1. Ensure good blood supply (pulsatile bleeding from marginal artery at level of anastomosis)

2. Ensure tension-free anastomosis by complete mobilization of splenic flexure (includes high ligation of inferior mesenteric artery and ligation of inferior mesenteric vein at lower border of pancreas)

3. Avoid use of sigmoid colon in creation of anastomoses

4. Inspection of anastomotic donuts for completeness after circular-stapled anastomoses

5. Air or fluid insufflation test to rule out anastomotic leak immediately after construction in the operating room

Bleeding

Most anastomotic bleeding is minor and manifested by dark blood mixed in the first bowel movement after surgery.

Bleeding can occur after a stapled or handsewn anastomosis but is probably more common after one is stapled. Careful inspection can allow intraoperative control of the bleeding and reduce the postoperative risk. Also stapling a side-to-side anastomosis using the antimesenteric border (avoiding inclusion of the mesentery) reduces the risk of bleeding.

Bleeding points on a stapled anastomosis should be controlled with a suture rather than the Bovie as a deep burn injury may lead to a delayed leak. Full-thickness staple line reinforcement with interrupted sutures can help ensure optimal hemostasis.

Delayed detection of bleeding from a circular stapler or staple line of a J pouch (ileal or colonic) may need to be addressed on the ward. Steps to control bleeding include:

1.

Proctoscopy is done to evacuate all clots.

2.

A rectal tube (or Foley) is inserted and 1:100,000 epinephrine solution is instilled. The tube is clamped and the solution remains in the rectum/neorectum for 15 min.

3.

If the bleeding persists, the procedure is repeated. Endoscopic cautery or epinephrine injection is another option.

4.

If the bleeding continues to persist or the patient has hypotension, a transanal examination in the operating room is carried out.

Treatment for delayed bleeding from an inaccessible anastomosis (such as an ileocolic) usually begins with supportive care including correction of any coagulopathy.

Angiography may be required to localize the site and allow selective vasopressin infusion.

Alternately using a colonoscope, if the bleeding site can be visualized, it can be treated with cautery, epinephrine injection, or endoscopic clips.

Rarely reoperation with oversewing is required.

Leaks

The lowest leak rate is found after a small bowel or ileocolic anastomosis (1–3 %).

The highest leak rate is after a coloanal anastomosis (10–20 %). The incidence of leak is strongly associated with the distance of the anastomosis from the anal verge.

The ileal pouch-anal anastomosis has a leak rate of 5–10 %.

Immunosuppressive drug therapy (prednisone >40 mg/day and antitumor necrosis factor alpha agents) is a significant risk factor associated with an ileal pouch-anal anastomotic leak.

Role of Fecal Diversion

A proximal stoma minimizes the consequences of an anastomotic leak but does not reduce the actual incidence of a leak.

A proximal stoma may reduce the need for surgical intervention should a leak occur.

Table 10.2 lists indications when a diverting ileostomy should be considered.

Table 10.2

Indications for a diverting loop ileostomy

1. Coloanal or low colorectal anastomosis (<6 cm from anal verge)

2. Ileoanal anastomosis

3. Severe malnutrition

4. Significant immunosuppression (i.e., prednisone >40 mg/day, anti-TNF agents)

5. Hemodynamic instability

6. Excessive intraoperative blood loss

7. Purulent peritonitis

8. Pelvic sepsis

9. Neoadjuvant therapy

Patients with comorbidities who lack the “physiologic reserve” to tolerate an anastomotic leak should strongly be considered for proximal diversion even if other risk factors are not present.

Neoadjuvant radiation therapy in patients undergoing a low pelvic anastomosis for rectal cancer does not appear to increase the incidence of an anastomotic leak. However, surgeons tend to cover this anastomosis with a proximal stoma which may reduce the clinical manifestations of a leak.

Role of Pelvic Drains

The use of a drain to minimize the risk of an anastomotic leak is controversial, and the use of a drain has been shown to neither harm nor benefit an anastomosis.

One study did show the use of a drain reduced the incidence of clinical anastomotic leak after short-course neoadjuvant radiation therapy.

Diagnosis and Management of Anastomotic Leak

Free anastomotic leaks are leaks with fecal contents spread throughout the abdominal cavity.

Patients present with fever, tachycardia, hypotension, leukocytosis, and peritonitis.

Feculent fluid may egress via the surgical incision (or pelvic drain if present).

Radiological studies may localize the leak but should not delay reoperation.

Patients with a free leak should be taken to the operating room after fluid resuscitation and intravenous antibiotics are administered.

After a thorough washout, the treatment is dictated by the findings.

Most colorectal anastomosis will require anastomotic takedown and an end colostomy.

To minimize the effects of a friable rectal stump (that cannot be closed with staples or sutures nor brought to the skin surface as a mucous fistula), placement of transabdominal and transanal drains is indicated.

Selective small bowel or ileocolic anastomotic defects can be repaired. However, resection of the anastomosis with creation of a new anastomosis or stoma is the most conservative option.

Placement of the repaired anastomosis under the surgical incision will result in an enterocutaneous fistula instead of a second bout of peritonitis should a second leak occur.

Any concern regarding viability of the bowel ends necessitates takedown of the anastomosis and creation of a stoma.

Small defects in a colorectal anastomosis, in select circumstances, may be repaired and a proximal ileostomy created. This should be avoided when there is a large fecal load between the ileostomy and the repaired anastomosis.

Creation of a stoma in the setting of peritonitis can be challenging due to a thickened rigid mesentery. If difficulty exists in creating the conventional stoma, two options exist:

1.

A loop end stoma provides extra mesenteric length and better blood supply than a traditional end stoma.

2.

Bringing the stoma up to the skin through the upper aspect of the midline incision can sometimes be the only alternative. In some severe cases, the bowel can only be wrapped in gauze and matured 5–7 days later to ensure viability and avoid complete mucocutaneous separation and retraction.

A contained anastomotic leak is walled off and typically located in the pelvis presenting as an abscess.

If the abscess is small and contrast flows freely into the bowel, the patient can be treated with intravenous antibiotics, bowel rest, and observation.

Larger abscesses or those removed from the site of the anastomosis may require radiologically guided drainage.

A contained leak rarely requires immediate operative intervention, but surgery may eventually be required if the patient develops a cutaneous fistula, anastomotic stricture, or chronic presacral cavity.

Fistulae

Colocutaneous fistulas frequently close with conservative management (total parenteral nutrition or low residue diet and fistula pouching to protect the skin).

Many patients do not require IV nutrition and can eat a solid diet while being monitored for fistula closure.

After 3–6 months if the fistula persists, reoperation with reconstruction of the anastomosis can be performed.

Successful injection of fibrin glue has been reported as an alternative to reoperation.

Colovaginal fistula typically results from either an anastomotic leak that necessitates through the vaginal cuff (in a woman who has had a hysterectomy) or the inadvertent inclusion of the vaginal wall in the staple line. Spontaneous closure is rare in either of these circumstances.

Intolerable or copious vaginal drainage may require proximal diversion. Alternatively a daily large-volume enema to evacuate colonic contents may defer a stoma until repair is undertaken.

At 3–6 months reoperation can be performed. Options for repair include an advancement flap (colonic or vaginal), a rectal sleeve advancement flap, tissue interposition (labus majorum or gracilis), or laparotomy with a redo coloanal anastomosis.

Chronic presacral abscess or sinus may be seen after a leak from a coloanal/rectal or ileal pouch-anal anastomotic leak.

The presentation may be subtle with vague pelvic pain, fevers, increased stool frequency, urgency, or bleeding.

A pelvic CT usually shows presacral inflammation. A contrast enema demonstrates the posterior midline sinus extending from the anastomosis into the presacral space.

During an exam under anesthesia, a probe is placed in the posterior anastomotic defect, and the chronic cavity is laid open with cautery or the laparoscopic linear cutting stapler. Either process divides the luminal-cavity septum and allows free drainage and healing of the cavity by secondary intention.

An endoscopically placed vacuum-sponge device has been described as a method to close early and late presacral sinuses.

A redo coloanal anastomosis is considered for persistent sinuses after failure of other treatments.

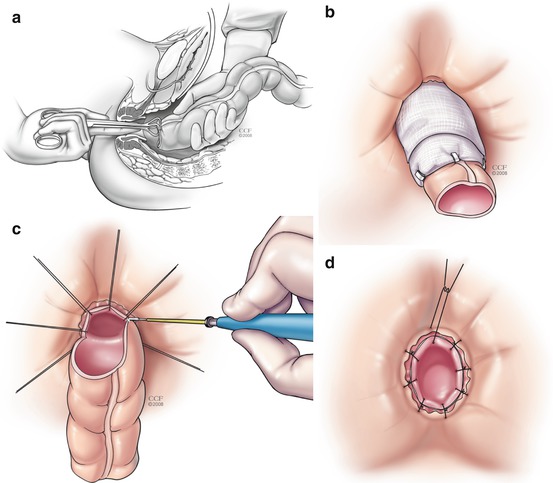

For redo coloanal anastomosis, the two-stage Turnbull-Cutait is a useful operation. During the first stage, the failed anastomosis is resected and the sepsis in the presacral space debrided. The descending colon is mobilized and brought out through the anal canal (Fig. 10.1a) and the exteriorized segment wrapped with gauze (Fig. 10.1b). After 5–10 days the patient returns to the operating room and the exteriorized segment is excised (Fig. 10.1c) and a delayed coloanal anastomosis is performed (Fig. 10.1d).

Fig. 10.1

(a–d) Turnbull-Cutait abdominoperineal pull-through procedure

Stricture

Anastomotic strictures can present 2–12 months after surgery with increasing constipation and difficulty evacuating.

Causes of anastomotic stricture include leak, ischemia, or, if initially done for malignancy—recurrent cancer.

For strictures after a cancer operation, recurrence must be excluded with a CT scan and positron emission tomography (PET) scan. For any mass or abnormality, biopsy is mandatory.

Low colorectal, coloanal, or ileal pouch-anal anastomosis may be successfully dilated with a finger or rubber dilators. Dilatation is more successful if initiated within the first few weeks after surgery.

Most coloanal and ileoanal anastomosis has some degree of stricture in the early postoperative period (particularly if a diverting stoma is present). Since most are soft, they can easily be dilated with an index finger. All these anastomosis should undergo digital examination 4–6 weeks after surgery or just before stoma closure (which occurs usually around 2–3 months after initial surgery).

Narrowed colorectal, colocolic, or ileocolic strictures may be treated with endoscopic balloon dilatation.

If these measure fail, or if the stricture is extremely tight or long, revisionary surgery may be required. These operations are difficult and in some cases permanent fecal diversion is the only option.

Genitourinary Complications

Ureteral Injuries

A ureter injury usually occurs at one of four specific points during pelvic dissection:

The first is high ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery between the upper and middle third of the left ureter. This is usually a transection injury and can be repaired primarily using an end-to-end repair over a stent.

The second is at the level of the sacral promontory; when mobilizing the upper mesorectum, the left ureter may be closely associated with the sigmoid colon or adherent to it. The injury may be tangential and not easily recognized, especially in the setting of a phlegmon or abscess. Ureteric stents help recognize an injury at this level but not prevent it. Injury at this level is managed by primary repair or ligation of the distal stump with creation of a ureteroneocystostomy with Boari flap or psoas hitch repair.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree