9 Surgical Correction of Posterior Pelvic Floor Defects

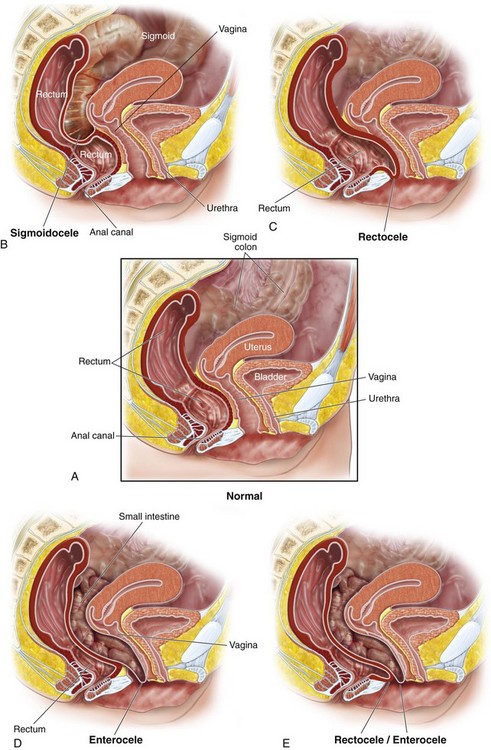

Posterior pelvic floor defects include a variety of pelvic floor support disorders and anatomic defects of the anal sphincter. These various abnormalities may be asymptomatic, create traditional symptoms of prolapse, or result in a variety of functional arrangements. Posterior vaginal wall prolapse co-exists with anterior or apical prolapse in up to 50% of patients. Various types of posterior wall prolapse include a posterior enterocele, rectocele, sigmoidocele, and perineal descent (Figure 9-1). Although these various defects can occur in isolation, they commonly occur in combination. Defects in the external anal sphincter, which anatomically make up a significant portion of the perineum, can contribute to a gapping perineum and may also contribute to incontinence of either gas, liquid, or solid stool.

Figure 9-1 Different types of posterior pelvic floor prolapse.

(From Hull TL: Posterior pelvic floor abnormalities. In Karram M, editor: Female pelvic surgery video atlas series. Philadelphia, 2011, Elsevier.)

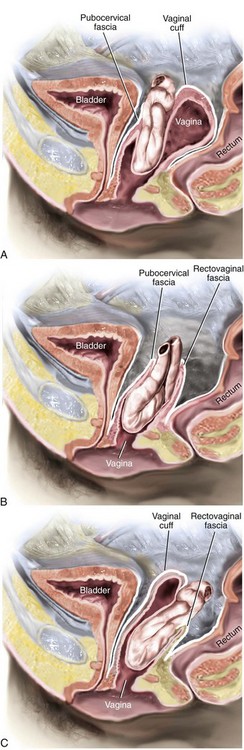

An enterocele is a hernia in which the peritoneum and abdominal contents displace the vagina and may even be in contact with vaginal mucosa. The normal intervening endopelvic fascia is deficient or absent, and small bowel fills the hernia sac. Generally, enteroceles have been divided into four types: congenital, traction, pulsion, and iatrogenic. Factors that may predispose a woman to the development of congenital enteroceles include neurologic disorders such as spina bifida and connective tissue disorders. Traction enteroceles occur secondary to uterovaginal prolapse, and pulsion enteroceles are the result of prolonged increases in intraabdominal pressure. Iatrogenic enteroceles occur after surgical procedures that elevate the normally horizontal vaginal axis in a vertical direction, such as a colposuspension for stress incontinence or after hysterectomy if the vaginal cuff and cul-de-sac are not appropriately managed. Clinically, enteroceles are best classified based on their anatomic location. Apical enteroceles herniate through the apex of the vagina, posterior enteroceles herniate posteriorly to the vaginal apex, and anterior enteroceles herniate anterior to the vaginal apex (Figure 9-2).

Figure 9-2 Cross-section of pelvic floor shows various anatomic locations of enteroceles.

(Modified from Walters MD, Karram MM, editors: Urogynecology and reconstructive pelvic surgery, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2007, Elsevier.)

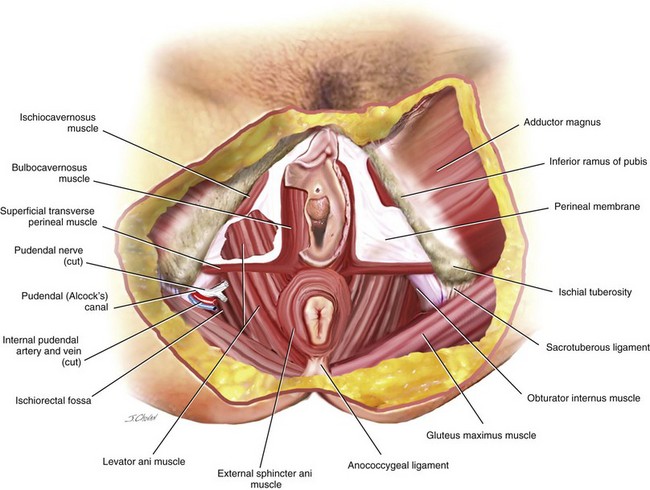

DeLancey (1999) divided the connective tissue support of the vagina into three levels. All three levels of support should be evaluated and addressed during the surgical management of the posterior vaginal wall. Level I support is the uppermost or apical portion of the posterior vaginal wall and is suspended and supported primarily by the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments. Level II support includes the support of the middle half of the vagina, and this support is provided by the endopelvic fascia attaching the lateral posterior vaginal wall to the aponeurosis of the levator ani muscle on the pelvic side wall. The perineal body includes interlacing muscle fibers of the bulbocavernosus, transverse perineal, and external anal sphincter muscles. Anteriorly, the perineum is attached to the vaginal epithelium and muscularis of the posterior vaginal wall. Laterally, it is attached to the ischiopubic ramus through the transverse perineal muscles and the perineal membrane. The perineal body is described as extending cranially on the posterior vaginal wall to approximately 2 to 3 centimeters proximal to the hymenal ring. This dense fused level of support is what DeLancey has described as level III support. Posterior to the perineal body includes the anterior portion of the external anal sphincter and its attachment to the longitudinal fibrous sheet of the internal anal sphincter (Figure 9-3). (See Video 9-1, “Anatomy of the Posterior Vaginal Wall.” ![]() )

)

Patients with posterior vaginal prolapse may be totally asymptomatic or may have a variety of anatomic and functional complaints. In general, before surgical correction, testing should be undertaken that might help the surgeon truly determine whether anatomic correction will result in symptomatic relief of the patient’s complaints. This chapter discusses a variety of techniques used to correct posterior vaginal wall prolapse and perineal defects. (The history, physical examination, and staging of posterior vaginal wall prolapse are discussed in Chapter 3.)

Preoperative Considerations before Surgical Repair

Ellerkmann and colleagues (2001) reported that 25% to 67% of patients with pelvic organ prolapse admit to symptoms of defecatory dysfunction. These symptoms include straining to have a bowel movement, having to splint to facilitate expulsion of stool, dyschezia, chronic constipation, and occasional fecal incontinence. Patients may also complain of symptoms related to sexual function. Patients who have an anatomic defect with primarily functional complaints must be thoroughly evaluated and consented before undergoing a surgical procedure, because the correlation between correcting the defect and restoring the functional problems is at times unpredictable. A physical examination should entail a close inspection and assessment of the degree of prolapse, the state of the perineum, the total vaginal length, and the extent and size of the genital or levator hiatus. A rectal examination is performed to further assess the presence and position of a rectocele, as well as help differentiate a rectocele from an enterocele. Inspection and examination of the anal area is also indicated with one finger in the rectum and another in the vagina. A sliding posterior enterocele may be palpated as prolapsed loops of small bowel will become apparent between the intervening tissues of the rectovaginal septum.

Surgical Management of Posterior Compartment Defects

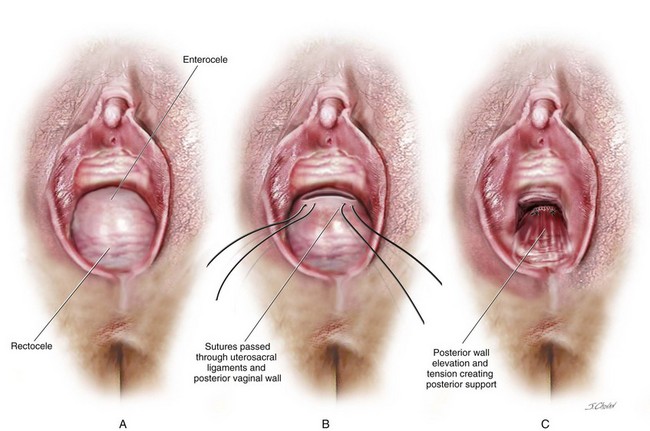

The published literature continues to classify rectocele repairs into what has been termed as the traditional technique, which implies that the repair has been supplemented with a levator ani muscle plication in the midline, or a site-specific technique, which implies that discrete defects in the rectovaginal fascia are identified and repaired and that no levator plication is performed. To date, no studies have addressed how often a posterior enterocele and or sigmoidocele co-exist with a rectocele or how the presence of these defects impacts ultimate surgical outcomes. Based on the current understanding of the anatomy of the posterior vaginal wall and perineum, defect-specific repairs clearly involve plication of the fibromuscular layer of the posterior vaginal wall. Based on the initial level of dissection, this tissue may be found on the anterior wall of the rectum or may have to be mobilized off the vaginal epithelium to allow an appropriate tension-free plication. In patients with advanced prolapse and a widened genital hiatus, the only way to address the gaping vagina is to perform a distal levatorplasty. In the author’s opinion, future surgical studies assessing the outcomes of prolapse repair involving the posterior vaginal wall should take into consideration these points and realize that these procedures are not mutually exclusive; a combination of the techniques, especially in cases of advanced prolapse, is commonly required. Other types of repair that have been reported include transanal repairs, transperineal mesh (biologic or synthetic) augmented repairs, and abdominal sacral colpopexy in which the mesh attachment is extended down to the distal portion of the posterior vaginal wall and/or perineum. The author has also observed that aggressive reattachment of the uppermost portion of the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall (level I support) to the uterosacral ligament provides significant support to the posterior vaginal wall in patients with high rectoceles or rectoceles in conjunction with a posterior enterocele (Figure 9-4).

Technique for Rectocele Repair and Perineoplasty

1. The patient is placed in the lithotomy position in high leg stirrups, and the vagina is sterilely prepared and draped. A catheter is placed to empty the bladder. A pelvic examination under anesthesia, including a careful rectovaginal examination, is performed. The thickness and laxity of the posterior vaginal wall and rectovaginal septum is palpated and closely observed, including how much displacement of the rectal wall protrudes toward the vagina with a palpating finger. The wideness of the levator hiatus and the quality of the levator muscles are bilaterally estimated; the perineal body, not only its length from the posterior fourchette to anus but its thickness, is also palpated. Sometimes a distal perineal rectocele can be quite symptomatic and is only palpable when the rectal finger is hooked backward toward the surgeon during a rectovaginal examination. Because one of the complications of rectocele repair is overzealous fibromuscular or levator plication resulting in vaginal constriction and dyspareunia, the desired caliber of the vagina along its length and especially near the introitus at the hymenal ring is carefully estimated.

2. Two Allis clamps are placed at the posterior fourchette at approximately 5 and 7 o’clock and are gently pulled downward to examine the entire posterior vaginal wall and to again estimate the amount of gaping of the introitus. A dilute hemostatic solution, such as 0.5% Lidocaine with 1 : 200,000 epinephrine, is injected into the perineum and rectovaginal space. A Lone Star retractor is sometimes useful to help visualize the entire vagina and aid in retraction during a rectocele repair.

3. Some surgeons make a V or diamond incision in the perineum to resect the redundant tissue, and others simply make a midline incision. The authors prefer to excise a diamond-shaped piece of perineal and vaginal skin, based on the desired caliber of the vagina and introitus (Figure 9-5). Once this tissue is excised, Allis clamps are used to grasp the edges of the vaginal epithelium. The author perfers to perform this dissection and the entire repair with a finger in the rectum.

4. The Allis clamps help retract the incised vaginal wall by lifting it. The index finger of the nondominant hand of the surgeon is in the rectum to apply countertraction against the elevated vaginal wall. The rectovaginal space is sharply incised using scissors until the entire vagina is dissected off the rectum to the levator ani muscles, which is done bilaterally and proximally; the rectum is separated off the vagina toward the vaginal apex. Once the dissection extends beyond the extraperitoneal portion of the rectum, the rectovaginal space is entered. This is an avascular preperitoneal space that allows access to the peritoneum over the cul-de-sac. At times an enterocele can be in the rectovaginal space over the rectocele; consequently, the surgeon should inspect for this and, if an enterocele is identified, correct it (Figure 9-6) The reader is referred to the section, “Technique for Enterocele Repair” on page 150 for a more detailed description. Likewise, if apical prolapse exists, then a sacrospinous ligament or uterosacral colpopexy can be performed before the rectocele repair is completed.

5. A series of sutures are progressively placed bilaterally through the fibromuscular tissue to reduce the rectocele. The vagina should be examined after every two or three sutures to ensure that the posterior vaginal wall is smooth and not becoming too tight during the repair. In addition, irregularities in the posterior vaginal wall from sutures placed at slightly different levels may result in dyspareunia; the offending sutures should be removed and replaced to ensure that the posterior vaginal wall repair is smooth. The repair is begun proximally and extends in a distal direction. The author prefers to perform a two-layered plication when possible (see Figure 9-6).

6. Mixing a partial fibromuscular plication with areas of site-specific defect repair is acceptable, especially in the distal posterior vaginal wall. The surgeon may note a defect in the midline, right, left, or at the perineal body and may be able to identify edges of the fibromuscular tissue or rectovaginal septum. In this case, sutures are placed to repair the defect and even to connect the perineal body to the rectovaginal septum. Performing the repair with a finger in the rectum facilitates the placement of the stitches (Figure 9-7).

7. If necessary, a perineorrhaphy is then performed to help thicken the perineum, both in the craniocaudal direction and in the anteroposterior direction. A rectovaginal examination verifies whether the rectocele has been completely corrected and whether sutures or lacerations are no longer present in the rectal mucosa. The surgeon must be careful not to constrict the hymenal ring too much, which is a frequent cause of entry dyspareunia.

8. The rectovaginal space is carefully visualized for all bleeding vessels that are appropriately cauterized. The rectovaginal space is irrigated, and closure of the posterior vagina is started with a fine running or interrupted delayed absorbable suture. Sometimes, some redundant vaginal wall should be trimmed; however, care should be taken not to over trim and constrict the vagina. The sutures to the hymen are locked, and then the perineorrhaphy incision is closed with simple running or interrupted sutures.

9. No studies have indicated the best type of sutures for rectocele repair. A reasonable choice is a delayed absorbable suture, such as 2.0 Vicryl for the fibromuscular plication of the rectum and the reconstruction of the perineal body; 3.0 Vicryl can be used for closing the posterior vaginal wall and perineal skin.

10. Vaginal packing is reasonable to help decrease the incidence of rectovaginal septum hematoma, but it is not mandatory.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree