Until recently, the epidemiology of gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms had not been adequately studied in relation to increasing body mass index. To date there are only a few studies in the literature, and thus the relationship between obesity and specific GI symptoms is poorly understood. Future studies that incorporate different ethnicities from varied geographic locations are urgently required. A greater understanding of how GI symptoms are related to obesity and the physiology will be important in the clinical management of these patients.

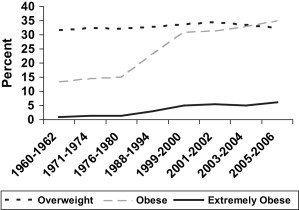

The obesity epidemic has brought with it a barrage of comorbid conditions, medical and psychological complications, and complex patients for the physician to interpret. Studies on the role of gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms in overweight and obese individuals have been very limited, which is surprising given that the GI tract is responsible for the mechanical and chemical breakdown of food for absorption by the body. The prevalence of those classified as overweight in the United States has not changed much since the 1960s, however, there has been a significant almost threefold increase in the prevalence of obesity that started in 1976 to 1980 and peaked in 1999 to 2000. The largest increase has occurred in the extremely obese category; there has been a sevenfold increase in prevalence in this category between 1960 and 2006 ( Fig. 1 ). In the middle of this epidemic of increasing body mass index (BMI, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters) in the United States, the first study assessing the epidemiology of digestive symptoms was conducted at the Johns Hopkins Weight Management Center in 1994. The study aimed to determine the prevalence of GI symptoms among obese and normal weight binge eaters.

It was almost a decade later when a patient-based study of morbidly obese patients undergoing laproscopic Roux-en Y gastric bypass reported substantial increases in GI symptoms compared with normal controls. Following this initial report, there were 3 population-based studies from the United States, New Zealand, and Australia that provided new information about the prevalence of GI symptoms among various BMI categories (normal 18.5–24.9 kg/m 2 , overweight 25.0–29.9 kg/m 2 , obese class I 30.0–34.9 kg/m 2 , obese class II 35.0–39.9 kg/m 2 , and obese class III >40.0 kg/m 2 ). Subsequently, there have been an 5 more studies including 2 from Europe, 2 from the United States, and a recent study from Iran. Moreover, there have been other studies that have provided limited information because of the groups assessed or the variables selected in these studies. Despite the global prevalence of obesity, it is evident from the literature that there are few studies assessing the epidemiology of GI symptoms among overweight, obese, or extremely obese individuals either in the community or among patients in the clinical setting.

This review focus only on studies that have aimed to determine the prevalence of multiple GI symptoms in either patient-based samples or in the community ( Table 1 ).

| Study | Year | Country | Total (n) | Weight Classification | Study Design | Study Sample | GI Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foster et al | 2003 | United States | 43 | BMI | Cross-sectional | Patient | Abdominal pain, GERD, IBS, reflux, dysphagia |

| Delgado-Aros et al | 2004 | United States | 1963 | BMI | Cross-sectional | Population | Nausea, vomiting, satiety, upper abdominal pain, lower abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhea, constipation |

| Talley et al | 2004 | New Zealand | 980 | BMI | Cohort | Population | Abdominal pain, bloating, heartburn, acid regurgitation, diarrhea, constipation, IBS |

| Talley et al | 2004 | Australia | 777 | Increased BMI | Cross-sectional | Population | Nausea, vomiting, early satiety, upper abdominal pain, lower abdominal pain, bloating, postprandial fullness, hard stools, decreased stools, increased stools, loose watery stools, heartburn, acid regurgitation |

| Aro et al | 2005 | Sweden | 983 | BMI | Cross-sectional | Population | Dysphagia, fullness, retching, acid regurgitation, early satiety, nausea, vomiting, heartburn, central chest pain, burning feeling rising in chest, constipation, diarrhea, incomplete evacuation, pain at defecation, pain relieved at defecation, straining, urgency, flatus, abdominal distention, nightly urge to defecate |

| van Oijen et al | 2006 | Netherlands | 1023 | BMI | Cross-sectional | Patient | Acid regurgitation, heartburn, dyspepsia, GERD, lower abdominal pain |

| Cremonini et al | 2006 | United States | 637 | Weight loss/gain | Cohort | Population | Dyspepsia, GERD, chest pain, dyspepsia dysmotility, dyspepsia pain |

| Cremonini et al | 2009 | United States | 4096 | BMI | Cross-sectional | Population | Abdominal pain, fullness, food staying in stomach, bloating, acid regurgitation, heartburn, nausea, vomiting, dysphagia, anal blockage, diarrhea, constipation, lumpy/hard stools, loose/watery stools, fecal urgency, fecal incontinence |

| Pourhoseingholi et al | 2009 | Iran | 2790 | BMI | Cross-sectional | Population | Abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea, bloating, heartburn, anal pain, anal bleeding, nausea and vomiting, dysphagia, incontinence |

Gastrointestinal symptoms

The studies published so far have assessed 47 GI symptoms ( Box 1 ). These consist of upper and lower GI symptoms. The most common symptom assessed in these studies was abdominal pain with 7 out of 9 studies reporting an overall abdominal pain; only 2 studies reported upper and lower abdominal pain as separate symptoms. Upper GI symptoms included acid regurgitation, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), dysphagia, vomiting, heartburn, dyspepsia, retching, and nausea; lower GI symptoms included constipation, diarrhea, fecal incontinence, incomplete evacuation, and anal blockage. Some symptoms were commonly reported in 4 or more studies and these included acid regurgitation, bloating, constipation, diarrhea, dysphagia, heartburn, nausea, and vomiting. Although irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a syndrome and not a categoric symptom, this was included because the data were available from the studies.

- •

Abdominal distention

- •

Abdominal pain

- •

Abdominal pain, upper

- •

Abdominal pain, lower

- •

Acid regurgitation

- •

Anal blockage

- •

Anal pain

- •

Anal bleeding

- •

Bloating

- •

Burning feeling rising in chest

- •

Central chest pain

- •

Chest pain

- •

Constipation

- •

Decreased stools

- •

Diarrhea

- •

Dysmotility

- •

Dyspepsia

- •

Dyspepsia dymotility

- •

Dyspepsia pain

- •

Dysphagia

- •

Early satiety

- •

Epigastric pain

- •

Fecal incontinence

- •

Fecal urgency

- •

Flatus

- •

Food staying in stomach

- •

Frequent stools

- •

Fullness

- •

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- •

Hard stools

- •

Heartburn

- •

Incomplete evacuation

- •

Increased stools

- •

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

- •

Loose/watery stools

- •

Lumpy/hard stools

- •

Nausea

- •

Nightly urge to defecate

- •

Pain at defecation

- •

Pain relieved at defecation

- •

Postprandial fullness

- •

Reflux

- •

Retching

- •

Satiety

- •

Straining

- •

Urgency

- •

Vomiting

Studies evaluating GI symptoms and obesity

Crowell and Colleagues 1994

The aim of this patient-based study was to compare GI symptoms in obese and nonobese binge eaters as defined by DSM-IV. This study was conducted in the United States. There were 119 obese and 77 normal weight women who completed a validated self-report Bowel Symptom Questionnaire (BSQ) and reported GI symptoms in the previous 3-month period. The obese (clinic) patients were significantly younger than the normal weight (community) subjects (45.9 vs 52.0 years, P <.01). Multiple GI symptoms were reported more frequently among the obese binge eaters than the normal weight controls ( P <.001). The prevalence of certain GI symptoms was statistically significant (all P <.05) when comparing obese and nonobese groups: flatus (58% vs 39%), constipation (42% vs 23%), diarrhea (35% vs 19%), straining (32% vs 16%), respectively. These were the only symptoms for which prevalence estimates between obese and nonobese groups were reported in this study.

Foster and Colleagues 2003

This patient-based study from the United States compared the prevalence of GI symptoms among 43 (40 female, 3 male) morbidly obese patients with 36 (23 female, 13 male) normal weight controls. The severely obese patients were all undergoing a laparoscopic Roux-en Y gastric bypass procedure and the normal weight controls were selected at random, although it does not say how these subjects were recruited. Nineteen GI symptoms were grouped into symptom clusters (abdominal pain, GERD, IBS, reflux, and dysphagia) and assessed using a validated questionnaire. The severely obese patients had an average BMI of 47.8 ± 4.9 kg/m 2 ; no average BMI is given for the normal weight control group. The mean age of the severely obese patients was 37.3 ± 8.6 years, and the normal weight subjects were 39.8 ± 11.2 years. The severely obese patients reported a significantly higher prevalence of abdominal pain ( P <.001), GERD ( P <.001), IBS ( P = .02), and reflux ( P <.001) compared with normal weight subjects. However, there was no difference in the rates of dysphagia between the 2 groups.

Delgado-Aros and Colleagues 2004

This was the first population-based study to assess GI symptoms among obese individuals. This study from the United States consisted of 1963 subjects from 2660 (74% response rate) who were randomly selected to receive 2 validated questionnaires (GastroEsophageal Reflux Questionnaire [GERQ] and the Bowel Disease Questionnaire [BDQ]). The classifications of BMI included underweight, normal weight, overweight, obese class I, obese class II, and obese class III. The sample consisted of 51% women and 57% more than 50 years old. The study reported an overall increase in GI symptoms in obese individuals compared with those with normal BMI. The study found a positive relationship between BMI and frequent vomiting ( P = .02), upper abdominal pain ( P = .03), bloating ( P = .002), and diarrhea ( P = .01). Moreover, there was an increased prevalence of frequent lower abdominal pain, nausea, and constipation among obese individuals compared with normal weight subjects, but this was not statistically significant.

Talley and Colleagues 2004a

This study was conducted on a birth cohort from New Zealand aged 26 years and aimed to evaluate the association between BMI and specific GI symptoms. The sample consisted of 980 individuals (94% of the original cohort), with 52.1% male. The sample completed a validated BDQ. The classifications of BMI included normal weight, overweight, and obese (BMI >30 kg/m 2 ). There was a significant correlation between prevalence of diarrhea and increasing BMI. There was no significant correlation evident for increased BMI and the prevalence of reported abdominal pain, bloating, heartburn, acid regurgitation, constipation, or IBS.

Talley and Colleagues 2004b

This population-based study conducted in Sydney, Australia, consisted of 777 adult subjects randomly selected from the community. The study evaluated the association between BMI and specific GI symptoms. The sample selected was 60% female. The mean age was not reported. Subjects completed a validated BSQ. The classifications of BMI included underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese (BMI >30 kg/m 2 ). Prevalence increased significantly with BMI for the following GI symptoms: increased stools ( P <.001), loose watery stools ( P = .02), heartburn ( P <.001), acid regurgitation ( P = .001). In addition, there were significant inverse relationships associated with early satiety ( P = .03).

Aro and Colleagues 2005

The setting for this study was northern Sweden (Kalix and Haparanda) in a community-based endoscopic study of 1001 adults. This study aimed to determine whether obese subjects experience more gastroesophageal reflux symptoms than normal weight subjects. Individuals were asked to complete the validated Abdominal Symptom Questionnaire (ASQ), which assessed 27 troublesome GI symptoms, and underwent an upper endoscopy. BMI was calculated at the endoscopy visit. Fifty-one percent of the subjects were women with a mean age of 53.5 years. The classifications of BMI included normal weight, overweight, and obese (BMI >30 kg/m 2 ). Increasing BMI was associated with dysphagia, retching, acid regurgitation, vomiting, heartburn, central chest pain, burning feeling rising in chest, diarrhea, alternating constipation/diarrhea, incomplete rectal evacuation, urgency, and flatus.

Levy and Colleagues 2005

This study assessed GI symptoms among a group of obese individuals in a weight-loss program. The study was conducted in the United States and included 983 participants (70% women) who had a mean age of 52.7 years. There was no other BMI category (control group) in this study. The BMI was assessed as a continuous variable. No comparisons could be made using the data from this study because the participants were involved in a weight-loss program as part of the study design.

Van Oijen and Colleagues 2006

This patient-based study from the Netherlands recruited 1023 consecutive adult patients who presented for endoscopic assessment of symptoms. This study aimed to assess the relationship between BMI and GI disorders among patients referred for endoscopy. Patients were sent the validated Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS), which asks questions about 8 symptoms. The classifications of BMI included underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese (BMI >30 kg/m 2 ). None of the GI symptoms showed a statistically significant association for increasing prevalence and increasing BMI. Most symptoms were consistently equal across the BMI groups, specifically for GERD, regurgitation, dyspepsia, lower abdominal pain, and heartburn. The lack of correlation between BMI groups conceivably may be caused by selection bias of a patient-population sample that was more likely to have GI symptoms, no matter what the BMI category.

Cremonini and Colleagues 2006

This prospective cohort from Olmstead County in Minnesota in the United States consisted of 637 individuals after a 10-year follow-up period. This study assessed the relationship between changes in body weight and changes in upper GI symptoms. All subjects completed the BDQ, which assessed 46 GI symptoms. The classifications of BMI included underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese (BMI >30 kg/m 2 ); weight change as either gain or loss during the follow-up period was determined. The study group was 53% female, mean age 62 years. Notably, an increase of 4.53 kg (10 lb) between the baseline survey and the 10-year follow-up survey was associated with new onset dyspepsia dysmotility ( P <.01).

Cremonini and Colleagues 2009

This large population-based study included 4096 adults from the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) in Minnesota in the United States. This study aimed to assess overeating and binge eating among various categories of BMI (underweight/normal weight and overweight/obese). All subjects completed the BDQ, which assessed 16 GI symptoms. The classifications of BMI included underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese (BMI >30 kg/m 2 ). The mean age was 51 years; the gender of the population was not reported. Unfortunately, the data in this study did not allow for assessment of prevalence data and increasing BMI as these data were only reported for those classified as “no binge eating,” “binge eating,” or “binge eating disorder.”

Pourhoseingholi and Colleagues 2009

A large cross-sectional household survey was conducted by interview in Tehran, Iran. The aim of this study was to determine the relationship between BMI and functional constipation. A total of 18,180 adults were randomly sampled based on a list from the central post office. A total of 2790 individuals had at least 1 GI symptom and were included in the analysis. The classifications of BMI included normal weight, overweight, and obese (BMI >30 kg/m 2 ). The questionnaire consisted of 2 sections: a section asking about GI symptoms and questions based on the Rome III criteria for functional GI disorders. There were no data on age or gender for this sample; however, for a subsample of 459 individuals who were assessed for functional constipation, the mean age was 47 years and the sample consisted of 70% women. Significant trends in prevalence of GI symptoms associated with increasing BMI included bloating ( P <.001), incontinence ( P = .02), heartburn ( P = .04), nausea, and vomiting ( P = .01). There were no associations with constipation, diarrhea, anal pain, anal bleeding, or dysphagia.

Extreme Obesity

Currently, only 2 studies have assessed GI symptoms among those classified as either obese class II (BMI 35.0–39.9 kg/m 2 ) or extremely obese (BMI >40 kg/m 2 ). Collectively, the studies suggest that those individuals in these groups are much more likely to suffer from certain symptoms. One study contained class II and class III BMI categories and prevalent symptoms included upper abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhea, and satiety, however, this study only assessed 8 symptoms abdominal pain (upper), abdominal pain (lower), bloating, constipation, diarrhea, nausea, satiety, vomiting and therefore the symptom evaluation is limited compared with other studies.

Studies evaluating GI symptoms and obesity

Crowell and Colleagues 1994

The aim of this patient-based study was to compare GI symptoms in obese and nonobese binge eaters as defined by DSM-IV. This study was conducted in the United States. There were 119 obese and 77 normal weight women who completed a validated self-report Bowel Symptom Questionnaire (BSQ) and reported GI symptoms in the previous 3-month period. The obese (clinic) patients were significantly younger than the normal weight (community) subjects (45.9 vs 52.0 years, P <.01). Multiple GI symptoms were reported more frequently among the obese binge eaters than the normal weight controls ( P <.001). The prevalence of certain GI symptoms was statistically significant (all P <.05) when comparing obese and nonobese groups: flatus (58% vs 39%), constipation (42% vs 23%), diarrhea (35% vs 19%), straining (32% vs 16%), respectively. These were the only symptoms for which prevalence estimates between obese and nonobese groups were reported in this study.

Foster and Colleagues 2003

This patient-based study from the United States compared the prevalence of GI symptoms among 43 (40 female, 3 male) morbidly obese patients with 36 (23 female, 13 male) normal weight controls. The severely obese patients were all undergoing a laparoscopic Roux-en Y gastric bypass procedure and the normal weight controls were selected at random, although it does not say how these subjects were recruited. Nineteen GI symptoms were grouped into symptom clusters (abdominal pain, GERD, IBS, reflux, and dysphagia) and assessed using a validated questionnaire. The severely obese patients had an average BMI of 47.8 ± 4.9 kg/m 2 ; no average BMI is given for the normal weight control group. The mean age of the severely obese patients was 37.3 ± 8.6 years, and the normal weight subjects were 39.8 ± 11.2 years. The severely obese patients reported a significantly higher prevalence of abdominal pain ( P <.001), GERD ( P <.001), IBS ( P = .02), and reflux ( P <.001) compared with normal weight subjects. However, there was no difference in the rates of dysphagia between the 2 groups.

Delgado-Aros and Colleagues 2004

This was the first population-based study to assess GI symptoms among obese individuals. This study from the United States consisted of 1963 subjects from 2660 (74% response rate) who were randomly selected to receive 2 validated questionnaires (GastroEsophageal Reflux Questionnaire [GERQ] and the Bowel Disease Questionnaire [BDQ]). The classifications of BMI included underweight, normal weight, overweight, obese class I, obese class II, and obese class III. The sample consisted of 51% women and 57% more than 50 years old. The study reported an overall increase in GI symptoms in obese individuals compared with those with normal BMI. The study found a positive relationship between BMI and frequent vomiting ( P = .02), upper abdominal pain ( P = .03), bloating ( P = .002), and diarrhea ( P = .01). Moreover, there was an increased prevalence of frequent lower abdominal pain, nausea, and constipation among obese individuals compared with normal weight subjects, but this was not statistically significant.

Talley and Colleagues 2004a

This study was conducted on a birth cohort from New Zealand aged 26 years and aimed to evaluate the association between BMI and specific GI symptoms. The sample consisted of 980 individuals (94% of the original cohort), with 52.1% male. The sample completed a validated BDQ. The classifications of BMI included normal weight, overweight, and obese (BMI >30 kg/m 2 ). There was a significant correlation between prevalence of diarrhea and increasing BMI. There was no significant correlation evident for increased BMI and the prevalence of reported abdominal pain, bloating, heartburn, acid regurgitation, constipation, or IBS.

Talley and Colleagues 2004b

This population-based study conducted in Sydney, Australia, consisted of 777 adult subjects randomly selected from the community. The study evaluated the association between BMI and specific GI symptoms. The sample selected was 60% female. The mean age was not reported. Subjects completed a validated BSQ. The classifications of BMI included underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese (BMI >30 kg/m 2 ). Prevalence increased significantly with BMI for the following GI symptoms: increased stools ( P <.001), loose watery stools ( P = .02), heartburn ( P <.001), acid regurgitation ( P = .001). In addition, there were significant inverse relationships associated with early satiety ( P = .03).

Aro and Colleagues 2005

The setting for this study was northern Sweden (Kalix and Haparanda) in a community-based endoscopic study of 1001 adults. This study aimed to determine whether obese subjects experience more gastroesophageal reflux symptoms than normal weight subjects. Individuals were asked to complete the validated Abdominal Symptom Questionnaire (ASQ), which assessed 27 troublesome GI symptoms, and underwent an upper endoscopy. BMI was calculated at the endoscopy visit. Fifty-one percent of the subjects were women with a mean age of 53.5 years. The classifications of BMI included normal weight, overweight, and obese (BMI >30 kg/m 2 ). Increasing BMI was associated with dysphagia, retching, acid regurgitation, vomiting, heartburn, central chest pain, burning feeling rising in chest, diarrhea, alternating constipation/diarrhea, incomplete rectal evacuation, urgency, and flatus.

Levy and Colleagues 2005

This study assessed GI symptoms among a group of obese individuals in a weight-loss program. The study was conducted in the United States and included 983 participants (70% women) who had a mean age of 52.7 years. There was no other BMI category (control group) in this study. The BMI was assessed as a continuous variable. No comparisons could be made using the data from this study because the participants were involved in a weight-loss program as part of the study design.

Van Oijen and Colleagues 2006

This patient-based study from the Netherlands recruited 1023 consecutive adult patients who presented for endoscopic assessment of symptoms. This study aimed to assess the relationship between BMI and GI disorders among patients referred for endoscopy. Patients were sent the validated Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS), which asks questions about 8 symptoms. The classifications of BMI included underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese (BMI >30 kg/m 2 ). None of the GI symptoms showed a statistically significant association for increasing prevalence and increasing BMI. Most symptoms were consistently equal across the BMI groups, specifically for GERD, regurgitation, dyspepsia, lower abdominal pain, and heartburn. The lack of correlation between BMI groups conceivably may be caused by selection bias of a patient-population sample that was more likely to have GI symptoms, no matter what the BMI category.

Cremonini and Colleagues 2006

This prospective cohort from Olmstead County in Minnesota in the United States consisted of 637 individuals after a 10-year follow-up period. This study assessed the relationship between changes in body weight and changes in upper GI symptoms. All subjects completed the BDQ, which assessed 46 GI symptoms. The classifications of BMI included underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese (BMI >30 kg/m 2 ); weight change as either gain or loss during the follow-up period was determined. The study group was 53% female, mean age 62 years. Notably, an increase of 4.53 kg (10 lb) between the baseline survey and the 10-year follow-up survey was associated with new onset dyspepsia dysmotility ( P <.01).

Cremonini and Colleagues 2009

This large population-based study included 4096 adults from the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) in Minnesota in the United States. This study aimed to assess overeating and binge eating among various categories of BMI (underweight/normal weight and overweight/obese). All subjects completed the BDQ, which assessed 16 GI symptoms. The classifications of BMI included underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese (BMI >30 kg/m 2 ). The mean age was 51 years; the gender of the population was not reported. Unfortunately, the data in this study did not allow for assessment of prevalence data and increasing BMI as these data were only reported for those classified as “no binge eating,” “binge eating,” or “binge eating disorder.”

Pourhoseingholi and Colleagues 2009

A large cross-sectional household survey was conducted by interview in Tehran, Iran. The aim of this study was to determine the relationship between BMI and functional constipation. A total of 18,180 adults were randomly sampled based on a list from the central post office. A total of 2790 individuals had at least 1 GI symptom and were included in the analysis. The classifications of BMI included normal weight, overweight, and obese (BMI >30 kg/m 2 ). The questionnaire consisted of 2 sections: a section asking about GI symptoms and questions based on the Rome III criteria for functional GI disorders. There were no data on age or gender for this sample; however, for a subsample of 459 individuals who were assessed for functional constipation, the mean age was 47 years and the sample consisted of 70% women. Significant trends in prevalence of GI symptoms associated with increasing BMI included bloating ( P <.001), incontinence ( P = .02), heartburn ( P = .04), nausea, and vomiting ( P = .01). There were no associations with constipation, diarrhea, anal pain, anal bleeding, or dysphagia.

Extreme Obesity

Currently, only 2 studies have assessed GI symptoms among those classified as either obese class II (BMI 35.0–39.9 kg/m 2 ) or extremely obese (BMI >40 kg/m 2 ). Collectively, the studies suggest that those individuals in these groups are much more likely to suffer from certain symptoms. One study contained class II and class III BMI categories and prevalent symptoms included upper abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhea, and satiety, however, this study only assessed 8 symptoms abdominal pain (upper), abdominal pain (lower), bloating, constipation, diarrhea, nausea, satiety, vomiting and therefore the symptom evaluation is limited compared with other studies.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree