Apical Support Defects

Robert E. Gutman

INTRODUCTION

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is a common condition, with an estimated 225,964 surgical procedures performed in 1997, according to the National Hospital Discharge Survey (1). There is an 11% lifetime risk of surgery for prolapse and urinary incontinence, with a reoperation rate of about 30% (2). The annual cost for treating POP has been estimated to be $1 billion (3). Prolapse treatment options include observation without intervention, pessary fitting, or surgery, as previously discussed in Chapter 27. This chapter provides a comprehensive review of surgical management of apical support defects and a decision analysis for choosing an appropriate procedure.

Anatomical studies of vaginal support have demonstrated different levels of support, and POP in any given patient is usually a combination of support defects. The uterosacral and cardinal ligaments provide level I support of the vaginal apex; the lateral attachments of the endopelvic fascia and vagina to the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis contribute level II support of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls; and the perineal membrane and perineal body ensure level III support of the distal vagina and surrounding structures (urethrovesical junction and perineum) (4). The muscular integrity and neurological function of the levator ani also play a critical role in the support mechanism. Proper surgical correction requires identification of the anatomical defects, which can be present at the vaginal apex, rectovaginal fascia, and pubocervical fascia. Recent studies displayed a high correlation of apical descensus with anterior vaginal wall prolapse (5,6). While this seems relatively intuitive, it emphasizes the need for appropriate apical suspension to adequately correct anterior vaginal wall prolapse. Posterior vaginal wall prolapse may also be correlated with apical support, although the degree of correlation seems less than that of the anterior wall. Surgical repair frequently combines repairs of the anterior vaginal wall, posterior vaginal wall, and vaginal apex, depending on the specific support defects present. Consequently, proper identification of all support defects is essential, and correction of apical support is frequently the cornerstone of many prolapse surgeries.

Prolapse surgery should strive to alleviate symptoms related to pelvic support, restore normal anatomical relationships, optimize bladder, bowel, and coital function, and correct coexisting pelvic pathology using a durable repair with low morbidity. In choosing the best procedure for a patient, surgery should be individualized taking into account patient factors, surgeon factors, as well as patient preferences and expectations. Patient factors include those that potentially increase the risk of recurrent prolapse (prior prolapse surgery, severity of prolapse [7], young age [7], wide genital hiatus [8], levator weakness, and increased intra-abdominal pressures from occupation/recreation involving heavy lifting, continual cough from tobacco use, obesity, and chronic constipation) and those that may favor one approach over another due to morbidity and effect on vaginal dimensions (comorbid conditions, obesity, shortened vaginal length). Surgeon factors that influence selection of a specific procedure include the surgeon’s repertoire, specific surgical expertise, concomitant procedures planned (hysterectomy, incontinence surgery, cystocele repair, rectocele repair), and existing biases. These factors are all greatly influenced by residency and/or fellowship training.

SURGICAL PROCEDURES FOR APICAL SUPPORT

Apical support procedures can be divided into three groups: restorative procedures that use native support structures; compensatory procedures that add a graft for increased strength; and obliterative procedures that close the vaginal lumen. Sacral colpopexy

is the most commonly utilized compensatory repair. While typically performed through a laparotomy, it can also be accomplished laparoscopically. It is widely considered to be the most durable surgical procedure for anatomical support of the vaginal apex, with the lowest rate of recurrent vault prolapse (9, 10, 11, 12). There are several restorative procedures, which are usually vaginal repairs, including uterosacral ligament suspension, sacrospinous ligament fixation, iliococcygeus suspension, and McCall culdoplasty. Obliterative procedures such as the LeFort colpocleisis or total colpocleisis/colpectomy are less invasive and offer success rates similar to sacral colpopexy, with low complication rates. Although these are apical support procedures, they are covered in detail in Chapter 31. This chapter will concentrate on restorative and compensatory procedures that maintain vaginal integrity.

is the most commonly utilized compensatory repair. While typically performed through a laparotomy, it can also be accomplished laparoscopically. It is widely considered to be the most durable surgical procedure for anatomical support of the vaginal apex, with the lowest rate of recurrent vault prolapse (9, 10, 11, 12). There are several restorative procedures, which are usually vaginal repairs, including uterosacral ligament suspension, sacrospinous ligament fixation, iliococcygeus suspension, and McCall culdoplasty. Obliterative procedures such as the LeFort colpocleisis or total colpocleisis/colpectomy are less invasive and offer success rates similar to sacral colpopexy, with low complication rates. Although these are apical support procedures, they are covered in detail in Chapter 31. This chapter will concentrate on restorative and compensatory procedures that maintain vaginal integrity.

There is a wide variety of opinion regarding the optimal vaginal procedure, and there are no prospective comparative studies. There are retrospective and prospective trials comparing sacral colpopexy to sacrospinous ligament fixation, with conflicting results. Sacral colpopexy appears to have less recurrent apical prolapse, but there may be advantages of the vaginal approach such as decreased morbidity, less postoperative pain, and quicker return to activities of daily living. There may not be an advantage for either approach when considering symptomatic improvement or overall patient satisfaction. Alternatively, one approach may have benefits for certain patient populations. Therefore, surgeons must decipher the literature to determine the best approach for a particular patient. The choice of procedure also depends on the surgeon’s comfort with a procedure and his or her ability to perform a variety of different operations for apical prolapse.

The purpose of the following sections is to provide an in-depth analysis of the most commonly used restorative and compensatory repairs. Surgical technique will be discussed with specific attention paid to key steps in the procedures. Anatomical outcomes, symptomatic improvement, and complication rates will be reviewed based on the available literature. After this has been outlined for each individual surgery, the results of comparative studies, both prospective and retrospective, will be appraised.

Restorative Procedures

McCall Culdoplasty

Surgical Technique

McCall was the first to publish a technique known by many as the “New Orleans culdoplasty” that used the uterosacral ligaments for support and treatment of enterocele. While he named the technique the “posterior culdeplasty,” the technique became known as the McCall culdoplasty (13). Though described initially as a primary apical support procedure at the time of vaginal hysterectomy, many utilize the McCall culdoplasty prophylactically to prevent enteroceles. Apical descensus permitting vaginal hysterectomy suggests the need for an apical support procedure to prevent development of vaginal vault prolapse.

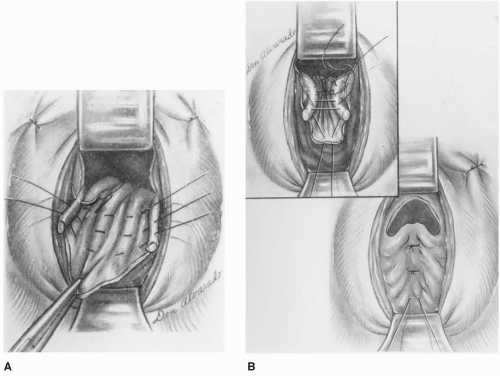

The McCall culdoplasty has been modified over the years, but the basic principles remain unchanged. McCall recommended placement of internal nonabsorbable sutures and external absorbable sutures. He advocated at least three internal nonabsorbable sutures, with the first suture placed approximately 2 cm above the cut edge of the uterosacral ligament. After stitching the uterosacral ligament, several bites of peritoneum overlying the rectum, including the redundant enterocele sac, are taken at 1- to 2-cm intervals until the contralateral uterosacral ligament is reached and stitched. While the ends of the first suture are held, additional internal sutures are placed proximal to the first. The number of internal sutures depends on the size of the enterocele. Next, the external absorbable sutures are placed just lateral to the midline, near the vaginal cuff, through the proximal posterior vaginal wall and peritoneum. The posteromedial aspect of the ipsilateral ligament is then sutured, followed by the contralateral ligament, and finally the suture exits the peritoneum and proximal posterior vaginal wall close to the cuff just lateral to the midline at the level of insertion. McCall recommended three external sutures, placed at intervals between the internal stitches, with the highest suture placed at the top of the newly supported vagina. Internal sutures are tied first, followed by external sutures, plicating the uterosacral ligaments to the posterior vaginal cuff and obliterating the cul-de-sac.

Modifications of this technique have subsequently been developed, including the Mayo, Mayo-McCall, modified, and high McCall culdoplasty. These variations differ with respect to the number of internal and external sutures, shortening of the uterosacral ligaments, and external sutures that incorporate the cul-de-sac peritoneum. When performing this procedure, we typically use one or two nonabsorbable internal sutures followed by a single absorbable external suture, all of which incorporate cul-de-sac peritoneum. The external McCall suture is normally tied after cuff closure by pushing the cuff cephalad toward the sacrum. Cuff closure can be considerably more challenging after these sutures have already been tied into place (Fig. 29.1).

Surgical Outcomes

McCall (13) reported on a series of 45 patients undergoing posterior culdeplasty. All but two procedures were done at the time of vaginal hysterectomy. Follow-up ranged from 3 months to 3 years, and there had been no known cases of recurrent enterocele formation or vault prolapse. The procedure was found to restore vaginal length without shortening.

Symmonds et al (14) evaluated the results of 180 patients undergoing a Mayo culdoplasty for grade III or IV vault prolapse. Successful repair based on anatomical assessment, and overall patient satisfaction was accomplished in 142 (89%) of the 160 patients available for follow-up between 1 and 12 years postoperatively. Nine (5.5%) women had “fair” results, all of whom had adequate apical support but required reoperation for recurrent anterior or posterior wall prolapse. Seven (4%) of the nine who had “poor” results required reoperation to obtain a “good” result. Among the other two patients with a “poor” result, one had recurrent vault prolapse and the other died postoperatively from a myocardial infarction. Other serious complications were rare.

Webb et al (15) reported on 660 women undergoing Mayo culdoplasty for primary repair of posthysterectomy vault prolapse. Subjective outcomes of mailed and telephone questionnaires revealed an absence of prolapse symptoms, overall satisfaction, and a low reoperation rate for the majority of respondents. Low intraoperative and perioperative complication rates were observed: 2.3% cystotomy or proctotomy repaired immediately without sequelae, 1.3% vault hematoma, 0.6% cuff cellulitis or abscess, and 2.2% blood transfusions.

Karram et al (16) performed a large retrospective case series of high uterosacral ligament suspension with plication, a similar but modified McCall culdoplasty. The uterosacral ligaments and intervening peritoneum were plicated with nonabsorbable sutures and the superior aspects of the pubocervical and rectovaginal fascia were then anchored to the ligaments on each side using delayed absorbable sutures. Of the 168 women available for follow-up, 150 (89%) were “happy” or “satisfied”

with their results at an average of 21.6 months. There were two (1%) apical recurrences and a 5.5% overall reoperation rate, with an additional 5% having at least grade 2 recurrent prolapse that was either asymptomatic or did not require further treatment. There was also one small bowel injury that required laparotomy and one postoperative ileus from a pelvic abscess that required delayed laparotomy, abscess draining, and colonic diversion.

with their results at an average of 21.6 months. There were two (1%) apical recurrences and a 5.5% overall reoperation rate, with an additional 5% having at least grade 2 recurrent prolapse that was either asymptomatic or did not require further treatment. There was also one small bowel injury that required laparotomy and one postoperative ileus from a pelvic abscess that required delayed laparotomy, abscess draining, and colonic diversion.

Colombo and Milani (17) retrospectively evaluated 62 women undergoing a modified McCall culdoplasty for grade 2 or 3 uterine prolapse using a series of three absorbable sutures. Over a median follow-up of 3 years, 15% had recurrent prolapse, but only 5% had recurrences that involved the vaginal apex. There were no major complications.

A major concern in surgeries that require suture placement through the uterosacral ligament is ureteral injury. McCall culdoplasty procedures have low rates of ureteral injury, ranging from 0% to 3%. Colombo (17) and Symmonds (14) did not observe any ureteral injuries in their series. This is in contrast to the larger Webb et al (15) series of 660, with four (0.6%) ureteral injuries: 1 patient developed a ureterovaginal fistula requiring ureteroneocystotomy; 1 injury resolved with observation; 1 patient required stent placement; and 1 patient needed laparotomy with removal of the modified McCall sutures. Most likely these four cases present only the symptomatic postoperative ureteral obstructions. The true ureteral injury rate may be higher with potentially asymptomatic undiagnosed cases in the absence of routine intraoperative cystoscopy. Using universal intraoperative cystoscopy, Karram et al (16) had five (3%) ureteral injuries: four involved ureteral kinking, which resolved after releasing the sutures, and one ureterotomy requiring ureteral reimplantation. Aronson et al (18) more recently reported only three (0.7%) ureteral injuries in 411 consecutive cases using intraoperative cystoscopy with intravenous indigo carmine, with only one (0.24%) attributable to a Mayo-McCall uterosacral ligament suspension.

While the above procedures document success rates for McCall culdoplasty as an apical support procedure, many consider it primarily for prevention and treatment of enteroceles. Cruikshank and Kovak (19) performed a randomized control trial comparing three different surgical treatments to prevent enterocele formation at the time of vaginal hysterectomy. At 3 years, the modified McCall culdoplasty had fewer stage I and stage II posterior superior vaginal segment (enterocele) recurrences (2/33 vs. 10/33 and 13/33 in the other two groups, p = 0.004). Thus, McCall culdoplasty is useful for prevention and treatment of enteroceles as well as apical support.

Uterosacral Ligament Suspension

Surgical Technique

The uterosacral ligaments have been utilized in vaginal reconstructions as early as 1927, when Miller (20) described bilateral suspension of the vaginal vault to the uterosacral ligaments. Techniques have evolved over time with modifications to the attachment sites, plication methods, and cul-de-sac closure. More recently there has been a trend to leave the uterosacral ligaments in a more physiologic position without midline plication. We believe this to be the major distinction between the McCall culdoplasty techniques listed above and uterosacral ligament suspensions.

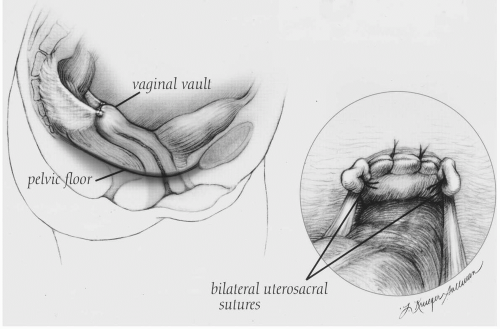

Following vaginal hysterectomy or posthysterectomy cuff colpotomy, the patient is placed in Trendelenburg position and the small bowel is packed away using a moistened 6-inch Kerlix sponge. Breisky-Navratil retractors help deflect the rectum medially and the bowel and surgical pack cephalad. The remnants of the distal uterosacral ligaments are identified and grasped. Caudal traction on the distal uterosacral ligament along with the use of a headlamp facilitates visualization of the fanlike projection toward the sacrum. The first nonabsorbable suture of at least 2-0 gauge is placed at the level of the ischial spine, with care taken to avoid locations within 1 cm of the anterior edge of the uterosacral ligament, where the ureter is more vulnerable. Traction on this first suture assists placement of a second more proximal suture approximately 1 cm craniosacral to the ischial spine. One end of each suture is then secured to the pubocervical fascia and anterior vaginal wall excluding the epithelium and the other to the rectovaginal fascia and posterior vaginal wall excluding the epithelium. If using two sutures on each side, the proximal uterosacral suture is placed approximately 1 cm medial to the distal uterosacral suture, which is secured near the angle of the vaginal cuff. Some authors have advocated placing up to three sutures on each side; however, we have concerns about increased risk of sacral trunk nerve injury (especially S2 and S3) with a third suture placed closer to the sacrum as well as with deep suture placement. An additional nonabsorbable mattress suture approximates the midline pubocervical and rectovaginal fascia, preventing enterocele formation. Next the sutures are tied into place and the long ends held until cystoscopy confirms ureteral patency. The sutures are then trimmed and the cuff is closed (Fig. 29.2). Stent

placement may be attempted in the absence of ureteral flow. Usually, release of the distal uterosacral suture alleviates the obstruction caused by kinking of the ureter. Direct ureteral injury requiring reimplantation is rare. Nevertheless, postoperative cystoscopy is essential for a safe repair.

placement may be attempted in the absence of ureteral flow. Usually, release of the distal uterosacral suture alleviates the obstruction caused by kinking of the ureter. Direct ureteral injury requiring reimplantation is rare. Nevertheless, postoperative cystoscopy is essential for a safe repair.

Buller et al (21) performed suture pullout studies on cadavers and concluded that the intermediate segment of the uterosacral ligament was the optimal site when balancing strength and safety in vaginal reconstruction. The ischial spine was found to be a good marker of this intermediate segment, which has good strength with fewer vital, subjacent structures, including vasculature and nerves. The course of the ureter and uterosacral ligament diverges with less tension transmitted to the ureter as we proceed from the cervical portion toward the sacrum.

This procedure can also be performed abdominally during laparotomy or laparoscopy. It may be useful for cases of mild vault laxity or as a temporary measure without hysterectomy for women with more severe uterine prolapse planning future childbearing. Although the operative technique is altered by the approach, the critical landmarks and uterosacral ligament suture location remain unchanged. Results from small case series with short-term follow-up indicate similar success for laparoscopic uterosacral hysteropexy (22,23).

Surgical Outcomes

Several retrospective case series report excellent subjective and objective outcomes ranging from 80% to 100% with low morbidity and mortality during uterosacral ligament suspension (24, 25, 26, 27). In the largest of these series, Shull et al (26) discovered a high objective success rate using the Baden-Walker halfway scoring system. Of the 302 consecutive cases, 289 (96%) patients returned for at least one follow-up visit and 251 (87%) had completely normal support. Recurrent prolapse at any site was found in 13%, but only 5% had grade 2 or more prolapse. There were no apical recurrences at the initial postoperative visit and only four (1%) apical recurrences up to 3 years postoperatively. The cuff and cul-de-sac displayed the most durable support, followed by the posterior compartment and then the anterior compartment. There were four (1%) ureteral injuries: two required removal and replacement of suspensory sutures, one sustained a needle-stick injury, and one required

ureteroneocystotomy for an injury occurring during multiple vaginal repairs of all compartments. Only three (1%) patients needed transfusions, and there was one death shortly after release from the hospital. Shull et al’s series did not address symptom resolution.

ureteroneocystotomy for an injury occurring during multiple vaginal repairs of all compartments. Only three (1%) patients needed transfusions, and there was one death shortly after release from the hospital. Shull et al’s series did not address symptom resolution.

Similarly, Jenkins (27) performed retrospective chart reviews on 50 women undergoing uterosacral ligament suspension focusing on anatomical outcomes. Initially he used permanent monofilament sutures but later changed to delayed absorbable sutures secondary to three cases of suture erosion. Follow-up ranged from 6 to 48 months, and there were no cases of recurrent apical prolapse. Two cystotomies occurred during entry in posthysterectomy patients, and there were no transfusions, ureteral injuries, or bowel injuries.

Several studies address subjective outcomes. Amundsen et al (24) retrospectively evaluated 33 patients undergoing uterosacral vault suspension with absorbable sutures at a mean follow-up of 28 months. Eighty-two percent of women had resolution of prolapse symptoms with overall support less than or equal to stage I on Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POPQ) examination. Recurrences were seen at the posterior wall in 12% and the apex in 6%. Vaginal length decreased by 0.9 cm, which was statistically but not clinically significant. The only complications consisted of one (3%) case of ureteral kinking, which resolved with suture removal, and one patient who required transfusion.

Wheeler et al (28) discovered similarly high patient satisfaction (84%) with apical support stage I or greater on POPQ examinations for women undergoing uterosacral suspension combined with cystocele repair augmented by porcine dermis graft. Unfortunately, there was a high rate of at least stage II recurrent anterior wall prolapse (50%).

Barber et al (25) retrospectively reported on 46 women at a mean follow-up of 15.5 months after uterosacral ligament vaginal vault suspension performed with permanent and delayed absorbable sutures. Symptomatic and anatomical improvement occurred in 90% of women, with two (5%) cases of recurrent stage III apical prolapse. Only 67% had anatomical support for all compartments less than or equal to stage I based on the POPQ system; however, apical support was better, with 82% at stage 0 and 13% at stage 1. This series had the highest rate of ureteral injury, seen in five (11%) subjects. Three resolved with suture removal and two required reimplantation. Other complications included one transfusion, one case of cuff cellulitis, and one myocardial infarction resulting in cardiogenic shock and death in a patient with known preoperative coronary artery disease. Vaginal shortening of 0.75 cm was observed, with 36/41 (88%) having a total vaginal length of at least 7 cm. Thus, uterosacral ligament suspension appears to consistently decrease the vaginal length approximately 1 cm and may not be appropriate in sexually active women with shortened vaginal length preoperatively.

It is difficult to clearly distinguish the uterosacral ligament suspensions described above from the high uterosacral ligament plications found in the McCall culdoplasty section. All use the proximal uterosacral ligaments for support, but they differ with respect to midline plication of these ligaments. The distinction becomes blurred when we consider that Jenkins and Barber performed separate McCall culdeplasty-like procedures with plication of the distal uterosacral ligaments in the majority of women to treat enteroceles. Rates of ureteral injuries were similar, with the exception of Barber’s study. We tend to avoid midline plication of the uterosacral ligaments, which results in a less physiologic repair; however, the impact of midline plication on vaginal length, vaginal caliber, and sexual function remains unclear.

More recently neuropathic pain has been associated with uterosacral ligament suspension. We believe that this is an underreported phenomenon that has been largely ignored and falsely attributed to surgical positioning. Based on recent anatomical evaluation, we consider this pain to result from entrapment of or direct injury to the sacral nerve roots, primarily S2 and S3, which are more vulnerable with deep suture placement at proximal uterosacral ligament sites closer to the sacrum (29,30). The majority of this pain is self-limited and will resolve over time, but there have been reported cases of rapid resolution with suture removal (31).

Iliococcygeus Suspension

Surgical Technique

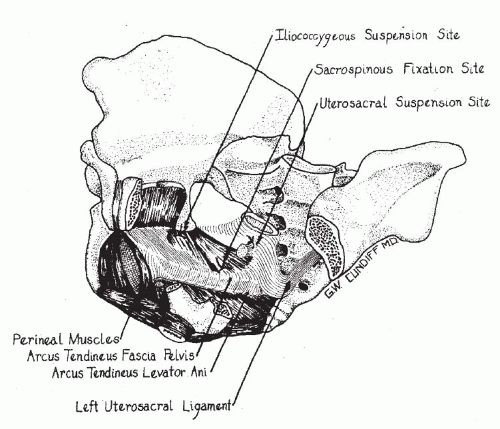

Originally described by Inmon in 1963 (32), this procedure is indicated for patients in whom the “uterosacral ligaments can not be identified or may be deemed insufficient to support the vaginal cuff.” This may also be performed when entry into the peritoneal cavity cannot be accomplished due to adhesions obliterating the cul-de-sac. Inmon described bilateral placement of a suture through the fascia overlying the iliococcygeus muscle just caudal to the ischial spine. The sutures are then anchored into the angles of the vaginal cuff, including the pubocervical and rectovaginal fascia. He emphasized the importance of reapproximating the superior aspects of the pubocervical fascia and rectovaginal

septum to prevent enterocele formation. Iliococcygeus suspension is infrequently necessary but provides a good option for vaginal reconstruction in the absence of adequate uterosacral ligaments. The vaginal axis is similar to uterosacral ligament suspension, and both are more physiologic than the extreme posterior deflection seen with sacrospinous ligament fixation. Due to the location of apical support, there is an inherent risk of vaginal shortening, which would be slightly worse than with uterosacral ligament suspension (Fig. 29.3).

septum to prevent enterocele formation. Iliococcygeus suspension is infrequently necessary but provides a good option for vaginal reconstruction in the absence of adequate uterosacral ligaments. The vaginal axis is similar to uterosacral ligament suspension, and both are more physiologic than the extreme posterior deflection seen with sacrospinous ligament fixation. Due to the location of apical support, there is an inherent risk of vaginal shortening, which would be slightly worse than with uterosacral ligament suspension (Fig. 29.3).

One advantage of this procedure is the avoidance of critical structures, thereby decreasing rates of nerve and ureteral injury that may occur during the other restorative surgeries. However, the nerve innervating the levator ani, which runs along the anterior surface of the muscle (33), could potentially be injured, as well as sacral nerves posterior to the iliococcygeus muscle, which may be damaged or entrapped with deep suture placement. The risk of sacral nerve root injury with iliococcygeus suspension should be lower than during uterosacral ligament suspension because suture placement is more caudal.

Surgical Outcomes

Inmon (32) performed the first three iliococcygeus suspension procedures between 1959 and 1961. At the time of the publication in 1963, all three patients had a well-supported vaginal cuff without “descensus on straining or coughing.” Since then there have been two larger case series. Shull et al (34) and Meeks et al (35) reported on 42 and 110 women respectively who had undergone iliococcygeus suspension with concomitant repairs. Thirteen (8%) of the 152 women developed recurrent prolapse. Only two (1%) prolapses recurred at the vaginal vault, while eight (5%) involved the anterior wall and three (2%) occurred at the posterior wall. All of Meeks’ subjects had at least 3 years of follow-up, while Shull’s ranged from 6 weeks to 5 years. In the larger series, there were two patients who required transfusion, one bowel injury, and one bladder injury, and 41/110 (37%) had a postoperative complication. Maher et al (36) retrospectively analyzed 36 women undergoing iliococcygeus suspension. At a mean follow-up of 21 months, subjective success was 91%, objective success was 53%, and overall patient satisfaction on a visual analog scale was 78 of 100. Eight percent had recurrent vault prolapse (at least grade II), 33% had recurrent cystocele, and 11% had recurrent rectocele. There was a surprisingly high rate of buttock pain and sciatica in 19% that resolved spontaneously within 3 months, and only one patient needed a transfusion. A more recent retrospective series evaluated 24 patients undergoing a combined modified McCall culdoplasty with an iliococcygeus suspension (37). They found one case of recurrent vault prolapse, one anterior vaginal wall prolapse, and one posterior vaginal wall prolapse over a mean follow-up of 24.4 months.

Sacrospinous Ligament Fixation

Surgical Technique

Sacrospinous ligament fixation was developed in Germany by Amreich and Richter in 1951 (38) and gained popularity in the United States through the work of Randall and Nichols (39,40). This vaginal

reconstructive surgery fixes the apex unilaterally or bilaterally to the sacrospinous ligament(s). The posterior vaginal wall is opened and the pararectal space is entered by penetrating the rectal pillar bluntly or sharply near the ischial spine. Straight retractors such as Breisky-Navratil retractors are inserted, deflecting the rectum medially and the bladder and ureter anteriorly. The course of the sacrospinous ligament is identified as the aponeurosis located within the substance of the coccygeus muscle running from the ischial spine toward the lower sacrum. One or two nonabsorbable sutures of at least 2-0 gauge are placed through the ligament 1.5 to 2 fingerbreadths medial to the ischial spine to avoid injury to the pudendal nerve and artery that pass just posterior to the ischial spine as they enter Alcock’s canal. Several devices have been developed to facilitate passage of the sutures through the ligament, including the Miya hook, Deschamps ligature carrier, Laurus needle driver, Nichols-Veronikis ligature carrier, and Shutt suture punch. The sutures are then anchored to the vaginal apex, including the superior aspect of the pubocervical and rectovaginal fascia. Most commonly a nonabsorbable suture excluding the vaginal epithelium is used with a pulley stitch; however, full-thickness vaginal wall delayed absorbable sutures have also been described. The sutures are then tied so that the apex of the vagina is approximated to the sacrospinous ligament without an intervening suture bridge. This procedure has also been described with uterine conservation for women wishing to preserve fertility.

reconstructive surgery fixes the apex unilaterally or bilaterally to the sacrospinous ligament(s). The posterior vaginal wall is opened and the pararectal space is entered by penetrating the rectal pillar bluntly or sharply near the ischial spine. Straight retractors such as Breisky-Navratil retractors are inserted, deflecting the rectum medially and the bladder and ureter anteriorly. The course of the sacrospinous ligament is identified as the aponeurosis located within the substance of the coccygeus muscle running from the ischial spine toward the lower sacrum. One or two nonabsorbable sutures of at least 2-0 gauge are placed through the ligament 1.5 to 2 fingerbreadths medial to the ischial spine to avoid injury to the pudendal nerve and artery that pass just posterior to the ischial spine as they enter Alcock’s canal. Several devices have been developed to facilitate passage of the sutures through the ligament, including the Miya hook, Deschamps ligature carrier, Laurus needle driver, Nichols-Veronikis ligature carrier, and Shutt suture punch. The sutures are then anchored to the vaginal apex, including the superior aspect of the pubocervical and rectovaginal fascia. Most commonly a nonabsorbable suture excluding the vaginal epithelium is used with a pulley stitch; however, full-thickness vaginal wall delayed absorbable sutures have also been described. The sutures are then tied so that the apex of the vagina is approximated to the sacrospinous ligament without an intervening suture bridge. This procedure has also been described with uterine conservation for women wishing to preserve fertility.

Surgical Outcomes

Sze and Karram reviewed 22 retrospective case series with 1,229 vault suspensions, of which 1,062 (86%) were available for follow-up. Duration of follow-up varied from 1 month to 11 years in 726 patients and unspecified duration in the remaining 336 subjects. There were 193 (18%) recurrences, including 81 (8%) at the anterior vaginal wall, 32 (3%) at the vault, 24 (2%) at the posterior wall, and 56 (5%) at unspecified or multiple sites. The severity of these recurrences was poorly documented and many did not require reoperation. Among the studies included in this review with over 80 subjects, success rates ranged between 65% and 97% (40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45). Most were objective outcomes alone; however, some involved combined objective and subjective measures, while others were unspecified. Serious complications rarely occurred, with the most common complication being hemorrhage. The transfusion rate was 2%, and three patients suffered life-threatening hemorrhages. There were only four cystotomies and five proctotomies, which were repaired immediately without further sequelae. Nerve injuries occurred in 4%, and 3% complained of gluteal pain that was localized to the side of the sacrospinous suture. There was one death from coronary thrombosis and another from vaginal evisceration. Only a handful of studies evaluated sexual function, discovering a small percentage of vaginal shortening, vaginal stenosis, and apareunia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree