Chapter 1B Surgical and radiologic anatomy of the liver, biliary tract, and pancreas

Liver

Retrohepatic Inferior Vena Cava

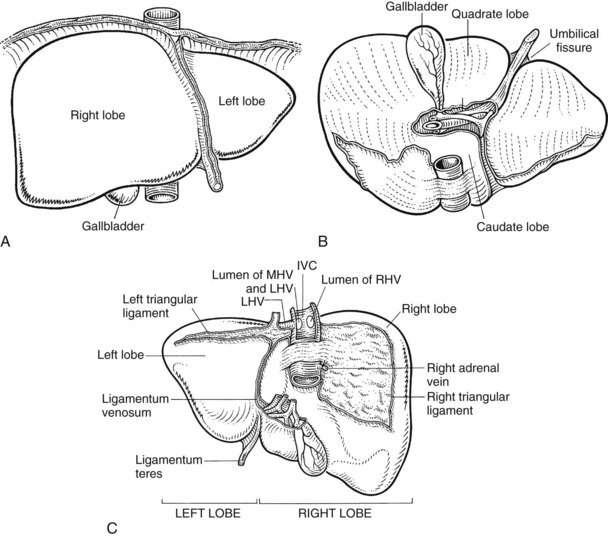

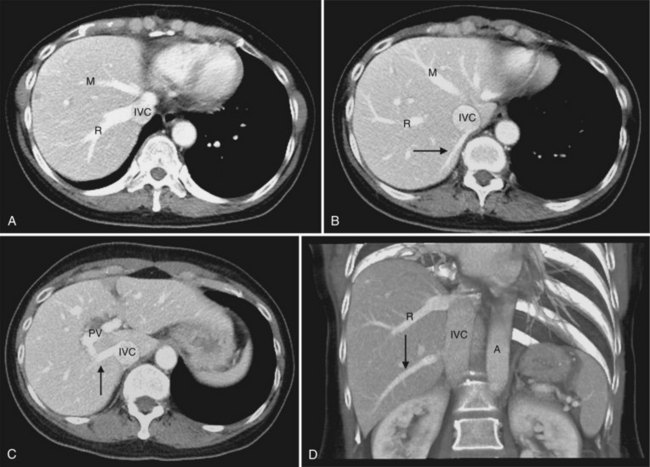

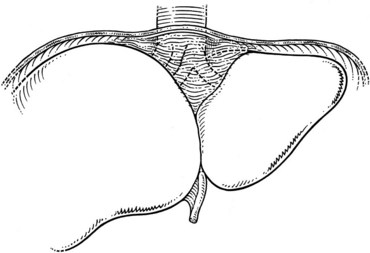

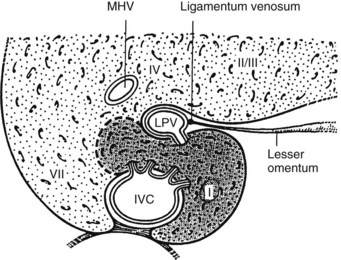

The inferior vena cava (IVC) runs on the right of the aorta on the bodies of the lumbar vertebrae, diverging from the aorta as it passes upward. Below the liver, the IVC lies behind the duodenum and head of the pancreas as a retroperitoneal structure passing upward behind the foramen of Winslow posterior to the right hilar structures of the liver. The renal veins lie in front of the arteries and join the IVC at almost a right angle on the left and obliquely on the right. Behind the liver, the IVC is embraced in a groove on its posterior surface (Figs. 1B.1 and 1B.2). The IVC comes to lie on the right crus of the diaphragm, behind the bare area of the liver; it extends to the central tendon of the diaphragm, which it pierces on a level with the body of T8, behind and higher than the beginning of the abdominal aorta. As the IVC courses upward, it is separated from the right crus of the diaphragm by the right celiac ganglion and, higher up, by the right phrenic artery. The right adrenal vein is a short vessel that enters the IVC behind the bare area (see Fig. 1B.1). There may be a small accessory right adrenal vein on the right that enters into the confluence of the right renal vein and the IVC. The lumbar veins drain posterolaterally into the IVC below the level of the renal veins, but above this level, there are usually no vena caval tributaries posteriorly.

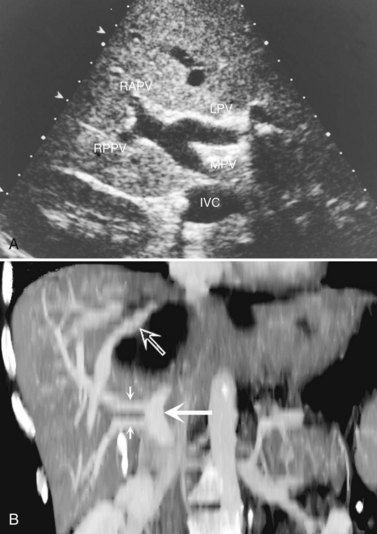

Hepatic Veins

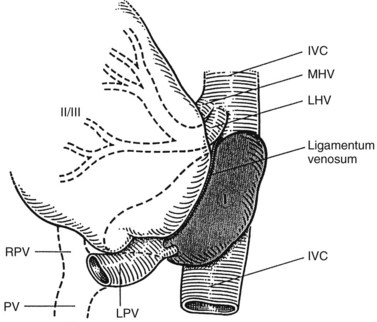

The hepatic veins (Figs. 1B.3 to 1B.5) drain directly from the upper part of the posterior surface of the liver at an oblique angle directly into the vena cava. The right hepatic vein, which is larger than the left and middle hepatic veins, has a short extrahepatic course of approximately 1 cm. The left and middle hepatic veins may drain separately into the IVC but are usually joined, after a short extrahepatic course, to form a common venous channel approximately 2 cm in length that traverses to the left part of the anterior surface of the IVC below the diaphragm (see Figs. 1B.3 and 1B.5). In addition to the three major hepatic veins, there is the umbilical vein, which is single in most cases and runs beneath the falciform ligament between the middle and left hepatic veins; it empties into the terminal portion of the left hepatic vein, although rarely it drains into the middle hepatic vein or directly into the confluence of the middle and left hepatic veins. Additional posteriorly and inferiorly draining hepatic veins, with a short course into the anterior surface of the IVC, are frequent and may be large (see Fig. 1B.4). Hepatic venous drainage of the caudate lobe is directly into the IVC, as described below.

Functional Surgical Anatomy

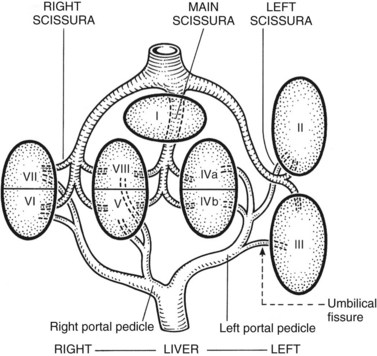

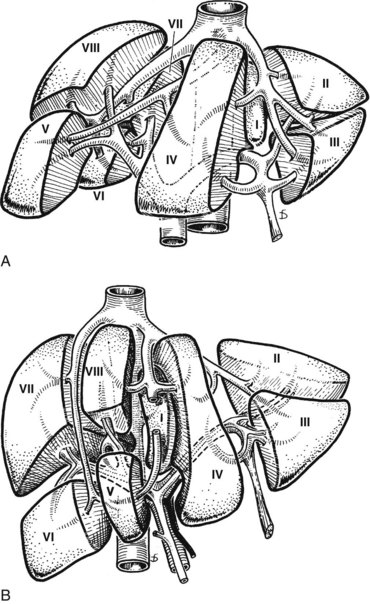

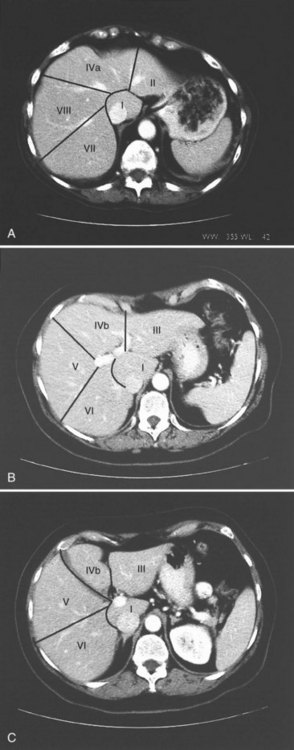

The internal architecture of the liver is composed of a series of segments that combine to form sectors separated by scissurae that contain the hepatic veins (Fig. 1B.6). Together or separately, these constitute the visible lobes described previously. The internal structure has been clarified by the publications of McIndoe and Counseller (1927), Ton That Tung (1939, 1979), Hjörtsjö (1931), Healey and Schroy (1953), Goldsmith and Woodburne (1957), Couinaud (1957), and Bismuth and colleagues (1982); however, the description by Couinaud is the most complete, exact, and useful for the operating surgeon, so it is generally used here. An alternative terminology suggested by a committee of the International Hepato-Pancreatico-Biliary Association (Strasberg et al, 2000) adds little to the understanding or practicality of Couinaud’s description. The main difference is that in the alternative terminology, Couinaud’s sectors are referred to as sections, particularly in describing the anatomy of the left liver (see Chapters 90A to 90F for differences in the terminology of the various hepatic resections).

Essentially, the three main hepatic veins within the scissurae divide the liver into four sectors, each of which receives a portal pedicle, with alternation between the hepatic veins and portal pedicles. The main portal scissura contains the middle hepatic vein and progresses from the middle of the gallbladder bed anteriorly to the left of the vena cava posteriorly. The right and left parts of the liver, demarcated by the main portal scissura, are independent in terms of portal and arterial vascularization and biliary drainage (Fig. 1B.7). These right and left livers are themselves divided into two by the remaining portal scissurae. These four subdivisions are referred to as segments in the description of Goldsmith and Woodburne (1957), but in Couinaud’s nomenclature (1957), they are termed sectors (see Figs. 1B.6 and 1B.7).

The right portal scissura separates the right liver into two sectors: anteromedial (anterior) and posterolateral (posterior). With the body supine, this scissura is almost in the frontal plane. The right hepatic vein runs within the right scissura. The left portal scissura divides the left liver into two sectors, but the left portal scissura is not within the umbilical fissure, because this fissure is not a portal scissura and contains a portal pedicle. The left portal scissura is located posterior to the ligamentum teres and within the left lobe of the liver, along the course of the left hepatic vein. The anterior sector of the left liver—the left medial section, in the terminology of Strasberg and others (2000)—is composed of a part of the right lobe (segment IV), to the left of the main portal scissura, and of the anterior part of the left lobe (segment III; see Figs. 1B.6 and 1B.7). The left posterior sector is the only sector composed of one segment (segment II; the left posterior section in terminology of Strasberg et al).

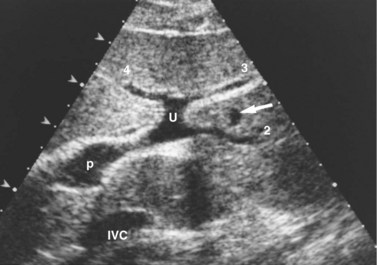

At the hilus of the liver, the right portal triad pursues a short course of approximately 1 to 1.5 cm before entering the substance of the right liver (Fig. 1B.8A). In some cases, the right anterior and posterior pedicles arise independently, and their origins may be separated by 2 cm (see Fig. 1B.8B). In some cases, it appears as if the left portal vein arises from the right anterior branch (see also Fig. 1B.40). On the left side, however, the portal triad crosses over approximately 3 to 4 cm beneath the quadrate lobe, embraced in a peritoneal sheath at the upper end of the gastrohepatic ligament and separated from the undersurface of the quadrate lobe by connective tissue (hilar plate). This prolongation of the left portal pedicle turns anteriorly and caudally within the umbilical fissure, giving branches of supply to segments II and III and recurrent branches to segment IV (Fig. 1B.9; see also Fig. 1B.6). Beneath the quadrate lobe, the pedicle is composed of the left branch of the portal vein and the left hepatic duct, but it is joined at the base of the umbilical fissure by the left branch of the hepatic artery.

The branching of the portal pedicle at the hilus (Fig. 1B.10; see also Figs. 1B.6, 1B.8, and 1B.9), the distribution of the branches to the caudate lobe (segment I) on the right and left sides, and the distribution to the segments of the right (segments V through VIII) and left (segments II through IV) hemiliver follow a remarkably symmetric pattern and, as described by Scheele (1994), allow separation of segment IV into segment IVa superiorly and segment IVb inferiorly (see Fig. 1B.6). This arrangement of subsegments mimics the distribution to segments V and VIII on the right side. The umbilical vein provides drainage of at least parts of segment IVb after ligation of the middle hepatic vein, and it is important in the performance of segmental resection.

The caudate lobe (segment I) is the dorsal portion of the liver lying posteriorly and embracing the retrohepatic IVC. This lobe lies between major vascular structures: On the left, the caudate lies between the IVC posteriorly and the left portal triad inferiorly and the IVC and the middle and left hepatic veins superiorly (Figs. 1B.11 and 1B.12). This portion of the caudate is sometimes referred to as segment IX.

The portion of the caudate on the right varies but is usually quite small. The anterior surface within the parenchyma is covered by the posterior surface of segment IV, the limit being an oblique plane slanting from the left portal vein to the left hepatic vein. Thus, there is a caudate lobe (segment I) with a constantly present left portion and a right portion of variable size (see Figs. 1B.11 and 1B.12).

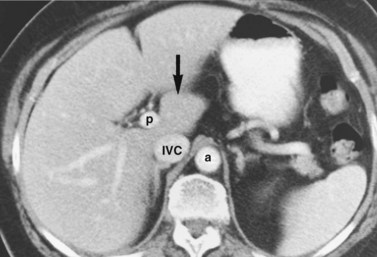

In the usual and common circumstance, the posterior edge of the caudate lobe on the left has a fibrous component, which fans out and attaches lightly to the crural area of the diaphragm; but it extends posteriorly, behind the vena cava, to link with a similar component of fibrous tissue that protrudes from the posterior surface of segment VII and embraces the vena cava (see Figs. 1B.1C and 1B.11). In 50% of patients, this ligament is replaced by hepatic tissue, in whole or in part, and the caudate may completely encircle the IVC and may contact segment VII on the right side; a significant retrocaval component may prevent a left-sided approach to the caudate veins. The caudal margin of the caudate lobe has a papillary process that occasionally may attach to the rest of the lobe via a narrow connection. It is bulky in 27% of cases and can be mistaken for an enlarged lymph node on computed tomography (CT) scan (Fig. 1B.13).

1 The liver is divided into two hemilivers by the main hepatic scissura, within which runs the middle hepatic vein.

2 The left liver is divided into two sectors by the left portal scissura, within which the left hepatic vein runs (see Fig. 1B.6). The posterior sector comprises only one segment, segment II, which is the posterior part of the left lobe. This is the only sector that comprises one segment, referred to as the left posterior section by Strasberg and others (2000). The anterior sector is divided by the umbilical fissure into two segments: a medial segment, the quadrate lobe (segment IV), and a lateral segment (segment III), which is the anterior part of the left lobe.

3 The right liver is divided into two sectors by the right portal scissura, containing the right hepatic vein. Each of these sectors is further divided into two segments: an anterior segment V inferiorly and segment VIII superiorly, and a posterior segment, segment VI inferiorly and segment VII superiorly (see Figs. 1B.6 and 1B.7).

4 Segment I, the caudate lobe, lies posteriorly and embraces the vena cava, its intraparenchymal anterior surface abutting the posterior surface of segment IV and merging with segments VI and VII on the right (Fig. 1B.14; see Fig. 1B.11).

Further details of segmental anatomy important in sectoral or segmental resection are described in Chapter 90A, Chapter 90B, Chapter 90C, Chapter 90D, Chapter 90E, Chapter 90F, Chapter 92 .

Surgical Implications and Exposure

All methods for precise partial hepatectomy depend on control of the inflow vasculature and draining bile ducts and of the outflow hepatic veins of the portion of liver to be excised, which may be a segment, a subsegment, or an entire lobe. The remnant remaining after partial hepatectomy must be provided with an excellent portal venous and hepatic arterial supply and biliary drainage and an unimpeded hepatic venous outflow. Under such circumstances, hepatic regeneration is usually prompt. The classification of the various partial hepatic resection procedures, incisions and exposure, necessary mobilization of the liver, and the methods of control of the structures within the portal triads and of the hepatic veins are described in detail in Chapter 90A, Chapter 90B, Chapter 90C, Chapter 90D, Chapter 90E, Chapter 90F, Chapter 92 .

Biliary Tract

Intrahepatic Bile Duct Anatomy

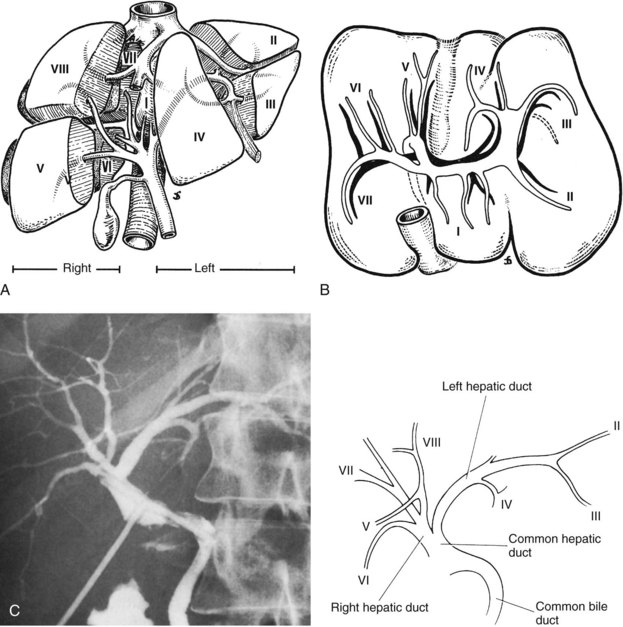

The right and left livers are drained by the right and the left hepatic ducts, whereas the dorsal lobe (caudate lobe) is drained by several ducts that join both the right and left hepatic ducts. The intrahepatic ducts are tributaries of the corresponding hepatic ducts, which form part of the major portal triads that penetrate the liver, invaginating the Glisson capsule at the hilus. Bile ducts usually are located above the corresponding portal branches, whereas hepatic arterial branches are situated inferiorly to the veins. Each branch of the intrahepatic portal veins corresponds to one or two bile duct tributaries that join to form the right and left hepatic ductal systems, converging at the liver hilus to constitute the common hepatic duct. The umbilical fissure divides the left liver, passing between segment III and segment IV, where it may be bridged by a tongue of liver tissue. The ligamentum teres passes through the umbilical fissure to join the left branch of the portal vein (see Fig. 1B.1).

The left hepatic duct drains the three segments—II, III, and IV—that constitute the left liver (Fig. 1B.15). The duct that drains segment III is located slightly behind the left horn of the umbilical recess. It is joined by the tributary from segment IVb to form the left duct, which is similarly joined by the duct of segment II and the duct of segment IVa, where the left branch of the portal vein turns forward and caudally. The left hepatic duct traverses beneath the left liver at the base of segment IV, just above and behind the left branch of the portal vein; it crosses the anterior edge of that vein and joins the right hepatic duct to constitute the hepatic ductal confluence. In its transverse portion, it receives one to three small branches from segment IV.

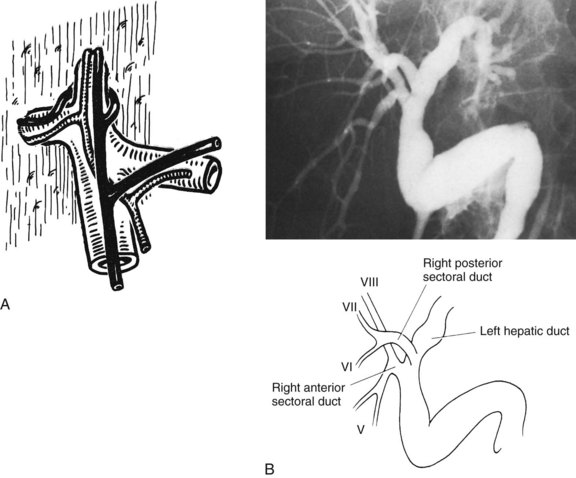

The right hepatic duct drains segments V, VI, VII, and VIII and arises from the junction of two main sectoral duct tributaries (Fig. 1B.16). The posterior or lateral duct and the anterior or medial duct are each accompanied by a corresponding vein. The right posterior sectoral duct has an almost horizontal course and constitutes the confluence of the ducts of segments VI and VII (see Figs. 1B.15 and 1B.16). The duct then runs to join the right anterior sectoral duct, as it descends in a vertical manner. The right anterior sectoral duct is formed by the confluence of the ducts draining segments V and VIII. Its main trunk is located to the left of the right anterior sectoral branch of the portal vein, which pursues an ascending course. The junction of these two main right biliary channels usually occurs above the right branch of the portal vein. The right hepatic duct is short and joins the left hepatic duct to constitute the confluence lying in front of the right portal vein and forming the common hepatic duct.

The caudate lobe (segment I) has its own biliary drainage (Healey & Schroy, 1953

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree