Follow-up of the large numbers of patients undergoing bariatric surgery poses problems for surgical programs and for internists who care for morbidly obese patients. Early surgical follow up is concentrated on the perioperative period to ensure healing and care for any surgical complications. It is especially important to treat persistent vomiting to avoid thiamine deficiency. Subsequently, monitoring weight loss and resolution of comorbidities assumes more importance. Identification and management of nutritional deficiencies and other unwanted consequences of surgery may become the responsibility of internists if the patient no longer attends the office of the operating surgeon. The long-term goal is to avoid weight regain and deficiencies, especially of protein, iron and vitamin B12, and calcium and vitamin D. Abdominal pain and gastrointestinal dysfunction should be investigated promptly to exclude or confirm such conditions as small bowel obstruction or gallstones. Good communication between bariatric surgeons and internal medicine specialists is essential for early and accurate identification of problems arising from bariatric surgery.

Historically, it was customary for patients requiring surgery to be referred to a surgeon by an internist. The surgeon performed the procedure requested by the referring physician, and surgical follow-up was limited to ensuring that the patient had healed from the effects of the surgery and that perioperative complications were adequately managed. The long-term management of the underlying disease remained the responsibility of the internist. A major change in emphasis has occurred as more and more benign diseases requiring lifelong attention are managed by surgical therapy. The process began with the long-term studies on the outcome of surgery for peptic ulcer disease originating in centers such as Leeds, England, in the middle of the twentieth century. During the same time period Ronald Belsey in Bristol, England, inculcated the same concept in generations of thoracic surgeons treating hiatal hernia and reflux disease. It is no accident that these principles began to be learned shortly after the introduction of the British National Health Service in 1948. The radically different structure of health care in the United States is not as amenable to long-term follow-up of patients because there is no central way of collecting the data, and repetitive visits for many years are viewed as unnecessary and costly unless driven by specific symptoms or risk factors. Nevertheless, in conditions in which surgical therapy induces permanent alteration in physiology, there is increasing recognition that the surgeon is in a good position to understand the pathophysiology of the condition and the physiologic consequences of the operative procedure and that the surgeon is the ideal person to provide long-term follow-up. There is no area of medical practice where this is truer than for bariatric surgery. The major societies promoting the science and practice of bariatric surgery, notably the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS), have been leaders in the surgical community in creating a culture where long-term structured follow-up of patients after bariatric surgery is the responsibility of the operating surgeon. This ideal goal is still a work in progress. It is inevitable that many patients undergoing bariatric surgery will eventually be cared for by other physicians, and knowledge of the anatomy and physiology of bariatric procedures is essential for modern internists. Good communication links with bariatric surgeons also facilitates the care of this challenging population of patients.

Definitions

This review concentrates on the 3 major bariatric procedures commonly performed in this country for severe obesity and its comorbidities. The most commonly performed operation is the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), which accounts for about 65% of contemporary procedures, and laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB) accounts for about 25%. The remaining 10% include procedures such as the duodenal switch (DS) or its precursor biliopancreatic diversion (BPD) and, more recently, the sleeve gastrectomy. The details of these procedures are described elsewhere in this issue and therefore not be repeated here. However, primary care providers should have a broad understanding of the principles of these different procedures because each produces a different spectrum of complications and side effects.

Follow-up after surgery can be conveniently grouped into 3 phases, namely short term (up to 3 months from surgery), medium term (3–24 months), and longer term (>2–5 years). These definitions are to some extent arbitrary, but the principles are broadly agreed upon.

Short-term follow-up

Short-term follow-up is largely aimed at ensuring that the patient heals without any perioperative complications. This is so fundamental that all postoperative visits within 90 days of any surgical procedure are regarded by third party payers as being within the global period covered by the surgeon’s fee. During this period, the focus of the visits is to monitor the healing of incisions and to ensure that there are no leaks and that function in the new stomach reconstruction is adequate to avoid critical problems such as dehydration and vitamin deficiency. Patients are typically scheduled for routine postoperative visits 2 and 6 weeks after discharge from hospital.

Serious perioperative complications are managed initially as inpatients by the surgeon. The most serious complications are leaks from the anastomosis or other suture lines (about 1%–2% in contemporary series) and pulmonary embolism (less than 1%). Patients recovering from such complications are followed up much more closely and may require prolonged courses of intravenous (IV) antibiotics and possibly total parenteral nutrition and follow-up computed tomography (CT)-guided drain placement. Taking care of drainage tubes and managing open wounds then dominate the early postoperative visits. Pain management, physical therapy, and nutritional supervision also require much more attention in such patients.

In the absence of such serious complications, the problems arising during the first 3 months after surgery typically are classified into 3 categories:

Incisional Problems

The incidence of surgical site infection (SSI) may be 10% or even higher after open bariatric surgery Risk factors include high body mass index (BMI), poorly controlled diabetes, smoking, and the duration (and indirectly, the difficulty) of the procedure. Timely administration of appropriate antibiotics (less than 60 minutes before making the skin incision and discontinuance within 24 hours of surgery) has reduced the incidence to some extent. Tight control of blood sugar and avoidance of hypothermia intraoperatively and administration of a high fraction of inspired oxygen (F io 2 ) in the recovery ward immediately after surgery may also help reduce the risk of SSI, but the value of these measures remains controversial. SSI typically develops 5 to 10 days after surgery and is rarely obvious before the patient goes home, typically on postoperative day 3 to 5. Patients often present a few days after discharge with redness or induration in part of the incision, associated with systemic signs of fever, tachycardia, and worsening gastrointestinal (GI) function. In contrast, laparoscopic incisions are rarely complicated by infection. However, when a circular stapler is used to fashion the gastrojejunal (GJ) anastomosis, the surgeon must enlarge one of the trocar sites to permit introduction of the stapling cartridge, and after the cartridge is fired, it may be difficult to avoid contaminating the wound edge as it is removed from the abdomen. Infection of that particular port site occasionally occurs in that situation.

Early GI Dysfunction

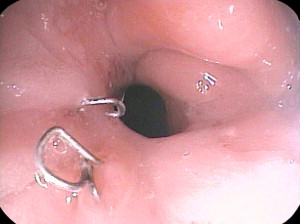

The narrow gastric pouch after RYGB or sleeve gastrectomy is restrictive at the beginning, and patients can usually tolerate only clear liquids in small quantities at first. Patients are usually given written instructions to guide the gradual increase in the quantity and range of foods they can tolerate. Patients who do not receive or who do not understand such instruction have a high incidence of vomiting postoperatively. Many patients will experience a few episodes of vomiting if they relax the vigilance with which they increase their dietary intake, and some vomiting is probably inevitable as they learn how to cope with a sensation of fullness, which is a novel experience for most bariatric patients. However, in well-instructed and supported patients, it should be rare. Rather than berate the patient for failure of compliance, or attribute vomiting to persistence of a psychological compulsion to eat large quantities quickly, the physician should consider organic causes, namely a stricture. Some degree of stricturing of the GJ anastomosis is common, and usually resolves with time (less than 3 months) and can be managed by going back to softer or liquid foods. A more severe stricture may be because of an ulcer at the anastomosis, and the physician should inquire about consumption of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or large pills or resumption of smoking. Endoscopy typically reveals an ulcer with visible suture material or staples ( Fig. 1 ). Such strictures are easy to dilate, and 1 or 2 dilations generally are sufficient.

The effects of persistent vomiting may be serious, and vomiting may lead to dehydration and renal impairment. This is usually quickly reversible. A rare but much more serious result of persistent vomiting is Wernicke encephalopathy, which is a consequence of thiamine deficiency. It is characterized by changes in mental status (confusion, short-term memory loss), ataxia, and eye movement signs such as nystagmus and ophthalmoplegia. A recent review described 104 cases, with the majority presenting between 1 and 3 months postoperatively. Confirmation by measuring thiamine levels is not routinely done because blood levels are not always subnormal and are rarely available in time to help the diagnosis. Therefore, this diagnosis should be considered in any patient after recent bariatric surgery who presents with changes in mental status, and it should be remembered that administration of dextrose can worsen the situation. Thus immediate administration of thiamine (100 mg IV or intramuscular) is advisable in any patient reporting frequent vomiting in the first few months after bariatric surgery.

Bile vomiting early after bypass surgery is almost unheard of unless there is a major problem with the reconstruction, such as a mechanical obstruction just beyond the enteroenterostomy or even the “Roux-en-O” pattern, where the biliopancreatic limb was mistaken for the Roux limb and connected to the stomach. Bile vomiting is highly likely to mandate a reoperation, and if the original surgeon is reluctant to undertake it, the internist should refer the patient to a major referral center.

Lower GI tract dysfunction may result in diarrhea, and if the diarrhea is persistent, it is important to check for Clostridium difficile toxin. Diarrhea is common after malabsorptive operations, such as the DS, whereas constipation is common after gastric bypass. These complications tend to resolve with time as dietary intake becomes more varied. Simple over-the-counter remedies are occasionally needed in this situation.

Management of Coexisting Medical Problems

Many patients are already on treatment for comorbid problems such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, depression, and other conditions unrelated to obesity. There is often confusion about how these conditions should be managed, because surgeons may not be comfortable adjusting the doses of antihypertensives or hypoglycemic agents and the internist may not be aware of the physical restrictions imposed by different kinds of reconstruction.

In general, swallowing large pills within the first 6 weeks of surgery should be avoided. Necessary medications should therefore be taken in crushed or liquid form. Slow-release medications must not be crushed, and they should be replaced by the equivalent in divided doses of standard pills. Potassium tablets are notably toxic to the esophagus and the narrow gastric pouch. However, because fluid intake is so restricted early after bariatric surgery, the diuretic therapy may be withheld and potassium supplements may therefore be unnecessary. Bariatric patients commonly use NSAIDs because obesity markedly contributes to degenerative joint disease. In addition, antiinflammatory medications are particularly effective in obesity possibly because it is a proinflammatory state. Liquid ibuprofen avoids the problem of a large pill becoming lodged in the esophagus or gastric pouch, but it does not avoid the systemic effect of NSAIDs on gastric mucosa.

The need for antihypertensives frequently diminishes abruptly after surgery. Most patients may safely discontinue them for a few weeks. In approximately 50% of cases, hypertension is abolished for a long term, but there is a tendency for blood pressure to rise some years afterward despite early normalization as weight is lost. Blood glucose level tends to be reduced rapidly after surgery, and almost 80% of patients will have long-term remission of type 2 diabetes mellitus. In the immediate postoperative period, caloric intake is so low that hypoglycemia might be precipitated by regular doses of medications. Patients taking insulin are usually discharged on half their preoperative dose, with instructions about how to adjust the dose relative to the fasting and postprandial blood glucose levels. Early follow-up with an internist or endocrinologist is arranged.

Weight loss after gastric bypass is rapid in the first few weeks, often averaging 0.5 kg per day in the beginning. After adjustable gastric banding, the weight loss is typically much slower. Adjustments to the gastric band begin about 6 weeks after surgery and every 3 to 8 weeks thereafter until the correct degree of restriction is achieved. The ideal status is when the patient is conscious of a slight degree of restriction but can eat a wide range of foods while being satisfied with smaller quantities. Adjustments are performed by injecting the subcutaneous port with saline using a Huber-type needle. The adjustments are often performed in the surgeon’s office, but some programs recommend fluoroscopically guided band adjustments.

Laboratory studies may be ordered after the first 2 to –3 months to follow up the patient’s nutritional status. A typical panel should include a complete blood count to check for hemoglobin (Hb) level and mean corpuscular volume (MCV); a comprehensive metabolic panel should include the level of albumin and liver enzymes, level of iron and total iron binding capacity, and levels of vitamin B 12 , folate, calcium, intact parathyroid hormone (PTH), and 25-hydroxy vitamin D (25-OH vitamin D). A lipid panel is added if the patient had dyslipidemia preoperatively, and HbA1c levels are measured in patients with diabetes. These parameters should be followed up sequentially over several years, as individual abnormalities may be insignificant but a worsening trend implies the need for corrective action.

Short-term follow-up

Short-term follow-up is largely aimed at ensuring that the patient heals without any perioperative complications. This is so fundamental that all postoperative visits within 90 days of any surgical procedure are regarded by third party payers as being within the global period covered by the surgeon’s fee. During this period, the focus of the visits is to monitor the healing of incisions and to ensure that there are no leaks and that function in the new stomach reconstruction is adequate to avoid critical problems such as dehydration and vitamin deficiency. Patients are typically scheduled for routine postoperative visits 2 and 6 weeks after discharge from hospital.

Serious perioperative complications are managed initially as inpatients by the surgeon. The most serious complications are leaks from the anastomosis or other suture lines (about 1%–2% in contemporary series) and pulmonary embolism (less than 1%). Patients recovering from such complications are followed up much more closely and may require prolonged courses of intravenous (IV) antibiotics and possibly total parenteral nutrition and follow-up computed tomography (CT)-guided drain placement. Taking care of drainage tubes and managing open wounds then dominate the early postoperative visits. Pain management, physical therapy, and nutritional supervision also require much more attention in such patients.

In the absence of such serious complications, the problems arising during the first 3 months after surgery typically are classified into 3 categories:

Incisional Problems

The incidence of surgical site infection (SSI) may be 10% or even higher after open bariatric surgery Risk factors include high body mass index (BMI), poorly controlled diabetes, smoking, and the duration (and indirectly, the difficulty) of the procedure. Timely administration of appropriate antibiotics (less than 60 minutes before making the skin incision and discontinuance within 24 hours of surgery) has reduced the incidence to some extent. Tight control of blood sugar and avoidance of hypothermia intraoperatively and administration of a high fraction of inspired oxygen (F io 2 ) in the recovery ward immediately after surgery may also help reduce the risk of SSI, but the value of these measures remains controversial. SSI typically develops 5 to 10 days after surgery and is rarely obvious before the patient goes home, typically on postoperative day 3 to 5. Patients often present a few days after discharge with redness or induration in part of the incision, associated with systemic signs of fever, tachycardia, and worsening gastrointestinal (GI) function. In contrast, laparoscopic incisions are rarely complicated by infection. However, when a circular stapler is used to fashion the gastrojejunal (GJ) anastomosis, the surgeon must enlarge one of the trocar sites to permit introduction of the stapling cartridge, and after the cartridge is fired, it may be difficult to avoid contaminating the wound edge as it is removed from the abdomen. Infection of that particular port site occasionally occurs in that situation.

Early GI Dysfunction

The narrow gastric pouch after RYGB or sleeve gastrectomy is restrictive at the beginning, and patients can usually tolerate only clear liquids in small quantities at first. Patients are usually given written instructions to guide the gradual increase in the quantity and range of foods they can tolerate. Patients who do not receive or who do not understand such instruction have a high incidence of vomiting postoperatively. Many patients will experience a few episodes of vomiting if they relax the vigilance with which they increase their dietary intake, and some vomiting is probably inevitable as they learn how to cope with a sensation of fullness, which is a novel experience for most bariatric patients. However, in well-instructed and supported patients, it should be rare. Rather than berate the patient for failure of compliance, or attribute vomiting to persistence of a psychological compulsion to eat large quantities quickly, the physician should consider organic causes, namely a stricture. Some degree of stricturing of the GJ anastomosis is common, and usually resolves with time (less than 3 months) and can be managed by going back to softer or liquid foods. A more severe stricture may be because of an ulcer at the anastomosis, and the physician should inquire about consumption of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or large pills or resumption of smoking. Endoscopy typically reveals an ulcer with visible suture material or staples ( Fig. 1 ). Such strictures are easy to dilate, and 1 or 2 dilations generally are sufficient.