8 Surgical Management of Anterior Vaginal Wall Prolapse

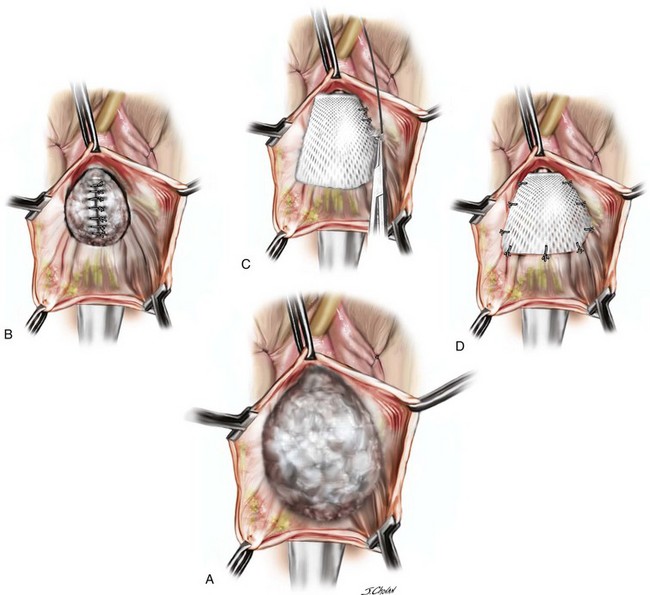

8-1 Anterior Colporrhaphy with Biologic Mesh Augmentation

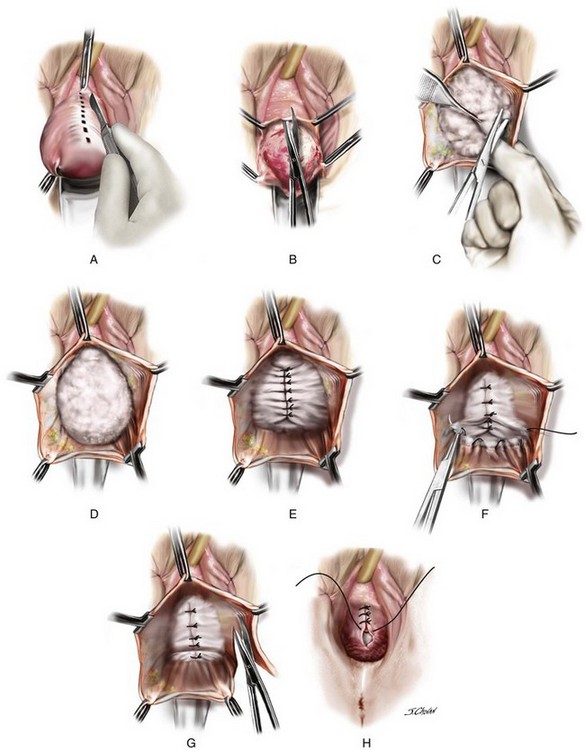

8-2 Anterior Repair with Midline Fascial Plication

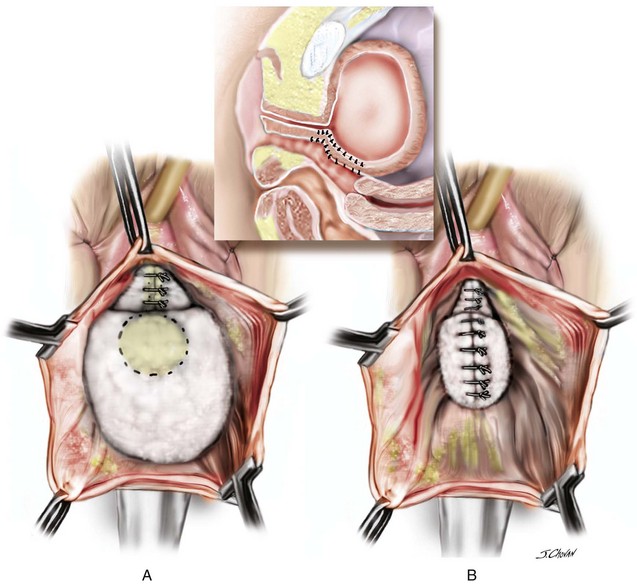

8-3 Anterior Colporrhaphy with Kelly Plication

8-4 Large Prolapse Suitable for Anterior Colporrhaphy

8-5 Laparoscopic Paravaginal Repair

8-6 Demonstration of Occult Incontinence

8-7 Anterior Prolift Sacrospinous Hysteropexy Posterior Repair

8-8 Sacrospinous Hysteropexy, Anterior Perigee Mesh, Posterior Repair Tension-Free Vaginal Tape—the Transobturator Approach

8-9 Mesh Augmented Anterior Repair with Vaginal Hysterectomy Using the Anterior Elevate System

8-10 Mesh Augmented Anterior Repair Using Anterior Elevate for Recurrent Cystocele

Introduction

In 1909, White stated that the only unresolved problem in plastic gynecology was the permanent cure of cystocele (White, 1909). Today, the surgical management of anterior compartment prolapse remains problematic and controversial. Anterior compartment prolapse is the most common site of prolapse and the site of prolapse with the highest anatomic failure rate with a plethora of surgical options available to the clinician. The goal of this chapter is to provide an overview of the current literature and to discuss and demonstrate numerous approaches to the surgical management of anterior compartment prolapse.

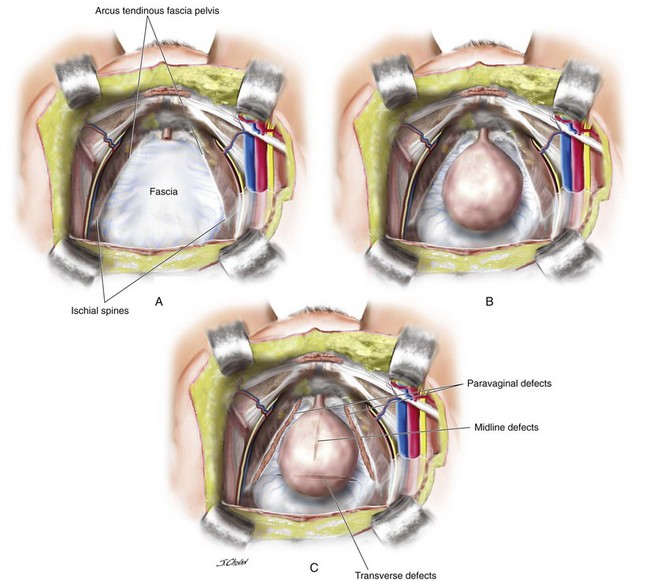

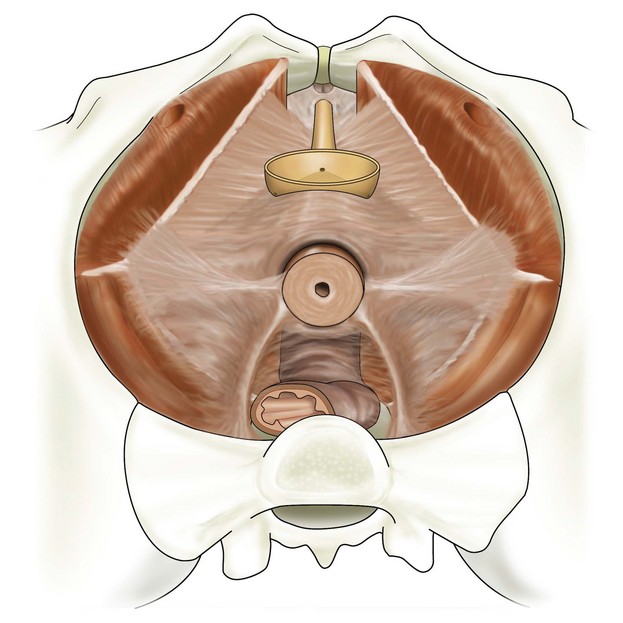

Anterior vaginal wall prolapse, commonly termed cystocele, is defined as the pathologic descent of the anterior vaginal wall overlying the bladder base. Cystocele may frequently co-exist with a variety of micturition disorders. The most contemporary understanding of the anatomy and support of this segment of the pelvic floor stems from concepts proposed by Richardson 1976, who described transverse, midline, and paravaginal defects. Transverse defects were said to occur when the pubocervical fascia separated from its insertion around the cervix; midline defects represented an anteroposterior separation of the fascia between the bladder and the vagina; and paravaginal defects represented a detachment of the lateral connective tissue attachments at the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis (ATFP). A conceptual representation of these various defects viewed from the retropubic space is shown in Figure 8-1.

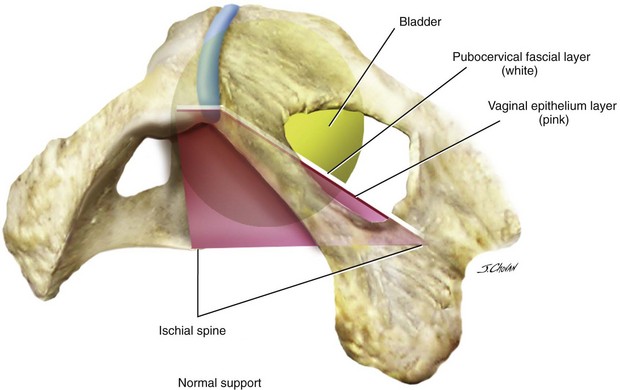

All types of micturition disorders can be observed with anterior vaginal wall prolapse, and, to date, no clear scientific explanation exists to help clinicians understand the correlation between the anatomic descent of the anterior vaginal wall and the functional derangements of the urinary tract. When evaluating and planning the surgical management of patients with anterior vaginal wall descent, determining how the surgical intervention will affect any potential functional derangements that the patient may be experiencing is important. This aspect of the preoperative discussion with the patient and the consent process is extremely important. Although many surgeons have gone to great lengths to predict preoperatively what types of defect exist in patients with symptomatic anterior wall descent, the literature suggests that doing so is difficult to do, and, in reality, the determination of the various defects in the authors’ opinion is an intraoperative finding with questionable clinical utility. Although numerous types of repairs are discussed and demonstrated in great detail in this chapter, the ultimate goal of any anterior vaginal wall support procedure is to recreate a trapezoid of support that mimics the pubocervical fascia and stems from below the proximal urethra to the cervix or apex and laterally to the ATFP or fascia of the obturator internus muscle (Figure 8-2).

Background

In 1913, Kelly described the plication of the urethral sphincter muscle and the anterior colporrhaphy was born. The success rates of anterior colporrhaphy in the management of cystocele range from 80% to 100% in retrospective series. (Macer, 1978; Stanton et al, 1982; Walter et al, 1982; Porges, Smilen, 1994) More recently, Weber and colleagues (2001) and Sand and associates (2001) in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) reported anterior colporrhaphy to be successful in the management of cystocele in only 42% and 57% of cases, respectively.

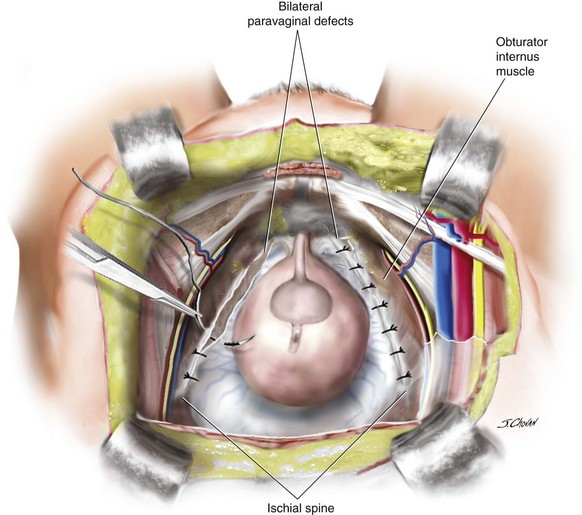

White (1912) demonstrated the importance of paravaginal defects in anterior compartment prolapse. Richardson, Lyon, Williams (1976) described a series of defects in the pubocervical fascia, explaining why no single repair should be indiscriminately applied to all anterior compartment defects. He also advocated the abdominal paravaginal repair (Figure 8-3), which has a reported success rate of 75% to 97% in numerous case series. (Richardson, Lyon, Williams, 1976; Richardson, Edmonds, Williams, 1981; Shull, Baden, 1989; Scotti et al, 1998; Bruce, El Galley, Galloway, 1999) The surgical technique of the laparoscopic paravaginal repair is well described, but little information is available on the efficacy of this approach.

Shull and colleagues (1994) also reported on the safety and efficacy of the transvaginal paravaginal repair (Figure 8-4) in 1994. Although the success rates of the transvaginal paravaginal repair for cystocele in case series vary from 67% to 100% (White, 1912; Shull, Benn, Kuehl, 1994; Grody et al, 1995; Elkins et al, 2000; Mallipeddi et al, 2001; Young, Daman, Bony, 2001), significant complications have been reported. Mallipeddi reported on complications in a series of 45 patients including one bilateral ureteric obstruction, one retropubic hematoma requiring surgery, two vaginal abscesses, and two transfusions. In a series of 100 women, Young, Daman, Bony (2001) reported 21 major complications and a 16% transfusion rate.

In line with our surgical colleagues who moved to utilise mesh in hernia repairs, in the last decade there has been to move toward graft prosthesis in prolapse surgery. This movement took much of its impetus from two early papers. Olsen 1997 reported a reoperation rate of 29% after prolapse and/or continence surgery; Weber reported a 70% failure rate of native tissue in anterior compartment repair. A recent re-evaluation of Olsen’s same demographic criteria 10 years later revealed a more acceptable re-operation rate of 17% (Denman et al, 2008). In addition, a recent re-analysis of Weber’s data using a less strict definition of objective success reveals outcomes to be considerably better than originally reported with only 10% of patients developing anatomic recurrence beyond the hymen, 5% developing symptomatic recurrence, and reoperation rates less than 1% at 23-months’ follow-up. (Chmielewski et al, 2011) These re-evaluations 10 years after the primary publications challenge the reasoning that validates the introduction of transvaginal polypropylene mesh augmentation.

Historically, clinicians have sought more durable repairs. Julian and colleagues (1996) demonstrated in a prospective case control study that women who underwent at least two previous vaginal repairs, the overlaying of a Marlex (Bard) mesh to the anterior colporrhaphy reduced the recurrence rate of cystocele from 33% to 0%. The Marlex mesh was associated with a mesh erosion rate of 25%. In a retrospective review of 142 women with Marlex mesh augmentation of the anterior colporrhaphy, Flood, Drutz, Waja (1998) demonstrated a 100% success rate for cystoceles at a 3.2-year follow-up and a mesh erosion rate of only 2%. Although the Marlex mesh has largely been abandoned, the great variation in reported outcomes (e.g., mesh exposures in these two papers), highlighted the ongoing problem with polypropylene meshes 15 years earlier.

The 2012 Cochrane review concluded that polyglactin (Vicryl) absorbable mesh in the management of anterior compartment prolapse, as compared with anterior colporrhaphy alone, is more likely to be successful (relative risk [RR] 1.39, 95%; confidence interval [CI] 1.02 to 1.90). Only one case of mesh removal has been reported. A variety of permanent meshes has also been evaluated, and the data from three trials demonstrate that anterior vaginal repair using polypropylene mesh overlay (Figure 8-5) was superior in reducing anterior compartment recurrences on objective assessment, compared with native tissue anterior colporrhaphy (RR 2.14, 95%; CI 1.23 to 3.74).

Transobturator-armed polypropylene meshes, either self-styled or kits, had a lower rate of anterior compartment prolapse on examination, as compared with anterior colporrhaphy alone (RR 3.51, 95%; CI 2.71 to 4.02). After transvaginal polypropylene mesh augmentation, women also had a superior subjective success rate (RR 1.57, 95%; CI 1.18 to 2.07), as compared with anterior colporrhaphy. Further prolapse surgery was not significantly more common after anterior colporrhaphy—14 out of 459 patients (3%), as compared with 6 out of 470 patients (1.3%) after transobturator polypropylene mesh (RR 2.18, 95%; CI 0.93 to 5.10). No difference was detected in individual studies in validated prolapse-specific questions, and metaanalysis was not possible because of the variations in the questionnaires. The surgical time and blood loss were significantly greater in the mesh group, and a tendency toward lower cystotomy rates was reported (0.4% versus 2.7% [RR 0.19, 95%; CI 0.03 to 1.07]) (Altman et al, 2011; Nieminen et al, 2010), de novo dyspareunia (4% versus 8% [RR 0.51, 95%; CI 0.21 to 1.23]), and de novo stress urinary incontinence (SUI) (7.3% versus 11.4% [RR 0.65, 95%; CI 0.4 to 1.07]) after anterior colporrhaphy. (Altman et al, 2011, Sivaslioglu, Unlubilgin, Dolen, 2008; Nieminen et al, 2010) Continence surgery was performed in similar numbers in both groups, 15 of 368 women after anterior colporrhaphy and 12 of 380 women after polypropylene mesh procedure (RR 1.29, 95%; CI 0.63 to 2.63). Metaanalysis of those studies that reported de novo prolapse in the apical or posterior compartment found a lower rate after the anterior colporrhaphy (14 of 147 patients [9.5%]), as compared with transobturator mesh (26 of 148 patients [17.7%]) (RR 0.49, 95%; CI 0.24 to 0.97). Mesh erosions were reported in 41 of 393 women (10.4%) who had an anterior compartment polypropylene mesh, and surgical intervention occurred in 34 of 540 women (6.3%) to correct mesh erosion.

Case 1: Anterior Repair with Midline Fascial Plication

View: Videos 8-2 and 8-3

View: Videos 8-2 and 8-3

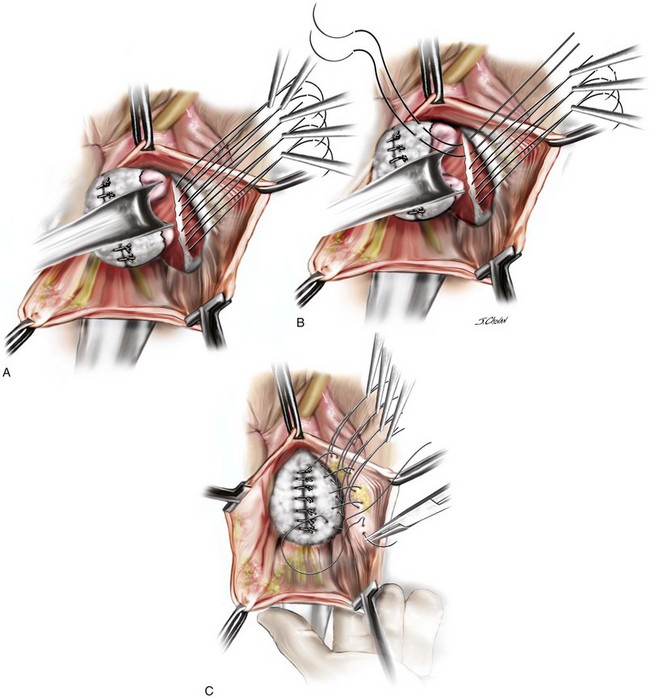

A 55-year-old woman has moderate symptomatic anterior compartment prolapse that approaches the vaginal introitus with straining. She has no other associated urinary or bowel symptoms. Vaginal examination reveals that the anterior compartment extends to within 1 cm of the introitus with the uterus and posterior compartment remaining well supported. With a reduction of the anterior prolapse, no occult stress incontinence is identified. She has undergone no prior pelvic surgeries. The patient has consented to a midline plication of the cystocele (Figure 8-6) with a Kelly-Kennedy plication of the bladder neck (Figure 8-7).

Surgical Steps

The important steps of the procedure are presented as follows (see Figure 8-6):

1. Tenaculums are placed on the midline anterior vaginal wall just below the urethra and at the vaginocervical junction.

2. A midline incision is made in the vaginal mucosa.

3. The authors of this text prefer to use no local anesthetic or hydrodistention, thus allowing a clear demarcation of the planes.

4. Artery forceps are attached to the vaginal mucosa to aid in dissection. An assistant uses forceps to aid in traction to demonstrate the appropriate fascial plane. The surgeon holds Metzenbaum scissors in the dominant hand, and the nondominant hand is positioned under the vaginal mucosa to maximize traction and minimize the risk of “button-holing” the vagina during dissection.

5. With traction and countertraction in the appropriate plane, dissection starts; the fascial tissue is quickly mobilized from the vagina bilaterally. The bladder is also mobilized from the cervix to allow fixation of the fascial repair to the proximal anterior cervix, which, in this case, is well supported.

6. The dissection extends laterally to the inferior pubic ramus, and good paravaginal support is confirmed.

7. Central plication begins at the proximal urethra with a series of interrupted 0 polydioxanone sutures (PDSs). Some surgeons routinely place Kelly-Kennedy plication sutures at the level of the proximal urethra and bladder neck in all patients with urethral hypermobility with no evidence of occult incontinence (see Figure 8-7). These sutures are designed to provide preferential support to the bladder neck over that of the bladder base. The final sutures incorporate the fascia and cervical tissue.

8. A continuous locking delayed absorbable suture closes the vaginal mucosa and includes a central bite in the plicated fascia layer.

9. Cystoscopic examination ensures that the bladder mucosa has not been breached and that the ureters are patent.

10. Vaginal packing and an indwelling catheter are placed. Packing is removed at 6:00 AM the following morning after surgery, and a voiding trial is performed before discharge.

Case Discussion

The traditional well-performed anterior colporrhaphy is ideal in this scenario with an isolated anterior compartment prolapse (see Figures 8-6 and 8-7). The role of routinely performing a Kelly-Kennedy plication in such a setting is controversial and currently based on surgeon preference. The theoretical advantage is that the surgeon may be reducing the rate of de novo development of SUI; however, to date no studies have truly objectified this potential advantage. The incorporation of the fascial repair into the firm proximal anterior cervical tissue (Video 8-2) or durable tissue at the level of the vaginal cuff after hysterectomy serves to connect the level 2 fascial repair; the cervix or vaginal cuff serves as the central cornerstone of the fascial tissue in the upper vagina with the anterior and posterior compartment fascia and the uterosacral, cardinal, and broad ligaments all attaching (Figure 8-8).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree