Renal and Perirenal Abscesses

Neha D. Nanda

Louise M. Dembry

Bacterial infections of the kidney and perinephric space include a spectrum of pathologic conditions that can be divided into intrarenal and perirenal abscesses. Both conditions are suppurative infections localized either within the parenchyma of the kidney (intrarenal abscess, i.e., renal cortical abscess and corticomedullary abscess) or within the perirenal fascia external to the kidney capsule (perinephric abscess), and each can be identified by specific diagnostic techniques. The incidence of intrarenal and perirenal abscesses ranges from one to 10 cases per 10,000 hospital admissions. In the preantibiotic era, most cases were caused by hematogenous seeding from distant foci of infection and were predominantly in young males without an antecedent history of renal disease. Currently, most cases occur as a complication of urinary tract infection and affect males and females with equal frequency. The incidence increases with age and if an abnormality of the genitourinary tract exists. This chapter covers only the more common types of these renal and perirenal infections.

INTRARENAL ABSCESS

Renal Cortical Abscess (Renal Carbuncle)

Etiology

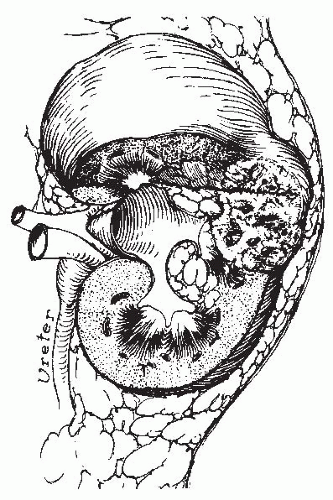

A renal carbuncle (from the Latin, carbunculus, or “little coal”) is a circumscribed, multilocular abscess of the renal parenchyma, which forms from a coalescence of multiple cortical microabscesses (Fig. 24.1). It is most commonly caused by staphylococci (Staphylococcus aureus) and is the result of metastatic spread from a primary focus of infection elsewhere in the body, most commonly the skin. Renal carbuncles were first described by Israel in 1905 in a presentation before the Free Society of Berlin Surgeons.1 Although numerous reports and reviews2,3,4,5,6,7,8 have been published since Israel’s initial description, the total number of reported cases of renal carbuncle remains relatively small.

Pathogenesis

A renal cortical abscess results from a primary focus of infection elsewhere in the body. Common primary foci are cutaneous carbuncle, furunculosis, cellulitis, paronychia, osteomyelitis, endovascular infection, and infection of the respiratory tract. Important predisposing conditions that increase the risk of bacteremia and hematogenous spread are injection drug use, hemodialysis, and diabetes mellitus. S. aureus is the most common causative agent (90%) and infects the cortex of the kidney by hematogenous dissemination from the primary focus, often resulting in several interconnecting furuncles or microabscesses. Coalescence may occur with progression of the infection to a lesion consisting of a fluid-filled mass with a relatively thick wall. Rarely, the process may extend to the periphery of the renal cortex and rupture through the capsule, leading to formation of a perinephric abscess. The majority of renal cortical abscesses are unilateral (97%) single lesions (77%) occurring in the right kidney (63%), and are not associated with perinephric abscesses (90%). The reason for unilateral localization is not clear, although diminished resistance of the kidney resulting from previous disease or injury, including trauma, has been cited as a predisposing factor.9 Infrequently, ascending infection causes a renal cortical abscess.10,11 Because the interval between the original staphylococcal infection and the onset of clinical symptoms of a renal cortical abscess may vary from a few days to many months (average time of approximately 7 weeks),9 the primary focus of infection may have healed and is not apparent in one third of affected patients.5,7

Clinical Features

Renal cortical abscesses are three times more common in males than females. The disease occurs at all ages but is most common between the second and the fourth decades of life.9 The clinical picture of a renal cortical abscess is nonspecific. Most patients have chills, fever, and abdominal or back pain.5,7,9 Some may have a palpable flank mass. Others present with a clinical picture of fever of undetermined origin, with few or no localizing signs.12 Most patients have no urinary symptoms9 because the abscess occupies a circumscribed area within the parenchyma of the kidney, which may not communicate with the excretory passages.

Physical examination often reveals tenderness in or near the region of the kidney. Pain on fist percussion of the

costovertebral angle is the most constant physical finding, often accompanied by moderate muscle rigidity in the upper abdominal and lumbar muscles. A flank mass or a bulge in the lumbar region, with loss of the natural concave lumbar outline, may be present. Examination of the chest on the affected side may be abnormal, with decreased respiratory excursion, tenderness over the lower ribs, dullness, diminished breath sounds, increased fremitus, or rales.

costovertebral angle is the most constant physical finding, often accompanied by moderate muscle rigidity in the upper abdominal and lumbar muscles. A flank mass or a bulge in the lumbar region, with loss of the natural concave lumbar outline, may be present. Examination of the chest on the affected side may be abnormal, with decreased respiratory excursion, tenderness over the lower ribs, dullness, diminished breath sounds, increased fremitus, or rales.

FIGURE 24.1 Diagram of the pathogenesis of a staphylococcal renal carbuncle. (From Andriole VT. Renal carbuncle. Medical Grand Rounds. 1983;2:259, with permission.) |

Basic laboratory data are variable. Peripheral white blood cell counts are moderately elevated in 95% of patients.9 The urinalysis usually presents no pathognomonic findings. Proteinuria, pyuria, or microscopic hematuria are usually present and a Gram stain of the urine will demonstrate the pathogen if the abscess communicates with the collecting system of the kidney. However, negative urinalyses are seen in most patients and blood cultures are usually negative.9

Diagnosis

Renal cortical abscesses must be differentiated from other space-occupying lesions in the kidney. Renal tumors, cysts, intrarenal abscesses caused by aerobic gram-negative bacilli, and perinephric abscesses can mimic renal cortical abscesses. In the past, surgical exploration was performed to differentiate the renal mass from a carcinoma. The clinical presentation of a renal cortical abscess is nonspecific and not helpful in differentiating this disease from a renal tumor or perinephric abscess. Chills, fever, malaise, and back pain may be seen in each. A renal cortical abscess on the anterior surface of the kidney may produce abdominal symptoms and lead to an erroneous diagnosis of an intra-abdominal process. Renal cortical abscesses may also be confused with abscesses of the renal medulla, particularly in children.7,9,10,11,13,14,15 Radiologic techniques can define the character of the renal mass and establish the correct diagnosis.16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25

In intravenous pyelograms, a renal cortical abscess appears as a mass of diminished density, frequently associated with distortion of the calyces, infundibulum, and renal outline. An abscess that extends to the periphery of the renal cortex may produce sufficient edema of the renal capsule to obliterate a segment of the perirenal fat shadow. However, there is no displacement of the kidney, as is frequently seen with a perinephric abscess. Thus, an abnormal intravenous pyelogram that demonstrates an intrinsic mass with calyceal distortion, but without displacement of the kidney in a patient with sterile urine, suggests a diagnosis of renal cortical abscess or tumor.

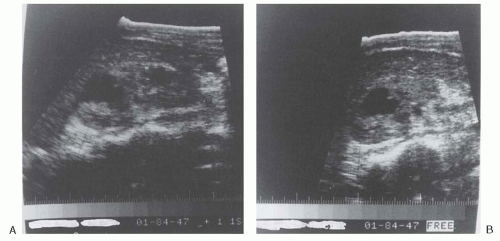

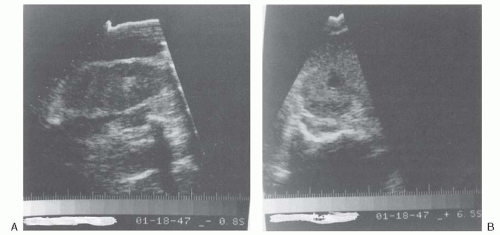

Ultrasonography has been extremely helpful in establishing the diagnosis of renal cortical abscess.9 Renal ultrasonography is easily available, cost effective, and there is no exposure to radiation or contrast. Renal ultrasonography can provide morphologic detail of the kidneys; is capable of identifying cystic lesions, tumorlike masses, or abscess cavities; and can show the size and location of the lesion. Early in the development of a renal cortical abscess, however, internal echoes may be present, giving the appearance of a solid or semisolid mass. Because these findings are compatible with either a renal cortical abscess or tumor, computed tomography (CT) may be performed to define the lesion further and to establish the correct diagnosis.26,27 Another disadvantage of renal ultrasonography is its dependence on the operator and the body habitus of the patient.27 After coalescence, an abscess can be identified by ultrasound as a fluid-filled mass with a relatively thick wall (Fig. 24.2). Ultrasonography also can be used to guide aspiration of the lesion and to follow its resolution with antibiotic treatment7,24,28 (Fig. 24.3).

CT is the most accurate noninvasive technique currently in widespread use and permits detection of abscesses smaller than 2 cm.29,30,31 Contrast-enhanced CT is useful if ultrasonography is negative or equivocal and allows for the detection of pathologic lesions in the renal cortex and medulla in early stages. CT is also useful as a guide to percutaneous aspiration of an abscess and to follow a known lesion. An abscess appears as a sharply demarcated low-density lesion on CT. The abscess does not enhance with contrast because of its avascular nature; however, the wall of the abscess enhances because of the presence of dilated and inflamed vessels.28,30,31 The finding of gas in a low density mass is pathognomonic for an abscess.30

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is another noninvasive technique that is as accurate as CT to diagnose renal abscess and define the extent of involvement. With an MRI there is no exposure to radiation and ionizing contrast.27 MRI with gadolinium and contrast-enhanced CT scans have comparable sensitivity to detect renal abscesses. Noncontrast CT and renal ultrasonography are not as good to detect renal parenchymal pathology.32 To differentiate between a renal

malignancy and an isolated abscess in the kidney, MRI with diffusion-weighted images is helpful. The principle behind this is the diffusion of water molecules is reduced in the intracellular space compared to the extracellular space. Thus, highly cellular tumors may be more likely to have restricted diffusion than less cellular tumors/masses. This modality has been used extensively to characterize central nervous system lesions.33 Several drawbacks to MRI are that it is expensive and time consuming to perform. Gadolinium use in patients with stage IV or V chronic kidney disease is also contraindicated.

malignancy and an isolated abscess in the kidney, MRI with diffusion-weighted images is helpful. The principle behind this is the diffusion of water molecules is reduced in the intracellular space compared to the extracellular space. Thus, highly cellular tumors may be more likely to have restricted diffusion than less cellular tumors/masses. This modality has been used extensively to characterize central nervous system lesions.33 Several drawbacks to MRI are that it is expensive and time consuming to perform. Gadolinium use in patients with stage IV or V chronic kidney disease is also contraindicated.

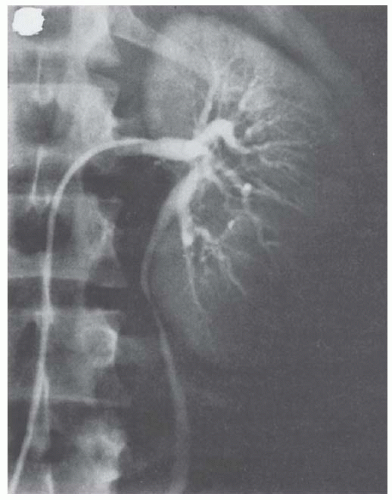

Selective renal arteriography is an older modality used to differentiate renal cortical abscess from tumor. A renal cortical abscess can be identified angiographically as a mass that produces arcing, stretching, and attenuation of adjacent arteries, with the vessels located around the circumference rather than within the mass (Fig. 24.4). Early in the course, the rim around the abscess is poorly visualized, but arterial circulation to the periphery gradually increases with time so that a late study may identify a dense rim in the parenchymal phase. An untreated abscess may progress to a stage in which the rim is thick and poorly vascularized.

FIGURE 24.3 Ultrasonogram of the right kidney after 4 weeks of antibiotic therapy (from the same patient as in Fig. 24.2). Longitudinal view (A) and transverse view (B) showing a decrease in the size of the fluid-filled echolucent lesions. (From Andriole VT. Renal carbuncle. Medical Grand Rounds. 1983;2:259, with permission.) |

Renal and perirenal abscesses can be arteriographically distinguished from tumors because the major portion of an abscess is avascular whereas the wall of the abscess is hypervascular.

Renal carcinoma may be hypervascular or hypovascular (necrotic), but rarely both. In an abscess, the arteries retain their normal organization and branching pattern. Tumor neovascularity, in contrast, consists of abnormal vessels. Tumor vessels have no recognizable organization, may enlarge instead of taper as they course peripherally, and have an abnormal branching pattern.

Renal carcinoma may be hypervascular or hypovascular (necrotic), but rarely both. In an abscess, the arteries retain their normal organization and branching pattern. Tumor neovascularity, in contrast, consists of abnormal vessels. Tumor vessels have no recognizable organization, may enlarge instead of taper as they course peripherally, and have an abnormal branching pattern.

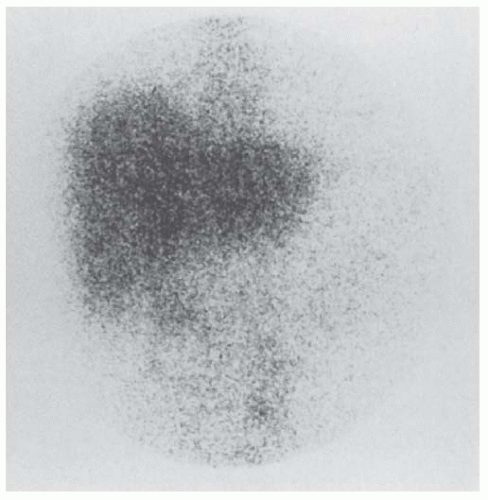

Nuclear imaging was popular before CT and MRI became widely available. Renal scanning with gallium-67 (67Ga) citrate (Fig. 24.5) also has been useful in localizing a renal abscess in adults.17,28,34 A subtraction technique using 67Ga citrate and technetium-99 (99Tc) glucoheptonate can define the extent of perinephric involvement and eliminate any false-positive scans seen with gallium alone.34 The latter may occur in patients with renal carcinoma, severe pyelonephritis without abscess formation, or ureteral obstruction.111 In-labeled white cell scanning identifies a renal abscess but does not demonstrate renal carcinoma.

Noninvasive techniques such as ultrasound, CT, and MRI have reduced the need for intravenous pyelogram, selective angiography, and nuclear imaging to further define intrarenal masses.

Radiologic techniques can correctly establish a diagnosis of a renal cortical abscess only when this diagnosis is considered. Unfortunately, clinicians generally do not think of the diagnosis of renal cortical abscess early in its course. An average delay of 62 days before the correct diagnosis was established and proper treatment instituted has been reported.9

Treatment

Historically, the treatment of a renal cortical abscess has been surgical and has varied with the condition of the patient.8 However, because a renal cortical abscess is usually hematogenous in origin, and caused by S. aureus, it often responds to antistaphylococcal antimicrobial therapy alone, thus obviating the need for surgical intervention.9

If the diagnosis of renal cortical abscess is suspected from the history, physical findings, and renal ultrasonography (abscess localized to the renal parenchyma) or CT, and gram-positive cocci or no bacteria are seen on microscopic examination of the urine, antimicrobial therapy should be directed against S. aureus. Choice of empiric antistaphylococcal therapy depends on the susceptibility patterns of S. aureus in the community. If methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) is prevalent in the community, oxacillin or nafcillin 1 to 2 grams intravenously (IV) every 4 to 6 hours is appropriate initial therapy. If a history of nonanaphylactic penicillin allergy (i.e., rash) is present, cefazolin (2 grams every 8 hours) is an alternative. Patients with severe immediate penicillin allergy may manifest cross-reacting allergy when a cephalosporin is administered and should receive vancomycin (1 gram every 12 hours) instead. If the prevalance of community-associated methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) is high, empiric therapy with vancomycin

is justified. Historically, MRSA infections have been associated with exposures to health care settings; however, since 2001, community-associated MRSA has become an increasingly recognized and prevalent pathogen.35 With the indiscriminate use of glycopeptides, vancomycin-intermediate S.aureus (VISA) and vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA) are a growing concern. Daptomycin (6 mg per kg IV every 24 hours) is the agent of choice in this setting. The prevalence of VISA and VRSA is not high enough at this time to warrant empiric therapy with daptomycin. Renal cortical abscesses can be cured with parenteral antibiotic therapy administered for a minimum of 10 days to 2 weeks, followed by oral antistaphylococcal therapy for at least an additional 2 to 4 weeks. The decision to pursue percutaneous drainage for therapeutic and/or diagnostic purposes is guided by the size of abscess and response to antimicrobial therapy. Renal abscesses less than 5 cm in size can be treated with antibiotic therapy alone.36,37 If there is optimal response, fever gradually subsides over a 5- to 6-day period without recurrence. Flank or back pain abates rather quickly, and patients display significant clinical improvement within 24 hours of initiating antibiotic therapy. A prompt response to treatment justifies continuing antibiotic therapy without surgical intervention, and serial ultrasound or CT examinations can be used to show progressive reduction and ultimate disappearance of the renal mass. A contrary clinical course should suggest misdiagnosis or uncontrolled infection, with the development of perinephritis, perinephric abscess, or infection with an organism resistant to the antibiotics being administered. In such cases, modification of therapy may be required, based on the results of cultures of blood and urine. Nevertheless, a trial of intensive antibiotic treatment is warranted in lesions measuring less than 5 cm that are localized to the renal parenchyma. If the patient does not respond within 48 hours, percutaneous, ultrasonically, or CT guided needle aspiration of the intrarenal fluid-filled lesion can be attempted.38,39,40,41 If the renal abscess measures more than 5 cm, therapeutic and diagnostic percutaneous drainage along with antibiotics should be attempted.37 If this treatment is unsuccessful, operative intervention should be undertaken.

is justified. Historically, MRSA infections have been associated with exposures to health care settings; however, since 2001, community-associated MRSA has become an increasingly recognized and prevalent pathogen.35 With the indiscriminate use of glycopeptides, vancomycin-intermediate S.aureus (VISA) and vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA) are a growing concern. Daptomycin (6 mg per kg IV every 24 hours) is the agent of choice in this setting. The prevalence of VISA and VRSA is not high enough at this time to warrant empiric therapy with daptomycin. Renal cortical abscesses can be cured with parenteral antibiotic therapy administered for a minimum of 10 days to 2 weeks, followed by oral antistaphylococcal therapy for at least an additional 2 to 4 weeks. The decision to pursue percutaneous drainage for therapeutic and/or diagnostic purposes is guided by the size of abscess and response to antimicrobial therapy. Renal abscesses less than 5 cm in size can be treated with antibiotic therapy alone.36,37 If there is optimal response, fever gradually subsides over a 5- to 6-day period without recurrence. Flank or back pain abates rather quickly, and patients display significant clinical improvement within 24 hours of initiating antibiotic therapy. A prompt response to treatment justifies continuing antibiotic therapy without surgical intervention, and serial ultrasound or CT examinations can be used to show progressive reduction and ultimate disappearance of the renal mass. A contrary clinical course should suggest misdiagnosis or uncontrolled infection, with the development of perinephritis, perinephric abscess, or infection with an organism resistant to the antibiotics being administered. In such cases, modification of therapy may be required, based on the results of cultures of blood and urine. Nevertheless, a trial of intensive antibiotic treatment is warranted in lesions measuring less than 5 cm that are localized to the renal parenchyma. If the patient does not respond within 48 hours, percutaneous, ultrasonically, or CT guided needle aspiration of the intrarenal fluid-filled lesion can be attempted.38,39,40,41 If the renal abscess measures more than 5 cm, therapeutic and diagnostic percutaneous drainage along with antibiotics should be attempted.37 If this treatment is unsuccessful, operative intervention should be undertaken.

Renal Corticomedullary Abscess

Etiology

Enteric aerobic gram-negative bacilli, predominantly Escherichia coli, Proteus spp., and, less commonly, Klebsiella spp., Enterobacter spp., and Pseudomonas spp. are usually responsible for intrarenal corticomedullary infections in association with vesicoureteral reflux or other urinary tract abnormalities.

Pathogenesis

Renal corticomedullary bacterial infections include a variety of acute and chronic parenchymal inflammatory processes. The more severe forms of these infections include acute focal bacterial nephritis, acute multifocal bacterial nephritis, and xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis, which almost always involve only one kidney.

Acute focal bacterial nephritis is an uncommon, severe form of acute infectious interstitial nephritis presenting with a renal mass caused by acute focal infection without liquefaction.42 This entity is also referred to as focal pyelonephritis or acute lobar nephronia, because the pathology consists of a heavy leukocytic infiltrate confined to a single renal lobe with focal areas of tissue necrosis.

Acute multifocal bacterial nephritis is also a severe form of acute renal infection in which a heavy leukocytic infiltrate occurs throughout the kidney with frank intrarenal abscess formation. Acute focal bacterial nephritis may represent an early phase of acute multifocal bacterial nephritis.43

Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis is a very rare and atypical form of severe chronic renal infection. Schlagenhaufer initially described the pathologic features of xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis44 in 1916. Grossly, the entire kidney or its involved segment is enlarged and may be fixed by perirenal fibrosis or retroperitoneal extension of the granulomatous process, which often resembles an inoperable tumor. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis is classified into three stages based on the extent of involvement of renal and adjacent tissue by the xanthogranulomatous process.45 In stage I (nephric), the xanthogranulomatous inflammatory process is confined to the kidney. Stage II lesions (perinephric) involve the renal parenchyma and Gerota’s fat, whereas stage III lesions (paranephric) involve the renal parenchyma and its surrounding fat with widespread retroperitoneal involvement. Each stage is further divided into focal or diffuse, depending on the amount of parenchymal involvement. Microscopically, the disease is characterized by massive tissue necrosis and phagocytosis of liberated cholesterol and other lipids by xanthoma cells (macrophages). These foamy xanthomatous histiocytes appear to simulate clear-cell renal carcinoma.46,47

Acute focal bacterial nephritis, acute multifocal bacterial nephritis, and xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis most commonly occur as a complication of bacteriuria and ascending infection, associated with tubular obstruction or scarring from prior infections, renal calculi, vesicoureteral reflux, urinary tract obstruction, or other abnormalities of the genitourinary system or in association with the endocrinopathies of diabetes mellitus or primary hyperparathyroidism.9,11,14,15,42,43,47,48,49,50,51 These predisposing factors, particularly vesicoureteral reflux in children and renal calculi or other forms of urinary obstruction in adults, lead to intrarenal reflux and provide an avenue for bacteria to inoculate the renal parenchyma. Parenchymal infection develops with abscess formation because the kidney is unable to clear the infection in the presence of reflux, urinary obstruction, medullary scarring, or other causes of tubular obstruction. In adults, two thirds of intrarenal abscesses caused by aerobic gram-negative bacilli are associated with renal calculi or damaged kidneys, whereas in children this process is often associated only with vesicoureteral reflux. The incidence of renal abscesses in patients with diabetes mellitus is twice that in nondiabetic persons. In contrast to the staphylococcal renal cortical abscess of hematogenous origin, the gram-negative bacillary corticomedullary abscess of the kidney frequently produces severe renal infection. Although renal corticomedullary infections are confined within the substance of the kidney, they may perforate the renal capsule and form a perinephric abscess, extend toward

the renal pelvis and drain into the collecting system, or develop into a chronic abscess.50 The etiology of xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis is undefined; however, it appears to be related to a combination of chronic urinary tract infection and renal obstruction. The majority of the cases have renal calculi with staghorn renal calculi being the most common type.52 Additional predisposing factors include chronic segmental or diffuse renal ischemia resulting in alterations in renal or lipid metabolism or both, lymphatic obstruction, abnormal immune response, diabetes mellitus, and primary hyperparathyroidism.47,53,54

the renal pelvis and drain into the collecting system, or develop into a chronic abscess.50 The etiology of xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis is undefined; however, it appears to be related to a combination of chronic urinary tract infection and renal obstruction. The majority of the cases have renal calculi with staghorn renal calculi being the most common type.52 Additional predisposing factors include chronic segmental or diffuse renal ischemia resulting in alterations in renal or lipid metabolism or both, lymphatic obstruction, abnormal immune response, diabetes mellitus, and primary hyperparathyroidism.47,53,54

Clinical Features

Renal corticomedullary abscesses affect males and females with equal frequency except for xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis in adults, where females are more frequently affected than males.53,54 Although these infections occur in all age groups, the incidence increases with advancing age. Peak incidence for xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis occurs in the fifth to seventh decade and has been reported to occur in transplanted kidneys as well as native kidneys.55 Most patients with acute focal bacterial nephritis, multifocal bacterial nephritis, or xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis experience fever, chills, and flank or abdominal pain. Two thirds of patients have nausea and vomiting but dysuria is not necessarily present thus mimicking an abdominal process. Some patients may have a palpable flank or abdominal mass. Clinical signs of severe urinary tract infection with urosepsis may be seen in patients with acute multifocal bacterial nephritis, half of whom have diabetes mellitus. Nonspecific constitutional complaints of malaise, fatigue, and lethargy are particularly common (74%) in patients with xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis, who may also complain of weight loss (24%). Significant physical findings include a renal mass (60%), hepatomegaly (30%), and, rarely, a draining flank sinus in patients with a past medical history of recurrent urinary tract infection (65%), renal stones (30%), or prior urinary tract instrumentation (26%). Peripheral white blood cell counts are elevated in most patients. The urinalysis is often abnormal, with pyuria, proteinuria, bacteriuria, and occasionally hematuria. However, the urinalysis may be normal in as many as 30% of patients. E. coli, Proteus mirabilis, and Klebsiella

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree