Tara Lee Frenkl, MD, MPH, Jeannette M. Potts, MD People at high risk of contracting STIs are young adults between the ages of 18 and 28. It is also important to bear in mind that STIs rank among the top five risks of international travelers, along with diarrhea, hepatitis, and motor vehicle accidents (Mawhorter, 1997). A urologist should have a high index of suspicion for underlying STI in women who present with recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs) and in those who are symptomatic with sterile urine cultures. Up to 50% of women with signs of UTI during emergency department examination had subsequent positive cultures for STI (Berg et al, 1996). Physicians should maintain the same level of vigilance when treating women who have sex with women. Genital human papillomavirus (HPV) has been identified along with squamous intraepithelial lesions among lesbians and occurs among those who have not had sexual relations with men (Marrazzo et al, 1998). Proctitis may occur in women and men who have anal sex. Causative organisms include Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, Treponema pallidum, and herpes simplex virus (HSV). A discussion of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is beyond the scope of this chapter (see Chapter 14); however, it is important to remember that STIs—especially the ulcerative types—facilitate the transmission and infection of HIV. HSV type 2, in particular, may play a role in the transmission of HIV because it has been identified more frequently than other STIs among HIV-concordant couples. Increased risk of HIV concordance has also been observed among couples who both have Mycoplasma genitalium antibodies (Perez et al, 1998). Evidence is available that has shown that the spermicide nonoxynol-9 is not preventive against STIs and that its frequent use may actually be detrimental by increasing the rate of genital ulceration and HIV transmission (Richardson, 2002). It is estimated that more than 19 million new cases of STIs are reported each year and more than 65 million people are infected with incurable viral STIs (CDC, 2010b; American Social Health Association, 1998). Approximately two thirds of cases occur in adolescents and young adults. The most common STIs are HPV and HSV infections. Of the top 10 nationally notifiable infectious diseases in the United States in 2008, 4 were STIs (CDC, 2008). This does not include HPV and HSV infections because they are not reportable diseases. The prevalence of infection with HPV in the United States is approximately 20 million, and the incidence is 6.2 million (Catea, 1999; Weinstock, 2004). At least 50% of sexually active men and women acquire genital HPV infection at some point in their lives. By age 50, at least 80% of women will have acquired genital HPV infection (STD Facts, 2005). In 2009, only 28 cases of chancroid were reported, down from 67 cases in 2002 (CDC, 2010b). Interestingly, 71% were reported from the three states of Tennessee, Wisconsin, and Texas. Overall, the rate of reported cases has declined 99% since 1987. Haemophilus ducreyi is difficult to culture, and therefore the infection could be underdiagnosed. Improved diagnostic testing by means of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing is now commercially available and may increase diagnostic capability. The incidence of infection with Chlamydia has continued to rise since it became a notifiable disease in 1995. In 2009, over 1.2 million cases were reported to the CDC (CDC, 2010b). The reported number of cases of chlamydial infection was about four times greater than the reported cases of gonorrhea. It is probable that this incidence is at least in part secondary to improved diagnostic ability and growth and implementation of routine screening programs in women. Now that highly sensitive nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) for urine are available, the diagnosis of chlamydial infection is increasing in both symptomatic and asymptomatic men. From 2005 to 2009, the rate of chlamydial infection among men increased 37.6% compared with 20.3% among women. The rate of gonorrhea was fairly stable from 1996-2006 at approximately 115 cases per 100,000 population, and then decreased from 2006-2009 to a rate of approximately 99.1 per 100,000 population in 2009 (CDC, 2009). The incidence rate is highest in persons aged 15 to 24 and is particularly high for non-Hispanic blacks (20 times higher than for non-Hispanic whites). Rates are particularly higher for non-Hispanic blacks (which is 20 times the rate for non-Hispanic whites) and for men who have sex with men (Fox et al, 2001; CDC, 2010b). There has also been a significant increase in quinolone-resistant N. gonorrhoeae, such that fluoroquinolones are no longer recommended for treatment in the United States (CDC, 2007). The rate of syphilis increased yearly during 2001-2009, primarily among men (3.0 cases per 100,000 population in 2001 compared to 7.8 cases in 2009). The rate among women increased from 0.8 cases in 2004 to 1.4 cases in 2009 (CDC, 2010b). It has been proposed that this is secondary to outbreaks among males having sex with males in urban areas with high rates of coinfection with HIV and high-risk sexual behavior (CDC, 2004b). Rates continue to be particularly high in southern states and among African-Americans. There is no evidence that screening high-risk individuals, including those with HIV or other STIs, or the general population reduces morbidity or mortality from syphilis. However, it has been shown that screening pregnant women reduces the prevalence of congenital syphilis (Coles et al, 1998). In the past, once an STI was reported to the health department the health department notified past and present sexual partners of the patient. However, the increased incidence of HIV and threats of bioterrorism are competing for health department resources and many departments now only notify partners of patients with HIV or syphilis (Erbelding and Zenilman, 2005). Patients are now requested to notify their own partners, who are then expected to go for evaluation and treatment themselves. The problems with this proposal are evident, and already this concept has been shown to be ineffective (Macke and Maher, 1999). Golden and colleagues (2003) reported their success implementing an expedited treatment plan for partners that did not require medical evaluation. This was a randomized controlled trial in which patients in the expedited treatment group were given a “partner packet” of therapy to deliver to the partner themselves or, if they were unwilling to do so, the partner was notified by the physician staff and the packet was delivered by mail or could be picked up at a participating pharmacy. Both the patients and partners in the expedited treatment group had better outcomes than the control group. Although this approach is sensible, effective, and progressive, legal and clinical barriers may unfortunately prevent the widespread acceptance of this approach. In 2006 the CDC concluded that EPT has been shown to be at least equivalent to patient referral in preventing persistent or recurrent gonococcal or chlamydial infection in heterosexuals and released guidelines for the uses of EPT (CDC, 2006). The guidelines recommend that EPT should be implemented only when other management strategies are impractical or unsuccessful. All recipients should be encouraged to seek medical attention in addition to accepting therapy by EPT, through counseling of the index case, written materials, and/or personal counseling by a pharmacist or other personnel. However, EPT should not be used routinely in men who have sex with men because of a lack of data to confirm efficacy in this population and the high risk of comorbidity, especially with undiagnosed HIV. Similarly, EPT should not be used for partners of women with trichomoniasis because of the high risk of comorbidity with chlamydial or gonococcal infection or in the management of patients with infectious syphilis. The CDC collaborated with the Center for Law and the Public’s Health at Georgetown and Johns Hopkins Universities to assess the legal framework concerning EPT in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. The objective of the research was to conceptualize and identify legal provisions that implicate a clinician’s ability to execute EPT. As of January 2011, EPT is allowable in 27 states, potentially allowable in 15 states including the district of Columbia and Puerto Rico, and legally prohibited in 8 states. The results of the research, explanation, and up-to-date legal status for each state can be found at the CDC website (CDC, 2010; www.cdc.gov/std/ept/legal). Although specificity for clinical diagnosis of genital ulcer disease is good (94% to 98%), sensitivity is quite low (31% to 35%) (DiCarlo and Martin, 1997). Inguinal lymph node findings did not contribute to diagnostic accuracy. Patients with genital, perianal, or anal ulcers should undergo a diagnostic evaluation for HSV and serologic testing for syphilis. Testing for Haemophilus ducreyi should be conducted in areas where chancroid is prevalent. Specifically, the CDC recommends (1) serology and either darkfield examination or direct immunofluorescence for Treponema pallidum, (2) culture or PCR test for HSV, and (3) serologic testing for type-specific HSV antibody (CDC, 2010c). One should bear in mind that patients may have more than one STI. Approximately 10% of patients with chancroid also have HSV infection or syphilis. HIV testing should also be considered in the management of patients with confirmed STI. Clinical characteristics of sexually transmitted genital ulcers are summarized in Table 13–1. Other causes that are not sexually transmitted, such as Behçet syndrome, drug reaction, erythema multiforme, Crohn disease, lichen planus, amebiasis, trauma, and carcinoma, must also be considered. Empirical treatment for the most likely cause based on history and physical examination should be initiated as laboratory test results are pending. If ulcers do not respond to therapy or appear unusual, a biopsy should be performed. Genital herpes infection is common, afflicting more than 50 million people in the United States (Xu et al, 2006). It is caused by HSV type 2 (HSV-2) in 85% to 90% of cases and HSV type 1 (HSV-1) in 10% to 15% of cases. HSV-1 is responsible for common cold sores but can be transmitted via oral secretions during oral-genital sex. Silent infection is common and may account for more than 75% of viral transmission (Langenberg et al, 1999). Up to 80% of women with HSV-2 antibodies have no history of clinical infection (White and Wardropper, 1997). The incubation period ranges from 1 to 26 days but is usually short, approximately 4 days. Nongenital infection of HSV-1 during childhood may be protective to some extent against subsequent genital HSV-2 infection in adults. When exposed to HSV-2, women with negative HSV-1 antibodies had a 32% risk of infection per year whereas women with positive antibodies had a 10% risk of infection per year (Baker, 1997). Primary infection manifests as painful ulcers of the genitalia or anus and bilateral painful inguinal adenopathy. The initial presentations for HSV-1 and HSV-2 are the same. A group of vesicles on an erythematous base that does not follow a neural distribution is pathognomonic (Figs. 11-1 to 11-3). The differential diagnosis includes other STIs, such as primary syphilis and chancroid, as well as noninfectious disorders such as Crohn disease, trauma, contact dermatitis, erythema multiforme, Reiter syndrome, psoriasis, and lichen planus. The initial infection is often associated with constitutional flulike symptoms. Sacral radiculomyelopathy is a rare manifestation of primary infection that has a greater association with primary anal HSV. Genital lesions, especially urethral lesions, may cause transient urinary retention in women. Recurrent episodes are usually less severe, involving only ulceration of the genital or anal area. Severe disease and complications of herpes include pneumonitis, disseminated infection, hepatitis, meningitis, and encephalitis. Asymptomatic viral shedding can take place for up to 3 months after clinical presentation, thereby perpetuating the risk of transmission (Baker, 1997). The diagnosis of genital herpes should not be made on clinical suspicion alone because the classic presentation of the ulcer occurs in only a small percentage of patients. Women especially may present with atypical lesions such as abrasions, fissures, or itching (ACOG Practice Bulletin, 2004). Viral culture with subtyping has been the gold standard of diagnosis of herpes infection. Viral subtype should be determined in every patient because it is important for prognosis and counseling. Women with HSV-2 have an average of four recurrences within the first year, and women with HSV-1 have one recurrence in the first year. After the first year, HSV-1 rarely recurs whereas the rate of HSV-2 decreases but slowly (Bendedetti et al, 1994). Viral culture can generally isolate the virus in 5 days, is relatively inexpensive, and is highly specific. However, the sensitivity of viral culture ranges from 30% to 95%, depending on the stage of the lesion and whether it is the primary infection or a recurrence. Viral load is highest when the lesion is vesicular and during primary infection. Therefore, viral culture has the highest sensitivity at these times and declines sharply as the lesion heals. There are currently three U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved type-specific antibody assays (HerpeSelect HSV-1 and HSV-2 ELISA, HerpeSelect HSV-1 and HSV-2 Immunoblot, and Captia ELISA). These tests identify antibodies to HSV glycoproteins G-1 and G-2, which evoke a type-specific antibody response (Wald and Ashley-Morrow, 2002). These tests may also be able to identify recently acquired versus established HSV infection based on antibody avidity (Morrow et al, 2004). Antiviral therapies approved for treatment include those using oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir (Table 13–2). Topical antiviral medications are not effective. Recurrences can be treated with an episodic or suppressive approach. When used for episodic treatment, medication must be initiated during the prodrome or within 1 day of the onset of lesions. Daily suppressive therapy has been shown to prevent 80% of recurrences and is an option for patients who suffer from frequent recurrences. It has been shown to decrease the frequency and duration of recurrences as well as viral shedding and therefore reduce the rate of transmission. The safety and efficacy of daily suppressive therapy has been well documented. Chancroid, caused by Haemophilus ducreyi, is the most common ulcerative STI worldwide but is rare in the United States. It affects men three times more often than women. The incubation period ranges from 1 to 21 days. It causes a painful, nonindurated ulcer on the penis or vulvovaginal area. The ulcer has a friable base covered with a gray or yellow purulent exudate and a shaggy border. It can spread laterally by apposition to inner thighs and buttocks, especially in women. It is associated with inguinal adenopathy that is typically unilateral and tender with a tendency to become suppurative and fistulize (Figs. 13-4 and 13-5). H. ducreyi is fastidious and difficult to culture. The special culture media is not widely available, and sensitivity of culture remains less than 80%. Gram stain of a specimen obtained from the undermined edge of the ulcer may be more helpful in identifying the short, fine, gram-negative streptobacilli, which are usually arranged in short, parallel chains. Recently, PCR assays have been shown to be a sensitive and specific means of detecting H. ducreyi. Although no PCR test is currently FDA approved, testing can be performed by commercial agencies. HIV and syphilis screening should be performed at the time of diagnosis and 3 months after treatment if initial results are negative. Single-dose treatments consist of azithromycin, 1 g orally, or ceftriaxone, 250 mg intramuscularly. Alternative regimens include ciprofloxacin, 500 mg twice daily for 3 days, or erythromycin base, 500 mg by mouth three times daily for 7 days. However, antibiotic susceptibility varies geographically. Resistance has been reported to ciprofloxacin and erythromycin in some regions. Ciprofloxacin is contraindicated during pregnancy and lactation. Subjective improvement should be noted within 3 days, and ulcers generally heal completely in 7 to 14 days. Healing may be slower in uncircumcised men with ulcers below the foreskin and in patients with HIV (Schmid, 1999). Patients should be reexamined in 5 to 7 days. Sexual partners should be examined and treated if sexual relations were held within 2 weeks before or during the eruption of the ulcer. Symptomatic relief of inguinal tenderness can be provided by needle aspiration or incision and drainage of the buboes. Syphilis is caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. Incubation periods range between 10 and 90 days. It is spread through contact with infectious lesions or body fluids. It can also be acquired in utero and through blood transfusion. Syphilis has been categorized into overlapping stages based on clinical signs and symptoms to guide diagnosis and treatment. Primary syphilis is characterized by a single painless, indurated ulcer occurring at the site of inoculation that appears about 3 weeks after inoculation and persists for 4 to 6 weeks (Figs. 13-6 and 13-7). The ulcer is typically found on the glans, corona, or perianal area on men and on the labial or anal area on women. It is often associated with bilateral, nontender inguinal or regional lymphadenopathy. Because the ulcer and adenopathy are painless and heal without treatment, primary syphilis often goes unnoticed. Secondary syphilis usually begins 4 to 10 weeks after the appearance of the ulcer but may present as long as 24 months after the initial infection. Secondary syphilis manifests as mucocutaneous, constitutional, and parenchymal signs and symptoms (Figs. 13-8 and 13-9). Frequent early manifestations consist of maculopapular rash, which is commonly seen on the trunk and arms, and generalized nontender lymphadenopathy. After several days or weeks, a papular rash may accompany the primary rash. These papular lesions are associated with endarteritis and may therefore become necrotic and pustular. The distribution widens and commonly affects the palms and soles. In the intertriginous areas these papules may enlarge and erode to produce condyloma lata, which are particularly infectious. Less common manifestations of secondary syphilis include hepatitis and immune complex–induced glomerulonephritis (Goldmeier and Guallar, 2003). Darkfield microscopy and direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) tests can be performed on specimens obtained from primary or secondary lesions. Darkfield microscopy is not widely available, but DFA testing of a fixed smear from a lesion can be performed at many commercial laboratories. Nontreponemal serologic testing with rapid plasma reagin (RPR) or Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) are the most common methods of screening suspected individuals. Sensitivity is 78% and 86% for RPR and VDRL, respectively, in primary syphilis, 100% for both in secondary syphilis, and over 95% in tertiary syphilis (Hart, 1986). The false-positive rate is 1% to 2% and may be secondary to a large variety of causes (Golden et al, 2003). Therefore, all positive tests should be confirmed with treponemal testing using T. pallidum particle agglutination (TP-PA) or fluorescent treponemal antibody absorbed (FTA-ABS) testing. HIV can cause false-negative results by both treponemal and nontreponemal methods (Hicks et al, 1987; Erbelding et al, 1997). Positive treponemal antibody tests usually remain positive for life and do not correlate with disease activity. Nontreponemal antibody titers, RPR and VDRL, correlate with disease activity. These tests usually become negative 1 year after treatment. A low percentage of patients remain “serofast,” never regaining a negative titer. A fourfold difference in titer is reflective of a clinically significant difference. A fourfold increase after therapy is indicative of ineffective therapy or reinfection (Johnson and Farnie, 1994). A fourfold decrease represents successful treatment. Following disease activity, the same test, either RPR or VDRL, should be performed at the same laboratory because the results are not interchangeable and may vary from laboratory to laboratory. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that pregnant women and people who are at higher risk for syphilis infection receive screening tests for the disease (Calonge, 2004). People at higher risk for syphilis include men who have sex with men and engage in high-risk sexual behavior, commercial sex workers, persons who exchange sex for drugs, and those in adult correctional facilities. The CDC recommends that HIV testing should be considered in the initial evaluation of all patients with syphilitic infection and that screening for hepatitis B and C, gonorrhea, and chlamydial infection also should be considered. The presence of chancres increases the risk of HIV acquisition twofold to fivefold (Greenblatt et al, 1988; Stamm et al, 1988). For late latent syphilis, latent syphilis of unknown duration, or tertiary syphilis with no evidence of neurosyphilis, benzathine penicillin, 2.4 million units intramuscular injection should be repeated weekly for a total of three doses (total dose of 7.2 million units) or doxycycline therapy extended for a total of 4 weeks. In pregnancy, the alternative regimens of doxycycline and tetracycline should not be used and desensitization to penicillin is recommended if the patient has a penicillin allergy. Small studies have shown that azithromycin or ceftriaxone may be potential alternatives for early syphilis, but insufficient data are available to make definitive recommendations (Augenbraun and Workowski, 1999; Gruber et al, 2000; Hook et al, 2002). Patients should be followed with nontreponemal antibody titers at 6 and 12 month. Patients with HIV should be followed at 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 months. A fourfold decrease in antibody titer is usually reflective of cure. The rate of treatment failure ranges from 4% to 21% (Parkes et al, 2004

Epidemiology and Trends

Expedited Partner Therapy

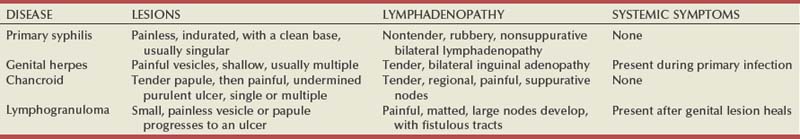

Genital Ulcers

Herpes Simplex Virus Infection

Diagnosis

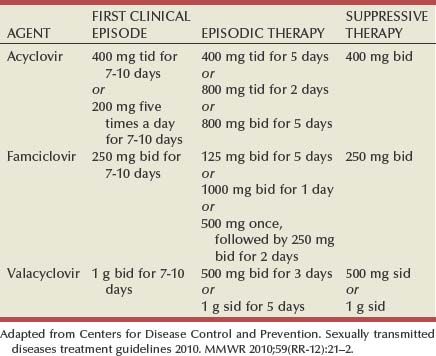

Treatment

Chancroid

Diagnosis

Treatment

Syphilis

Diagnosis

Treatment

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree