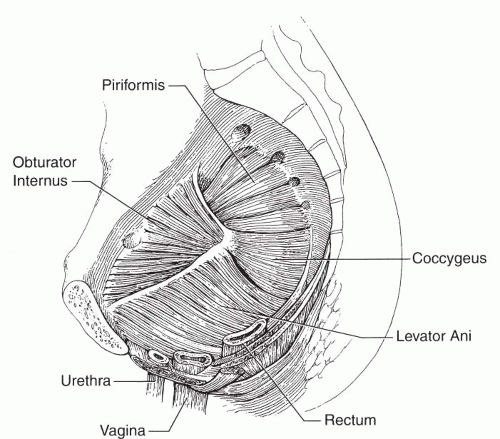

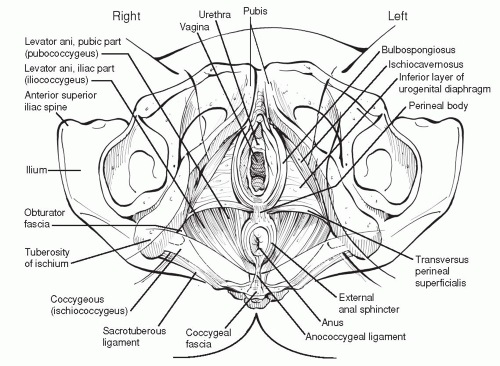

The pelvic floor serves a variety of functions. It is part of the support system for the pelvic organs, including the rectum, cervix, vagina, and bladder, helping to maintain normal anatomic relationships and actively participating in the storage function of these organs. The maintenance of some tone in the puborectalis is part of the anal continence mechanism,

specifically for solid stool. The puborectalis and external anal sphincter maintain a constant tone and relax at the time of defecation. The resting tone pulls the anorectal junction anteriorly to create a 90-degree angle between the rectal and anal canals. The musculature has a normal baseline tone eloquently described by Simmons (

14).

Muscle tension depends on the viscoelastic properties of the tissues in the muscle as well as the degree of activation of the contractile apparatus of the muscle. Muscle stiffness, meaning the resistance to movement with palpation, is a combination of these two properties. A variety of factors, such as radiation, can alter the elasticity of the tissues, leading to increased stiffness, absent of significant increases in contractility of the muscle fibers themselves. Electromyographic recording identifies only the electrogenic contraction of the muscle (i.e., the contraction elicited by electrical activity of the motor nerve and muscle cell). Pelvic floor musculature has a baseline resting tone defined as the viscoelastic stiffness in the absence of contractile activity (motor unit activity and/or contracture).

Defecation is initiated by voluntary relaxation of the puborectalis. The puborectalis also functions in the prevention of incontinence. With an effort to prevent involuntary loss of stool or gas, the anal canal constricts concentrically and pulls in, the latter a function of the puborectalis. A reflexive contraction of the pelvic floor during Valsalva helps to maintain the bladder neck in an intra-abdominal position, helping to maintain urinary continence.

The pelvic floor also has a role in sexual function. Contraction of the pelvic floor plays an important role in the sensation of the female orgasmic response.

Emotional Control of Pelvic Floor Function

One of the more fascinating aspects of pelvic floor function is the emotional motor control via the limbic system. The emotional motor system consists of a medial and a lateral component. The lateral component of the emotional motor system consists of a set of cell groups in the fore and midbrain, involved in a number of specific motor activities generally related to survival mechanisms, including defensive postures, vocalization, mating, and continence (

15). Holstege has demonstrated an output system in the feline in which the nucleus retroambiguus (NRA) projects to a distinct set of motoneuronal cell groups in the lumbosacral cord (

15). These cell groups are thought to participate in the posturing necessary for mating. In females, the strength of this NRA motoneuronal projection pattern appeared to depend strongly on the estrous cycles and was almost nine times as strong in the estrous as in the nonestrous females.

A common, well-known example of an emotional motor component is seen in the canine. Tail wagging and other tail movements have a strong emotional basis. With happiness or elation, the tail wags back and forth, a maneuver of the sacrococcygeus ventralis muscle. When threatened, the tail is brought between the legs, protecting the genitals, a function of the coccygeus muscles, much more developed in canine species. These are emotionally driven conditioned motor responses well documented in animal species.

As some of the more important functions of the pelvic floor involve continence of urine and stool, it is logical that some control of the pelvic floor should be activated in the fight-or-flight response (i.e., when threatened). This aspect of pelvic floor function was investigated in studies of vaginismus. Vaginismus is an involuntary contraction of the muscles of the urogenital diaphragm and perhaps the puborectalis muscle in response to attempted penetration. Van der Velde et al investigated pelvic floor muscular activity in women who were exposed to several different film segments, namely threatening, erotic, neutral, or sexually threatening (

16). They measured surface electromyographic activity during a baseline period of rest and during the film segments. Pelvic floor muscle activity was correlated with the threatening aspect of the film segments rather than the sexual content. In fact, the sexually threatening segment led to less pelvic floor activity than the threatening segment. They concluded that the increase in pelvic floor muscle activity was related to a generalized defense mechanism to a threatening situation rather to a sexually threatening situation. In addition, there was no difference between the vaginismistic subjects and the control subjects in response to the films, both groups tightening their pelvic floors similarly.

They subsequently repeated the study while measuring emotional responses to the film segments measured on a 7-point Likert scale, including enjoyment, fright, sexual arousal, disgust, relaxation, threat, and powerlessness. They concluded that the involuntary muscle contractions of vaginismus occur as an automatic defensive reaction in situations where conditioning of an emotion-symptom relationship had been established. Of the vaginismistic women, seven had a history of negative sexual experiences. This subgroup of women showed more muscle activity during the erotic segment. They concluded that in these women the

vaginismistic reactions may be explained by the fact that based on earlier experiences, erotic situations always have a threatening component (

17). This evidence gives an anatomic and functional basis to an emotional component of pelvic floor dysfunction and myalgia. With a history of exposure to a consistently threatening environment, pelvic floor dysfunction, tension, and myalgia can develop due to a prolonged sustained guarding posture. Over time, this leads to continued shortening of the muscles, overload, hypoxia, muscle dysfunction, and pain. This necessitates psychotherapy as a component of therapy to alleviate the threat, break the guarding posture, and enable the pelvic floor to exist in a more relaxed state. This again substantiates the notion of an interdisciplinary approach to chronic pain syndromes including physical therapy, psychotherapy, medical and possibly surgical interventions.