John P. Mulhall, MD, MSc (Anat)

Physiology of Ejaculation

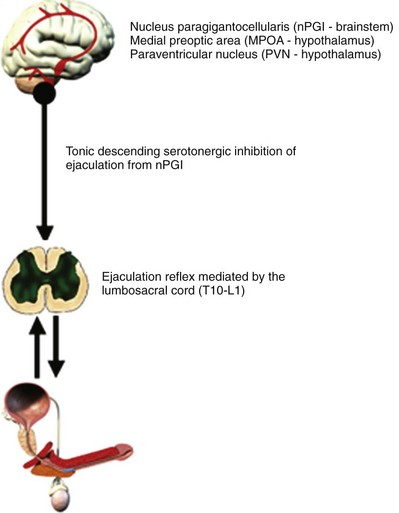

Alongside developments in the field of erectile physiology and pathophysiology, the past decade has witnessed increased understanding of central and peripheral mechanisms involved in ejaculatory control. Usually accompanied by orgasm, ejaculation constitutes the final phase of the sexual response cycle in the male and represents a reflex comprising sensory stimuli, cerebral and spinal control centers, and efferent pathways. Ejaculation is a reflex, which requires a complex interplay among somatic, sympathetic, and parasympathetic pathways involving predominantly central dopaminergic and serotonergic neurons (McMahon et al, 2004). In antegrade ejaculation, two basic phases are involved: emission and expulsion (Giuliano, 2005). Emission, as the first phase of ejaculation, is a sympathetic spinal cord reflex and defined as the deposition of seminal fluid into the posterior urethra. Expulsion is due to the combined action of sympathetic and somatic pathways. An antegrade ejaculation requires a synchronized interplay between periurethral muscle contractions and bladder neck closure, contemporaneous with the relaxation of the external urinary sphincter. Orgasm, generally associated with ejaculation, is a pleasurable sensation resulting from cerebral processing of the increased pressure in the posterior urethra and contraction of the bulbar urethra bulb and accessory sexual organs.

Coordination of Ejaculation

Peripheral and central centers, as well as sympathetic, parasympathetic, and somatic pathways, participate in the physiologic control of the ejaculatory reflex (Fig. 26–1 on Expert Consult website![]() ). A normal ejaculatory response requires synchronized neurochemical interplay coordinated at different levels of the nervous system (Giuliano, 2005). In humans, the composition of the ejaculate is released from participating organs in a particular order. The first portion of the ejaculate is provided by the bulbourethral glands followed by some fluid from the prostate. Afterwards, the main fraction of the ejaculate including the bulk of the spermatozoa is contributed by the epididymis and vas deferens, along with prostate and seminal vesicle contributions.

). A normal ejaculatory response requires synchronized neurochemical interplay coordinated at different levels of the nervous system (Giuliano, 2005). In humans, the composition of the ejaculate is released from participating organs in a particular order. The first portion of the ejaculate is provided by the bulbourethral glands followed by some fluid from the prostate. Afterwards, the main fraction of the ejaculate including the bulk of the spermatozoa is contributed by the epididymis and vas deferens, along with prostate and seminal vesicle contributions.

Adequate sensory stimulation of the dorsal penile nerve and posterior urethral distention appears to be sufficient to trigger an ejaculatory response. McKenna, describing a urethrogenital reflex, showed that urethral distension in anesthetized rats induced contractions of the striated perineal muscles (McKenna et al, 1991). The emission of the seminal fluid is controlled by the sympathetic nervous system activating propulsive contraction of the smooth muscle of the prostate, vas deferens, and seminal vesicles, as well as prostatic glandular secretion. Clear clinical evidence for a functional role of parasympathetic innervation involved in the ejaculatory process is missing thus far (Giuliano, 2005). The important role of the sympathetic system in the ejaculatory process in humans is emphasized by the fact that an interruption of the innervation of the bladder neck, vas deferens, and prostate might lead to a retrograde ejaculation or failure of emission. Protection of sympathetic efferents during surgical procedures in the retroperitoneum or in the pelvis preserves normal ejaculatory function. In patients with spinal cord injury, ejaculation can be achieved acquiring a semen sample with electric stimulation of the hypogastric plexus activating sympathetic efferents (Ohl et al, 1997, 2001).

Using positron emission tomography (PET) scanning, the areas of the brain most activated during ejaculation include the mesodiencephalic transition zone including the ventral tegmental area (VTA), medial and lateral thalamus, and SPFp (Holstege et al, 2003). Other PET and functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies have suggested that there is intense activation of the parietal cortex during ejaculation (Arnow et al, 2002; Holstege et al, 2003). This site appears to receive sensory signals from the pudendal sensory nerve fibers (Perretti et al, 2003). The VTA zone contains A10 dopaminergic neurons, purported to be involved in rewarding behaviors (also activated by cocaine).

Neuropharmacology of Ejaculation

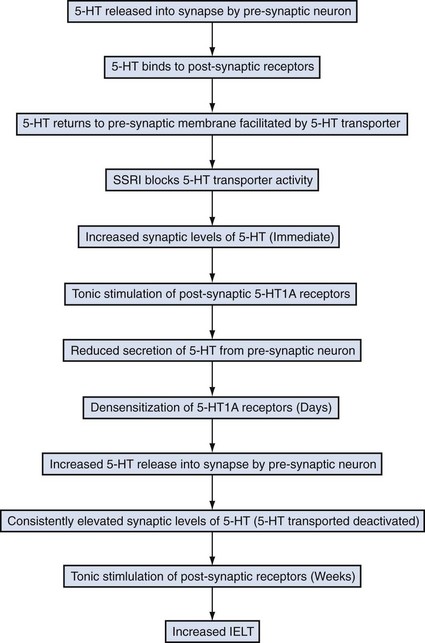

Experimental studies in animals advocate a fundamental role for dopamine (D) and serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) in the regulation of ejaculation. Cerebral serotonin (5-HT) plays an inhibitory role in ejaculation, demonstrated in several animal studies in rats (Giuliano and Clement, 2006). Within the group of 14 different 5-HT receptor subtypes, some subtypes may have proejaculatory and other antiejaculatory effects. Current literature supports at least the involvement of 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, and 5-HT2C receptors in ejaculatory control (Waldinger et al, 2004a). The stimulation of 5-HT1A receptors at various places including cerebral, spinal, or peripheral autonomic ganglia has a generally positive effect on ejaculation, whereas stimulation of 5-HT2C has the opposite effect. Activation of 5-HT1A autoreceptors has resulted in shortening of the ejaculatory latency time. On the other hand, the stimulation of presynaptic 5-HT1B autoreceptors and postsynaptic 5-HT2C receptors has shown an inhibition of ejaculatory behavior in male rats. Serotonergic neurons originate adjacent to the reticular formation in the brainstem and are self-regulated via a negative feedback system.

Serotonin is released into the synapse by the presynaptic neuron (Fig. 26–2). Once in the synapse, serotonin binds to receptors located on the postsynaptic membrane. Following this, serotonin returns to the presynaptic neuron. The return of serotonin to the presynaptic neuron is assisted by serotonin transporters. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) medications block serotonin transporters, thus preventing the reabsorption of serotonin into the presynaptic neuron. In the immediate term, there are increased levels of serotonin in the synapse. Due to this increased synaptic serotonin level, 5-HT1A receptors and 5-HT1B receptors on the postsynaptic and presynaptic membranes, respectively, become activated, resulting in a reduction in secretion of serotonin into the synapse. These receptors then become desensitized (failure of inhibition of serotonin secretion from the presynaptic neuron), resulting in the serotonin release into the synapse, but this time because of transporter inhibition by the SSRI, the synaptic serotonin levels remain high, resulting in persistent activation of postsynaptic receptors, which translates into the clinical effects of SSRI medications including prolongation of ejaculatory latency time.

Definition of Premature Ejaculation

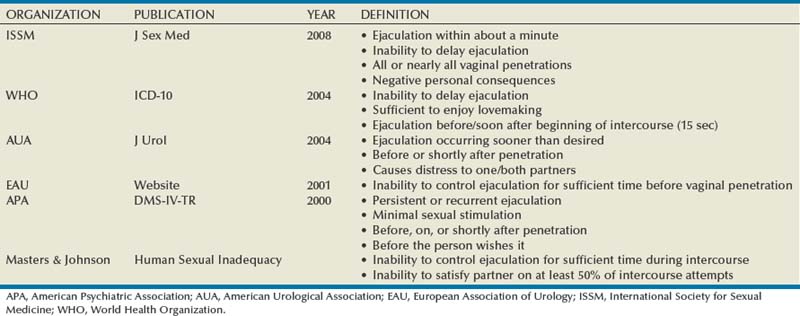

In 1943 Shapiro published the first report on premature ejaculation (PE; synonyms rapid ejaculation, ejaculatio praecox), reporting on more than 1000 men with this condition (Optale, 1943). Between then and the publication of Seaman’s seminal paper (Semans, 1956), little appeared in the literature. Since that time, the definition of PE has been a source of debate for clinicians and researchers and has undergone radical review in the past few years, culminating in a new definition developed by a consensus panel of the International Society for Sexual Medicine (ISSM) (McMahon et al, 2008). Shapiro discussed PE of types A and B in his 1943 article. These types became retermed in 1989 as life-long (also termed primary) and acquired (also termed secondary) by Godpodinoff (1989). Historically, there are numerous definitions, some defined by individuals, some by professional organizations (Table 26–1). The two definitions for PE that have been used most often have come from the American Psychiatric Association and the World Health Organization. Both groups used expert panels to arrive at their definitions, and both were devoid of any evidence-based medicine to support such definitions. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM IV) overseen by the American Psychiatric Association, the PE definition has as its core element the concept of “patient distress or interpersonal difficulty.” According to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), a time cutoff is used and the time limit arrived at was 15 seconds, without any validation of this time point.

No single factor defines PE, and the definition should involve multiple dimensions such as time, perceived control over ejaculation, personal and partner distress, reduced sexual satisfaction, and relationship difficulty (Waldinger, 2007a). Time is measured by the intravaginal ejaculatory latency time (IELT, also known as IVELT), the duration in seconds or minutes that pass from the first moment of vaginal penetration to ejaculation/orgasm. Waldinger has made a cogent argument that there is a difference between a disorder (all men with PE) and a dysfunction (those bothered by their PE) (Waldinger, 2007a). Thus given that previous definitions are based on expert opinion and are not based on epidemiologic or controlled studies, the ISSM set forth to convene a panel of experts in 2007 to review the current medical literature and to arrive at a functional definition for lifelong PE. The panel defined PE as having three components: (1) ejaculation that always or nearly always occurs before or within about 1 minute of vaginal penetration, (2) the inability to delay ejaculation on all or nearly all vaginal penetrations, and (3) negative personal consequences such as distress, bother, frustration, and/or the avoidance of sexual intimacy.

A recent proposal has been put forth by Waldinger to categorize PE into four subtypes: lifelong, acquired, natural variable PE, and premature-like ejaculatory dysfunction (Table 26–2) (Waldinger, 2007a). This subcategorization has clinical utility because as a group these categories describe nearly all patients seen in clinical practice.

Table 26–2 Variations of Premature Ejaculation

| TYPE | FEATURES |

|---|---|

| Lifelong | |

| Acquired | |

| Natural variable | |

| Premature-like ejaculatory dysfunction |

Adapted from Waldinger MD. Premature ejaculation: state of the art. Urol Clin North Am 2007;34:591–9, vii–viii.

Epidemiology

Prevalence

In the Multicountry Concept Evaluation and Assessment of PE (MCCA-PE) study, the self-reported time taken for an average man to ejaculate varied greatly from 7 to 14 minutes (Montorsi, 2005). These figures were highly geography dependent, being shorter in Germany (7 minutes), longer in the United States (14 minutes), and average in England, France, and Italy (10 minutes). Furthermore, the partners’ estimates were also country dependent with North American women estimating coital times lower than that of their male partners and German women estimating coital times higher than their partners.

Over the course of the past 5 years our understanding of the epidemiology of PE has been expanded significantly by several prospectively conducted studies. Further discussion and data on this topic (including Fig. 26–3 and Table 26–3) are included on the Expert Consult website![]() .

.

One of the first large-scale prospective studies to assess the prevalence of PE was the National Health and Social Life Survey conducted in the early 1990s (Laumann et al, 1999). This study was based on interviews, and one of the sexual issues assessed in the study was PE. This survey used a sample of 3442 men aged 19 to 59 years. Subjects were questioned regarding “climaxing too early” over the course of the preceding 12 months. The prevalence of PE in the study was 29%. Of note, there appeared to be no significant impact of age on the PE prevalence, although no attempt was made to differentiate lifelong versus acquired types of PE.

(From Patrick DL, Althof SE, Pryor JL, et al. Premature ejaculation: an observational study of men and their partners. J Sex Med 2005;2:358–67.)

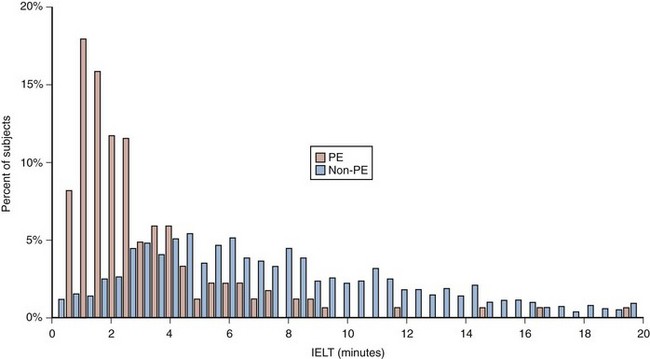

Patrick and colleagues in 2005 conducted a Johnson & Johnson–sponsored, multicenter observational study conducted at 42 U.S. medical centers (Patrick et al, 2005). PE was defined according to DSM-IV criteria. The study couples were required to engage in regular sexual intercourse to record stopwatch-measured intravaginal ejaculatory latency time (IELT), and at each sexual attempt they completed a questionnaire including key patient report outcome (PRO) measures including control over ejaculation, satisfaction with sexual intercourse, personal distress, interpersonal difficulty, and severity of premature ejaculation. Of the 1587 subjects enrolled in the study, the prevalence of PE was 13%. Subjects in the PE group had significantly shorter IELT compared with subjects in the non-PE group. The median IELT value was 2 minutes for the PE group compared with 7 minutes for the non-PE group. However, significant overlap existed in the distribution of IELT values between the two groups (Fig. 26–3). Of subjects in the non-PE group, 95% had IELT values of at least 2 minutes, while only 50% of subjects in a PE group met that threshold. Subjects in the PE group reported lower mean ratings in all PROs compared with the non-PE group. The most important finding from the study is that although the results demonstrated that IELT measured and recorded by the female partner using a stopwatch was capable of distinguishing between PE and non-PE populations, IELT alone could not be used to define PE.

In the Pfizer-sponsored Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors (GSSAB), Laumann and colleagues (2005) conducted an international poll of 13,618 male subjects in 29 countries. Subjects were questioned in either face-to-face or telephone interviews and in certain countries by mailed questionnaires. The prevalence of PE, which in this analysis was defined using a single question regarding “achieving orgasm too quickly,” ranged from 20% to 30% with significant geographic variation. In this analysis the lowest prevalence of PE was reported in the Middle East at 12%, while the highest prevalence occurred in Southeast Asia at 30%.

Fasolo and colleagues evaluated 12,558 men presenting to 186 sexual medicine clinics during the Italian Andrology Society’s Prevention Week and found a prevalence of PE of 21% using DSM-IV criteria (Basile Fasolo et al, 2005). Interestingly, in this analysis 70% of the PE patients had acquired PE. Although on initial analysis, men with PE appeared to be younger than those without PE, following adjustment for concomitant erectile dysfunction (ED), the risk of PE significantly decreased with aging. As with the U.S.-based National Health and Social Life Survey, divorce appeared to increase the risk of PE, but in contrast to the U.S. study, PE was more common among more educated men.

Porst and colleagues in the Johnson & Johnson–sponsored Premature Ejaculation Problems and Attitudes (PEPA) study recruited 12,133 men using a web-based survey conducted in three countries (United States, Germany, Italy) (Porst et al, 2007). PE in this study was defined using two proprietary questions, one regarding ejaculatory control and the other bother. The sample was believed to be representative of the overall male population of each country on the basis of census data. Overall respondents were 42 years of age with a reported partner age of 39 years. The prevalence of PE in this analysis was 23%. Roughly half of men had lifelong PE, approximately one third reported that they had acquired PE, and the remaining 15% indicated that PE had been present when they first began having sex and then went away and returned again more recently. In this analysis there appeared to be no significant variations between countries and no variation with age, although men with PE were more likely to experience other sexual dysfunctions (ED, libido alterations).

Giuliano and colleagues (2008) conducted a study in Europe similar to the aforementioned Patrick study. The study was a prospective, observational study at 44 centers in five European countries. As with the Patrick study, stopwatch IELT and PRO measures were used as end points in 1115 men. Using DSM-IV criteria, the prevalence of PE was 18%. In the PE group, mean IELT values were less than 2 minutes and were observed in 75% of the group. In the non-PE group, mean IELT values less than 2 minutes occurred in 25% of men. Men with PE with partners reported a significant negative impact of the condition on the relationship similar to findings in the Patrick study. This study showed that a man’s perception of his control over ejaculation has a significant negative effect on the satisfaction with sexual intercourse and personal distress related to ejaculation. As with the Patrick study, IELT alone could not be used to define PE. Although other studies have been done estimating PE rates of approximately 20% to 30%, they have been mostly smaller in size, retrospective in nature, less rigorously done, or conducted in special populations.

Impact of Premature Ejaculation

PE burdens the patient on two different levels: emotional and relational (Sotomayor, 2005). Men have a sense of shame and embarrassment at not being able to satisfy their partner and they often have low self-esteem and feelings of inferiority. These findings are supported by the study of Symonds and colleagues (2003), which conducted 28 in-person interviews of men with self-reported PE in the United States. The main concern for these patients was erosion of sexual self-confidence, and two thirds of the interviewees mentioned that sexual and general confidence was affected by their PE. Anxiety was also common in these PE patients with one third of interviewees specifically linking their anxiety to PE. The Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors demonstrated that PE may result in depressive symptoms in some men (Laumann et al, 2005).

The impact of PE on relationships is an important consideration for men with PE and a significant driver for treatment seeking. Rowland and colleagues (2007) reported that men with PE are more likely to report being dissatisfied with their sexual relationship compared with men without PE. The PE patients may find it difficult to initiate and maintain relationships. Women’s feelings about their partners’ PE range from understanding and support to anger and frustration. Often the man is perceived as selfish, and women have difficulty realizing that many men have poor control over their ejaculation and that they feel badly about the condition. Rowland and colleagues, in a subanalysis of the original Patrick data, assessed the psychologic burden of PE. In this analysis, a number of questionnaires were administered to patients including the Premature Ejaculation Profile (PEP) and the Self-Esteem And Relationship (SEAR) questionnaire. Overall, all inventory scores indicated significantly worse sexual functioning and satisfaction in men with PE compared with those without PE.

In the Patrick study the PRO inventory (Patrick et al, 2009) used demonstrated higher levels of distress in men with PE compared with those without PE (Patrick et al, 2005). Distress was also experienced by partners. These findings were confirmed in the counterpart European study (Giuliano et al, 2008). In an earlier U.S. Internet-based survey, men with PE reported that they had difficulty relaxing in sexual situations and were more anxious about sexual intercourse compared with a non-PE group (Rowland et al, 2004). The PEPA study (Porst et al, 2007) showed a greater percentage of men with PE reported anxiety, depression, and psychologic distress compared with men who did not have PE.

Pathophysiology of Premature Ejaculation

As the biologic mechanisms involved in ejaculatory function and dysfunction become clearer, a greater understanding of the pathophysiology of PE is being appreciated. Although there has been significant research in this area in recent times, a complete understanding of the pathophysiologic mechanisms involved in PE has not yet been achieved. The final common pathway in the genesis of PE appears to be either a hyposensitivity of 5-HT2C receptors or a hypersensitivity of the 5-HT1A receptors (Waldinger, 2002). It is believed that the ejaculatory threshold for men with low 5-HT levels and/or 5-HT2C receptor hyposensitivity may be genetically set at a lower point, resulting in more rapid ejaculation. In contrast, men with a high set point may experience delayed ejaculation. This theory is supported in part by research that has demonstrated the efficacy of SSRI medications in inhibiting PE.

Genetic Factors

In the 1940s Shapiro first noted a familial predisposition to PE, and more than half a century later, Waldinger found that 10 of 14 first-degree male relatives of men with lifelong PE had PE themselves (Waldinger et al, 2004b). More recent data confirm the concept that genetics have at least a contributory role in this condition. Jern and colleagues (2007, 2009), in a Finnish study of a population-based sample of twins using confirmatory factor analysis, suggested that genetic factors play a significant role in the pathophysiology of PE.

In Caucasians the genotypic frequencies are approximately 25% SS, 50% SL, and 25% LL. Theoretically, men with one or more S alleles for the 5-HTT have fewer functioning receptors, which could result in a higher serotonergic neurotransmission and thus longer IELTs than men with the LL genotype. Janssen and colleagues compared men with lifelong PE to a control group and demonstrated no statistically significant differences in the distribution of the 5-HTTLPR genotypes between those men with PE and those without (Janssen et al, 2009). However, in men with PE, analysis of the correlation between IELT and genotype revealed significant reduction in IELT (13 seconds) in men with the LL allele compared with those men with either the SL or SS allele (25 seconds). Although one could argue that these differences are probably not clinically meaningful, this is the first analysis demonstrating in men with lifelong PE that there may be an underlying genetic predisposition. Yet it is unlikely that this would be the only genetic factor involved in the regulation of IELT.

Psychologic Factors

Historically a number of potential psychologic explanations for PE have been proposed. It is suggested that the sympathetic nervous system, activated by anxiety, may result in an earlier emission phase of ejaculation and subsequently reduced ejaculatory threshold. Corona and colleagues studied 755 patients attending an outpatient clinic for sexual dysfunction and administered a validated multidimensional questionnaire. Twenty-eight percent of participants reported suffering from PE. Compared with non-PE patients, there was an increased prevalence of anxiety symptoms in the PE group. In a second study, evaluating 822 patients with ED and PE, validated instruments were used and showed that anxiety measures were significantly elevated in patients with PE (Corona et al, 2006). Furthermore, there was a significant correlation between the presence of PE and life stressors such as dissatisfaction at work or with key relationships. Finally, it has been suggested that men with PE have a hyperexcitable ejaculatory reflex, resulting in faster emission and/or expulsion. In addition, it has been proposed that men with PE may have a faster bulbocavernosus reflex, impairing their ability to learn to control ejaculation.

Hormone Alterations

One the first hormone avenues explored in the genesis of PE is the protein leptin. Leptin was discovered in 1994 as the product of the Ob gene. Its primary role is to provide information on the amount of body fat to the hypothalamus, thereby modulating central nervous system function that regulates food intake and energy balance. A small number of studies have explored the role of leptin in PE. Atmaca and colleagues demonstrated that serum leptin levels in patients with PE were significant higher than healthy controls and that the levels were negatively correlated with IELT values (Atmaca et al, 2002

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree