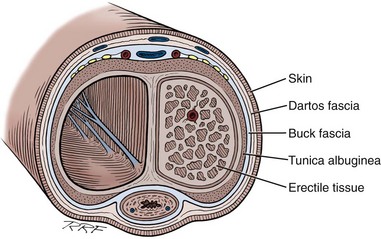

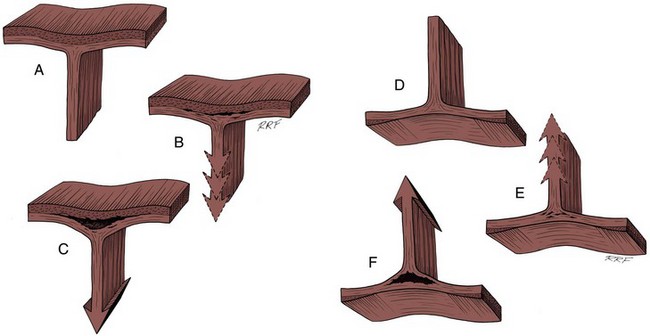

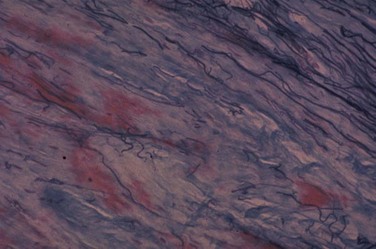

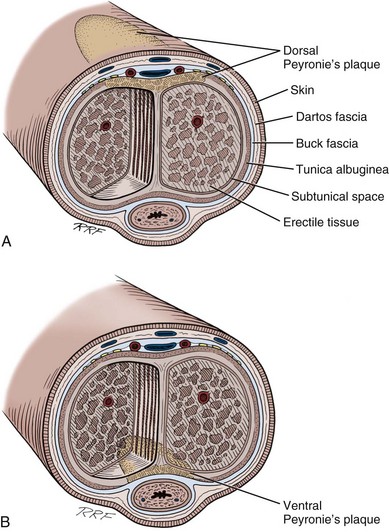

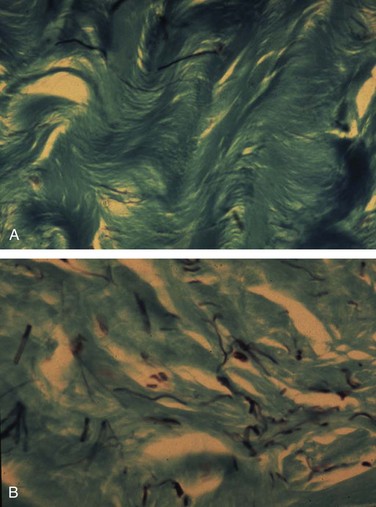

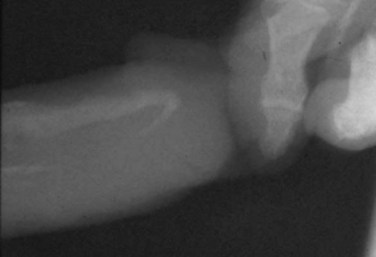

Gerald H. Jordan, MD, FACS, FAAP (Hon), FRCS (Hon), Kurt A. McCammon, MD, FACS Credit for the first description of Peyronie’s disease is given to François Gigot de la Peyronie in 1743 (Peyronie, 1743). Fallopius, however, first reported the entity in 1561. Peyronie’ (Peyronie, 1743). Fallopius, however, first reported the entity in 1561. Peyronie’s disease is also known as induratio plastica of the penis. In most patients, reassurance is sufficient and a necessity. For others, medical therapy is useful. Fortunately, only a minority of patients will have deformity that precludes them from having intercourse. Most of the patients with Peyronie’s disease do not require surgery. Surgery, at best, can be viewed as palliation for the mechanical effects of Peyronie’s disease and erectile dysfunction. The literature associates Peyronie’s disease with many entities. Some have stood the test of time; in others, the association has not. In a study by Nyberg and colleagues (1982), Peyronie’s disease was associated with Dupuytren disease. Dupuytren disease has a familial pattern known to be transmitted in an autosomal dominant pattern. Thirty percent to 40% of men with Peyronie’s disease will also have Dupuytren disease (Nyberg et al, 1982; Ralph et al, 1997). Other associated fibrotic conditions are contracture of the plantar fascia (Ledderhose disease) and tympanosclerosis. Peyronie’s disease is also reported to occur in patients after external trauma to the penis (e.g., seat belt injuries). To the authors’ knowledge, no reported incidence rate appears in the literature for such patients. However, all urologists who see any volume of patients with Peyronie’s disease will inevitably encounter one or two such patients a year who can attribute the onset of Peyronie’s disease only to an incident of external trauma to the penis. The relationship of Peyronie’s disease to diabetes mellitus likewise remains unclear. Certainly if one accepts the notion that erectile dysfunction can be an inciting event for the development of Peyronie’s disease, the relationship with diabetes mellitus will follow. To date, however, the incidence of Peyronie’s disease as associated with diabetes mellitus has not been defined, although patients with diabetes mellitus were shown to have statistically significant more curvature and worse vascular status compared with patients without diabetes mellitus (Kendirci et al, 2007; El-Sakka and Tayeb, 2009). The relationship to gout can only be regarded as anecdotal. The relationship with Paget disease of the bone, however, was noted in a nicely done study reported by Lyles (1997) in which patients with Paget disease were noted to have Peyronie’s disease at an incidence rate higher than that quoted for the population in general. Certain human leukocyte antigen subtypes have been incriminated as being causally related to the development of Peyronie’s disease. However, for a subtype to be positively linked to the development of Peyronie’s disease, a study of many thousands of patients would be required. Nyberg and associates, in 1982, Leffell, in 1997, and Ralph and colleagues, in 1997, suggested an association. The use of β-adrenergic blockers has been causally incriminated with regard to the development of Peyronie’s disease. However, the association was made when first-generation β blockers had just been released to the market. Like diabetes mellitus, those first-generation β blockers were also causally associated with erectile dysfunction. Thus, as possibly the case with diabetes mellitus and hypertension, the same relationship could hold true for the relationship to β blockers. Further study substantiating the relationship to diabetes exists (Lindsay et al, 1991; Kendirci et al, 2007; El-Sakka and Tayeb, 2009). Urethral instrumentation has been implicated as a cause of Peyronie’s disease. Any urologist who sees a large volume of patients with Peyronie’s disease will encounter, on a one or two per year basis, patients who had straight erections before transurethral surgery but with the resumption of intercourse after surgery noted curvature. Most of these patients do not complain of ventral curvature. This association should not be confused with Kelami syndrome, which is fibrosis of the corpus spongiosum so severe that it limits expansion of the ventral corpora cavernosa. Again, to the authors’ knowledge, no incidence figures exist for the relationship to urethral instrumentation (Carrieri et al, 1998). The symptomatic incidence of Peyronie’s disease has been estimated at 1%. In white men the average age at onset of Peyronie’s disease is 53 years. The asymptomatic prevalence is estimated at 0.4% to 1.0%. In a study of 100 men without known Peyronie’s disease, at autopsy 22 were found to have fibrotic lesions of the tunica albuginea compatible with Peyronie’s disease (Smith, 1969; Gelbard et al, 1990; Lindsay et al, 1991; Carson et al, 1999;Greenfield and Levine, 2005). Clearly, many think that the clinical incidence of Peyronie’s disease is increasing. The increase, however, may be associated with, and seems to coincide with, the increased use of erection-enhancing medications. The phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitor medications and the approved intracavernosal injection agents are not indicated for Peyronie’s disease. That does not mean that they are contraindicated but that during the final phase studies reviewed for drug approval that patients with Peyronie’s disease were excluded. To the authors’ knowledge there has never been any suggestion that PDE5 inhibitors are in any way directly causally related to the development of Peyronie’s disease nor is there suggestion that their use would worsen the course of Peyronie’s disease (Jalkut et al, 2003). Data are emerging to suggest that certain endothelial impairment may be reversed with the initiation of PDE5 inhibitor therapy. However, the concept of “endothelial rehabilitation” with PDE inhibitor therapy should be considered as suggested only (Rosano et al, 2005). Rajfer’s work suggests the opposite. PDE5 therapy or therapy with other promoters of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) (pentoxifylline) actually suggests that in the animal model cGMP functions as an antifibrotic and thus PDE5 medication and pentoxifylline therapy may actually counter the fibrotic process. Likewise, it is the authors’ belief that the scarring seen with intracavernosal injection therapy is related not to the medications necessarily but rather to the injection technique. There are certainly patients who can recall a given event in which they used their injection medication. The injection was accompanied by undue pain, a good erection was not achieved, and the patient then noticed an area of induration in the penis. After that, patients often notice deformity of the penis. Also, it could be theorized that the repetitive trauma of the needle may initiate a “Peyronie’s-like process.” The prolonged use of papaverine and phentolamine (Regitine) has been implicated as a cause of intracorporeal fibrosis, which is different from the fibrotic process of the tunica albuginea that is recognized as Peyronie’s disease. Key Points Epidemiology In examining the etiology of Peyronie’s disease it is important to review some facts concerning the anatomy of the corpora cavernosa (Fig. 28–1). The tunica albuginea is bilaminar throughout most of its circumference. It is composed of an outer longitudinal layer and an inner circular layer. The corpora are separated by an incompetent septum. In the pendulous portion of the penis there are intracavernous supporting fibers that anchor the inner layer of the corpora cavernosa at the 2-o’clock and 6-o’clock positions. The tunica albuginea varies in thickness from 1.5 to 3.0 mm, depending on the position on the circumference. The outer longitudinal layer attenuates in the ventral midline, and thus the tunica is monolaminar at that point. The outer longitudinal layer is thickest on the ventrum adjacent to the corpus spongiosum and on the dorsum and thinnest on the lateral aspects (El-Sakka et al, 1998b). Most patients with Peyronie’s disease demonstrate lesions dorsally. Because the tunica albuginea is bilaminar on the dorsum it is possible that these layers might delaminate with buckling trauma. Also, on the ventrum, the longitudinal layer is absent, thus potentially allowing dorsal buckling more easily (Devine and Horton, 1988; Border and Ruoslahti, 1992; Brock et al, 1997; Devine et al, 1997; Jarow and Lowe, 1997). The authors, as have others, note that in the case of calcified plaques the calcification seems to involve the inner circular lamina and, in fact, can be removed, leaving the outer lamina intact. The outer lamina is not normally compliant, but the predilection for calcification of the inner lamina calls to question the preciseness of the typical delamination hypothesis. Somers and Dawson (1997), in studies, have shown that Peyronie’s disease most likely begins with buckling trauma that causes injury to the septal insertion of the tunica albuginea. Intravasation of blood occurs with activation of fibrinogen (Fig. 28–2). The body responds to the effects of trauma; and macrophages, as well as neutrophils and mast cells, migrate to the area. Platelets are present because of the intravasation of blood, and fibrin becomes incarcerated in the healing process. Platelets, neutrophils, and mast cells secrete cytokines, autacoids, and vasoactive factors, many of which become involved in fibrosis. Platelets release serotonin and platelet-derived growth factors as well as transforming growth factors. The formation of thrombus leads to the deposition of fibronectin, which binds a number of growth factors, keeping them localized to the area of injury. Fibrinogen leakage leads to the deposition and incarceration of fibrin (Fig. 28–3). It has been proposed that the avascular nature of the tunica albuginea may impede clearance of many of these growth factors. The transforming growth factors, particularly transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), are capable of autoinducement. Thus, the accumulation of TGF-β1 is capable of inducement of further accumulation. The presence of TGF-β stimulating further release of TGF-β1 could possibly lead to an ongoing, smoldering, inflammatory process ending with disordered healing. There is good reason to suspect TGF-β1 as possibly involved with the formation of Peyronie’s plaque because it has been implicated in a number of soft tissue fibroses as well as with erectile dysfunction (Border and Ruoslahti, 1992; Border and Noble, 1994; Davis, 1997; Diegelmann, 1997; Van De Water, 1997; Moreland, 1998; Mulhall et al, 2001b). TGF-β1 is synthesized as a latent peptide by many cells; those pertinent to this discussion are platelets, macrophages, and fibroblasts. On activation, TGF-β1 binds to cell surface receptors and eventually results in synthesis of connective tissues with inhibition of collagenase (El-Sakka et al, 1997a, 1997b, 1998a). Also noted was that the expression and activity of Smad transcription factors of the TGF-β pathway is increased in fibroblasts of patients with Peyronie’s disease. The net result of this trauma with disordered healing is the formation of plaques that appear as scars and impede expansion of the tunica albuginea during erection, which results in curvature, and/or indentation, and/or foreshortening (Fig. 28–4). On histologic examination there is aberrant cicatrization with nonpolarization of collagen and diminished and erratic distribution of the elastin fibers (Fig. 28–5). Recent work at the University of California, San Francisco, has examined the role of matrix metalloproteinase in this abnormal scarring process. Matrix metalloproteinases are enzymes that are involved in the remodeling of extracellular matrix proteins. These remodeling enzymes are regulated by tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase. Failure or downregulation of matrix metalloproteinase has been implicated in a number of disease processes. In the case of Peyronie’s disease, if matrix metalloproteinases are downregulated that could function as a possible mechanism for the scarring process in Peyronie’s disease. In the studies, image analyses were used to examine the cavernosal tissues of Peyronie’s disease patients compared with control subjects having only prosthetic placement for other reasons. Those analyses showed a higher expression of the tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase in all of the components of the Peyronie’s plaques compared with the control subjects. Thus, inhibition of antiscarring enzymes can perhaps represent another facet of the etiology of the lesion that is recognized as the Peyronie’s plaque (Grazziotin et al, 2004). In a similar vane, Hauck and coworkers (2004) examined the role of α1-antitrypsin, which is a proteinase inhibitor, as a possible factor in the development of Peyronie’s disease. Reduction in α1-antitrypsin levels could result in a change in collagen metabolism. Previous work had suggested diminished levels, and such diminished levels could be associated with diminished tissue degradation (remodeling) and hence increased cicatrization. Hauck and coworkers did find diminished α1-antitrypsin levels in patients with Peyronie’s disease; however, compared with age-matched controls the levels were not diminished in Peyronie’s disease with regard to the control subjects. Thus α1-antitrypsin levels may vary with age but the association with Peyronie’s disease was not made. Studies also demonstrate the role of oxidative stress in addition to cytokine release in the development of Peyronie’s disease plaques. Acting as profibrotic factors, they interact with antifibrotic defense mechanisms, which, as already mentioned, may be inhibited. Oxidative stress intensifies in the fibroblasts of human Peyronie’s disease plaques and rat-modeled fibrosis (Ferrini et al, 2002; Vernet et al, 2002; Valente et al, 2003). Reactive oxygen species trigger profibrotic processes in a number of disease processes (Becker et al, 2001; Intengan et al, 2001). There is interplay between a number of mechanisms as they relate to fibrosis. Possibly of particular importance as previously mentioned is cGMP, one of the mediators of penile erection. cGMP has been found to be antifibrotic in Peyronie’s disease plaques. Long-term administration of PDE5 inhibitors prevents plaque formation in rat fibrosis models. PDE5 is expressed in tunical and Peyronie’s disease fibroblasts (Valente et al, 2003). Thus, as previously mentioned, the use of PDE5 inhibitors and cGMP promoters in patients with Peyronie’s disease may be helpful in a number of ways. Key Points Etiologic Factors Basic science research into the etiology of Peyronie’s disease is limited by the failure, to date, to develop a true reliable animal model of Peyronie’s disease. A couple of animal models have examined the injection of cytomodulin, a TGF-β promoter, and the injection of blood. Clearly, in both models, fibrotic lesions were produced. Whether these represent true models of Peyronie’s disease remains to be proved or disproved. These models of fibrosis, however, have led to interesting research regarding the pathogenesis of Peyronie’s disease. In addition, a number of cell culture models have been proposed and have allowed significant enlightenment with regard to cell cycle regulators and gene expression. The obvious comment about these models is that, of course, these do enlighten us with regard to the essential cell aberrations; however, most probably fail to truly represent what would be the in-vivo condition. They do allow, however, investigation with regard to agents that potentially can manipulate the behavior of the individual cell (El-Sakka et al, 1999; Perinchery et al, 2000; Bivalacqua et al, 2001; Mulhall et al, 2001a; Ferrini et al, 2002; Gonzalez-Cadavid et al, 2002; Lin et al, 2002; Magee et al, 2002; Hauck et al, 2003b; Kim et al, 2004; Piao et al, 2008). Several studies have examined the natural history of Peyronie’s disease (Hellstrom, 2003). In most cases there are two phases. The first is an active phase, which not uncommonly is associated with painful erections and changing deformity of the penis. This is followed by a quiescent secondary phase, which is characterized by stabilization of the deformity, with disappearance of painful erections, if they were present, and, in general, stability of the process. Up to a third of patients, however, present with what appears to be sudden development of painless deformity. It has been said that Peyronie’s disease totally resolves in some patients, but this is probably a misstatement. Clearly there are some patients who traumatize their penises and then develop curvature secondary to the inflammatory process and its associated loss of compliance. In some, the inflammation resolves without seeming to enter into the phase of smoldering inflammation that ends in disordered healing and scar formation. Thus the process is resolved. Semantically, however, these patients probably cannot be said to have resolved Peyronie’s disease; rather, the trauma has resolved without the development of Peyronie’s disease. In Mulhall’s study of men diagnosed promptly after development of Peyronie’s disease symptoms and findings who elected to avoid all therapy, few were found to show much improvement in curvature during a period of 12 months (O’Brien et al, 2004). Obviously this study could be faulted for not having observed the patients longer, but the point is made that “spontaneous resolution” of Peyronie’s disease is an infrequent occurrence. When the urologist is confronted with a patient with Peyronie’s disease it is imperative that he or she understand the mindset of that patient and indeed of the couple. It has been shown that couples in which the man has Peyronie’s disease, compared with age-matched adult couples, seem to engage in more frequent and more vigorous intercourse and often use positions that are potentially traumatic to the penis. These couples seem to relate by intercourse. It could be stated that Peyronie’s disease is a disease of aging tissue in a patient with a youthful libido (Williams and Thomas, 1970; Gelbard et al, 1990; Carson et al, 1999; Rosen et al, 2008). An association to trauma and position of intercourse has been proposed for some time, based on the assumption that certain positions of intercourse can be traumatic to the penis. However, this premise has not been well verified. The hypothesis is that patients with Peyronie’s disease have a higher incidence of penile trauma associated with intercourse (Jarow, 1997; Zargooshi, 2004). It has also been proposed that patients with Peyronie’s disease use positions of intercourse that are different and varied compared with a “control population” and may have less firm erections than a “control population,” therefore creating a situation in which intercourse could traumatize the penis. A study at the Eastern Virginia Medical School examined these hypotheses. Control subjects and Peyronie’s disease patients were aged matched. Peyronie’s disease patients had a higher incidence of Dupuytren disease as well as Ledderhose disease. It was found that patients with Peyronie’s disease reported traumatic intercourse in a much higher rate than control subjects, and this was highly statistically significant. However, compared with the control population in this study, Peyronie’s disease patients seemed to have firmer erections. When positions of intercourse were looked at, with the female superior position being believed to be potentially traumatic, Peyronie’s patients and control patients used different positions of intercourse at almost an identical rate. Further studies are obviously required (Logan et al, 2008). The relationship of erectile dysfunction with Peyronie’s disease is a difficult one to ascertain. Mention of erectile dysfunction after surgery begins with the first report of surgery for Peyronie’s disease (Lowsley and Boyce, 1950) using excision and grafting. In that series, erectile dysfunction postoperatively was a major source of failure. Interestingly, patients with ventral curvature were singled out as particularly at risk for postoperative problems with erectile dysfunction. The poor prognosis for that group of patients seems to persist into current series. Returning to articles concerning the natural history (Williams and Thomas, 1970; Gelbard et al, 1990), erectile dysfunction again is prominently mentioned. In Gelbard and colleagues’ manuscript (1990), a large number of patients discussed poor erections and erectile dysfunction. In the authors’ experience, erectile dysfunction precedes the onset of Peyronie’s disease in many patients. In an analysis in 1993 (Jordan and Angermeier, 1993) it was clear that erectile dysfunction is a significant factor in patients examined preoperatively. A review by Mulhall further clarifies the association of erectile dysfunction with Peyronie’s disease (Palese et al, 2004). In that analysis a large cohort of men were questioned with the International Index of Erectile Function, Erectile Function domain (IIEF/EF). The data showed that one third of men with Peyronie’s disease presented with erectile dysfunction at the time that they presented with Peyronie’s disease. Furthermore, a significant percentage of them had erectile dysfunction that preceded their notice of the onset of Peyronie’s disease and its diagnosis. The investigators also examined patients with dynamic infusion cavernosometry and cavernosography and found that venous leak is seen more commonly in men who develop erectile dysfunction with Peyronie’s disease; however, site-specific venous leak was not noted. There also was the confusing factor of those men with normal vascular parameters who by questionnaire had erectile dysfunction. This further emphasizes the strong psychological component seen in these patients and also the role of destabilization of rigidity by curvature and indentation. Since Brock and Lue’s analysis (1993) there are now a number of reports that have attempted to stratify patients preoperatively with functional testing. In those articles there is wide variance of opinion concerning the coexistence of erectile dysfunction with Peyronie’s disease. Jordan and Angermeier (1993) showed erectile dysfunction in almost 100% of patients; Jarow and Lowe (1997) showed that 76 of 95 patients were impotent by testing; and Ralph and coworkers (1992) showed that of 20 patients with erectile dysfunction who were studied with duplex ultrasonography, 90% had complaints of erectile dysfunction because of functional, not organic, causes. In Mulhall’s study cited earlier, by IIEF/EF criteria, 30% of that cohort had erectile dysfunction associated with Peyronie’s disease (Palese et al, 2004). Hellstrom’s analysis of more than 500 men, all evaluated with duplex ultrasonography, showed a significant relationship between the type of penile deformity and penile hemodynamics. The study showed that patients with hourglass deformity most commonly had arterial insufficiency. Veno-occlusive dysfunction was most prevalent in patients with ventral curvature. This fact makes Lowsley’s final statement in his 1950 paper almost prophetic: “Patients with ventral curvature do not do well with graft operations.” However, Hellstrom’s study did not demonstrate any statistical relationship between the type of deformity and the frequency of erectile dysfunction. All patients were evaluated with the IIEF/EF questionnaire (Kendirci et al, 2005). Thus what is in the literature is not clear other than the fact that patients preoperatively complain in large numbers of the psychological impact of their Peyronie’s disease and that those psychological aspects continue to plague good surgical results (Jones, 1997). On the basis of a study still to be published, men with and without Peyronie’s disease participated in a series of focus groups that were conducted in several cities. Most men indicated that the impact Peyronie’s disease has had on their life has been severe (Rosen et al, 2008). The emotions expressed by many of the men who were interviewed ranged from anger to frustration to hopelessness. Although many men—even those not in a steady relationship—were still having sex, most of those who were still having sex said that it was different from what it used to be and many were concerned that their condition would worsen and that they would not be able to have sexual intercourse in the future. In every focus group, most men said they had become resigned to the fact that there was nothing that could be done. Additional work is being done to develop a questionnaire to measure the impact of Peyronie’s disease on various aspects of a man’s life (Rosen et al, 2008). Jones (1997) deals best with the counseling issues of men with sexual dysfunction resulting from Peyronie’s disease. His comments are based on interviews of more than 1500 men with Peyronie’s disease. He describes counseling a patient with Peyronie’s disease as being much the same as counseling a person who has suffered a death and is grieving. As with death, grieving is complicated by denial, ambivalence, anxiety, depression, shame, embarrassment, and, in the case of this particular group of patients, self-disgust. Most of these patients are not good talkers. Jones (1997) suggests that these patients tend not to like to talk about their problems with their spouses and initially spurn counseling in many instances. A major point made by Jones (1997) in dealing with patients with Peyronie’s disease is that to avoid or to limit emotional factors patients and their partners need to hear the suggestion that they must “keep sexual expression alive, be active to whatever degree possible at every stage of the progression or regression of their Peyronie’s disease course.” Patients’ understanding of Peyronie’s disease is made worse many times by the comments of urologists and primary care physicians, who in general do not understand the disease. Many patients have been told that Peyronie’s disease is probably the end of their sex life. Many of these couples have related by the belief that “sex is intercourse.” Thus, when coitus is precluded, they avoid all sexual activity. Most men with Peyronie’s disease have ignored, at one point, the plea of their partners who have asked for intimacy regardless of whether there was intercourse. As mentioned, the relationship of the functional aspects to the organic aspects remains elusive. To define these aspects there must be uniformity in history-taking; there must be uniformity in preoperative assessment with regard to erectile function; and, in failures, there must be uniformity in postoperative assessment with regard to erectile dysfunction. Key Points Pathophysiology and Natural History The presenting symptoms of Peyronie’s disease include, in many patients, penile pain with erection; penile deformity, both flaccid and erect; shortening with and without an erection; plaque or indurated areas in the penis; and, in many patients, erectile dysfunction. On physical examination, virtually all patients have either a well-defined plaque or an area of induration that is palpable. The plaque is usually on the dorsal surface of the penis, intimately associated with the insertion of the septal fibers. Patients not uncommonly can remain sexually active with significant dorsal curvature (up to 45 degrees). Patients with lateral components or ventral Peyronie’s disease tolerate the deformity far less well. Mulhall’s analysis of the natural history of Peyronie’s disease in a group of men who avoided treatment but were observed carefully documents the frequent occurrence of penile shortening in this population (O’Brien et al, 2004). An interesting variant of Peyronie’s disease has been reported by Brock, who has coined the term septal-only Peyronie’s disease. In his description (cited in Bella, 2007), patients had nonpalpable scarring of the penile septum that caused deformity of the erect penis. In the authors’ experience there is palpable scarring; however, the scarring appears to be in the substance of the corpora cavernosa as opposed to the tunica albuginea associated with the insertion as is usually seen. In septal-only disease, the authors have found it difficult to tell whether the scarring is indeed Peyronie’s disease or perhaps a Peyronie’s lookalike. Fortunately, tumors of the erectile tissue of the corpora cavernosa are quite rare, but it is the authors’ practice to evaluate these patients with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Pain may be persistent in the inflammatory stage of the disease; it is usually not severe, but it can interfere with sexual function. Some patients also complain of being awakened in the morning or at night with pain during erection. Spontaneous improvement in pain virtually always occurs as the inflammation resolves. A small group of patients with extensive disease will have “circumferential plaques” and an unstable penis owing to the resulting hinge effect. Most patients complain of distal flaccidity. In dynamic infusion cavernosometry and cavernosography it was found, however, that the pressures were equal proximal and distal to the plaque (Jordan and Angermeier, 1993). Opinions vary with regard to the cause of distal tip flaccidity; one ultrasound study seemingly showed cavernosal fibrosis that ostensibly could interfere with distal perfusion of the corpus cavernosum (Ralph et al, 1992). However, in the authors’ experience, the fibrotic process is limited to the tunica albuginea, although the process can clearly involve the septal fibers and thicken them appreciably. Thus there is no corroboration of the finding of diffuse cavernosal fibrosis when these patients are taken to the operating room (Ralph et al, 1996). When the urologist is confronted with the patient with Peyronie’s disease the medical history should include the mode of onset (sudden vs. gradual) and time at onset. The course of disease is helpful with regard to determining the phase the patient is in. The history is obtained of prior penile surgery, urethral instrumentation or external trauma, medication or drug abuse, and fibromatosis including Dupuytren disease and Ledderhose disease. Family history of the other fibromatoses is revealing. Because most patients with Peyronie’s disease have an element or at least the aura of erectile dysfunction, risk factors for erectile dysfunction should also be assessed. The recent literature suggests that erectile dysfunction may be a sensitive hallmark of many vasculopathic conditions. Endothelial dysfunction is an important abnormality contributing to a decrease in penile vascular responses to sexual stimuli. Vascular disease has been shown to be the most common cause of erectile dysfunction. Cardiovascular disease and erectile dysfunction share a host of risk factors, including age, smoking, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus. Furthermore, the severity of coronary artery disease has been shown to correlate with the severity of erectile dysfunction (Feldman et al, 1994; Greenstein et al, 1997; Lue, 2000; Martin-Morales et al, 2001; Roumeguere et al, 2003). Thus, in addition to trying to glean factors from the patient about smoking, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and other suggestions of vascular disease, the inquiries must also extend to the patient’s family with regard to those same issues. Likewise, because a few of these patients will require surgery, the surgeon must carefully assess the need for screening with regard to a patient’s total vascular health. Imaging of the plaque is important for one purpose only, that is, the demonstration of calcification. Imaging to record plaque size is probably as useful as measuring plaque size and recording it on a diagram. Demonstration of calcification is easily accomplished with ultrasound examination. The calcified plaque will be shown as shadowed areas (Fig. 28–6). The plaque itself will be prominently imaged (Altaffer and Jordan, 1981; Balconi et al, 1988; Hauck et al, 2003a). Plain radiography is also equally effective in demonstrating calcification within the plaque (Fig. 28–7). The authors use a high-definition film (Kodak X-Omat ready-pack 8 × 10). This is accurate in imaging the calcification and allows minimal radiation exposure (20 mA at 49 kV). The testes are shielded with a lead sheet. Zero radiography is an effective way of demonstrating the plaque; however, the technology is not readily available with the increase in other imaging modalities. Computed tomography has no place in the examination of the penis for Peyronie’s disease. However, MRI, which does not effectively demonstrate plaque calcification, does image the plaque well. There is not universal agreement about the use of MRI for imaging of the plaque (Helweg et al, 1992; Vosshenrich et al, 1995; Andresen et al, 1998; Hauck et al, 2003a; Moncada, 2003; Perovic, 2003). In the authors’ opinion, at present, MRI evaluation is probably excessive; however, for the purposes of assessing the results of clinical trials MRI may have a place. The place of vascular testing is not clearly defined. Currently the use of vascular testing is variable. Some centers perform duplex ultrasound testing on all patients with Peyronie’s disease; other centers do not perform vascular testing at all, despite that patients are routinely operated on for Peyronie’s disease and, in some cases, receive prostheses as the primary treatment option (Kendirci et al, 2004, 2005; Pak et al, 2004

Anatomic Considerations and Etiologic Factors

Pathophysiology and Natural History

Symptoms

Evaluation of the Patient

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Peyronie’s Disease

• Peyronie’s disease presents as a variety of deformities of the penis. The symptomatic incidence has been estimated at 1%, but most think that the incidence is increasing and now can be conservatively estimated at 4% to 5%. Fortunately, most patients do not require surgery. Most do require reassurance and education. Surgery for Peyronie’s disease is considered palliation for the mechanical effects of the disease.

• Buckling trauma of the penis, usually occurring during intercourse, has been implicated in the development of Peyronie’s disease. TGF-β has been found to be related to the disordered healing process that leads to the scarring of the Peyronie’s plaque. In addition, failure of downregulation of a number of “antifibrotic” factors has been implicated.

• Studies that examine the natural history of Peyronie’s disease show that Peyronie’s disease presents usually as two phases. The first is an active phase; the second is a quiescent phase. Thus studies to evaluate the efficacy of pharmacotherapy are difficult; when the disease process enters the quiescent phase, many things noted during the acute phase disappear or become less apparent.