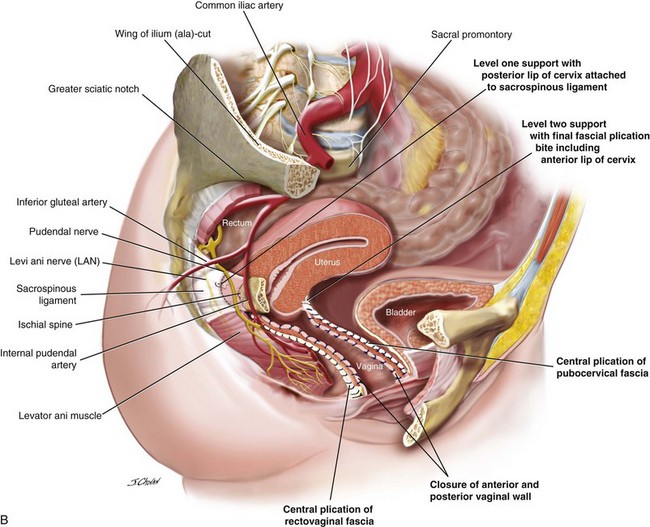

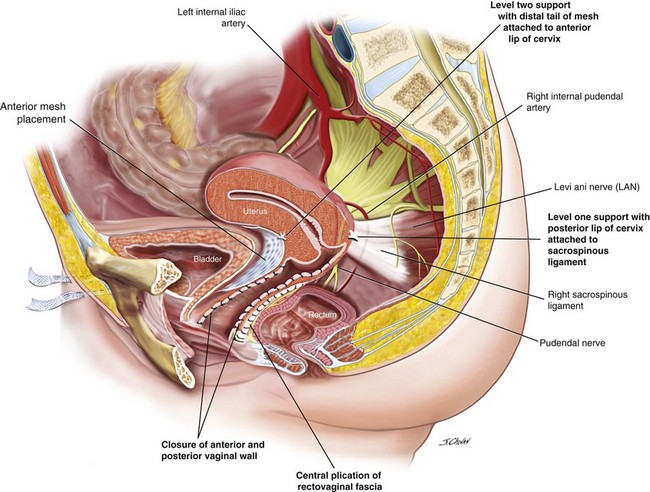

After the various surgical options were discussed, including hysterectomy, the patient elected to undergo sacrospinous hysteropexy, anterior Prolift mesh, and posterior vaginal repair (Figure 5-3).

Surgical Steps

1. Hydrodissection with 50 ml Marcaine solution 0.25% and adrenalin floods the anterior and posterior vaginal walls.

2. A midline incision is made in the anterior vaginal mucosa, and the bladder is reflected medially from the vaginal mucosa out to the inferior pubic rami to create a paravesical space. The bladder is also mobilized from the anterior cervix.

3. The anterior Prolift mesh is introduced with care to ensure that the bladder is protected from inadvertent damage during the introduction of trocars to the paravesical spaces (see Chapter 8, Surgical Management of Anterior Vaginal Wall Prolapse). The distal tail of the mesh is secured to the anterior cervix, and the proximal mesh is fixed to the paraurethral mucosa with 2.0 Vicryl suture. Initial tensioning of the mesh is performed to ensure that the mesh sits loosely below the bladder. The anterior vaginal mucosa is closed with a continuous 2.0 Vicryl suture.

4. The posterior vaginal compartment is opened, bilaterally creating the pararectal space. The right pararectal space is bordered by the right puborectalis muscle laterally and inferiorly, the rectum medially, and the coccygeus muscle and the sacrospinous ligament (SSL) running from the ischial spine to the medial edge of the sacrum at the apex.

5. Sutures traverse the SSL 2 cm medial to the ischial spine using the Miya Hook. Usually, two sutures are loaded for each pass, and delayed absorbable 2.0 polydioxanone sutures (PDSs) are used to secure the vagina to the ligament, and a Gore-Tex permanent suture secures the distal posterior margin of the cervix to the SSL. Any permanent suture may be used for the hysteropexy suture; however, because the vaginal suture traverses the vaginal mucosa, a permanent suture may result in granulation tissue or sinus formation (or both).

6. The rectovaginal fascia is centrally plicated with 2.0 PDSs.

7. A Gore-Tex sacrospinous suture is distally inserted through the cervix with a No. 3 Mayo needle, and a second PDS is inserted through the left and right sides of the incised vaginal mucosa.

8. The posterior vaginal mucosa is closed with 2.0 Vicryl to approximately the lower one third, and the sacrospinous hysteropexy suture is tied. The posterior vaginal mucosa is closed to the introitus, and the vaginal sacrospinous suture is tied.

9. Finally, the mesh is tensioned so it sits just below the bladder with no excessive tension on the mesh or arms. The sheath over the mesh arms are removed and the mesh is trimmed from the exit points in the groin.

10. The perineum is reconstituted.

11. A cystoscopy is performed to ensure that the bladder mucosa is intact and that the ureters are patent. A rectal examination is completed to ensure that the rectal mucosa is intact.

12. Antibiotics are initiated, thromboembolic stockings are worn for 7 days, and self-administered enoxaparin sodium (Clexane) (20 mg) is injected daily for 5 days for every patient. Patients at high risk of thromboembolic events must complete an extended course of self-administered Clexane (40 mg).

13. The vaginal pack is removed at 6:00 AM after surgery, and the indwelling catheter is removed at 12:00 PM; a trial of void is started.

See Video 5-1 for a demonstration of sacrospinous hysteropexy, anterior mesh, and posterior repair. ![]()

Case Discussion

Although the symptoms of voiding dysfunction preoperatively are unreliable, the authors routinely perform urodynamic evaluation before surgery in all women with large prolapse and in women with any symptoms of voiding difficulties to document flow rate, detrusor-voiding pressure, and residual urine. Before prolapse surgery, most women mistakenly believe that prolapse surgery will correct associated bladder symptoms. The surgeon is responsible for discussing these issues preoperatively and for informing the patient that she has a small risk of preoperative voiding symptoms persisting after surgery. Women with normal voiding preoperatively are informed of a small risk for the development of new voiding difficulties that may require clean, intermittent, postoperative self-catheterization, as stated on the procedure-specific consent form. As previously documented by the authors of this text, of the 14 women who underwent sacral colpopexy or vaginal sacrospinous colpopexy with significant stage 2 prolapse and preoperative voiding difficulties, 11 (78%) had postoperative resolution of voiding symptoms (Maher et al, 2004).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree