Frederick A. Moore

DEFINITION

■ Splenectomy is defined as the surgical removal of the spleen.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS/INDICATIONS

■ Traumatic rupture

■ Autoimmune disorders

■ Red blood cell disorders

■ Genetic disorders

■ Lymphomas/leukemias/myeloproliferative disorders

■ Vascular disorders

■ Idiopathic/iatrogenic

■ Miscellaneous (abscesses, tumors, cysts)

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

■ A thorough history should be performed prior to surgery, including a detailed past medical history, all signs and symptoms of disordered bleeding and liver failure, as well as a history of abdominal pain or constitutional symptoms. A list of medications, allergies, and personal and family histories of bleeding, clotting disorders, and cancers should be noted.

■ A complete physical exam of the patient should be done and all patients should be examined for signs of portal hypertension or liver failure as well as the presence or absence of splenomegaly.

■ Patients presenting with splenic trauma have variable clinical presentations determined by the severity of injury, ranging from mild abdominal pain with hemodynamic stability to peritonitis and hemorrhagic shock with complete cardiovascular collapse. This hemodynamic instability can be immediate upon presentation or days later in the case of a delayed rupture.

■ Hematologic conditions such as leukemia present with a patient history of purpura, epistaxis, petechiae, gingival bleeding, hematuria, gastrointestinal bleeding, myalgia, or fatigue. Although now a rare indication for splenectomy, patients with lymphomas and myeloproliferative disorders present with diffuse lymphadenopathy, constitutional symptoms, pancytopenia, abdominal pain, splenomegaly, or early satiety.

■ Patients with hemoglobinopathies and hereditary disorders present with jaundice, abdominal pain, or splenomegaly. Alternatively, they may be asymptomatic and incidentally identified due to an abnormal laboratory value obtained for a different indication.

■ Patients with hereditary spherocytosis (HS) benefit from splenectomy. Sequestration of the defective red blood cells (RBCs) results in splenomegaly in 75% of affected patients.1 Splenectomy eliminates or improves anemia in patients with moderate HS and eliminates the need for regular transfusions in patients with the severe form of the disease.2,3 These patients often receive splenectomies in childhood to alleviate symptoms and long-term sequela of the disease including skeletal abnormalities and repeated need for blood transfusion. In mild HS, the purpose of splenectomy is to prevent the production of bilirubin gallstones (a common complication that has an increased prevalence with age). In these cases, splenectomy is combined with a cholecystectomy.

■ Splenectomy for hematologic disorders such as idiopathic thrombocytopenia (ITP) is a result of failed medical management to control thrombocytopenia or abdominal pain associated with splenomegaly. Most of these patients will be referred to a treating hematologist. Medical management is the first-line treatment for ITP and most patients initially respond to glucocorticoids. However, in one series, only 39% of prednisone-treated patients achieve complete remission, and only one-half of these patients have sustained remission beyond 6 months of cessation of maintenance therapy.4 Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) can also be used as first-line treatment and can increase the platelet count in over 75% of patients within 5 days of treatment.5 However, it is not a long-term cure. It is reserved for those patients with life-threatening bleeding and intracranial hemorrhage and those preparing for splenectomy or other surgical procedures. Otherwise, splenectomy is reserved for patients with symptomatic thrombocytopenia following glucocorticoid administration for at least 8 weeks and having a platelet count persistently less than 30,000/μL. Splenectomy is also indicated in patients who recur after cessation of therapy.

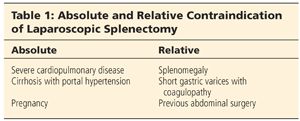

■ Splenectomies may be performed via open or laparoscopic technique. The approach is determined by the disease process and clinical stability of the patient. Absolute and relative contraindications for laparoscopic splenectomy are listed in Table 1.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

■ All patients with a known or suspected hematologic, autoimmune, or myeloproliferative disorder should have a blood smear or bone marrow analysis as needed and a hematologist fully involved in the patient’s evaluation and treatment plan.

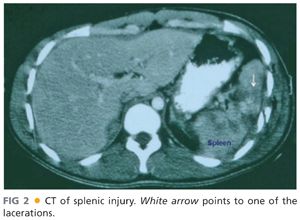

■ Computed tomography (CT) scan is the ideal imaging modality for splenic disorders and is a crucial part of planning for the operating room (OR). CT has the capability for determining the size of the spleen, the anatomy and size of the splenic vascular supply, the relationship of the spleen to surrounding organs, and potential locations of accessory spleens in the abdomen (FIG 1). For stable trauma patients, it can accurately identify the extent of splenic injury (FIG 2).

■ Ultrasound is a noninvasive modality for the examination of splenomegaly and portal hypertension. In the setting of a trauma, focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST) has become an accepted screening tool to diagnose intraperitoneal blood (FIG 3).

■ Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spleen is an excellent method for evaluating focal lesions as well as aid in the detection and differential diagnosis of peri- and intrasplenic tumors.6

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

■ Certain patients with autoimmune disorders will be treated with prolonged courses of glucocorticoids. It is important to consider administering appropriate stress-dose steroids intraoperatively, with rapid tapering postoperatively.

■ Blood products should be ordered and available intraoperatively. If the need for transfusion arises, it should be given after ligation of the splenic artery, provided the splenectomy is performed for hematologic disorders.

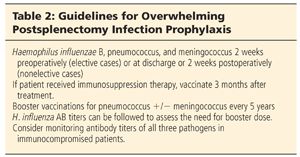

■ For all elective cases, vaccinations against the encapsulated organisms (Hemophilus influenza B, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Neisseria meningitidis) should be administered prior to surgery. For emergent cases, vaccinations should also be administered. Timing of vaccination is debated, but 2 to 4 weeks postoperatively is recommended, although for trauma patients, just prior to discharge is acceptable due to a high incidence of patients not returning for postinjury clinic appointments. This is to prevent the incidence of overwhelming postsplenectomy infection (OPSI). It is the most feared complication of splenectomy. OPSI is the development of a fulminant, rapidly fatal bacterial infection following the removal of the spleen. The current incidence of OPSI in the first 2 years postsplenectomy is estimated to be 0.9% for adults and 5% for children.7 Current guidelines for vaccination to prevent OPSI are listed in Table 2.

■ All patients should be given a prophylactic dose of antibiotics to cover skin flora within 60 minutes of making the skin incision in the OR. Nasal or oral gastric tubes should be inserted once the patient is under anesthesia to decompress the stomach and aid in visualization. This will often be left in postoperatively for 24 to 48 hours to prevent gastric distention and subsequent disruption of the ligated short gastric vessels.

■ Laparoscopic splenectomy is the operation of choice for most elective splenectomies. However, other options include hand-assisted or open approaches. Indications for conversion from laparoscopy to an open procedure include intolerability or inability to insufflate the peritoneum, uncontrollable coagulopathy or hemorrhage, massive splenomegaly that is unable to be placed in the extraction bag, or need for another procedure.

■ In cases of massive splenomegaly or portal hypertension, preoperative embolization of the splenic artery by interventional radiology will decrease the amount of blood loss and may aid in the technical aspects of the procedure. Embolization of the splenic artery causes decreased perfusion and thereby results in involution of the spleen, making mobilization of the spleen technically easier.

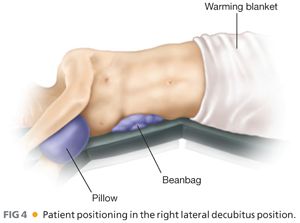

POSITIONING

■ Patients undergoing laparoscopic splenectomy can be positioned supine or in the right lateral decubitus position. In the latter position, the beanbag or kidney rest is placed to maximize exposure between the costal margin and iliac crest. The table may also be flexed to assist in widening this space. Ensure that all pressure points are properly padded and the shoulders, extremities, and spine are in comfortable, neutral positions (FIG 4).

■ For open splenectomies, most patients are placed in a supine position, with both arms extended, and a midline laparotomy incision is made. Indeed, in the case of an exploratory laparotomy in the setting of a trauma, this is the recommended approach as the surgeon will need to evaluate the entire abdomen for other injuries. An additional option in isolated nontraumatic open cases is to make a left subcostal incision.

TECHNIQUES

OPEN SPLENECTOMY

Incision

■ Prior to incision, ensure adequate monitoring and intravenous access is obtained in preparation for potential bleeding. An arterial line is not mandatory but is recommended. A nasogastric (NG) tube should be placed for optimal gastric decompression, which will be imperative for visualization of the spleen.

■

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree