Pathology of the Uterus

Nilsa C. Ramirez

W. Dwayne Lawrence

The Normal Endometrium

The typical 28-day menstrual cycle can be divided into menstrual, proliferative, and secretory phases without a distinct demarcation between the end of one phase and the beginning of the next. The first day of menstrual bleeding is designated day 1 of the cycle. The menstrual phase lasts for an average of 4 days, during which a variable amount of tissue is sloughed and fluid is lost from the residual endometrial tissue; regeneration of the glands and surface epithelium has already begun before the midpoint of the menstrual phase. During the proliferative phase, which averages 10 days but can vary considerably in length from one individual to another and from one cycle to another in the same individual, the endometrial glands and stroma proliferate under the influence of rising levels of estrogens secreted by developing graafian follicles. Ovulation occurs typically on day 14 with the formation of a corpus luteum; progesterone secretion by the corpus luteum induces the onset of the secretory phase of the cycle. During this phase, the endometrium is primed for reception of the fertilized ovum. Glandular secretion is at its height from days 20 to 23, and progressive transformation of stromal cells into large predecidual cells dominates the last third of the secretory phase. If implantation does not occur, the corpus luteum degenerates, with progressively decreasing production of estrogens and progesterone. When these hormones have fallen to very low levels, the spiral arterioles of the endometrium undergo spasm and then dilation; the endometrial tissue undergoes degeneration, and menstruation begins. Evaluation of the architectural and cytologic variations in the glands, stroma, and spiral arterioles of the endometrium permits assessment of its phase of development.

Gross Examination

Hysteroscopic examination has demonstrated that menstruation usually begins in the cornual and fundal regions; in one study, sloughing was occasionally noted before the clinical onset of menstrual bleeding. Fragments of desquamated endometrial tissue appear gray-white, whereas the remaining mucosa is red and focally covered by white necrotic tissue. The late menstrual endometrium is thin and congested, with multiple punctate hemorrhages. Proliferative endometrium is pink-gray, smooth, and glistening; it increases progressively in height from 1 or 2 mm to 3 or 4 mm and occasionally is 6 or 7 mm just prior to ovulation. Secretory endometrium is yellow-white and glistening and may attain a thickness of 5 mm or more. About 5 days before the onset of menstruation or sometimes earlier in the cycle, the endometrium may have a polypoid appearance, simulating hyperplasia (Fig. 6.1). Around day 24 the endometrium begins to shrink, and by the onset of menstruation it is only one half to three quarters of its maximum height. This loss of tissue volume, resulting in a premenstrual thickness of about 2 mm, is caused principally by a loss of stroma fluid. If fertilization occurs, the endometrium continues to thicken. The ovum, which usually implants on day 20 of the cycle, may be visible on the endometrial surface as a slightly elevated red spot less than 1 mm in diameter.

The postmenopausal endometrium may be paper-thin if glandular atrophy with fibrosis of the stroma has occurred; however, if atrophy is less marked or irregular in its distributions, as often occurs during the first 10 or more years after the onset of menopause, the endometrium may be 1 or 2 mm thick. Thin-walled cystic glands are occasionally visible and are generally more numerous in elderly women.

Microscopic Examination

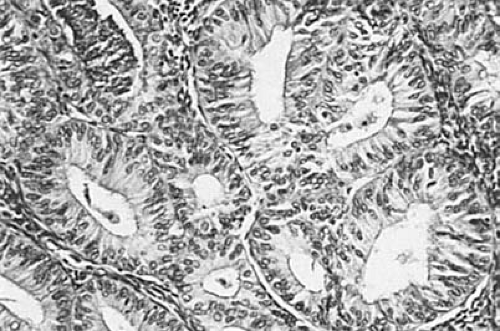

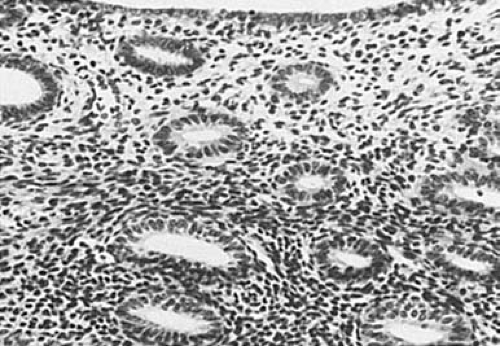

In the early proliferative phase, the glands are small, straight, and tubular and are lined by low columnar cells with basal nuclei, which may be slightly pseudostratified. Mitotic figures are uncommon. The stroma is composed of delicate stellate and spindle cells with sparse cytoplasm. As the endometrium continues to proliferate, mitotic activity increases in both the glands and the stroma and pseudostratification of the epithelial nuclei and enlargement and slight tortuosity of the glands are evident (Fig. 6.2).

In the early secretory phase, the first morphologic evidence of ovulation appears within 36 to 48 hours in the form of subnuclear vacuoles in the glandular epithelium. Mitotic activity and pseudostratification of nuclei disappear within approximately 3 days after ovulation as secretion begins to appear in the gland lumens; maximal glandular secretion and stromal edema are achieved between days 20 and 22 (6 to 8 days after ovulation). The beginning of the late secretory phase is heralded by prominence of the spiral arterioles,

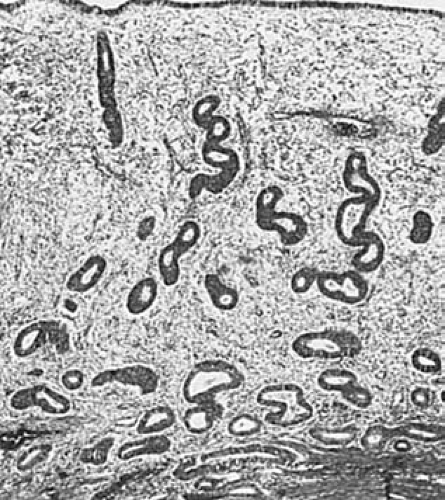

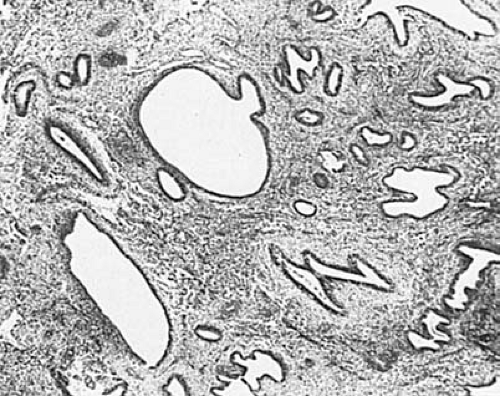

around which mitotic activity recommences in the endometrial stromal cells on day 23. The arterioles coil extensively, and the stromal cells acquire increasing amounts of pale cytoplasm, becoming predecidual cells. This change spreads throughout the upper part of the endometrium, and the glands assume a sawtooth configuration (Fig. 6.3). Subsequently, fluid escapes from the stroma and the endometrium decreases in thickness. Endometrial granular lymphocytes accumulate in increasing numbers as menstruation approaches. The latter cells (also known as endometrial granulocytes, metrial cell, K cells, and stromal granulocytes) were once considered to be derived from endometrial stroma, but further studies have demonstrated their origin from the large granular T-lymphocyte series. If implantation occurs, the endometrium becomes increasingly congested, the secretion and edema persist, and the predecidual cells become progressively larger to form decidual cells.

around which mitotic activity recommences in the endometrial stromal cells on day 23. The arterioles coil extensively, and the stromal cells acquire increasing amounts of pale cytoplasm, becoming predecidual cells. This change spreads throughout the upper part of the endometrium, and the glands assume a sawtooth configuration (Fig. 6.3). Subsequently, fluid escapes from the stroma and the endometrium decreases in thickness. Endometrial granular lymphocytes accumulate in increasing numbers as menstruation approaches. The latter cells (also known as endometrial granulocytes, metrial cell, K cells, and stromal granulocytes) were once considered to be derived from endometrial stroma, but further studies have demonstrated their origin from the large granular T-lymphocyte series. If implantation occurs, the endometrium becomes increasingly congested, the secretion and edema persist, and the predecidual cells become progressively larger to form decidual cells.

FIGURE 6.1 Secretory phase. The endometrium is yellow-white, glistening, and polypoid. Microscopic examination revealed this endometrium to be at day 19 of the cycle. |

FIGURE 6.2 Proliferative phase. The endometrium is relatively thin, with straight or slightly tortuous glands. (×64.) |

FIGURE 6.3 Secretory endometrium. The endometrium is thick, and its glands are tortuous with serrated border (×24.) |

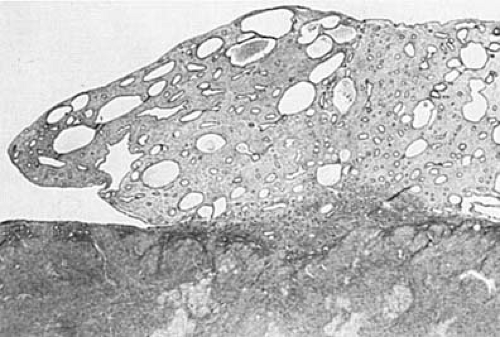

The postmenopausal endometrium varies from a relatively thick layer, with glands of varying sizes lined by mitotically inactive pseudostratified epithelium and abundant fibrous stroma, to a very thin layer containing small glands lying in a sparse component of fibrotic stroma (Fig. 6.4). The atrophic glands may be cystically dilated and lined by flattened epithelium. Varying combinations of these changes may be seen within individual endometria after the menopause. In general, the thicker endometria, which have been designated as showing inactive hyperplasia, are seen in the earlier postmenopausal years; simple atrophy (predominance of small atrophic glands) in later years; and cystic atrophy (predominance of cystic atrophic glands) in the most elderly age group.

Endometrial Hyperplasia

Diffuse hyperplasia of the endometrium results from a continuous exposure to estrogens unopposed by progesterone. This disorder may be encountered in women of a wide age

range in various clinical conditions. Women of reproductive age with anovulatory cycles, perimenopausal and postmenopausal women on estrogen therapy, obese women with a high rate of peripheral conversion of androgens to estrogens, and women of all ages with estrogen-producing ovarian tumors are among those subject to the development of endometrial hyperplasia. The drug tamoxifen, a nonsteroidal antiestrogenic compound that is used widely in the treatment of breast adenocarcinoma, has been implicated in some studies with the development of endometrial polyps, endometrial hyperplasia, and carcinoma.

range in various clinical conditions. Women of reproductive age with anovulatory cycles, perimenopausal and postmenopausal women on estrogen therapy, obese women with a high rate of peripheral conversion of androgens to estrogens, and women of all ages with estrogen-producing ovarian tumors are among those subject to the development of endometrial hyperplasia. The drug tamoxifen, a nonsteroidal antiestrogenic compound that is used widely in the treatment of breast adenocarcinoma, has been implicated in some studies with the development of endometrial polyps, endometrial hyperplasia, and carcinoma.

FIGURE 6.4 Atrophic endometrium. Small and inactive-appearing glands are set in a fibrotic stroma. (×64.) |

Focal hyperplasia, differing only in its extent from diffuse hyperplasia, is occasionally seen within an otherwise normal endometrium. The pathogenesis of this lesion is unclear; presumably, it results from a localized exaggerated response to estrogens or deficiency of progesterone receptors. Most examples of endometrial hyperplasia can be assigned to one of two major categories: simple hyperplasia and the complex forms. The latter have been known by various terms, among which are adenomatous hyperplasia, atypical hyperplasia, atypical adenomatous hyperplasia, architectural atypicality, cellular atypicality and carcinoma in situ. Simple hyperplasia, which includes cystic hyperplasia, is thought to have a very low malignant potential, whereas the more severe forms of complex hyperplasia are regarded as significantly precancerous.

The system of classification of endometrial hyperplasia proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Society of Gynecological Pathologists (ISGP) takes into consideration both architectural and cytologic features of the glands. It divides endometrial hyperplasia into four categories: simple hyperplasia, complex (adenomatous) hyperplasia, simple atypical hyperplasia, and complex atypical hyperplasia (adenomatous hyperplasia with atypia). The terms simple and complex refer to the architectural features of the hyperplastic glands, whereas the term atypia is used only if cytologic atypia is identified. Despite poor reproducibility, the use of this classification system has been widely accepted. Recent advances in the field of cytogenetics may assist in the development of a new classification system with better reproducibility and correlation with clinical outcome.

Gross Pathology

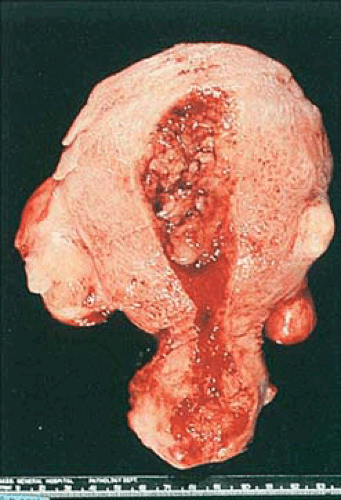

Although the hyperplastic endometrium may retain the glistening, mucoid, pink-gray appearance of the normal proliferative endometrium, it is usually thicker and is occasionally polypoid (Fig. 6.5). Small cysts may be visible, and dilated congested sinusoids may be seen just beneath the surface; although small red foci of hemorrhage and yellow foci of necrosis are sometimes seen, the latter finding should raise the suspicion of focal carcinoma.

Microscopic Pathology

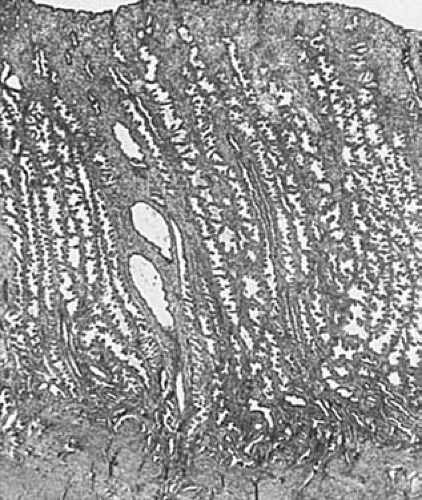

Simple hyperplasia typically has a characteristic Swiss cheese appearance on low-power magnification. Variably sized dilated glands, lined by flattened to pseudostratified columnar epithelium, are found either diffusely or focally on the background of a proliferative endometrium (Fig. 6.6). The stroma appears abundant and active with naked nuclei. Mitotic figures vary from few to numerous. If cytologic atypia is identified, the term simple atypical hyperplasia is used.

FIGURE 6.5 Endometrial hyperplasia. The endometrial cavity is occupied by thickened, irregularly polypoid, yellow-tan tissue without evidence of necrosis. |

Complex hyperplasia may be superimposed on simple hyperplasia but is also encountered in pure or almost pure form. This category includes various architectural abnormalities. If cytologic atypicality is also present, the term complex atypical hyperplasia is used.

In most cases, architectural and cellular abnormalities coexist to a parallel degree. The most common mild manifestation of the former is the presence of outpouchings from cystic glands, creating a so-called finger-in-glove pattern; the outpouchings may appear as small glands pinched off by stroma from the adjacent cystic glands. Despite varying degrees of glandular crowding, clearly recognizable stroma remains between the glands. With increasing severity of architectural atypia, epithelial stratification and glandular crowding become more prominent until only thin wisps of stroma separate thick-walled glands of distorted shapes (Fig. 6.7). Rarely, the lumens of the glands are obliterated focally by proliferation of the lining cells. Another form of complexity is the presence of papillae with fibrovascular stalks within dilated glands. Cytologic atypicality is characterized by nuclear rounding, hyperchromatism, pleomorphism, and loss of polarity. Mitotic activity is usually but not invariably increased, and the nucleoli may be enlarged and prominent.

FIGURE 6.6 Simple hyperplasia. Variably sized, generally rounded cystic glands lie in a cellular endometrial stroma. (×64.) |

Various metaplastic changes may be encountered in association with hyperplasia, including the acquisition of abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (eosinophilic metaplasia), the appearance of cilia on the cell surfaces (ciliated cell metaplasia), and squamous metaplasia (acanthosis), with the formation of “morules” of small, immature squamous cells, which may be centrally necrotic. These alterations do not of themselves indicate a premalignant state, but alert the pathologist to scrutinize closely the architectural and nuclear characteristics of the associated glandular epithelium, since metaplasia may occur in atypical hyperplasia as well as adenocarcinoma. Focal or diffuse glandular secretory changes may also be present.

In some laboratories the degree of complexity and cellular abnormalities within a specimen of endometrium are graded as mild, moderate, or severe, and the extent of the lesion within the entire specimen is determined. When cytologic and architectural features are indistinguishable from those of adenocarcinoma but the lesion forms a single focus of disseminated small foci without obvious invasion of the surrounding stroma, the designation carcinoma in situ has been used. The definition of carcinoma in situ of the endometrium is controversial, however, and most pathologists do not use the term, including for these lesions within the category of complex atypical hyperplasia.

Endometrial Polyps

Although endometrial polyps have been reported to occur in prepubertal girls, they are encountered almost always in older patients, particularly those in their fifth decade. These lesions may be asymptomatic or may be associated with abnormal uterine bleeding. Their frequency is increased in cases of endometrial carcinoma.

Gross Pathology

Endometrial polyps occur singly in about three fourths of cases. Although they may occur at any location within the endometrial cavity, they are found most often in the fundus, particularly in the cornual areas. They range from lesions a few millimeters in diameter to larger masses that occupy the entire endometrial cavity and simulate cancer. Some of them are sessile, whereas others have long, slender stalks (Figs. 6.8 and 6.9). Occasionally a large polyp protrudes through the external cervical os and very rarely through the introitus, mimicking procidentia. Most polyps are pink-gray to white with smooth, glistening surfaces, beneath which small cysts may be visible. Occasionally the entire polyp or only its tip is hemorrhagic or infarcted. It must be emphasized that various

lesions other than glandular polyps may have a polypoid configuration, including carcinoma, sarcomas, carcinosarcomas, adenosarcomas, leiomyomas, fragments of retained placenta (placental polyps), and even secretory endometrium.

lesions other than glandular polyps may have a polypoid configuration, including carcinoma, sarcomas, carcinosarcomas, adenosarcomas, leiomyomas, fragments of retained placenta (placental polyps), and even secretory endometrium.

Microscopic Pathology

The endometrial glands within polyps may have various appearances, which depend in part on the age and hormonal status of the patient. In women in the reproductive age group, they are often out of phase with those of the adjacent endometrium. Although they may be secretory during the luteal phase of the cycle, more typically they have a weakly proliferative pattern, and often they are cystically dilated. In postmenopausal patients, cystic glands lined by low cuboidal to flattened epithelium are most frequently encountered (Fig. 6.10). The stroma within polyps may resemble that of a proliferative endometrium but is often fibrotic. A consistent feature of a fully developed polyp is the presence of large, thick-walled blood vessels throughout its core. Occasionally, smooth muscle is present within the stroma of a polyp; if it is the predominant component, the term adenomyomatous polyp or polypoid adenomyoma is appropriate.

FIGURE 6.9 Endometrial polyp. An elongated slender polyp is attached to the fundus and extends to the internal cervical os. The surrounding endometrium appears flattened and atrophic. |

Various degrees of glandular atypicality and even carcinoma may be encountered within otherwise benign polyps. Serous and clear cell carcinomas have been reported to arise in endometrial polyps, as have malignant müllerian mixed tumors. When glandular atypicality, usually associated with acanthosis, occurs within an adenomyomatous polyp, the term atypical polypoid adenomyoma has been used. In a curettage specimen, this lesion is distinguishable from a low-grade adenocarcinoma or adenoacanthoma that has invaded the myometrium by the pattern of its smooth muscle, which resembles a leiomyoma and lacks the orientation of bundles seen in the normal myometrium.

Endometrial Carcinomas

Carcinoma of the endometrium occurs over a wide age range. Exceptional examples have been encountered in prepubertal girls, and fewer than 10% are seen in women of reproductive age; the great majority occurs in postmenopausal women. Just as in cases of endometrial hyperplasia, unopposed estrogenic stimulation has been shown

by numerous investigations to increase significantly the risk of endometrial carcinoma. Many of these tumors arise on a background of complex atypical hyperplasia, but some originate within an otherwise normal-appearing endometrium.

by numerous investigations to increase significantly the risk of endometrial carcinoma. Many of these tumors arise on a background of complex atypical hyperplasia, but some originate within an otherwise normal-appearing endometrium.

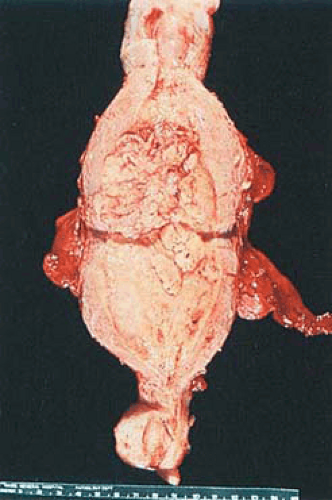

FIGURE 6.11 Endometrial adenocarcinoma. The endometrial cavity is occupied by a bulging, irregularly polypoid tumor with a pebbly surface. Opaque yellow foci are visible. |

Gross Pathology

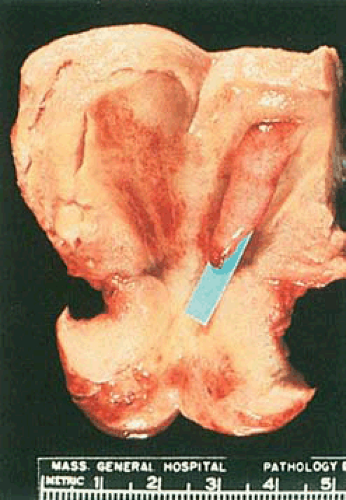

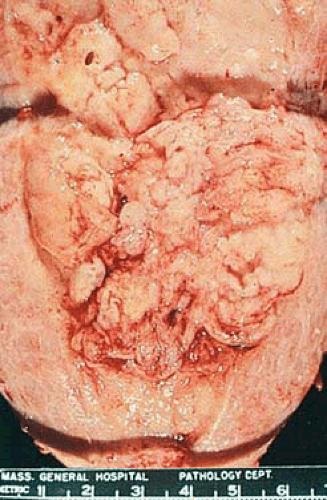

Endometrial carcinomas may be localized or involve the entire endometrium; when they are diffuse they typically terminate abruptly at the internal cervical os. Localized tumors may be polypoid and either sessile or pedunculated (Figs. 6.11 and 6.12). Although small carcinomas may be occult within a normal or hyperplastic endometrium or an endometrial polyp, the typical tumor is composed of irregularly heaped up tissue, which often has a pebbly or granular surface (Fig. 6.13). In contrast to the glistening, mucoid gray, elastic features of proliferative or hyperplastic endometrium, carcinomatous tissue appears opaque, dry, pale-yellow or white, and friable. Dark-yellow areas are often conspicuous as a result of necrosis of the accumulation of lipid-filled cells of stromal origin between the neoplastic glands. Hemorrhage and ulceration are common, particularly when the tumor is poorly differentiated, and abnormal vascular patterns may be seen on the surface of the tumor.

FIGURE 6.12 Endometrial adenocarcinoma. The anterior and posterior endometrial surfaces are occupied by yellow-tan, irregularly piled-up tumor, which terminates abruptly at the internal cervical os. |

FIGURE 6.13 Higher magnification of tumor in Fig. 6.12 shows the opaque, pale-yellow, irregularly polypoid surface of the tumor. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree