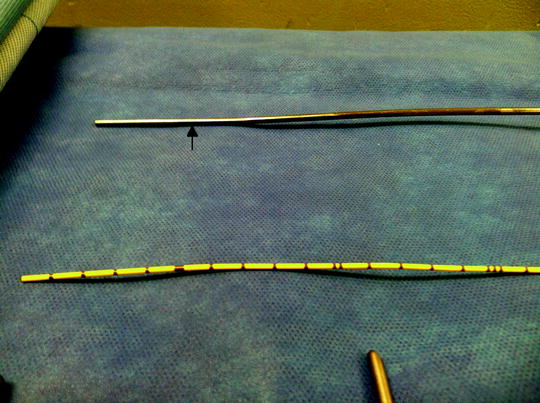

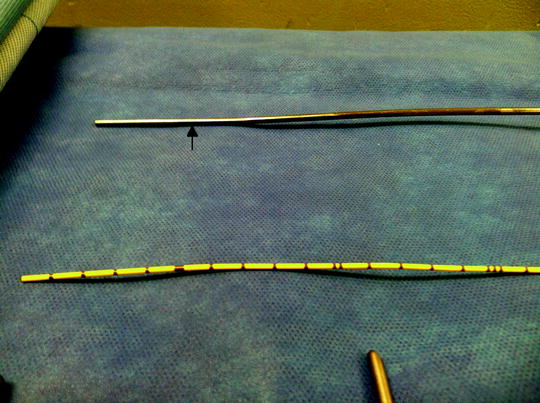

Fig. 23.1

Basic semirigid ureteroscopy (arrow) setup

The essential paraphernalia, such as stone baskets and ureteral stents, needed for rigid and semirigid ureteroscopy is listed elsewhere in this book.

Techniques for Passage of Semirigid Ureteroscope: A Step-by-Step Approach

As mentioned in the previous chapter on rigid ureteroscopy, one must be cognizant of the anatomy of the ureter as it hugs the lateral aspect of the pelvis, crosses over the iliac vessels, and traverses on top of the psoas muscle, finally descending into the renal fossa lateral to the great vessels. Thus, the natural course of the ureter makes several tortuous turns creating several pressure points. This anatomic awareness is crucial in not only navigating up the ureter but also in preventing complications. An informed consent elaborating the benefits, risks, and other treatment options should be discussed and obtained prior to initiating the procedure. Sterile urine is essential prior to ureteroscopy and should also be included in the preoperative evaluation.

The technique required for passing the semirigid ureteroscope is one that, with care, can be easily mastered. It is an extension of an urologist’s cystoscopic skills, though with a different set of indications and potential adverse events. It should be introduced into the ureter with caution, as a semirigid ureteroscope should be treated as a “weapon.” The room set up should be the same as for cystoscopy with the video and fluoroscopic monitors ergonomically placed for the operating surgeon. Normal saline is the preferred irrigation solution and the option of using a pressure bag should be available. Other pressure irrigation devices are commercially available and their use is discussed below.

After confirming the correct side and performing a cystoscopic examination of the bladder, a GW is placed into the ureteral orifice and its position confirmed by fluoroscopy. We recommend that semirigid ureteroscopy be performed along side the stiffest wire possible, such as an Amplatz Super Stiff™ (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA). However, it is best to place a floppy tipped GW, such as a Bentson™ GW (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN) initially and exchange this, if needed, using a ureteral catheter, to prevent ureteral trauma or perforation. There are a variety of GWs from different manufactures that one can utilize.

At this point one has established access to the ureter and kidney, it is imperative that it not be compromised and thus securing this GW, coiled, to the contralateral side by a hemostat to the drape prevents migration of the wire and inadvertent dislodgement. This GW is considered the lifeline of the procedure, especially if there are any adverse events.

The technique for passing the semirigid ureteroscope is similar to that of a rigid ureteroscope, however it should be performed with extreme caution. Depending on the manufacturer and the size, the tip of the ureteroscope is much more pointed than that of the rigid ureteroscope and thus can easily create a false passage in the ureter (Fig. 23.2). It is also incumbent on the operator to maintain the sterility of the scope as its length can easily inadvertently contaminate the surgical field, beyond the sterile area.

Fig. 23.2

Image shows the diameter comparison of the semirigid ureteroscope (arrow) and a 5 Fr ureteral catheter

The passage of the semirigid ureteroscope starts by placing the tip within the urethra. The scope is then advanced into the bladder maintaining the urethral lumen in the center of the visual field. When passing the scope on a male, the sphincter and prostate may act as a fulcrum and the movements to facilitate passage may seem exaggerated when compared to cystoscopy or in females. As long as the urethral lumen is maintained within the center of the field, access to the bladder can be accomplished even with large prostates.

Once inside the bladder, access to the ureter is achieved by locating the GW and placing the scope tip underneath it. This serves to elevate the ureter and open the ureteral orifice. The scope is then advanced carefully, again maintaining the lumen within the field of vision on the video monitor.

Any resistance met during passage, or lack of progress, should be evaluated and consideration given as to the safety to proceed. If one begins to create a false passage, as determined by raising of a flap of mucosa, an alternative method of treatment such as flexible ureteroscopy or introducing a ureteral stent and returning at a later date to obtain passive dilation of the ureter should be considered.

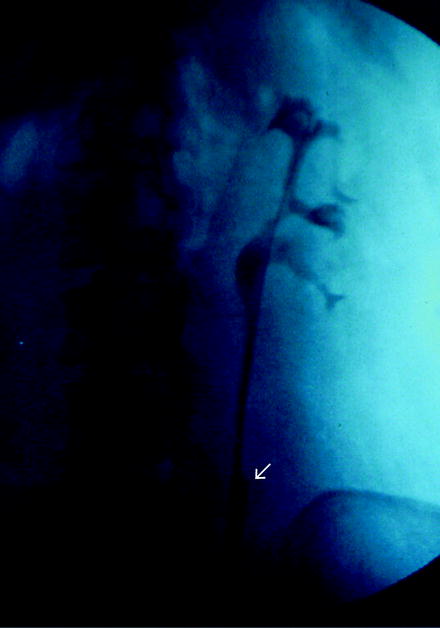

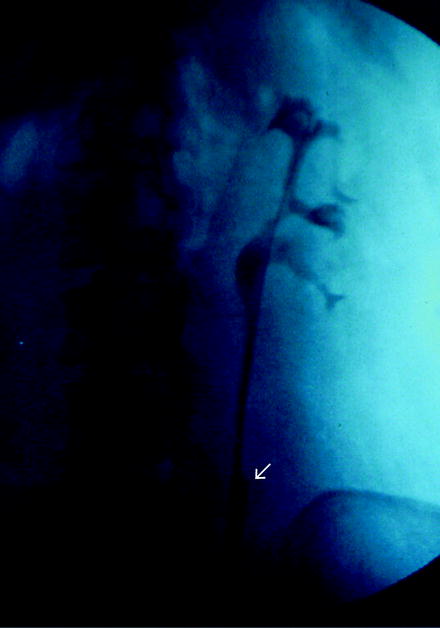

Many authors recommend limiting rigid and semirigid ureteroscopy to diagnose or treat ureteral pathology distal to the iliac vessels. However, with caution one can advance the semirigid ureteroscope into the proximal ureter (Fig. 23.3). Factors such as muscular (large psoas muscles) body habitus, obesity, and prior lower ureteral surgery will make passage of the semirigid ureteroscope challenging, if not impossible. This is when the flexible ureteroscope, as described elsewhere in this book, may become a better treatment option. If either of these issues is encountered, passive dilation by ureteral stent placement may be required. Thus, it is important to preoperatively counsel the patient that future staged treatments may be required. It is also important to caution users, particularly those accustomed to the rigid ureteroscope, that bending the semirigid ureteroscope can be significant without losing visual acuity. Thus, periodic evaluation with fluoroscopy should confirm safe passage.

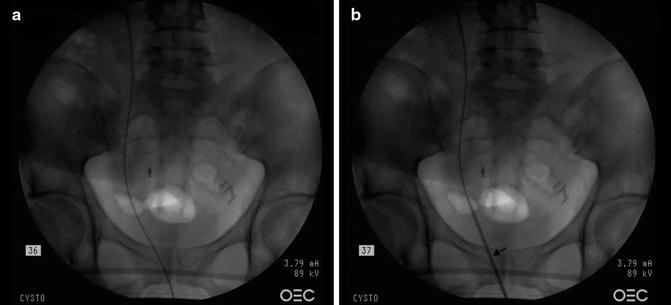

Fig. 23.3

Fluoroscopic image showing the semirigid ureteroscopy proximal to the iliac vessels

If no problems are encountered, the semirigid ureteroscope can be safely passed from the distal ureter into the proximal ureter, and in many patients one can access the renal pelvis and even the upper calyx. When the anticipated area of interest is reached, the pathology is visualized before treatment is initiated or a biopsy taken. This is when ureteral calculi can be basketed or fragmented and basketed. Also, if a ureteral tumor is encountered this can’t only be biopsied but also treated. Unfortunately, all semirigid ureteroscopic procedures do not always proceed as planned. Individual patient variability will introduce challenging scenarios, which will need caution, skill, and experience to overcome. As with any endoscopic procedure, problems will be encountered. Below we have listed common challenges that one will face when performing semirigid ureteroscopy.

Overcoming Problems

Accessing the Ureter

Often one is met with the inability to gain access into the ureteral orifice. If this occurs there are several options left to the surgeon.

In females or children after placing a GW, we have found that passage of a 10 Fr fascial dilator normally used for percutaneous tract dilation, can easily dilate the ureteral orifice allowing for an adequate diameter to accommodate passage of the ureteroscope (Fig. 23.4). This fascial dilator has a tip with adequate flexibility to be safely passed over a GW, under fluoroscopy, but enough rigidity to prevent kinking of the GW.

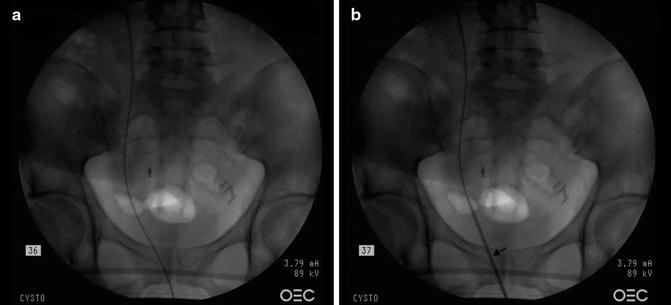

Fig. 23.4

(a) Guide-wire seen in the right ureter. (b) 10 Fr Fascial dilator seen over guide-wire (arrow)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree