Sports Hernia

L. Michael Brunt

Introduction

The topic of sports hernia has gained increasing attention in recent years due to a number of high profile athletes who have undergone surgery for this problem. Although athletic groin injuries are very common in sport, it is important to understand that the condition referred to as a “sports hernia” (which is more appropriately described by the term athletic pubalgia) represents a small percentage of groin injuries that occur in athletes. Moreover, groin injuries in athletes represent a challenging problem both from a diagnostic and therapeutic standpoint because of the broad differential diagnosis, subtle physical examination findings, anatomic complexity of the pelvic and groin region, and the multiplicity of causes. These injuries may result in a significant loss of playing time and, therefore, can be a source of frustration for the athlete, athletic trainers, and treating physicians. In this chapter, the clinical presentation and diagnostic approach to the athletic groin will be reviewed and an overview of repair techniques and surgical outcomes will be presented.

Background

Sports that have repetitive twisting, turning and kicking motions at high speed such as soccer, ice hockey, and football are associated with a significant incidence of groin injury. In one study from Scandinavia, groin injuries occurred in 5% to 28% of soccer players and accounted for 8% of all injuries over one season. Similarly in a study of Swedish hockey players, groin injuries accounted for approximately 10% of all injuries. Unlike many other injuries in sport, most of these are soft tissue injuries and do not typically result from direct physical contact.

A number of risk factors have been identified that may increase an athlete’s risk of groin injury. In one study of National Hockey League players, Emery and colleagues found that fewer than 18 sport-specific training sessions in the off-season, a history of previous groin or abdominal strain, and veteran player status were all associated with an increased risk of groin injury. Another study from the NHL by Tyler et al. showed that hockey players with an adductor to abductor strength ratio of less than 80% were 17 times more likely to sustain an adductor strain. Moreover, adductor strengthening reduced the incidence of injury from 3.2/1,000 to 0.71/1,000 player game exposures.

Differential Diagnosis

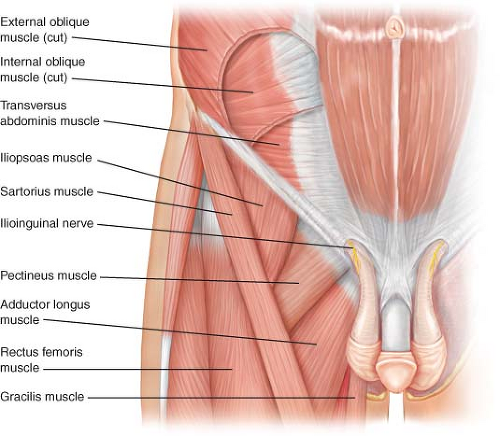

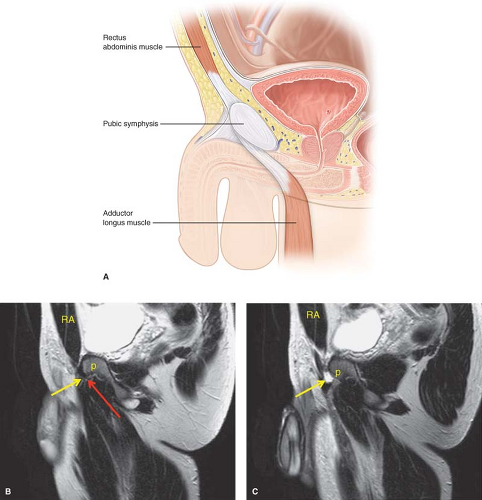

In order to differentiate the various causes of athletic groin pain, an understanding of the complex anatomy of the musculoskeletal relationships around the pelvis as illustrated in Figure 20.1 is essential. The pelvis acts like a fulcrum or joint around which the powerful abdominal and thigh muscles act. The rectus abdominis inserts on the anterior pubis and its aponeurosis is continuous with that of the adductor longus as shown in Figure 20.2 on both the schematic illustration and sagittal MRI sequences.

The differential diagnosis of groin pain in the athlete is broad and includes injuries to the bony pelvis, muscular strains, hip injuries, and even non-athletic causes. An outline of the principal conditions to be considered in a differential diagnosis is listed below.

Differential diagnosis of groin pain in athletes:

Pelvis: Stress fracture, traumatic fractures or contusions, osteitis pubis

Hip: Labral tear, femoral acetabular impingement, osteoarthritis

Thigh: Muscular strains—adductor group, hip flexors

Abdominal muscular strains: Rectus abdominis, obliques

Sports hernia/athletic pubalgia

Inguinal hernia

Non-athletic causes (ovarian cyst, endometriosis, inflammatory bowel disease)

Stress fractures are most commonly seen in endurance runners and can affect the inferior pubic ramus or femoral neck region. Osteitis pubis is a condition in which there is midline pubic symphysis pain that is probably related to overuse and abnormal biomechanics around the pubis. Treatment consists of reduced activity, physical therapy, and corticosteroid injections for selected cases. Muscular strains can occur in any of the muscle groups around the hip and pelvis but most commonly involve the adductor muscle group. These may be acute or chronic and typically resolve with conservative management. In one study of sports groin injuries, adductor longus strains accounted for 62% of all sports injuries. Hip injuries should always be excluded in the athlete with groin pain, particularly labral tears and femoral acetabular impingement. Inguinal

hernias are included among the possible diagnoses but are rarely present. Finally, non-athletic causes of groin pain should be considered especially in female athletes.

hernias are included among the possible diagnoses but are rarely present. Finally, non-athletic causes of groin pain should be considered especially in female athletes.

Diagnostic Evaluation

The evaluation of the athlete with groin pain begins with a detailed history and physical examination. The following points are important to elicit in the history:

Onset of the pain (acute vs. chronic)

Precise location of the pain

Is the pain diffuse or radiating?

Factors that aggravate or alleviate the pain

Possible mechanism of injury involved

History of prior injury or any change in training regimen

In a classic sports hernia type athletic pubalgia, athletes complain of chronic lower abdominal and inguinal pain that is most pronounced during the extremes of motion. Specifically, symptoms are aggravated by sudden turns or cutting movements, propulsive skating movements in hockey, and kicking in soccer or football. Importantly, the pain limits sudden accelerating movements which can be the difference in success and failure for high level athletic performance. Other symptoms that may be associated include pain with coughing or sneezing and adductor symptoms. The onset is often insidious with no clear precipitating event and fails to resolve with conservative management.

Physical examination findings are often subtle and include tenderness in the medial inguinal canal/distal lateral rectus at the right lateral pubis as shown in Figure 20.3. Other findings may include a dilated external ring, a palpable gap over the inguinal canal, and pain with resisted trunk rotation (Fig. 20.3B) or resisted sit-ups. Importantly, there is no evidence of a true inguinal hernia bulge.

Imaging is indicated for excluding other causes of groin pain. Plain pelvis x-rays may be useful for screening hip and bony pelvis abnormalities. The preferred imaging modality in North America is a pelvic MRI which provides details about the various muscular anatomy, tendons, and bony structures around the pelvis. Findings on MRI may include parasymphyseal edema on the side of the injury (Fig. 20.4), a tear in the distal rectus or proximal adductor longus aponeurosis adjacent to the pubis (Fig. 20.5), and evidence of chronic adductor tendinopathy (Fig. 20.6). Some groups have used dynamic ultrasound

to assess the integrity of the posterior inguinal floor, but this modality requires considerable experience and is very operator dependent.

to assess the integrity of the posterior inguinal floor, but this modality requires considerable experience and is very operator dependent.

Figure 20.3 Examination of inguinal floor for athletic pubalgia. A: The floor is examined supine and durign a sit-up for areas of weakness and tenderness. B:

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

|