3 Preoperative Evaluation and Staging of Patients with Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Taking a Good History

A variety of standardized questionaires (Burrows, 2004) can be used to assess fully the patient’s perception of her pelvic floor symptomatology. Preferably, the patient completes these questionnaires before beginning the interview process. Although not always possible, these questionnaires allow the health care provider to appreciate the daily impact of these various problems. A voiding diary, which a patient maintains for 1 to 3 days, may also be helpful; as many of these patients have significant lower urinary tract dysfunction.

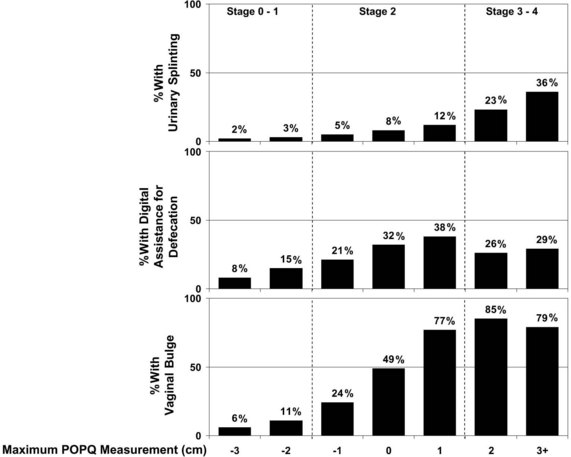

Vaginal prolapse in any compartment—anterior, apical, or posterior—can cause vaginal fullness, pain, and/or a protruding mass. In a recent study by Tan and colleagues (2005), the feeling of “a bulge or that something is falling outside the vagina” had a positive predictive value of 81% for POP, and the lack of this symptom had a negative predictive value of 76% for predicting prolapse at or past the hymen. Not surprisingly, an increased degree of prolapse, especially beyond the hymen, is associated with increased pelvic discomfort and the visualization of a protrusion. The association of Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POPQ) measurements during the examination with three commonly related symptoms—urinary splinting, digital assistance with defecation, and vaginal bulge—is shown in Figure 3-1.

Although the relationship between sexual function and POP is not clearly defined, questions regarding sexual dysfunction must be included in the evaluation of any patient with POP. Patients may report symptoms of dyspareunia and decreased libido and orgasms, as well as increased embarrassment because of an altered anatomy that affects body image. Some studies have reported that prolapse adversely affects sexual function, with subsequent improvement in sexual function after the repair of prolapse. (Barber et al, 2002; Rogers et al, 2001; Weber, Walters, Piedmonte, 2000) However, Burrows and associates (2004) showed little correlation between the extent of the prolapse and sexual dysfunction. Evaluating sexual function may be especially difficult in this patient population, secondary to the presence of factors other than prolapse, such as partner limitations and functional deficits.

Examination

After the resting vaginal examination, the patient is instructed to perform a Valsalva maneuver or to cough vigorously. During this maneuver, the order and extent of the descent of the pelvic organs is noted, as is the relationship of the pelvic organs to each other at the peak of increased intraabdominal pressure. The presence and severity of anterior vaginal relaxation, including cystocele and proximal urethral detachment and mobility or anterior vaginal scarring, are estimated. Associated pelvic support abnormalities, such as rectocele, enterocele, and uterovaginal prolapse, are also noted. The amount or severity of prolapse in each vaginal segment should be measured and recorded using a standardized reproducible system for staging (see pages 34-37). A rectovaginal examination is required to evaluate fully the prolapse of the posterior vaginal wall and perineal body. Digital assessment of the bowel contents in the rectovaginal septum during the straining examination can help diagnose an enterocele. Inspection should also be made of the anal sphincter; as fecal incontinence can be associated with posterior vaginal support defects. Women with a torn external sphincter may have scarring or what has been termed a dovetail sign. (See Video 3-1, “Live Demonstrations of a Variety of Women with Advanced Prolapse” ![]() )

)

Anterior vaginal wall descent usually represents bladder descent with or without concomitant urethral hypermobility. The anterior vaginal wall prolapse is believed to be the result of a midline defect, a paravaginal defect, or, less commonly, a transverse defect. These defects may co-exist or occur in isolation. Although clinicians have attempted to describe techniques to differentiate these various defects during the physical examination, researchers have shown that the preoperative predictability is not particularly reliable or accurate. In a study by Barber and associates (1999) of 117 women with prolapse, the sensitivity of the clinical examination to detect paravaginal defects (92%) was good, yet the specificity (52%) was poor. Despite a high prevalence of paravaginal defects, the positive predictive value was only 61%. Less than two thirds of women believed to have a paravaginal defect on physical examination were confirmed to possess the same at surgery. Another study by Whiteside and colleagues (2004) demonstrated poor predictability and reproducibility of the clinical examination to differentiate various anterior vaginal wall defects. Thus the clinical value of attempting to determine preoperatively the defect that is responsible for the anterior wall prolapse is low.

Clinical examinations do not always accurately differentiate rectoceles from enteroceles in posterior prolapse. Thus some investigators have advocated performing imaging studies to delineate further the exact nature of the posterior wall prolapse. Traditionally, most clinicians believe that they are able to detect the presence or absence of these defects without anatomically localizing them. However, little is known regarding the accuracy or use of clinical examinations in the evaluation of the anatomic locations of prolapsed small or large bowel or of specific defects in the rectovaginal space. Burrows and associates (2003) found that clinical examinations often did not accurately predict the specific location of defects in the rectovaginal septum that was subsequently found intraoperatively. Clinical findings corresponded with intraoperative observations in 59% of patients and differed in 41%; sensitivities and positive predictive values of clinical examinations were less than 40% for all posterior defects. However, the clinical consequence of not preoperatively detecting defects remains unclear.