INCIDENCE AND DIAGNOSIS

Infertility is common in dialysis patients, with the incidence of pregnancy in end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) being approximately 2.2% per year in the United States (5).The luteal hormone surge and the estradiol peak that occurs mid to late menstruation with ovulation are absent in uremia, possibly due to the hyperprolactinemic state found in ESKD (6,7). While transplantation is the most effective way to restore fertility in these patients, intensification of the dialysis prescription by switching from intermittent dialysis to nocturnal hemodialysis increased the conception rate to 16.5% in a small series (8). The preponderance of anovulatory cycles with dialysis makes amenorrhea difficult to interpret in women with suspected pregnancy. While this should be investigated with β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) serum testing, caution should be exercised when interpreting hCG test results in ESKD owing to high number of false-positive results (7). The half-life of circulating hCG is increased in these patients, making the test unreliable for calculation of gestational age as well. Obstetric ultrasound is favored for estimation of gestational age in pregnant women with ESKD, with the mean gestational age at which the diagnosis of pregnancy is made being 16.5 weeks (9).

DIALYSIS PRESCRIPTION IN THE PREGNANT PATIENT

DIALYSIS PRESCRIPTION IN THE PREGNANT PATIENT

Poor outcomes for pregnancy in ESKD have been attributed to uremia-induced disturbances in hormonal homeostasis and the ensuing effects on placentation and fetal growth. The increasing success with fetal and maternal outcomes with dialysis over the last decade are largely due to intensification of the dialysis prescription, with the best results coming from long, nocturnal dialysis–based regimens (8,10,11). Nocturnal dialysis with a mean dialysis duration of 36 hours preconception and 48 hours during pregnancy in a cohort of seven pregnancies resulted in a mean gestational age of 36.2 weeks and a mean birth weight of 2,417.5 ± 657 g (8). In a study by Hladunewich et al. (4) that compared outcomes between a Canadian and American cohort of pregnant dialysis women, the live birth rates were 86.4% and 61.4%, respectively (p= 0.03), and the mean gestational ages was 36.2 weeks and 27 weeks, respectively (p= 0.002) (4). Notably, the Canadian cohort received a mean of 43 hours of dialysis compared to the 17 hours provided in the United States (4). Intense dialysis regimens of five to seven times a week, with each session lasting 8 to 10 hours, are associated with improved outcomes leading to improved live birth rates, decrease in prematurity, and improved blood pressure (BP) control. Intensive dialysis improves urea clearance, lowers peripheral vascular resistance, and ameliorates fluctuations in volume status (12,13). Daily dialysis offers the advantage of decreased risk of hypotension owing to decreased fluid removal per session and allows for high protein intake to meet caloric needs of the fetus and mother. It is also hypothesized that increased solute clearance with daily dialysis reduces placental urea and thus reduces fetal osmotic diuresis and resulting complications such as polyhydramnios (12).

While maternal and fetal outcomes do not significantly differ between hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis (9), intensification of the dialysis prescription is easier on hemodialysis. As with hemodialysis, a patient’s treatment requirements will increase with peritoneal dialysis especially during the latter half of gestation (14). A switch to continuous cyclical peritoneal dialysis (CCPD) with an increased frequency of small volume exchanges, with supplemental manual exchanges, is often required in late pregnancy to achieve adequate clearance (14). Using tidal peritoneal dialysis to successfully optimize solute clearance in pregnancy with restricted abdominal volumes has been reported (15). There are no changes in peritoneal dialysis efficacy in pregnancy as measured by a standard peritoneal equilibration test (PET) of glucose and creatinine and ultrafiltration efficacy (14). Rarely, complications such as lacerations of the gravid uterine veins from trauma to the peritoneal dialysis catheter and preterm delivery from peritonitis during pregnancy have been reported (14).

Dialyzers used during pregnancy range from standard high-flux dialyzers to nonreusable biocompatible dialyzers with blood flows ranging from 200 to 400 mL/min (4). There is little data reported on vascular access for maintenance hemodialysis in pregnancy influencing the outcome. In patients dialyzing with arteriovenous fistulae, the risk of aneurysmal dilation of the fistula due to histologic changes in the vessel wall associated with the hormonal changes in pregnancy and altered pregnancy-related hemodynamics must be factored into the routine examination of the pregnant dialysis patient (16). Heparin does not cross the placental barrier and can be used safely with hemodialysis in pregnancy, without necessitating a dose reduction.

The physiologic weight gain associated with pregnancy, which is recommended to be 1 to 1.5 kg within the first trimester and thereafter 0.3 to 0.5 kg/wk (9), should be factored into dry weight assessment. With daily dialysis, fluid gains should be minimal, and BP goals of <140/90 mm Hg should be achievable with minimal antihypertensives (9). Persistent elevations in BP despite optimal fluid removal should raise the suspicion of preeclampsia.

Target values of the main laboratory parameters suggested for pregnant women on dialysis are similar to those advised in nonpregnant dialysis patients. The pregnant patient is predisposed to respiratory alkalosis as a result of progesterone-induced hyperventilation. Hence, a bicarbonate solution concentration as low as 25 mM is preferred to standard higher concentrations to avoid superimposed metabolic alkalosis (9). With a standard 2.5 mEq/L calcium dialysate solution, the mother will need 2 g of oral calcium per day to keep a positive calcium balance and ensure the fetal calcium requirement of 25 to 30 g during pregnancy (17). The placenta secretes calcitriol which also aids in positive calcium balance.

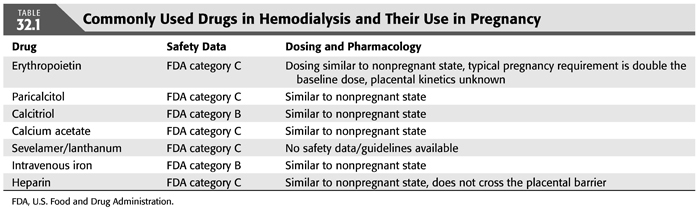

Intensive dialysis regimens during pregnancy can result in hypophosphatemia. Most patients often do not require any phosphate binders, and at times, addition of phosphorus to the dialysate may be necessary (18). In patients with hyperphosphatemia, calcium-containing binders are preferred due to their safety profile (9). There is no experience with sevelamer or lanthanum in pregnancy (9). There is limited data currently on the effects of pregnancy on dialysis-associated metabolic bone disease profiles. Activated vitamin D analogs such as paricalcitol (pregnancy category C) and calcitriol (pregnancy category B) are dosed based on the individual nephrologist’s discretion (TABLE 32.1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree