DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

■ A variety of other conditions may mimic adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder. These include benign intraluminal polyps (due to the mass appearance on imaging), chronic cholecystitis (due to collapse of the lumen and associated mural thickening due to chronic inflammation), or hepatic masses within the gallbladder fossa (due to presence of a hepatic mass adjacent to the gallbladder).3

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

■ The majority of early-stage gallbladder cancers are clinically silent and will not be diagnosed preoperatively but instead will be recognized on final pathology following cholecystectomy performed for other conditions, such as symptomatic cholelithiasis or cholecystitis.4,5

■ Occasionally, polypoid gallbladder cancers will present with right upper quadrant pain similar to cholecystitis, presumably from the intraluminal mass effect or the obstruction of the fundus/cystic duct. In addition, should the tumor extend down the cystic duct to the common hepatic duct, patients may present with painless jaundice.

■ Symptoms of abdominal bloating and/or weight loss should be concerning for the presence of malignant ascites due to peritoneal metastasis, a common site of spread. The liver is the most other common site of metastasis.

■ The incidence of gallbladder cancer is three times higher in women than in men.6

■ Hispanics, American Indians, and Mexican Indians have been identified as high-risk groups for gallbladder cancer.6

■ Large, multiple gallstones have an increased association with gallbladder cancer; gallstones are present in 60% to 80% of patients with gallbladder cancer.3

■ Obesity is a risk factor for both gallstones and gallbladder cancer; furthermore, obesity increases the risk for the development of nonalcoholic liver disease, particularly nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which may impact the suitability for radical cholecystectomy.7

■ Radical cholecystectomy involves a partial hepatic resection, and therefore, risk factors for cirrhosis (e.g., alcohol abuse, chronic hepatitis virus infection) are important aspects of the patient’s history and evaluation for tolerability of hepatic resection.8

■ Early-stage gallbladder cancer is usually not apparent on physical examination. Physical findings suggesting advanced disease include the presence of ascites (peritoneal metastasis); painless jaundice (either direct extension into the common hepatic duct or bulky portal adenopathy causing external biliary dilation); and a nontender, palpable gallbladder (concerning for extensive mural involvement). In addition, physical findings of end-stage liver disease raise the suspicion of underlying cirrhosis and therefore preclude radical cholecystectomy.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

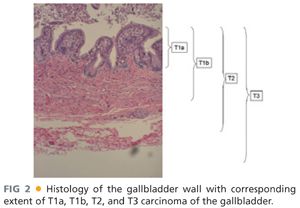

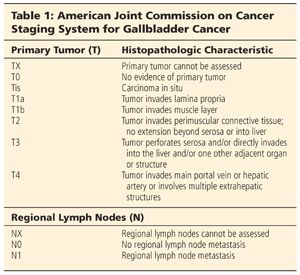

■ Radical cholecystectomy is appropriate only for those patients with T1b, T2, or T3 (primary tumor thickness) or N0 or N1 gallbladder cancer (FIG 2 and Table 1).9–14

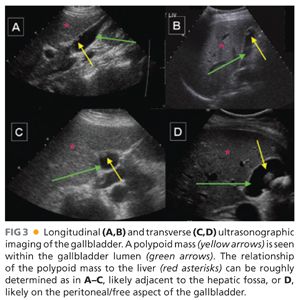

■ The majority of patients will undergo an initial ultrasound for evaluation of right upper quadrant pain and suspected cholelithiasis. The presence of a gallbladder polyp within the lumen raises the suspicion for gallbladder cancer (FIG 3). Given the intraluminal aspect of any polyp, percutaneous biopsy is not usually feasible in the absence of any invasive features beyond the gallbladder wall.15

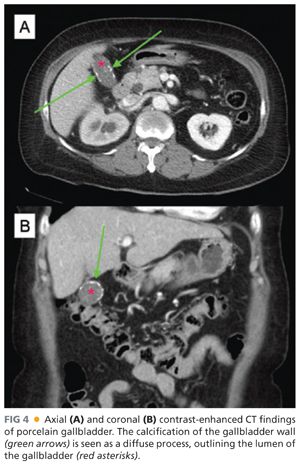

■ There is only a weak association between patients with a calcified gallbladder (“porcelain gallbladder”) and an underlying gallbladder cancer, such that prophylactic cholecystectomy may no longer be routinely advocated.16 The calcification of the gallbladder wall may not be readily visible on ultrasound but is clearly seen on contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scans (FIG 4). This radiologic finding should prompt concern for gallbladder cancer, even in the absence of any symptoms or associated findings on radiologic imaging.

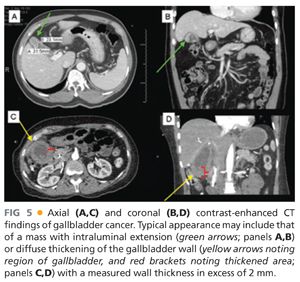

■ If history, physical examination, or ultrasound findings raise concern for gallbladder cancer, contrast-enhanced CT is useful for characterization of the extent of the gallbladder cancer. Radiologic findings of gallbladder cancer on CT include a mass within the gallbladder that typically extends into the lumen or diffuse wall thickening (FIG 5).15

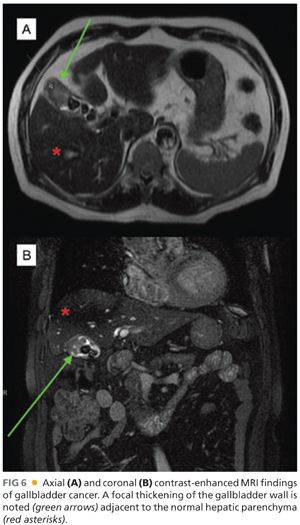

■ Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may additionally be useful to characterize any mass seen on either ultrasound or contrast-enhanced CT scan given the ability to differentiate water density (i.e., bile) as well as evaluate any potential involvement of the biliary tree through use of magnetic resonance with cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). Findings on MRI are similar to that of CT scan, including a mass within the gallbladder lumen that is distinct from the density of the hepatic parenchyma and therefore useful for the determination of direct hepatic invasion (FIG 6).17

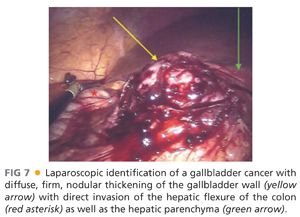

■ Unfortunately, many gallbladder cancers are not diagnosed preoperatively but identified in the final pathology specimen for early-stage disease after laparoscopic cholecystectomy for cholelithiasis; up to 10% of all laparoscopic cholecystectomies performed for benign conditions such as cholelithiasis will harbor an incidental gallbladder cancer.18 Additionally, some advanced-stage tumors may be mistaken for chronic cholecystitis preoperatively and only identified in the operating room. These tumors will have preoperative imaging of a contracted gallbladder with thickened walls. Intraoperatively, these tumors are clearly identified as malignant, with laparoscopic findings of nonpliable tissue, extremely thickened gallbladder wall, and often invasion into adjacent structures (e.g., omentum, liver, duodenum, hepatic flexure of the colon) (FIG 7).

■ The tumor markers carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) may be elevated in patients with gallbladder cancer but are neither sensitive nor specific for diagnostic purposes, or correlation with extent of disease.19

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

■

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree