Chapter 5 Sedation in ERCP

Defining the Continuum of Sedation

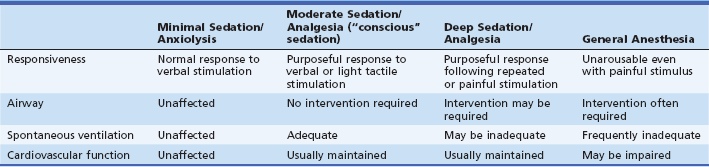

Sedation is typically characterized using the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ (ASA) Continuum of Sedation, which defines four discrete levels of sedation (Table 5.1).1 Depth is most frequently defined by patient responsiveness during the procedure, although the corresponding cardiopulmonary sequelae of this degree of awareness does not directly translate into the probability of sedation-related AEs. In moderate (also known as “conscious”) sedation, patients may be sleeping but will have purposeful response to verbal stimuli, with or without light tactile stimulation. In patients who are deeply sedated, this response occurs only after repeated or painful stimuli. In reality, patients rarely meet only one of these definitions during the course of endoscopy, and these levels actually represent a continuum. The amount of sedation administered to achieve moderate (“conscious”) sedation often inadvertently leads to deep sedation.2 Similarly, patients who are targeted for deep sedation often meet criteria for general anesthesia and are unresponsive to repeated stimulation. This concern has been the cornerstone of the ASA’s lobbying against NAAP.

Table 5.1 ASA Continuum of Sedation

From ASA Task Force on Sedation and Analgesia by Non-Anesthesiologists. Practice guidelines for sedation and analgesia by non-anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:1004-1017.

Many patients undergoing ERCP often require deep sedation since these procedures are typically longer in duration and require less spontaneous patient movement to achieve technical success. In a study in which the depth of sedation was serially assessed during ERCP, 85% of patients met criteria for deep sedation during the course of the procedure.2 Consequently, the ASA recommends that the sedation provider be adequately trained in rescue maneuvers commensurate with one level of sedation higher than the intended sedation target. Therefore patients targeted for deep sedation should be managed by a provider who is trained in the administration of general anesthesia. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has endorsed this recommendation, releasing a clarification letter to its policy on Hospital Anesthesia Services in 2010 after the major gastrointestinal (GI) societies in the United States made a concerted push to endorse NAAP for low-risk patients undergoing routine endoscopy.3,4

The current options for sedation in ERCP can be simplified into two categories: endoscopist-administered or anesthesiologist-administered. Since propofol cannot be administered by nonanesthesiologists in the United States, endoscopist-administered sedation implies moderate sedation using conventional agents (combination of benzodiazepine and opiate). Anesthesiologists may choose between general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation at the onset of the procedure or monitored anesthesia care (MAC). In the latter scenario patients are typically sedated using a propofol-based regimen with a goal of achieving deep sedation. Endoscopists increasingly prefer anesthesia-administered sedation for all endoscopic procedures. The growing role of propofol in endoscopic practice is reflected in epidemiologic data predicting an increase in anesthesia-administered sedation from nearly 25% of routine endoscopies in 2007 to more than 50% in 2015.5 Between 2001 and 2003, Medicare charges for anesthesia during colonoscopy alone increased 86%, to $80,000,000.6 With greater scrutiny on cost effectiveness in health care, judicious use of anesthesia will mandate an improved preprocedure risk assessment; this is particularly important in ERCP, where the potential for sedation-related AEs is higher than with any other endoscopic procedure.

Defining Sedation-Related Adverse Events

Adverse events specifically related to sedation are usually classified in the literature by objective criteria such as oxygen desaturation, aspiration, laryngospasm, apnea, and the need for airway rescue maneuvers or reversal agents. Mortality data related to sedation in endoscopy are sparse, particularly in ERCP. The risk of death is probably close to 0.03% for patients undergoing routine endoscopy using conventional sedation regimens.7 Fewer studies track the frequency of airway rescue maneuvers such as a chin lift, nasal trumpet insertion, and transient positive pressure (also known as bag-mask) ventilation.8 These may be performed as preventive maneuvers in anticipation of hypoxemia or apnea and reflect the importance of having a sedation provider experienced in airway rescue. Endotracheal intubation is rarely necessary in the setting of NAAP during routine endoscopy; rates of endotracheal intubation during administration of MAC during ERCP are less defined, although in a study of 528 ERCP patients undergoing MAC there was a 3% incidence of unplanned endotracheal intubation.9

Safety of Alternative Approaches to Sedation in ERCP

Anesthesiologist-Administered Sedation

While the safety profile of general anesthesia is excellent, with an estimated 1 death per 200,000 to 300,000 cases,10 there are limited data on the safety of anesthesiologist-administered sedation specifically during ERCP.9,11–13 Many anesthesiologists are reluctant to use MAC in ERCP with the patient in the prone position since it is difficult to maintain a patent airway and to monitor respirations. While monitoring chest wall excursions is more difficult in ERCP with the overlying fluoroscopy equipment, the prone position is not an independent predictor of sedation-related AEs and in fact may confer some protection against aspiration versus patients who are supine.8,14 However, there is a perceived risk of aspiration when the patient is supine when not endotracheally intubated. While the left lateral decubitus position may be less of a risk for aspiration than the supine position, radiographic images are often suboptimal. When administered by an experienced provider, MAC has a favorable safety profile for ERCP sedation and for sedation during other advanced endoscopic procedures.8,9

Nonanesthesiologist-Administered (Endoscopist-Administered) Sedation

In most facilities, ASA practice guidelines for sedation administered by nonanesthesiologists are used as the standard for local practices such as preprocedure evaluation and duration of fasting.1 However, these guidelines have not been updated since 2002 despite a multitude of interval studies in which various sedation strategies for endoscopy have been evaluated. Endoscopist-directed sedation in ERCP generally refers to the use of combination benzodiazepines and opiates targeted for moderate sedation. Advantages of this combination include the ability to administer reversal agents in the event of a sedation-related AE, amnestic effect, and sustained analgesia during the postprocedure recovery period (typically several hours). In cases where these agents cannot provide adequate depth or duration of sedation to complete the procedure, antihistamines (e.g., diphenhydramine or promethazine) and droperidol, among others, can be used.15–17 Use of antihistamines increases the likelihood of requiring reversal agents by potentiating the risk of apnea. While still used in some endoscopy units, droperidol has fallen out of favor due to QT interval prolongation and potential for ventricular arrhythmia. That being said, conventional agents are limited by their slower onset of action compared to propofol-based regimens, difficulty in titration during prolonged ERCPs, and limited efficacy. This is compounded by a higher risk of AEs among patients using opiate medications prior to the procedure, which is particularly common in patients undergoing ERCP. This is due to obstructive pathology of the pancreatobiliary tree (e.g., stones, tumors) causing pain at the time of clinical presentation. ERCP technical success rate is significantly higher when patients are sedated using general anesthesia compared to traditional combination regimens as a result of improved sedation.13 Hence there is a growing trend in the use of propofol-based sedation in ERCP.

Ironically, there are more publications studying the safety of NAAP in endoscopy than conventional regimens of combination benzodiazepines and opiates.18–24 Essentially, NAAP is defined as the administration of propofol with or without low doses of opiates and benzodiazepines by a nonanesthesiologist (e.g., a registered nurse under the supervision of the treating endoscopist, or a nonanesthesiologist physician who is not otherwise involved in the endoscopy). NAAP is only cost effective compared to anesthesiologist-administered sedation when a trained, registered nurse can administer the propofol under endoscopist supervision.18 Note that the targeted level of sedation in NAAP administration is moderate.

Initially approved for the induction and maintenance of anesthesia, propofol (2,6-diisopropylphenol) has become an increasingly popular sedative for endoscopic procedures due to its rapid onset of action (30 to 45 seconds) and short duration of effect (4 to 8 minutes).25,26 In the United States, propofol administration is currently restricted to anesthesiologists due to concerns for its relative potency, lack of an antagonist, and potential for rapid change in the depth of sedation from moderate sedation to general anesthesia. Despite these concerns, data from 223,656 published and 422,424 unpublished cases of NAAP in routine endoscopy suggest a favorable safety profile when administered by experienced registered nurses under supervision by endoscopists.22 The safety and efficacy of NAAP for routine endoscopic procedures has been reported in other trials,19,22,27,28 prompting a joint statement by the four largest GI societies in the U.S. advocating the use of NAAP for routine endoscopy in low-risk patient populations.4 In addition, there are several studies supporting NAAP use in advanced endoscopic procedures such as ERCP.18,21,29–34 However, data specifically related to ERCP are limited and no studies have followed a true NAAP protocol. Nevertheless, in a meta-analysis of 12 trials of propofol sedation during routine endoscopy, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), and ERCP, the overall rate of cardiopulmonary AEs was lower than that of standard combination opiate-benzodiazepine regimens.35

There are several unique characteristics of ERCP compared to other endoscopic procedures that may accentuate the benefits of propofol. Specifically, ERCPs tend to be longer in duration and require sustained patient cooperation to achieve technical success.13 Longer procedures require higher cumulative doses of benzodiazepines and opiates to maintain moderate sedation, which translates into longer recovery times. In addition, patients undergoing ERCP with manometry of the biliary and/or pancreatic sphincters are limited to low-dose opiate to minimize the effect on sphincter pressure.36

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree