2 Surgical Anatomy of the Pelvis and the Anatomy of Pelvic Support

2-1 Surgical Anatomy of the Anterior Vaginal Wall

2-2 Surgical Anatomy of the Posterior Vaginal Wall

2-3 Anatomy of the Transobturator Space

2-4 Anatomy of the Retropubic Space, Cadaveric Dissection

2-5 Anatomy of the Retropubic Space, Live Surgical Demonstration

2-6 Anatomy of the Bladder and Lower Ureter

Anatomy of the Pelvic Floor

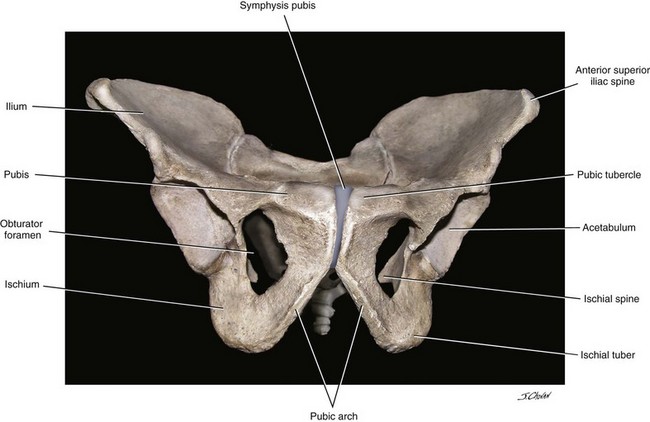

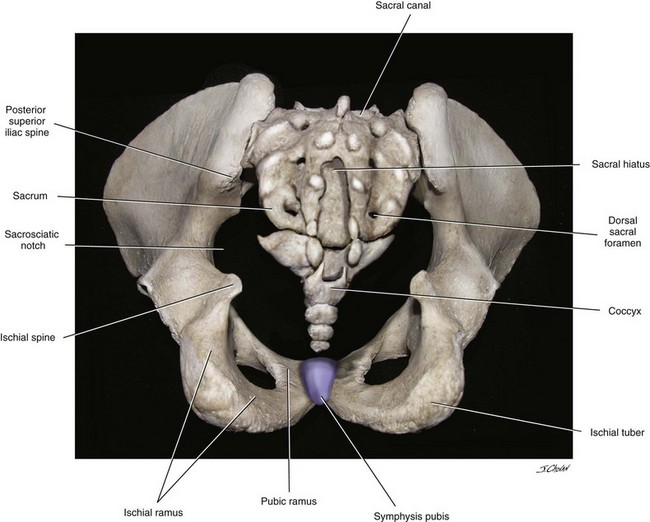

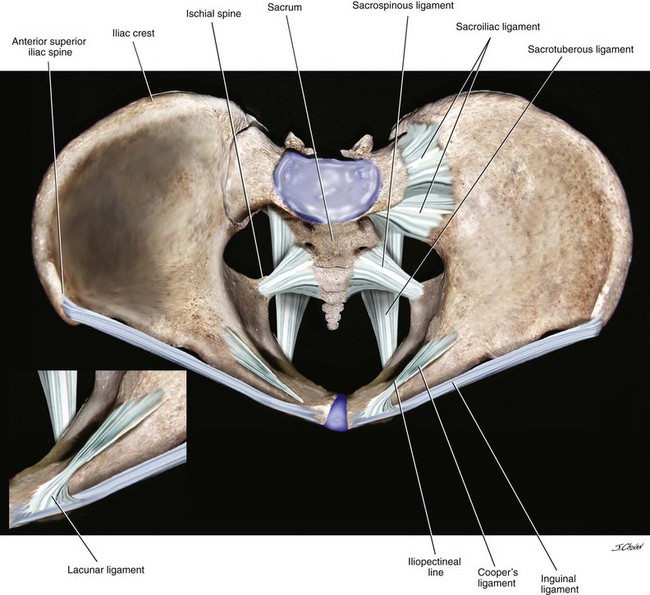

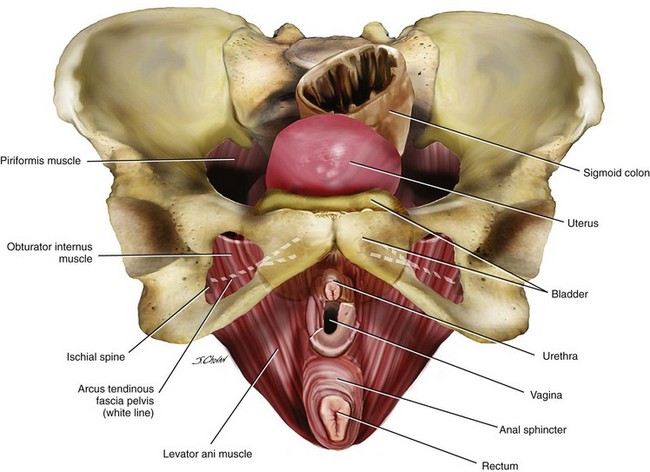

The bones of the pelvis provide the foundation to which all of the pelvic structures are ultimately anchored (Figures 2-1 and 2-2). In the standing position, forces are dispersed to minimize the pressures on the pelvic viscera and musculature and to distribute forces to the bones that are better suited for the long-term, cumulative stresses of daily life. In the upright position, the iliopubic rami are oriented in an almost vertical plane. This orientation directs the pressure of the intraabdominal and pelvic contents toward the bones of the pelvis instead of the muscles and endopelvic fascia attachments of the pelvic floor. The pubic rami are nearly horizontal where they articulate in the midline. The weights of the abdominal viscera and some of the pelvic viscera are inferiorly supported by the bony articulation. Numerous ligaments are attached to the pelvic bones, many of which are used in reconstructive pelvic surgery (Figure 2-3).

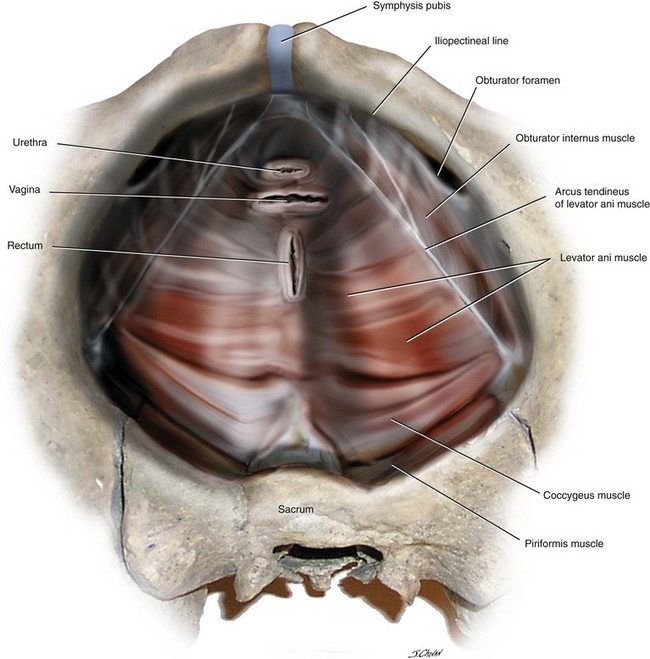

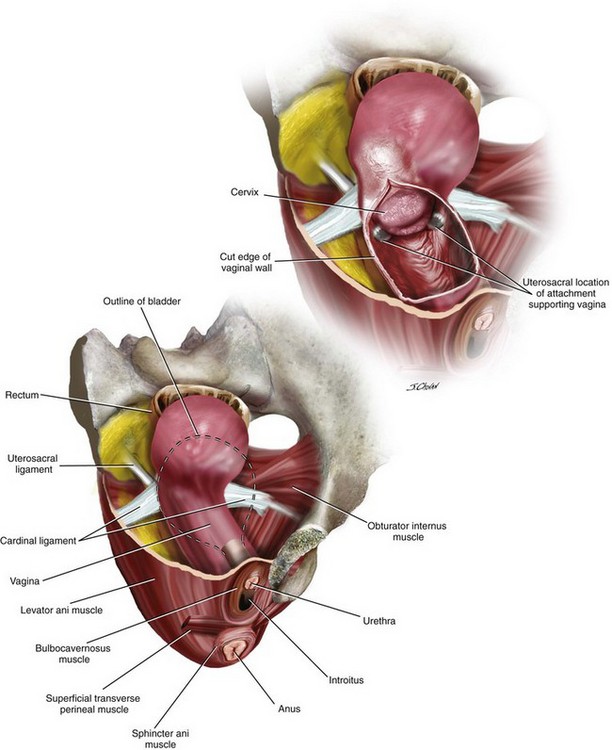

The pelvic floor is made up of muscular and fascial structures that enclose the abdominal-pelvic cavity, the external vaginal opening, and the urethra and rectum (Figures 2-4 and 2-5). The two types of fascial components are parietal and visceral endopelvic fascia. The parietal fascia covers the pelvic skeletal muscles and provides attachment of muscles to the bony pelvis. It is histologically characterized by regular arrangements of collagen. Visceral endopelvic fascia is less discrete and exists throughout the pelvis as a mesh network made of loosely arranged collagen, elastin, and adipose tissue, through which blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerves travel to reach the pelvic organs. Examples of visceral endopelvic fascia are discrete ligaments such as the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments. Figure 2-6 demonstrates the relationship of the vagina to other structures in the pelvis and also illustrates how the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments support the upper vagina.

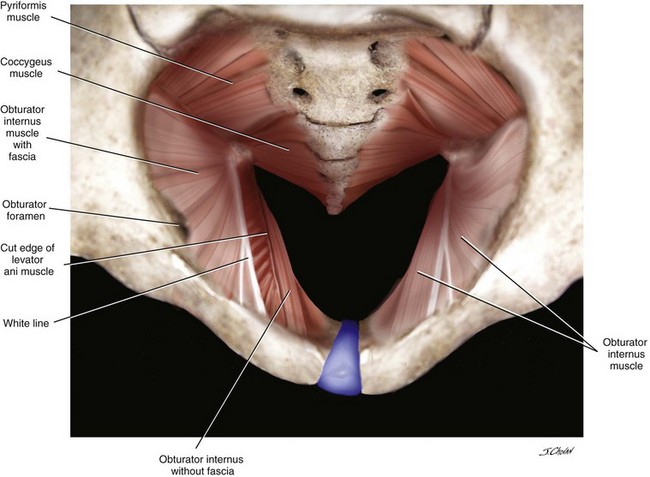

The pelvic side walls are made up of the obturator internus and piriformis muscles. The obturator membrane is a fibrous membrane that covers the obturator foramen (Figure 2-7). The obturator internus originates on the inferior margin of the superior pubic ramus and passes through the lesser sciatic foramen to insert onto the greater trochanter of the femur to rotate the thigh laterally. The piriformis is dorsal and lateral to the coccygeus. It extends from the anterior lateral portion of the sacrum to pass through the greater sciatic foramen and to insert onto the greater trochanter. The pelvic diaphragm consists of the levator ani and coccygeus muscles. The levator ani muscles are divided into the puborectalis, pubococcygeus, and iliococcygeus, which are all skeletal muscles. Other skeletal muscles in the pelvic floor include the external anal sphincter, the striated urethral sphincter, and the superficial perineal muscles (e.g., bulbocavernosus, ischiocavernosus, superficial transverse perinei).

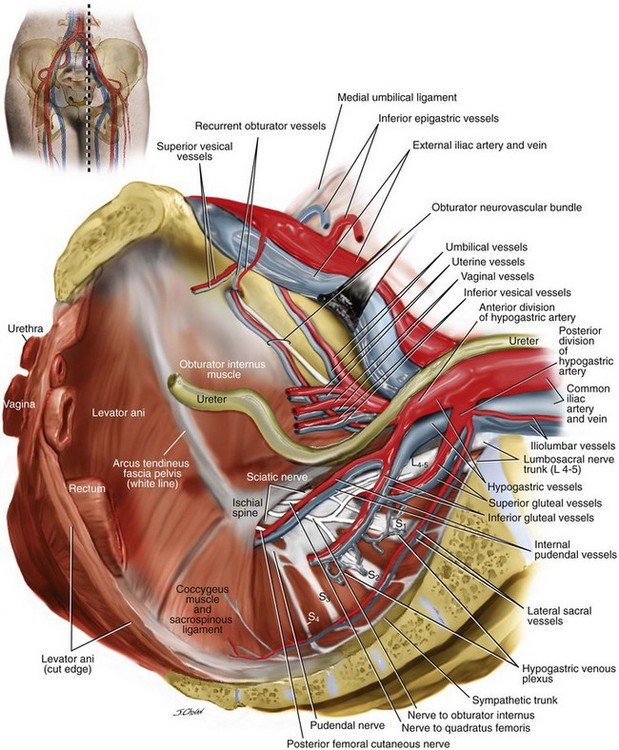

The pelvic diaphragm is a term that has been used to describe the hammocklike structure that these muscles create between the pubic bone from the front and the coccyx from behind. The pelvic diaphragm is attached along the lateral pelvic walls to a thickened linear band of obturator fascia called the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis. This thickened band forms an identifiable line from the ischial spine to the posterior surface of the ipsilateral symphysis pubis. The puborectalis portion of the levator ani originates on the posterior inferior pubic ramus and arcus and passes posteriorly, forming a sling around the vagina, rectum, and perineal body to form the anorectal angle. Some muscle fibers may blend with the muscularis of the vagina, rectum, and external anal sphincter (see Figure 2-5). The pubococcygeus has a similar origin but inserts in the midline onto the anococcygeal raphe and the anterolateral borders of the coccyx. The iliococcygeus originates along the arcus tendineus from the back of the pubis to the ischial spine and inserts on the anococcygeal raphe to form the levator plate. The space through which the rectum, vagina, and urethra pass is called the genital hiatus (see Figure 2-7). The coccygeus muscle, who some would consider as part of the levator ani complex, makes up the posterior part of the pelvic floor and also plays a role in support. It originates on the ischial spine, overlies the sacrospinous ligament, and inserts on the lateral lower sacrum and coccyx. As one ages, the coccygeus becomes thinner and more fibrous, often blending with the sacrospinous ligament. At times, distinguishing the two is difficult because of the fact that they have the same origin and insertion. The coccygeus sacrospinous ligament complex (C-SSL) is a very common anchoring point for a variety of prolapse repairs that are discussed and illustrated throughout this text. Appreciating the close proximity of the many vascular structures and nerves to the C-SSL is extremely important (Figure 2-8). Posterior to the complex are the gluteus maximus muscle and the ischiorectal fossa. The pudendal nerves and vessels lie directly posterior to the ischial spine, and the sciatic nerve lies superior and lateral to the ischial spine. An abundant vascular supply, which includes the inferior gluteal and the hypogastric venous plexus, also lies superior to the ischial spine. The C-SSL complex can be exposed via a posterior perirectal dissection, as well as by anterior paravaginal dissection. The ability of the surgeon to palpate and identify this structure safely is mandatory to avoid significant bleeding or nerve damage.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree