Gregory A. Broderick, MD

Scientific organizations have recommended guidelines for the management of priapism including the American Urological Association in 2003 (www.auanet.org) and the International Society for Sexual Medicine in 2006 (www.issm.info). Both groups have noted that the literature on priapism is composed mainly of small case series and individual case reports and includes inconsistent definitions and methodologies with little long-term erectile function outcome data. Recent case series have included detailed methodology including duration of priapism, etiology of priapism, and erectile function outcomes. The basic science on the pathogenesis of priapism and clinical research supporting the most effective treatment strategies are summarized in this chapter. Recommendations for best clinical practice and suggestions for research are made.

Defining Priapism

Ischemic Priapism (Veno-Occlusive, Low-Flow)

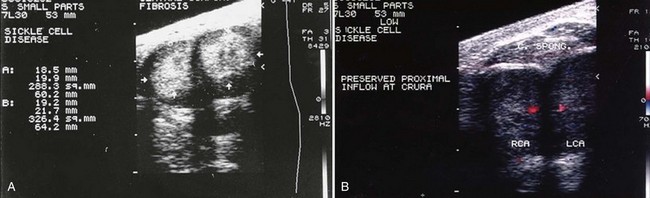

Ischemic priapism is a persistent erection marked by rigidity of the corpora cavernosa and little or no cavernous arterial inflow. In ischemic priapism there are time-dependent changes in the corporal metabolic environment with progressive hypoxia, hypercarbia, and acidosis. The patient typically complains of penile pain after 6 to 8 hours, and the examination reveals a rigid erection. The condition is analogous to a muscle compartment syndrome, with initial occlusion of venous outflow and subsequent cessation of arterial inflows. Well-documented histologic changes occur within the corporal smooth muscle as a consequence of prolonged ischemia. Interventions beyond 48 to 72 hours of onset may help relieve erection and pain but have little benefit in preserving potency. Histologically by 12 hours corporal specimens show interstial edema, progressing to destruction of sinusoidal endothelium, exposure of the basement membrane, and thrombocyte adherence at 24 hours. After 48 hours thrombus can be found in the sinusoidal spaces and smooth muscle necrosis with fibroblast-like cell transformation is evident (Spycher, 1986). Ischemic priapism is an emergency. When left untreated, resolution may take days and erectile dysfunction (ED) invariably results (Fig. 25–1A and B).

Stuttering Priapism (Intermittent)

Stuttering priapism characterizes a pattern of recurrence. The term has historically described recurrent unwanted and painful erections in men with sickle cell disease (SCD) (Serjeant, 1985). Patients typically awaken with an erection that persists for several hours. Unfortunately, males with SCD may experience stuttering priapism from childhood; in these patients the pattern of stuttering may increase in frequency and duration, leading up to a full episode of unrelenting ischemic priapism. Unfortunately, any patient who has experienced an episode of ischemic priapism is also at risk for stuttering priapism.

Priapism: Historical Perspectives

The term priapism has its origin in reference to the Greek god Priapus, who was worshipped as a god of fertility and protector of horticulture. Priapus is memorialized in sculptures for his giant phallus. The first recorded account of priapism in English medical literature appears in the Lancet and is attributed to Tripe (1845). Historically the most commonly cited observation on this condition in North American literature is Frank Hinman Senior’s landmark article describing the natural history of priapism (Hinman, 1914). Subsequently in 1960 his son Frank Hinman Jr. proposed that venous stasis, increased blood viscosity, and ischemia were responsible for priapism and emphasized that failure to correct these abnormalities in the penile environment was essentially responsible for treatment nonresponse (Hinman, 1960). Advances in our understanding of the physiology of erection and the pathophysiology of ED substantiated early hypotheses that prolonged veno-occlusion within the corporal bodies is analogous to a compartment syndrome. Hauri demonstrated the radiologic differences between veno-occlusive and arterial priapism (1983).

Frank Hinman (1914) first described “acute transitory attacks of priapism” as opposed to persistence or rapid recurrence of a single episode. The actual term of stuttering priapism is attributed to Emond and colleagues (1980) in observations of patients with SCD in a Jamaican clinic. Stuttering priapism episodes were seen to increase in frequency and length, leading to major, unrelenting occurrence of ischemic priapism. Attempts to manage SCD patients with stuttering ischemic priapism resulted in the early recommendation for hormonal suppression of nocturnal erections and stuttering with estrogen (Serjeant, 1985).

Nonischemic priapism is described far less commonly than ischemic priapism in the urologic literature. Nonischemic priapism is invariably associated with antecedent perineal or penile trauma. It was first described in the English literature by Burt (1960).

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology of Priapism

Etiology of Ischemic Priapism (Veno-Occlusive, Low-Flow)

Population-based studies estimate cases per 100,000 person-years (the number of patients with a first episode of priapism divided by the accumulated amount of person-time in the study population). Cases per 100,000 person-years have been calculated in several countries; these data depend on recording of presentations to clinics and hospitals where cases are registered. Kulmala and colleagues (1995) calculated the cases per 100,000 person-years to be 0.34 to 0.52 from 1975-1990 in Finland; Eland and colleagues (2001) calculated the cases in the Netherlands to be 1.5/100,000 person-years; Earle and colleagues (2003) calculated 0.84/100,000 person-years in Australia from 1985-2000. These reported incidences were statistically significantly impacted by the introduction and proliferation of intracavernous vasoactive injections for the management of erectile dysfunction; in Finland during the last 3 years of the study the incidence of priapism doubled to 1.1 cases/100,000 person-years. These and other reports on the epidemiology and etiology of priapism are also greatly influenced by the prevalence of SCD in the populations described. The life-time probability of a man with SCD developing ischemic priapism ranges from 29% to 42% (Emond, 1980).

In 1986 Pohl and colleagues reported on 230 cases. The etiology of priapism was identified as idiopathic in the majority, and 21% of cases were associated with alcohol or drug use/abuse, 12% with perineal trauma, and 11% with SCD (Pohl, 1986). Although SCD is a predominant etiology of veno-occlusive priapism cases in the literature, there is a wide variety of reported associations from urinary retention to insect bites (Hoover, 2004). Priapism has even been reported following spider bites and envenomation from the “Brazilian banana spider,” Phoneutria nigriventer (Andrade, 2008; Villanova, 2009). The genus Phoneutria (Greek for murderess) has eight species. P. nigriventer is known to hide in dark and moist places, wander the jungle floor, and stowaway within banana shipments. P. nigriventer is blamed for most cases of envenomation in Brazil; the venom contains a neurotoxin that has calcium channel blocking properties, inhibits glutamate release, and inhibits calcium reuptake and glutamate reuptake. Bites can cause intense pain, loss of muscle control—paralysis, breathing problems—asphyxiation, and priapism (www.wikipedia.org). Two peptides isolated from the venom of P. nigriventer have been directly linked with the induction of persistent and painful erections in mammals (Tx2-5 and TX2-6). The protein has been named eretina and has been shown to have highly specific interference at the molecular level with nitric oxide pathway (NO). Penile erection has been induced in vivo with eretina by direct intraperitoneal injection with a minimum effective dosage of 0.006 mcg/kg (Andrade, 2008).

Hematologic dyscrasias are a major risk factor for ischemic priapism. Priapism has been described as a complication of SCD, thalasssemia, hemoglobin Olmsted, and thrombophilia (Burnett, 2005). Thrombotic disease states have also been cited as precipitants of ischemic priapism: asplenism, erythropoietin use, hemodialysis with heparin use, and cessation of coumadin therapy. Intracavernous heparin given as a therapy for priapism due to rebound hypercoagulable states has actually worsened the condition (Fassbinder et al, 1976; Bschieipfer, 2001). Priapism may occur in patients with excessive white blood cell counts. The incidence of priapism in adult male patients with leukemia is 1% to 5% (Chang et al, 2003). Hyperleukocystosis causes priapism in these patients; it is believed that mechanical pressure on abdominal veins secondary to splenomegaly causes congestion of cavernous outflow and sludging of leukemic cells within the corpora cavernosa. When priapism presents in the oncology setting, evaluation and management of the predisposing condition must accompany interventions directed at the penis. In hematologic malignancies, leukaphresis and cytotoxic therapy (hydroxurea, ctosine arabinoside) may reduce the numbers of circulating white blood cells (Ponniah et al, 2004; Manuel et al, 2007). Priapism secondary to metastatic infiltrating solid lesions rather than leukemoid reaction is extremely rare. In most case reports of metastatic priapism, the primary malignancy is genitourinary (prostate and bladder). Metastatic infiltration of the penis may proceed with solid replacement or focal deposits within the corpora cavernosa, glans, and corpus spongiosum. Theoretically, metastatic deposits within the corpora could obstruct venous outflow resulting in ischemic priapism. Depending on the status of the patient, metastatic lesions may be managed expectantly, with partial or total penectomy, chemotherapy, or irradiation. These cases are too rarely and poorly described to define best practice recommendations (Robey, 1984; Chan, 1998; Guvel, 2003; Celma-Domenech, 2008) (Table 25–1).

Table 25–1 Etiologies of Priapism

| α-Adrenergic Receptor Antagonists |

| Prazosin, terazosin, doxazosin, tamsulosin |

| Antianxiety Agents |

| Hydroxyzine |

| Anticoagulants |

| Heparin, warfarin |

| Antidepressants and Antipsychotics |

| Trazodone, bupropion, fluoxetine, sertraline, lithium, clozapine, resperidone, olazapine, chlorpromazine, thoridazine, phenothaizines |

| Antihypertensives |

| Hydralazine, guanethidine, propanolol |

| Drugs (Recreational) |

| Alcohol, cocaine (intranasal and topical), crack cocaine, marijuana |

| Genitourinary |

| Straddle injury, coital injury, pelvic trauma, kick to penis/perineum, arteriovenous or arteriocavernous bypass surgery, urinary retention |

| Hematologic Dyscrasias |

| Sickle cell disease, thalassemia, granulocytic leukemia, myeloid leukemia, lymphocytic leukemia, multiple myeloma, haemoglobin Olmsted variant, fat emboli associated with hyperalimentation, hemodialysis, glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency |

| Hormones |

| Gonadotropin-releasing hormone, testosterone |

| Infectious (Toxin Mediated) |

| Scorpion sting, spider bite, rabies, malaria |

| Metabolic |

| Amyloidosis, Fabry disease, gout |

| Neoplastic (Metastatic or Regional Infiltration) |

| Prostate, urethra, testis, bladder, rectal, lung, kidney |

| Neurogenic |

| Syphilis, spinal cord injury, cauda equina compression, autonomic neuropathy, lumbar disk herniation, spinal stenosis, cerebral vascular accident, brain tumor, spinal anesthesia, cauda equina syndrome |

| Vasoactive Erectile Agents |

| Papaverine, phentolamine, prostaglandin E1, oral phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, combination intracavernous therapy |

Modified from Lue TF. Physiology of penile erection and pathophysiology of erectile dysfunction and priapism. In: Walsh PC, Retik AB, Vaughan ED, et al, editors. Campbell’s urology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002. p. 1610–96.

Sickle Cell Disease

Blood dyscrasias are a risk factor for ischemic priapism. SCD priapism has traditionally been ascribed to stagnation of blood within the sinusoids of the corpora cavernosa during physiologic erection, secondary to obstruction of venous outflow by sickled erythrocytes (Lue, 2002). Nelson and Winters described a series of cases in which SCD was the primary etiology of ischemic priapism in 23% of adults and 63% of children (Nelson, 1977). Sickle cell hemoglobinopathy accounts for at least a third of all cases of priapism, and indeed prevalence of ischemic priapism will vary significantly with the population of males in a community with SCD. From Emond and colleagues’ 1980 observational study comes the most commonly quoted incidence: Among 104 men attending an outpatient sickle cell clinic in Kingston, Jamaica the incidence of priapism in men with homozygous sickle cell (SS) disease was 42% (Emond, 1980). In a U.S. clinical series, Tarry and Duckett (1987) found that 6.4% of male children in an outpatient sickle cell clinic had history of priapism (Tarry, 1987). Adeyoju and colleagues (2002), in an international multicenter observational study of SCD, mailed or interviewed 130 patients attending SCD clinics in the United Kingdom and Nigeria. Respondents ranged in age from 4 to 66 years old with the mean age of 25. The authors cited mean age of onset of priapism as 15 years, with 75% of patients having their first episode before age 20 and rare first-time presentations by the third decade of life. In the questionnaires a clear distinction was made between acute severe prolonged priapism lasting longer than 24 hours requiring emergency attention and stuttering recurrent priapism of shorter and self-limiting duration. In this population the incidence of acute priapism was 35%; of these patients 72% gave a history of stuttering. The median frequency of occurrence of stuttering priapism was three times per month; the median duration of each espisode was 1.2 hours, with the longest being 8 hours. Precipitating events reported from greatest to least were sexual arousal/intercourse, fever, sleep, cold weather, and dehydration. Self-administered regimens were analgesics, drinking water, and exercise. Twenty-one percent of patients reporting history of priapism also reported erectile dysfunction. Only 7% of young men who had not experienced priapism were even aware that priapism was a potential complication of their SCD. On the basis of the World Health Organization global prevalence map of SCD, Aliyu (2008) estimates that 20 to 25 million individuals worldwide have homozygous SCD: 12 to 15 million in sub-Saharan Africa, 5 to 10 million in India, and 3 million in other world regions. Aliyu (2008) also found that 70,000 patients with SCD live in the United States.

The sickle cell genetic mutation is the result of a single amino acid substitution in the beta-globin subunit of haemoglobin. The clinical features are seen in homozygous SCD patients: chronic hemolysis, vascular occlusion, tissue ischemia, and end-organ damage. HbS polymerizes when deoxygenated, injuring the sickle erythrocyte, activating a cascade of hemolysis and vaso-occlusion. Membrane damage results in dense sickling of red cells, causing adhesive interactions among sickle cells, endothelial cells, and leukocytes. Hemolysis releases hemoglobin into the plasma. Free Hbg reacts with nitric oxide (NO) to produce methemoglobin and nitrate. This is a scavenging reaction; the vasodilator NO is oxidized to inert nitrate. Sickled erythrocytes release arginase-I into blood plasma, which converts L-arginine into ornithine, effectively removing substrate for NO synthesis. Oxidant radicals further reduce NO bioavailability. The combined effects of NO scavenging and arginine catabolism result in a state of NO resistance and insufficiency termed hemolysis-associated endothelial dysfunction (Morris, 2005; Rother, 2005; Kato, 2007; Aliyu, 2008).

Contemporary science implicates hemolysis and reduced nitric oxide in the pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension, leg ulcers, priapism, and stroke in SCD patients. Increased blood viscosity is believed to be responsible for painful crises, osteonecrosis, and acute chest syndrome. SCD patients with priapism have a fivefold greater risk of developing pulmonary hypertension. SCD priapism is also associated with reduced hemoglobin levels and increased hemolytic markers: reticulocyte count, bilirubin, lactate dehydrogenase, and aspartate aminotransferase (Kato, 2006). Cerebral vascular accidents are more frequent, close to episodes of full-blown priapism; the ASPEN syndrome (priapism, exchange transfusion, and neurologic events) describes cerebral vascular accidents in SCD patients who have received exchange transfusions (Siegel, 1993; Merritt, 2006). Sickle cell trait is considered a benign condition; a few complications have been associated with extreme physical exertions. There have been case reports of sickle cell trait as the predisposing factor to ischemic priapism (Larocque, 1974; Birnbaum, 2008).

Iatrogenic Priapism: Intracavernous Injections

Prolonged erection is more commonly reported than is priapism, following therapeutic or diagnostic injection of intracavernous vasoactive medications (Broderick, 2002). Despite the introduction of effective oral medications for ED in 1998, ICI remains an important therapeutic option for men with severe ED failing a phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitor or for men who cannot take PDE-5 inhibitors because they require or carry nitrates. In many communities patients receiving intracavernous medications for ED will outnumber patients with SCD. Priapism following intracavernous injection (ICI) is a problem all urologists will encounter and must be prepared to manage. In a review of worldwide reports on intracavernous injection (ICI) programs, Junemann and colleagues (1990) noted that diagnostic injection resulted in 5.3% of men getting ischemic priapism and 0.4% of men reported priapism after injecting at home (Junemann, 1990). In papaverine-based ICI programs, reports of prolonged erections and priapism are poorly distinguished and range from 0% to 35% (Broderick, 2002). In worldwide clinical trials of the Alprostadil Study Group, prolonged erection (defined as 4 to 6 hours) was 5%, and priapism (>6 hours) was described in 1% of subjects (Porst, 1996). In papaverine/phentolamine/alprostadil ICI programs prolonged erections have been reported in 5% to 35% of patients (Broderick, 2002).

Iatrogentic Priapism: Oral Phosphodiesterase Type 5 Inhibitors

All PDE5 inhibitors have similar side effects related directly to their mode of action, tissue content of substrate, and pharmacologic selectivity for type 5 inhibition versus other phosphodiesterase enzymes. Those side effects include headache, flushing, dyspepsia, rhinitis, light sensitivity, and myalgia. Morales and colleagues (1998) analyzed data from 4274 men who received double-blind treatment with sildenafil or placebo for up to 6 months and 2199 who received long-term open-label sildenafil for up to 1 year (Morales, 1998). No cases of priapism (erection lasting >4 hours) were reported. No cases of priapism were reported by Montorsi and colleagues (2004) in a multicenter, open-label, 24-month extension of 8- or 12-week double-blind, placebo-controlled studies assessing the long-term efficacy, safety, and tolerability of tadalafil in 1173 men with ED (Montorsi, 2004). Nonetheless, the INDICATION and USAGE section of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved product labeling for PDE type 5 inhibitors (USPI) does contain this warning: There have been rare reports of prolonged erection greater than 4 hours and priapism (painful erections >6 hours duration) for this class of compounds. Both the USPI and European Summary of Product Characteristics label information contain warning or precautionary language about the use of these agents in men who have conditions predisposing them to priapism. Tadalafil has recently been approved in many regions of the world for daily dosing in the management of ED and is currently being studied for use in the management of symptoms due to benign prostatic hypertrophy. Tadalafil 5-mg daily dosing caused no priapism in a phase II clinical study of 281 men with history of lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia for 6 weeks, followed by dosage escalation to 20 mg once daily for 6 weeks (McVary, 2007).

From 1999-2007 there have been at least nine case-based reports of oral phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor dosing and adult priapism and at least one pediatric case: Aoyagi (1999), Sur (2000), Kassim (2000), Goldmeier (2002), McMahon (2003), Wilt (2004), Gallati (2005), King (2005), Kumar (2005), and Wills (2007). The majority of cases reports detailing priapism following a PDE type 5 inhibitor reveal histories of men with increased risk for priapism: SCD, spinal cord injury, men who used PDE5 inhibitor recreationally, men who used PDE5 inhibitor in combination with intracavernous injection, men with history of penile trauma, men on psychotropic medications, and men abusing narcotics. Wills (2007) described a 19-month-old male child weighing 10 kg who accidentally ingested up to 6 tablets of sildenafil 50 mg. The child presented with persistent sinus tachycardia and partial erection for 24 hours; the authors presume this was a high-flow priapism (HFP) because the shaft was neither completely rigid nor painful. Erection in the child subsided spontaneously after overnight intravenous hydration and observation.

Key Points

Ischemic Priapism as a Complication of Erectile Dysfunction Therapy

Etiology of Stuttering (Intermittent) Priapism

Stuttering (intermittent) priapism describes a pattern of recurrent priapism. The term has traditionally been used to describe recurrent unwanted and painful erections in men with SCD. Patients typically awaken with an erection that persists up to 4 hours and becomes progressively painful secondary to ischemia. SCD patients may experience stuttering priapism from childhood. Any patient who has experienced ischemic priapism is at risk for stuttering priapism. Patients with stuttering priapism will experience repeated painful intermittent attacks up to several hours before remission. Affected young men suffer embarrassment, sleep deprivation, and performance anxiety with sexual partners (Chow, 2008). In a study of 130 patients with SCD, Adeyoju and colleagues (2002) reported that 46 (35%) had a history of priapism and, of these, 33 (72%) had a history of stuttering priapism. In 75% of patients the first episode of stuttering occurred before the age of 20. Two thirds of males presenting with SCD ischemic priapism will describe prior stuttering attacks (De Jesus, 2009). Commonly reported precipitants of full-blown SCD priapism are stuttering nocturnal/early morning erections, dehydration, fever, and exposure to cold.

Etiology and Pathophysiology of Nonischemic (Arterial, High-Flow) Priapism

HFP is a persistent erection caused by unregulated cavernous arterial inflow. The epidemiologic data on nonischemic priapism is almost exclusively derived from small case series or individual case reports. Nonischemic priapism is much rarer than ischemic priapism, and the etiology is largely attributed to trauma. Forces may be blunt or penetrating, resulting in laceration of the cavernous artery or one of its branches within the corpora. The etiology most commonly reported is a straddle injury to the crura. Other mechanisms include coital trauma, kicks to the penis or perineum, pelvic fractures, birth canal trauma to the newborn male, needle lacerations, complications of penile diagnostics, and vascular erosions complicating metastatic infiltration of the corpora (Witt, 1990; Brock, 1993; Dubocq, 1998; Burgu, 2007; De Jesus, 2009). Although accidential blunt trauma is the most common etiology, HFP has been described following iatrogenic injury: cold-knife urethrotomy, Nesbitt corporoplasty, and deep dorsal vein arterialization (Wolf, 1992; Liguori, 2005). Any mechanism that lacerates a cavernous artery or arteriole can produce unregulated pooling of blood in sinusoidal space with consequent erection. Nonischemic priapism is typically delayed in onset compared with the episode of blunt trauma (Ricciardi, 1993). Sustained partial erection may develop 24 hours following perineal or penile blunt trauma. It is believed that the hemodynamics of a nocturnal erection disrupts the clot and the damaged artery/arteriole ruptures; the unregulated arterial inflow creates a sinsusoidal fistula. As healing progresses with clearing of clot and necrotic smooth muscle tissue, the fistula forms a pseudocapsule. Formation of a pseudocapsule at the site of fistula may take several weeks to months.

Contemporary reports suggest that HFP may have a unique subvariety. Several authors have noted that following either aggressive medical management of ischemic priapism or surgical shunting, priapism may rapidly recur with conversion from ischemia to high flow. HFP has been reported after aspiration and injection of α-adrenergics in the management of ischemic priapism (McMahon, 2002; Rodriguez, 2006; Bertolotto, 2009). Color Doppler ultrasound has shown formation of an arteriolar-sinusoidal fistula at the site of intervention (needle laceration or shunt site) (Fig. 25–2A to C). On rare occasion following reversal of ischemic priapism, a new high-flow hemodynamic state of the cavernous arteries occurs with no evidence of fistula. This presentation of HFP should be suspected in cases where rapid recurrence, persistence of erection with partial penile rigidity, or stuttering priapism not associated with pain is evident. Nonfistula type of arterial priapism is the result of dysregulation of cavernous inflows. Nonfistula arterial priapism is a rare complication following management ischemic priapism (Seftel, 1998; Cruz-Guerra, 2004; Wallace, 2009). Penile tenderness to palpation is easily confused with the ongoing ache of persistent ischemia. Soft tissue edema and ecchymosis render the physical examination equivocal after medical and surgical maneuvers to alleviate priapism. Dysregulated arterial inflows with or without a fistula can best be distinguished from persistent ischemic priapism by color Doppler ultrasound.

Key Points

High-Flow Priapism

Priapism in Children

Priapism in children and adolescents is most commonly related to SCD. The literature suggests that the incidence of priapism in pediatric sickle cell clinics is 2% to 6% (Tarry and Duckett, 1987; De Jesus, 2009). The majority of SCD priapism is ischemic. In the newborn period, fetal hemoglobin predominates, not hemoglobin S (Burgu, 2007). SCD phenotypes related to ischemic or occlusive crises are unlikely to be evident while fetal hemoglobin persists. Newborn priapism is an extremely rare phenomenon with only limited case reports and rare application of contemporary diagnostic modalities. Erection is frequently elicited in males during the newborn period. In newborn males simple tactile stimulation such as diaper changing, bathing, and urethral catheterization may result in erection; the erection quickly subsides following cessation of stimuli. Fewer than 20 cases of newborn priapism have been reported in the literature; rarely has etiology been defined: polycythemia, blood transfusion, and birth canal trauma (Amlie, 1977; Leal, 1978; Shapiro, 1979; Walker, 1997). The majority of cases have been conservatively managed with spontaneous resolution reported from hours to days. Minimally invasive diagnostics (color Doppler ultrasound) should be performed (Pietras, 1979; Meijer, 2003). In children who develop priapism following straddle trauma, every effort should be made to localize the arteriolar-sinusoidal fistula. Hatzichristou and colleagues (2002) reported that identification of the fistula by Doppler ultrasound coupled with direct manual compression softens the high-flow erection and may speed spontaneous resolution. They suggested that this noninvasive therapy likely works in children and not adults because the perineum has considerably less subcutaneous fat and crural bodies are more easily compressed (Hatzichristou, 2002).

Molecular Basis of Ischemic and Stuttering Priapism

Advances in our understanding of the molecular basis of priapism have drawn significantly from both in vitro and in vivo experimental studies using animal models. Data on the true inciting mechanisms involved in ischemic priapism are emerging. Ischemic priapism consists of an imbalance of vasoconstrictive and vasorelaxatory mechanisms predisposing the penis to hypoxia and acidosis. In-vitro studies have demonstrated that when corporal smooth muscle strips and cultured corporal smooth muscle cells are exposed to hypoxic conditions, α-adrenergic stimulation fails to induce corporal smooth muscle contraction (Broderick, 1994; Saenz de Tejada, 1997; Muneer, 2005). Extended periods of severe anoxia significantly impair corporal smooth muscle contractility and cause significant apoptosis of smooth muscle cells and, ultimately, fibrosis of the corpora cavernosa.

In experimental animal models of ischemic priapism, lipid peroxidation, an indicator of injury induced by reactive oxygen species (ROS), and increased hemo-oxygenase expression occurs in the penis during and after ischemic priapism (Munarriz, 2003; Jin, 2008). Additional pathophysiologic mechanisms involved in the progression of ischemia-induced fibrosis are the upregulation of hypoxia-induced growth factors. TGF-β is a cytokine that is vital to tissue repair. However, excess amounts may induce tissue damage and scarring. Upregulation of TGF-β occurs during hypoxia and in response to oxidative stress (Moreland, 1995; Jin, 2008). It is hypothesized that TGF-β may be involved in the progression of the corporal smooth muscle to fibrosis (Bivalacqua, 2000; Jeong, 2004).

Transgenic mouse models of SCD manifest priapism (Beuzard, 1996; Bivalacqua, 2009). There have been two major discoveries in elucidation of the molecular mechanism of ischemic priapism. Mi and colleagues (2008) have shown that transgenic sickle cell mice corpora cavernosa have enhanced smooth muscle relaxation to electrical field stimulation. Transgenic sickle cell mice and mice lacking endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) gene expression display supraphysiologic erections and spontaneously phasic priapic activity in vivo (Bivalacqua, 2006, 2007).

Endothelial cells actively regulate basal vascular tone and vascular reactivity, by responding to mechanical forces and neuro-humoral mediators with the release of a variety of relaxing and contracting factors. In the penis the vascular endothelium is a source of vaso-relaxing factors such as NO and adenosine, as well as vaso-constrictor factors such as RhoA/Rho-kinase. Recent evidence suggests that in states of priapism there may be aberrant NO and adenosine signaling, thus identifying a potential role for NO/cGMP, as well as adenosine and RhoA/Rho-kinase signaling in the pathophysiology of ischemic priapism (Champion, 2005; Mi, 2008; Bivalacqua, 2009).

eNOS−/− mutant mice have an exaggerated erectile response to cavernous nerve stimulation and have phenotypic changes in erectile function consistent with priapism (Champion, 2005; Bivalacqua, 2006). Mice lacking the eNOS gene manifest a priapism phenotype through mechanisms involving defective phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) regulatory function in the penis, resulting from altered endothelial nitric oxide/cGMP signaling in the organ (Lin, 2003; Bivalacqua, 2006). Supporting this hypothesis, PDE5 expression is significantly reduced in corpora cavernosa smooth muscle cells (CCSMC) grown under anoxic and hypoxic cell culture conditions (Lin, 2003). In the context of molecular dysregulation, the cyclic nucleotide cGMP is produced in low steady-state amounts under the influence of priapism-related destruction of the vascular endothelium and thus reduced endothelial nitric oxide activity; this situation thereby downregulates the set point of PDE type 5 function, secondary to altered cGMP-dependent feedback control mechanisms (Champion, 2005; Bivalacqua, 2006; Burnett, 2007). Under these conditions, when NO is neuronally produced in response to an erectogenic stimulus or with nocturnal erections, cGMP production surges in a manner that leads to excessive erectile tissue relaxation because of basally insufficient PDE type 5 enzyme to degrade the cyclic nucleotide. Additionally, reduced Rho-kinase activity (contractile mediator) may contribute to the susceptibility of corporal tissue to excessive relaxation via two distinct molecular mechanisms. These two distinct molecular mechanisms may act in concert to promote stuttering ischemic priapism: enhanced vaso-relaxation by uninhibited cGMP and diminished contractile effects of Rho-kinase. Transgenic sickle cell mice also have significant reductions in penile NO/cGMP signaling leading to deficient PDE5 expression/activity, as well as reduced RhoA/Rho-kinase expression from which they manifest enhanced erectile responses and recurrent priapism (Champion, 2005). Another potential cause of enhanced corporal smooth muscle relaxation in SCD-associated priapism is elevated penile adenosine levels, thus causing the corpora cavernosa to be in a chronically vasodilated state (Mi, 2008). Taken together, these data suggest that ischemic priapism and most importantly stuttering priapism is a direct result of NO imbalance resulting in aberrant molecular signaling, PDE5 dysregulation, adenosine overproduction, and reductions in Rho-kinase activity, translating into enhanced corporal smooth muscle relaxation and inhibition of vasoconstriction in the penis.

Key Points

Sickle Cell Disease and Priapism

Evaluation and Diagnosis of Priapism

History

In order to initiate appropriate management, the physician must determine whether the underlying priapism hemodynamics are ischemic or nonischemic. Emergency management of ischemic priapism is recommended. Ischemia should be suspected when the patient has progressive penile pain, associated with the duration of erection; has used a known drug associated with priapism; has SCD or another blood dyscrasia; or has a known neurologic condition, especially those affecting the spinal cord. Stuttering priapism history is one of recurrent episodes of prolonged erections, usually nonresolving morning erections. Nonischemic priapism should be suspected when there is no pain and the erection duration has not been accompanied by progressive discomfort. There is a history of straddle injury, coital trauma, blunt trauma to the penis or perineum, penile injection, penile surgery or a diagnostic procedure of the pelvic and penile vessels. The onset of post-traumatic HFP in adults and children may be delayed by hours to several days following the initial injury (Table 25–2).

Table 25–2 Elements in Taking the History of Priapism

Physical Examination

Inspection and palpation of the penis is recommended to determine the extent and degree of tumescence and rigidity; the involvement of the cavernous bodies; the presence of pain; and the evidence of trauma to the perineum. In ischemic priapism the corporal bodies will be completely rigid; the glans penis and corpus spongiosum are not. Although malignancies rarely cause priapism, examination of the abdomen, testicles, perineum, rectum, and prostate may help identify a cancer primary. Malignant infiltration of the penis causes indurated nodules within or replacing corporal tissue. The subtle differences in the penile examination may be apparent to the experienced urologist but can be overlooked by emergency personnel on initial evaluation (Fig. 25–3A and B

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree